Ian Berry

Zarina Bhimji 2003

© Ian Berry/Magnum

Zarina Bhimji was once invited to show her startlingly challenging art at a deeply conservative Islamic centre, and then threatened to withdraw unless she was allowed to include commentaries on the naked human body, male and female. This educative confrontation took place at the beautiful building opposite the Victoria & Albert Museum where the Ismaili mosque is used by worshippers each evening and dawn.

Bhimji won and the centre gained something immensely important, letting innovation and rebellion into the hallowed halls, with their ancestral geometric patterns and fountains paying eternal homage to the past. The walls did not crumble; faith was not polluted, and profoundly held values were nourished by being engaged with in the most audacious way.

Some Muslim communities are waking up to the fact that art, writing, science, new ideas and intellectual debate once used to define Islam in the world. When Europe was locked in superstition and a rejection of threatening ideas, Muslim scholars were devouring the work of Greek philosophers and creating vital, inquisitive cultures. In the past 50 years a dark age seems to have descended on the Islamic world, making too many Muslims disenchanted, suspicious and hopelessly nostalgic. Optimists detect a new renaissance slowly unfolding and Bhimji (who may or may not be a practising Muslim) is, in my view, partly located in this re-awakening.

Zarina Bhimji

Work in Progress 2001

Commissioned and coproduced by Zarina Bhimji and Documenta 11 © 2002 Zarina Bhimji

Zarina Bhimji

The Earth was coming off its hinges 1999–2001

Commissioned and co-produced by Zarina Bhimji and Documenta 11 © 2002 Zarina Bhimji

She is bold, daring, demanding. If she turns to Islamic history, it is with the vengeance of an activist. In the 1990s her Cleaning the Garden project featured the gardens and courtyards of the Alhambra, but this was to repudiate present-day European cultural storytellers who are hell-bent on excising the role and long presence of Islam from their land, and to remind post-Rushdie Muslims of what they once were.

Yet this dissident and sharp observer has given us, in Out of Blue, a film which is deteminedly conservative and questionably partial. This is one of Bhimji’s most personal expressions to date. As one of those forcibly dispossessed by Idi Amin exactly 30 years ago, she explores the unresolved pain and unanswered questions which still haunt many Ugandan Asians. Their lives before the expulsions hover restlessly, as they try to make sense of explanations which are only half true. This latest offering is a moving display of these half truths; effective yes, but not convincing in the end for those of us who know what happened and why.

Forced exile is a terrible thing. It is also one of the most powerful liberators of creativity. The dislocation sets free a range of dramas and stories without predictable ends – only questions, questions, and more questions. It lightens the burden of obligation to nationality and homeland while instilling a futile longing for both. It bestows on the lucky victims a profundity which you cannot learn anywhere. This intensity pulls you into Out of Blue, as the sounds circulate and tangle and as images emerge from the high, confident, affluent walls of Tate Britain. (Many of the shots are of walls of pain – of old decayed houses, of prisons with dried blood stuck in rivulets under the high bars, of the near-derelict airport at Entebbe.) Viewers are compelled to enter the inner rooms, the artist’s unquiet sensibility and the impossibility of closure.

Zarina Bhimji

Entebbe Airport

(still from Out of Blue) 2001

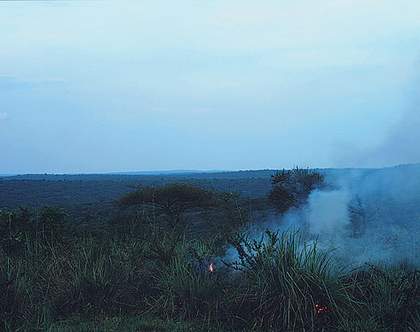

Out of Blue is a short tale of an imploded paradise (the conventional view taken by Asians of Uganda), and begins with the landscape which is still fresh for those of us who were driven from it. As the camera strokes its way softly across the beauty, three decades of distance vanish. In my autobiography No Place Like Home (incidentally also the title of a 1997 exhibition of Bhimji’s in Minneapolis), I wrote: ‘Uganda, with its moist and raging green everywhere, prodigious, boisterous flowers, trees and grasses and beautiful red earth. Utterly untamed.’ Bhimji’s initial, loving images capture this absolutely but inject a fragility which wasn’t there before, before the bloody history which saw a million black Ugandans slaughtered by its first two presidents between them.

Then comes a small fire in the grass. It gets larger; a cacophony of sounds invades the birdsong; ruthless Amin and his cronies threatening and ordering, sighs of bewilderment and sung recitals of pleading prayers from Asian victims and the greater, more gruesome pain of others going through a greater horror, those who were left behind to die or be tortured. The soundtrack kicks you in the stomach, raising panic without a name. And although it is a cliché, it works – the sun gets blighted by the thick black smoke which rises from the burnt terrain and charred hopes.

Bhimji is drawn to decayed buildings which speak eloquently. There are shots of rotting mansions once occupied by rich Asians (many of whom didn’t care enough that black Ugandans were left at the bottom of the economic pile, and did not address their own racisms). More moving are the lingering shots of modest little homes with tin roofs where ordinary Asians lived, spaces now freely occupied by spoilt chickens. There are mysterious dormitories with straw mats, precious plastic bags and cups and rows of guns. Are these barracks? Do we feel threatened or reassured that, without their guns, soldiers are pathetic and poor too?

The cells are also ambiguous. Black Africans occupy too slight a place in this work, yet they were the ones imprisoned and killed. Is this homage to them or is there some fiction to give a more tragic and cruel edge to our story? Hardly a dozen Asians ever died at the hands of the army in Uganda. But as a symbol of repression the shots scraping around the cell recreate the terror we all felt before we left. Perhaps this is the point. I went to Robben Island in Cape Town this year and visited the cells where Nelson Mandela, Ahmed Kathrada and other ANC prisoners were held. In South Africa, blacks and Asians fought together against injustice. In Uganda we did not. But Robben Island is a tourist trap now, and the testimonies soaked into the walls and hard floors have been silenced by too much talk from guides and politicians. In Out of Blue the silent screams of the imprisoned are left intact, and the integrity is staggering.

The sense of loss is evocative and everywhere – you can’t help but weep to see the dying graves of Asians left behind; you can’t carry your gravestones with you. Nobody to visit, to tend to these ancestors, our past. Here in Britain, our adopted country, the graves are cold, and our elders wor ry about this as they reach the end of their lives. Out of Blue animates memory, pain and loss beautifully, but there is much wallowing. We need the critical scalpel which Bhimji uses in her other work, more challenges to assumptions and some indication that we Asians were not perfect or indispensable, the country that we have left behind is not doomed forever. We may never forget Uganda but our lives are now rooted in the United Kingdom and indomitable black Ugandans are making their paradise bloom again. We no longer have claims on each other, and that is a new freedom.