Leonora Carrington

The Old Maids 1947

Oil on board

582 x 738 mm

Robert and Lisa Sainsbury Collection, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts University of East Anglia

© Estate of Leonora Carrington / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2015.

Kati Horna

Wedding of Leonora Carrington and Chiki Weisz with their guests on the patio of the house of the Horna's, Tabasco Street 198, Colonio Roma, Mexico City, 1946

Photograph, 19.3 x 18.2 cm

© 2005 ANA MARIÀ NORAH HORNA Y FERNÁNDEZ. " (TODOS LOS DERECHOS RESERVADOS). Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery / Image supply Lund Humphries

A friendship is formed

In 1942, at the height of the Second World War, President Lazaro Cardenas opened the Mexican borders to welcome a number of Europe’s refugees. Artists, Leonora Carrington Remedios Varo and Kati Horna were amongst the many who found safe sactuary there. The three settled in the Colonia Roma, Mexico City, and soon became firm friends, alongside a group of other expatriate artists. Stefan van Raay, former director of Pallant House Gallery and curator of the 2010 exhibition Surreal Friends which was jointly mounted with Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich explains: ‘they created a surrogate family between themselves’. Within this close-knit community,the friendship of Carrington, Horna and Varo was particularly significant, and impacted strongly on each woman’s work.

The accompanying book Surreal Friends tells the individual stories of the three women and their relationship to one another.

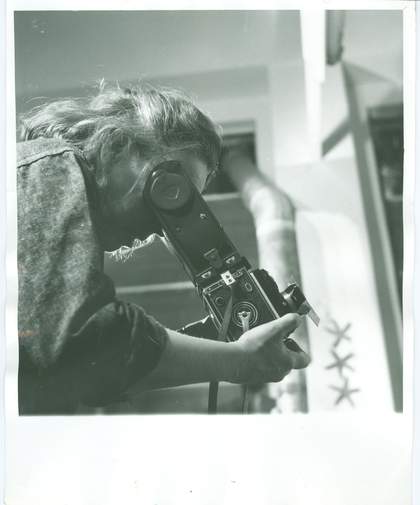

Kati Horna

Self Portrait, Mexico, n. d.

Gelatin silver print, 20.5 x 25.5 cm

© 2005 ANA MARIÀ NORAH HORNA Y FERNÁNDEZ. " (TODOS LOS DERECHOS RESERVADOS). Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery / Image supply Lund Humphries

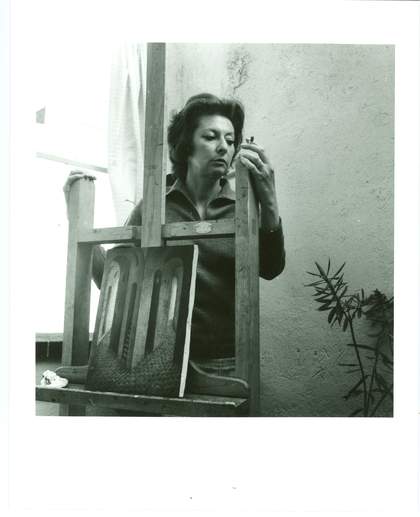

Kati Horna

Remedios Varo at her Easel, Mexico, 1963

Gelatin silver print, 22.3 x 25.2 cm

© 2005 ANA MARIÀ NORAH HORNA Y FERNÁNDEZ. " (TODOS LOS DERECHOS RESERVADOS). Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery / Image supply Lund Humphries

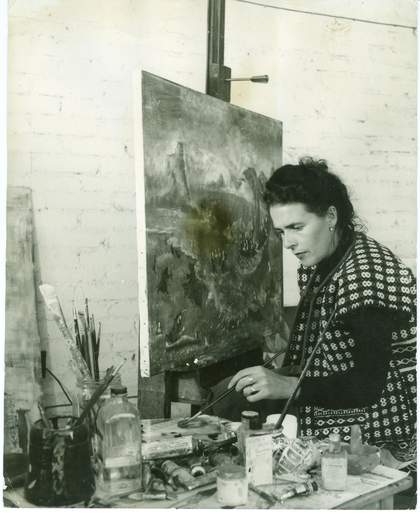

Kati Horna

Leonora Carrington at her Easel, Mexico, 1956

24.7 x 19.9 cm

© 2005 ANA MARIÀ NORAH HORNA Y FERNÁNDEZ. " (TODOS LOS DERECHOS RESERVADOS). Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery / Image supply Lund Humphries

Domestic at heart

The theme of domesticity is present throughout the work of all three artists. The familiar settings of kitchens, homes and gardens are made strange and otherworldly in Varo and Carrington’s paintings, yet their familiarity grounds them in real experience. When seen alongside Horna’s photographs, which capture her friends at the easel, we are given an insight into the unmeasured imagination which could take these ordinary surroundings into the realm of the uncanny. In Surreal Friends, Joanna Moorhead notes,‘Domesticity and motherhood, which sometimes prove the shackles to a woman’s creativity, seemed instead to liberate the potential of the Surreal Friends.’ Janet Kaplan wrote of the groups frequent “Surrealist games, practical jokes, elaborate costume parties and raucous story-telling into the night”. Likewise, it has been written that Carrington and Varo enjoyed cooking surrealist meals, or use herbs and philtres from the Mexican markets to try and make magic potions. Their playful imaginations permeated their quotidien, in work, as well as play. They provided companionship which could nurture their far-fetched fabrications; forming a collaboration which Teresa Arcq deems ‘unique in the history of art.’

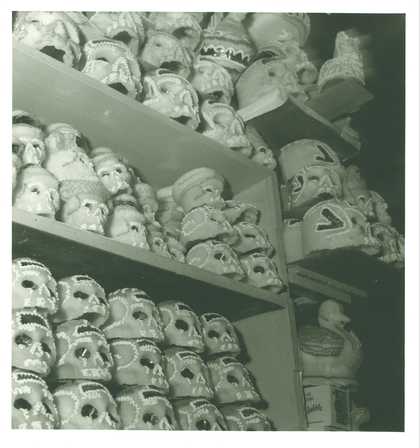

Kati Horna

Sugar Skulls, Series Sweets Market, Mexico, 1963

Gelatin silver print, 20.2 x 25.2 cm

© 2005 ANA MARIÀ NORAH HORNA Y FERNÁNDEZ. " (TODOS LOS DERECHOS RESERVADOS). Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery / Image supply Lund Humphries

Magic and the supernatural

The home became the site of powerful mediation as explained by Susan Aberth: “one of [Carrington’s] primary means of reclamation [of feminine agency]… was to equate the feminine domestic sphere with magical practices of diverse cultures. Thus the nursery, the kitchen, the kitchen garden, and so on, were transformed from sites of feminine drudgery and oppression into sites of contestation and power.” Varo and Carrington enjoyed studying alchemy, magic,Tarot and astrology, and these themes intricately lace their works together, as seen in Carrington’s Friday, 1978 or Night of the Eight, 1987, and Varo’s The Creation of the Birds, 1957.

Most of us, I hope, are now aware that women should not have to demand Rights. The Rights were there from the beginning; they must be Taken Back Again, including the Mysteries which were ours and which were violated, stolen or destroyed.

Here, Carrington not only refers to her belief in equality between the sexes, but also her investigation into the magic powers held by women in ancient pagan religion and traditions; Paintings such as Varo’s Witch Going to the Sabbath, 1957 and Carrington’s Three Women around the Table 1951, demonstrate the presence of these subjects within their lives, depicting mythical, or witch-like beings, holding potions or talismen. Likewise a letter by Varo to the founder of the modern witchcraft movement in England, Gerard Gardner, confirms their belief in these ideas: ‘I, Mrs Carrington and some other people have devoted ourselves to seeking out facts and data still preserved in isolated areas where true witchcraft is still practiced.’

Notions of the power of alchemy in witchcraft lead to a series of paintings which depict transformations from human to goddess, or animal. In many of their works female-like forms take on animal-like features. This was common in books on alchemy, where the alchemists would use animals to represent different stages of the chemical process. These paintings seem to convey a sense of elevated status and new found ability- as though in their roles as wives and mothers, far away from the disturbing experience of war, these women had discovered themselves.

Kati Horna

The Three Kings (José Horna, Chiki Weisz and Leonora Carrington) with Claudia Baker, Norah and Gaby, Mexico

12.8 x 17.8 cm

© 2005 ANA MARIÀ NORAH HORNA Y FERNÁNDEZ. " (TODOS LOS DERECHOS RESERVADOS). Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery / Image supply Lund Humphries

Capturing the context

Relating Horna’s work to that of Varo and Carrington may seem tenuous at first. It is in every way entirely different from theirs, not only in medium, but also in subject matter. Although she communicates elements of domesticity, the passion for alchemy and witchcraft is not quite so prevalent. Her work is often more grounded in documentary than imagination. Yet Horna’s practice spans many areas of photography, and certain images, such as Sugar Skulls, Series Sweets Market,Mexico, 1963, allude to the surrealist fascination for the otherworldly.

Despite obvious visual and thematic differences between Horna’s work and that of her friends, her inclusion in Surreal Friends positions her as an important contributor to the trio. Horna’s photographs contextualise and communicate the world beyond Carrington and Varo’s visualisation. We are given an insight into the experiences and emotions which shaped their paintings. Without this, their paintings would remain difficult to decode - so tightly woven are their mysteries and symbolic motifs. Stefan van Raay, notes: ‘Horna provides us with the visual proof of the subject.’ Therefore where Carrington and Varo enigmatically painted their reactions to the conflict in Europe, Horna supported this trauma with photographs of the frontline of the Spanish Civil War. When motherhood came into their lives, Carrington and Varo wove the home into their artworks, but Horna reinforces this with documentation of their families, whether her own daughter’s first day at school, or a nativity play with Carrington dressed up as one of the wise men. Horna’s documentation shows us the life behind the fantasies and is a key to understanding the cryptic works of her Surreal Friends.