Sam Francis had closer ties to Japan than any other major European or American artist of his generation: this, at least, was the assessment offered on the occasion of an important retrospective exhibition of his work in Japan in 1988.1 Francis spent a lot of time in the country and created numerous paintings and prints during frequent visits over many years. The largest single collection of his art was assembled in Japan, and two of his five marriages were to Japanese women. Moreover, many Japanese individuals expressed a remarkable degree of affection for the artist and their sentiments appear to have been warmly reciprocated by Francis.

Fig.1

Sam Francis

Around the Blues 1957, 1962–3

Oil paint and acrylic paint on canvas

2755 x 4875 x 50 mm

Tate T00634

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Japan did not really emerge as a factor in Francis’s life, however, until the artist was in his thirties, during the years bracketed by his work on Around the Blues (Tate T00634; fig.1), which was painted in 1957 and revised with significant additional brushwork around 1962–3. Francis first travelled to Japan after beginning this work in 1957, followed by a second visit in 1960–1, and it was during this period that he forged friendships with numerous leading figures in the Japanese art world. These years coincide with what came to be known as the ‘informel whirlwind’ (‘anforumeru senpū’), a wave of enthusiasm for gestural abstraction that swept the Japanese art world, triggered by the visits to Japan of three protagonists of the art informel movement in Paris: the art critic Michel Tapié, French painter Georges Mathieu, and Sam Francis. This essay provides an account of Francis’s increasing connections with Japan in the 1950s and early 1960s, and then considers the perspectives of four well-known figures in the Japanese art world who befriended him in this period: the painter Imai Toshimitsu, the art critic Tōno Yoshiaki, the poet and critic Ōoka Makoto, and the businessman and art collector Idemitsu Sazō. Each of them warmly supported Francis’s work in Japan, but their interpretations of his art in this period differed dramatically.

The art historian Peter Selz remarked that ‘Japan, with a tradition that considers art, above all, as meditative experience, almost immediately responded with sympathy to Francis’s work.’2 This view implies that Francis’s art struck a chord with an aesthetic disposition shared among Japanese people because of their presumed conformity with native tradition. For Selz, Francis was much like Japanese Zen Buddhist artists who, Selz believed, ‘understand better than any others the value of empty spaces’.3 Whether Zen-identified or not, a quality of spaciousness or a sense of void was indeed a theme addressed in much commentary on Francis’s work published in Japan as well as Europe and the United States. This aesthetic of emptiness emerged in Francis’s monochromatic all-over paintings of 1950–3: canvases covered with soft brushstrokes in light grey, or slightly yellow or pinkish tones producing an aqueous, cloudy effect. Many of his canvases from the mid-1950s onwards, including Around the Blues, are abloom with brushstrokes in blue and other colours, but as this painting’s title suggests, the unpainted white canvas showing ‘around’ the colours was of key significance. Furthermore, while the colours in Around the Blues seem unwilling to fully populate the large white bay in the centre-right portion of the canvas or its periphery, many of Francis’s works, such as the 1957 paintings Japan Line (private collection) and Honeyed (Marieluise Hessel Collection, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson), leave even more compositional real estate uninhabited.

Encouraged by the artist’s own statements, the space that Francis left untouched or relatively free of brushwork in his canvases stimulated much interpretation and speculative response.4 Like Selz, many were inclined to compare this quality of emptiness in Francis’s painting with Japanese and Asian theoretical and aesthetic concepts, such as nothingness (mu) in Zen Buddhism and the unpainted space (yohaku) in monochromatic ink painting. Japanese writers on Francis’s art occasionally corroborated the view that his sense of the void resonated with values in Japanese cultural history, but their responses also encompassed a wider range of interpretive directions that often contradicted this view. The four Japanese friends of Francis discussed here knew one another well and were all connected to the same network of Japanese elites, but the dramatically different ways that they defined, articulated and valued the void and other aspects of Francis’s work undercuts the notion that Japanese people were drawn to some underlying Japanese aesthetic in this American artist’s work. Before turning to these individuals’ views of Francis, however, I will trace the growth of Francis’s network of Japanese contacts in the 1950s.

Increasing contact with Japan

Francis moved to Paris, the international centre of the art world, in 1950 and here he soon began to meet visitors from Japan.5 In a 1951 letter to his father and stepmother, Francis reported,

The curator of the Japanese Museum in Tokio – who happens to be in Paris now seems to think that [my] paintings have a relationship to art of the Far East. Perhaps so – at any rate the influence is there mostly due to the large amount of Eastern Philosophy I have read. Let them have their fun.6

This phrasing suggests that at this point Francis did not take too seriously the view that his painting bore similarities to Asian art, but was willing to acknowledge a contemporary Asian viewer’s speculation about such relationships since he had read a lot about ‘Eastern Philosophy’. Among Francis’s readings in Asian thought, Georges Duthuit’s 1936 Chinese Mysticism and Modern Painting was probably of particular importance. In 1951 the sixty-year-old critic and art historian Duthuit befriended Francis, who was then twenty-eight and still a recent arrival in Paris, and Duthuit wrote several appreciative essays on Francis’s painting.7 According to the premise of Duthuit’s book, ‘analogies between Oriental and Western art have become constantly more numerous’ since the mid-nineteenth century, and Francis may have envisioned a place for his art in this larger convergence. Furthermore, he was no doubt intrigued by Duthuit’s characterisation of ‘the Chinese artist’ as a ‘clairvoyant’ who ‘seeks to discover the secret of the laws which seem to him to govern the forces of the universe’.8

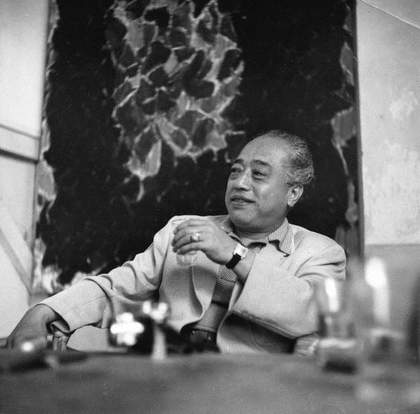

Fig.2

Teshigahara Sōfū visiting Sam Francis’s studio, Paris, c.1955

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

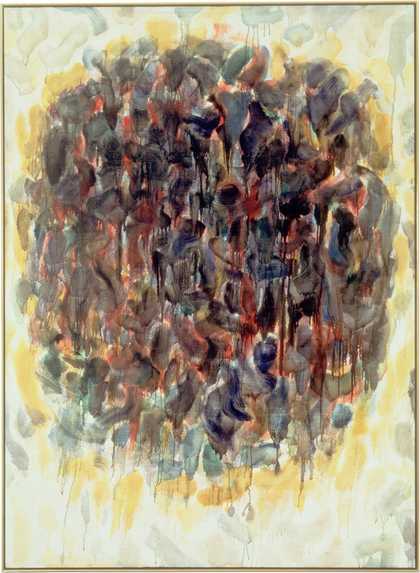

Meanwhile, Francis became acquainted with some of the many Japanese artists who had moved to Paris, as he himself did, in order to become part of what was often seen as the international centre of contemporary art. One Japanese artist who became a particularly close friend of Francis in Paris was Imai Toshimitsu, as will be discussed in more detail below. Imai’s sister-in-law was an instructor in ikebana (Japanese flower arranging), receiving her teaching licence from the Sōgetsu School of Ikebana in Tokyo, which was one of the largest and most progressive flower arranging schools in Japan.9 When Teshigahara Sōfū, who was the master of the Sōgetsu School as well as an artist and wealthy patron, came to Paris for his own exhibition in 1955, he was introduced to Imai, who in turn introduced Teshigahara to Francis. Teshigahara visited Francis’s studio accompanied by two of the most influential art critics in Japan, Takiguchi Shūzō and Tōno Yoshiaki (fig.2), and they would become stalwart supporters of Francis. In 1956 Teshigahara commissioned Francis to paint a mural for the headquarters of his ikebana school in Tokyo, and Francis was excited by this opportunity to travel to Japan for the first time: ‘have been offered a mural for a school in Japan in Sept. – will do all to get there.’10 Francis’s paintings could already be seen in Japan before the artist arrived, for example in Art of the World Today (Sekai konnichi bijutsu ten), a large exhibition that opened in Tokyo in November 1956.11 Francis was represented there by two works, including the 1953 canvas Untitled (fig.3), which features an oval-shaped cluster of predominantly grey brushstrokes surrounded by a yellow periphery. In his essay for the exhibition catalogue, Takiguchi wrote that informel painting ‘is to be especially noted among the overseas works because this movement represents the latest issues in today’s Paris art world’, and he identified Francis as one of a number of younger non-French artists in Paris who were ‘pushing Informel more boldly’ than their predecessors.12

Fig.3

Sam Francis

Untitled 1953

Private collection, Palm Beach, Florida

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Although European informel and American abstract expressionism started to have an impact in Japan in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the Art of the World Today exhibition presented a larger showing of new abstraction in Tokyo than ever before and constituted the first milestone for the informel whirlwind. Francis’s work could also be seen in another large exhibition in Tokyo in the spring of 1957, the Fourth International Art Exhibition of Japan (Dai-yon-kai Nihon Kokusai Bijutsu Ten), a show of 461 works by 356 artists from fourteen countries that travelled to nine cities in Japan. This exhibition was an eclectic mix of works by artists ranging from Marc Chagall to Diego Rivera, but Francis was one of five foreign artists who won an award, alongside eight Japanese artists, signalling the rise of informel in the Japanese art world.13

Fig.4

Francis painting Tokyo Mural in a studio borrowed from Teshigahara Sōfū in Mita, Tokyo, 1957

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Photo: François-René Roland, Paris

Fig.5

Installation view of the Sam Francis exhibition at the Tōyoko Department Store, Shibuya, Tokyo, October 1957

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Fig.6

Imai Toshimitsu (left) and Sam Francis (right) at their simultaneous solo exhibitions when they opened at a second venue, Kintetsu Department Store, Osaka, November 1957

After travelling for most of 1957 in New York, Mexico and California, Francis arrived in Tokyo in late September of that year to paint the mural commissioned by Teshigahara for the auditorium of the Sōgetsu building. This first visit to Japan lasted two and a half months, allowing time for meetings with numerous artists, dealers and writers who would become friends and associates during Francis’s periods of time working in Japan in subsequent decades. In addition to completing the eight-metre-long oil painting on canvas Tokyo Mural for installation in the Sōgetsu auditorium (fig.4), Francis also painted new works and added revisions to canvases he had started in New York and Paris. He did so in preparation for their inclusion in a solo exhibition that opened at the Tōyoko Department Store in the Shibuya district of Tokyo in October 1957 (fig.5). This was held side-by-side in the same venue with a solo exhibition of works by Imai Toshimitsu, who had by then returned to his home country, and the two artists spent much time together during Francis’s stay in Japan (fig.6).14

While he was in Japan Francis’s work appeared in yet another large international exhibition in Tokyo that highlighted informel works, the World Contemporary Art Exhibition (Sekai gendai geijutsu ten). The invitation to the opening of this exhibition billed it as an ‘international Informel festival organized to welcome [Michel] Tapié, [Georges] Mathieu, and Sam Francis’.15 After his departure from Japan in December 1957, Francis met a Japanese artist named Teruko Yokoi in New York, and married her in March 1959. In November 1960 Francis returned to Japan with the intention of purchasing a home for himself, Teruko and their newly born daughter. While painting a series of new works entitled Blue Balls for his solo exhibition at the Minami Gallery in Tokyo, however, he fell ill with tuberculosis and left Japan in January 1961. The exhibition opened in his absence in May, accompanied by a catalogue with texts by three Japanese writers, Takiguchi Shūzō, Ōoka Makoto and Tōno Yoshiaki.16

Fellow abstractionists: Francis and Imai

Fig.7

Imai Toshimitsu

Lava 1957

Oil on canvas

1140 x 1645 mm

Private collection

Francis first met Imai Toshimitsu in 1954, when the two young artists were fellow expatriates residing in Paris and pursuing abstract painting. They travelled in the same social circles in the Paris art world and became close friends, sharing the personal and professional triumphs and travails of artists beginning their careers amid conditions of material privation, as was nostalgically recalled by Imai in a tribute he wrote to Francis after the latter’s death in 1994.17 Imai had been painting large, semi-abstract figurative works – an approach similar to that of Parisian painters such as Jean-Michel Atlan – but soon gravitated towards the more unbounded, large-scale abstraction practised by Francis and other informel painters, such as Norman Bluhm and Jean-Paul Riopelle (see, for instance, Imai’s Lava 1957; fig.7).18

Nevertheless, despite Imai’s and Francis’s shared artistic proclivities and their common predicament as ambitious expatriate abstract painters in Paris, Imai was preoccupied with issues of Japanese cultural identity in ways that were foreign to Francis. Describing his aims in an essay for a Japanese art magazine in 1955, the year after he met Francis, Imai explained that he wished to move beyond the enclave of Japanese artists in Paris, but noted,

It is not all that easy to escape from the colony of one’s own countrymen and find oneself by entering the loneliness of Paris life … By possessing an international vision one begins to feel the problem of re-evaluating Japan more than ever. One must consciously train one’s sights on qualities of Japanese nature and tradition that are usually just understood unconsciously. These qualities must be grasped not merely with an Oriental and non-humanistic concept of nature, but with a modern consciousness and strong sense of global universality.19

Achieving this objective of combining Japanese tradition, modern consciousness and universality was a formidable mission in Imai’s view: ‘the future is hardly bright and affords more despair than hope’.20

Over the next two years, Imai arrived at the conviction that Western civilisation had come to an impasse and that Asian tradition could act as a promising resource. This situation posed an opportunity for Asian artists such as himself if they could overcome their postcolonial subjection:

Together with this collapse of Western rationalism, there is a world trend toward a deep interest in the Orient. Thus, we must abandon our past abject colonial mentality of servile devotion to the West, and actually create works that bring tradition to life through a contemporary awareness. We Oriental people must discover the unlimited space of void, temporality, color, and form within tradition and bring this traditional structure to life within contemporary works in a way that is structurally completely different from the West.21

In Imai’s thinking, which was aligned with the theories of historian and philosopher Oswald Spengler, ‘the West’ was a declining civilisation; it was in need of transfusions from ‘the Orient’ and Asian people were poised to supply these, but only if they could manifest themselves as ‘completely different’ from the West. Imai implied that the only hope for accomplishing this feat was by realising the potential of such qualities as ‘the unlimited space of the void’.

Francis may have served as a beacon for Imai in this ideological project due to his sympathy for Asian-associated ideals of the void, as visualised in the generous expanses of space in canvases like Around the Blues. On the eve of his first trip to Japan, Francis was lauded by a European critic for his ‘familiar[ity] with Eastern thought’ and as an individual who ‘knows how to employ the silence and the void of Oriental painting as artistic means of expression’.22 In Japan, too, even before he had travelled there, Francis was introduced as an artist who ‘grounded his work in the linkage of the individual to the universe in Oriental philosophy by bringing to life the white of the flat surface’.23 As an increasingly successful artist who was seen as a Western proponent of the ‘Oriental void’ in abstract painting, Francis may have legitimised Imai’s aspirations. He may also have offered hope that an appreciative reception awaited Imai’s own efforts at creating an idiom of abstraction with a more explicitly Asian authorship than Francis himself could provide. Dōmoto Hisao, another Japanese abstract painter residing in Paris at this time who was a mutual friend of Francis and Imai, articulated the logic of this reasoning; in 1956 Dōmoto praised the ‘fullness of the void’ in Francis’s painting, while expressing high hopes for Imai, whom he believed was poised to succeed in ‘greatly pushing the limits of Oriental potential in a way that only a Japanese person could accomplish’.24 In spring 1957 Imai advanced towards this aim with a sensational demonstration of Japanese tradition. During the course of his solo exhibition of large, densely painted abstractions at the Stadler Gallery in Paris, Imai staged a three-day Zen-themed event at the gallery for the Paris art world. It was held in a darkened room and featured a display of hanging scrolls, Noh masks and Japanese swords. While young Japanese women created flower arrangements and served tea, Imai recited poetry and brushed calligraphy amid the scent of incense, a slideshow of views of Buddhist sculpture and Japanese gardens, and a soundtrack of Gagaku music, Noh chanting and readings of Zen texts.25

A few months after this extraordinary display of exotic Japan in Paris, Imai returned to his home country, where Francis would soon join him for the two and a half months during which they were almost constant companions. The artists roomed together, painted together, exhibited together. According to Imai, they also partied together with Japanese women,26 initiating Francis into a homosocial conviviality with Japanese men that focused on erotic access to Japanese women in an environment structured by a rigid male-centred hierarchy.27 But beyond their personal friendship, the activities of Francis and Imai in Japan in 1957 were also a major component of the informel whirlwind. Francis arrived in Japan shortly after the exhibition and public painting demonstrations staged there by the French informel painter Georges Mathieu, and the art critic Michel Tapié was also promoting informel in Japan at this time.28 Among the Japanese individuals who encouraged the whirlwind, the artist, patron and leader of the Gutai group Yoshihara Jirō played a key role as an enthusiastic collaborator of Tapié. But Imai, too, had facilitated informel connections in Japan for Francis and others, and he would proudly claim that ‘the movement of Informel in Japan that I planned was called the “Informel Whirlwind” and had great influence on postwar Japanese art history’.29 The informel activities of Francis and the others were amplified by intensive coverage in the art press, including roundtable discussions, interviews, exhibition reviews and critical commentary. The influence of the gestural abstraction that characterised informel soon appeared in the work of countless artists in Japan including oil painters, artists working in the Japanese neo-traditional painting style known as ‘Nihonga’, as well as more radical artists in the neo-dada generation, not to mention ceramicists, calligraphers and ikebana artists.30

Tōno and the ‘death mask of contemporary painting’

Fig.8

Tōno Yoshiaki in Sam Francis’s Chelsea Hotel studio, New York, 1959

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

The young Tōno Yoshiaki, who would later come to be regarded as one of the three leading art critics of early post-war Japan (along with Nakahara Yūsuke and Hariu Ichirō), was among those who were deeply affected by the informel whirlwind. Tōno was also to become one of Francis’s most ardent supporters in Japan, and a prolific author of writings about the artist, including poetry, criticism and catalogue essays, as well as edited volumes (fig.8). In 1957, however, Tōno confessed that he was somewhat overwhelmed by the new informel painting: ‘Actually, the shock left me in such a daze that I cannot prevent myself from writing foolish praise.’31 Still, he believed that the paintings of Francis and Imai were among the best informel works he had seen, and distinguished their styles from one another by characterising Francis’s painting as ‘overflowing form’ in contrast to a ‘condensation ever inward’ in Imai’s work.32

Yet Tōno was sceptical of the implications of informel for Japanese art. He confronted Michel Tapié about the issue of the void in a roundtable discussion in Tokyo in 1957. Tōno may have already read Tapié’s brief statement for the brochure of Francis’s exhibition that was on view at the Tōyoko Department Store at this time. Here Tapié described the spatial quality that Francis had developed in his painting over the previous fifteen years in California and Paris as ‘nearly the same as that of mu, the mu that conceals vast contents within’, and anticipated great accomplishments from his current work in Japan:

Japan is a nation that teaches what can be called the creative indivisibility of Zen philosophy. It is a nation where artists have put more effort into expressing mu than any other country in the world. Here [Francis’s] painting will soar straight up to the summit without compromising his intention and invite us to a new ritual by means of mu.33

Fig.9

Roundtable discussion, Tokyo, October 1957, with (clockwise from left) Haga Tōru, Michel Tapié, Hariu Ichirō, Ōoka Makoto, Tōno Yoshiaki and Nakahara Yūsuke

Published in ‘Zadankai: Misheru Tapie-shi o kakonde’ (‘Gathering with Mr. Michel Tapié’), Mizue, no.627, October 1957, p.23

The tone of this prediction, which greatly exceeds that of Francis’s own statements, may have seemed presumptuous. At the 1957 roundtable discussion with Tapié and several Japanese art critics (fig.9), Tōno laid out Japanese perspectives of the void and informel, and put his question to the French critic as follows:

In your thinking Mr. Tapié, Informel is strongly generalized, while it seems to me that the resistance of Oriental otherness has not been considered. For example, in comparison to concepts such as nothingness (mu) [in Japanese Buddhist thought], Informel is rather more of a presence than a nothingness … Yet, for us, that sort of Oriental nothingness does not actually appear except in an extremely conventional kind of form. In order to break through this sort of convention, we must pass temporarily through a Western approach. Though I’m not entirely sure yet, in this situation, when we create a really new art, I would hope to see something different come about. In this sort of confrontation with something Oriental, didn’t you feel some true otherness?34

In this statement Tōno seems to invite the critic, newly arrived from Paris, to speculate on the potential of Japanese protagonists to play a distinctive role in the transnational arena of informel. Tapié’s response, however, was clearly not satisfactory to Tōno. Tapié replied that coming to Japan he had ‘absolutely no feeling of being in a foreign country, because for a long time I have habitually been thinking in terms of espace vide (empty space)’.35 While Tōno might have imagined that the concept and appearance of the Oriental void could hold special potential for Japanese expression by painters like Imai, Tapié now claimed that he was already long familiar with such ideas through earlier European and American artist-producers of Asian-inflected abstraction, such as the painters Henri Michaux and Mark Tobey.36 Although he does not mention Sam Francis again here, we have already seen that Tapié similarly admired Francis as a Euro-American master of the Oriental void.

Fig.10

Sam Francis

Blue Balls I 1960

Private collection

© Sam Francis Foundation, California/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Tōno, however, was less inclined to associate the white ground in Francis’s painting with Oriental philosophy. Perhaps this is not surprising because his comments to Tapié suggest his hope that the Oriental void could provide an opportunity for Japanese artists to ‘create a really new art’. In 1961, after the informel whirlwind had subsided somewhat, and after Tōno had spent time with Francis in New York, Paris and Tokyo, the critic published an essay titled ‘Sam Francis, or After the Death Mask’.37 This essay contemplates the significance of Francis’s abstraction, including the aforementioned series Blue Balls, a title the artist is said to have adopted at Tōno’s suggestion. While numerous masses of blue and other colours cluster and coagulate into areas of heavy density in Around the Blues, large, loosely painted orbs of liquid blue float and ooze in great expanses of white space in the later series (see, for instance, Blue Balls I 1960; fig.10). Writing in the highly subjective and poetic mode of response to Francis’s painting that was common among French and, increasingly, among Japanese admirers of Francis’s work, the allusions Tōno derived from his painting were decidedly European, although they ranged widely from the Byzantine mosaics of Ravenna to writer and artist Jean Cocteau’s protégé, the novelist Raymond Radiquet. The title motif of Tōno’s essay, the ‘death mask’, designates a bleak modern sort of nothingness that, for Tōno, was evoked by the blank white in Francis’s painting:

Perhaps there is only one face permitted in our times, the death mask. All present-day forms of expression are wiped away. The human face is made into one unmoving mass of matter, refusing all potential faces and hiding all actual faces. Facial expression is but an optimism that must always feel the scorn of the death mask at its back. It seems to me that Francis’s white is the death mask of contemporary painting.38

While death and despair are the overriding tone of this essay, in his treatment of Francis’s white Tōno does allude to the life-giving plenitude associated with nothingness in non-dualistic Buddhist thought. ‘If you call this nothingness (kyomu),’ he writes, ‘what a strange nothingness it is. It is not a nothingness that just means death alone, or life alone, or a simple denial or affirmation; rather it is nothingness like a deep body of mist. It is nothingness in which the creative and the destructive are absolutely the same.’39

Ōoka and ‘The Silence of America’

Since first meeting Francis, Tōno’s attention was increasingly drawn to the work of younger and more radical New York artists such as pop artists Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, and his writing about them would have a decisive impact on the Japanese avant-garde of the 1960s. In pursuit of this research, Tōno resided in New York in 1959, borrowing Francis’s spacious studio and apartment while Francis was in Paris. Tōno sent a series of letters from New York to Japan, to his friend Ōoka Makoto, the third protagonist among Francis’s Japanese friends considered here. At this point, the twenty-eight-year-old Ōoka was just beginning what would become a successful career as a poet, newspaper columnist and occasional art critic. He would also go on to produce several important publications on Sam Francis.

Ōoka was deeply moved by Tōno’s letters from New York, and in August 1959 he penned a brief essay characterising American culture based partly on Tōno’s descriptions.40 Titled ‘The Silence of America’ (‘Amerika no chinmoku’), Ōoka’s essay positions the sense of emptiness in Francis’s abstraction as one manifestation of a ‘silence’ that he regarded as a uniquely American cultural phenomenon. He notes that despite the fact that New York City is obviously an active metropolis, Tōno had characterised the city’s streets as ‘extremely dull’ and reported that its buildings looked like ‘corpses’ from the windows of Francis’s studio. Ōoka then associates Tōno’s impression of New York City with his own response to the canvases of Francis and other abstract expressionists, where he senses a ‘silence of outer space, a boundless spreading space’. Ōoka traces this thread through the work of John Cage, the composer of 4'33" (1952), a piece of music consisting of silence, in which the pianist refrains from producing any sound at the keyboard. Cage’s silence is then linked to an attitude of ‘indifference’ in the art of Johns and Rauschenberg, and to ‘the silence of a strange blackness’ in a poem by Wallace Stevens that resonates further, in Ōoka’s view, with the ‘silence of the desert space of the American continent’. Thus, for this Japanese poet, the sense of emptiness in Francis’s work was deeply rooted in an exotic American context.

However, a few years later, the same Blue Balls series painted by Francis in Tokyo that had moved Tōno to contemplate the ‘death mask of contemporary painting’ now prompted Ōoka to rethink his American identification of Francis’s abstraction. Ōoka’s poem ‘Sam’s Blue’ that appeared in the catalogue of Sam Francis Blue Balls, the exhibition in which these works were first shown in 1961, starts with the lines,

Of the blue of Sam I know nothing

except it is filled

with round bright nothingness

winds moving around

the nonexistent shores41

‘American silence’ has vanished, but although these works were painted in Japan, Ōoka does not offer any Japanese interpretation either. It would seem that the ‘round bright nothingness’ transcends all geographic and cultural identification.

Collecting the void: Idemitsu Sazō

While residing in Francis’s New York apartment in 1959, Tōno hosted a visitor from Japan who would interpret the sense of emptiness in Francis’s painting in a dramatically different way to either Tōno or Ōoka. Tōno was accompanied in New York by his wife, Idemitsu Takako, and the visitor in question was Takako’s father, Idemitsu Sazō, the founder and president of Idemitsu Kosan, the second largest oil corporation in Japan. While visiting, Idemitsu Sazō encountered Francis’s painting for the first time and became so enamoured with one canvas, White Line 1959, that he asked Tōno to purchase it for his art collection. This first acquisition of a Francis painting by Idemitsu was the beginning of what would become the largest collection of Francis’s work in the world: the 160 works owned by the Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Tokyo. In 1959, however, modernist abstraction was still a relatively new area for the seventy-four-year-old Idemitsu, whose collection at that time primarily consisted of works by the eighteenth-century Zen monk and painter Sengai Gibon, as well as other Japanese and Chinese antiquities.

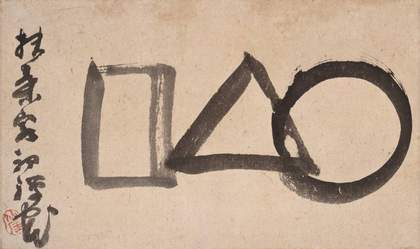

Fig.11

Sengai Gibon

The Universe 1819–28

Ink on paper

284 x 481 mm

Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Tokyo

Idemitsu regarded Francis as an artist who resembled Sengai because of his grasp of the significance of the unpainted ground (see, for instance, Sengai’s The Universe; fig.11). The wealthy businessman explained his views of Francis in some detail in a 1959 essay (perhaps the edited transcript of oral remarks) titled ‘Sam Francis and Sengai, the “Mu” of Contemporary Painting in Conversation with Zen Painting’.42 For Idemitsu, while oil painting of the West is ‘all covered up by system and logic and so on, such that there is no opening for human beings to enter’, the white ground (hakuchi) in Francis’s painting ‘admits humans’.43 In this regard, Francis’s work resembles Japanese painting, such as the brush and ink works by Sengai that Idemitsu had collected in very high numbers since his youth. Idemitsu’s comparison is premised on an East/West binary: ‘In the thinking of Western people, yū (existence) is something that exists and mu (nothingness) does not. However, in the Orient there is mu thought.’44

Francis was not the only contemporary Westerner whom Idemitsu believed had breached this divide. In language that he seems to have carried over from his oil business in order to identify the potential of ‘nothingness’ to be marketed as a commodity, Idemitsu notes that ‘it is in the present day that the property (zaisan) of mu has come into demand in foreign countries’. Still, although he had observed mu emerging in the work of various French painters, he believed that most abstract painters seem caught up in ‘frivolous arguments based on logic’. ‘With Sam Francis’s painting,’ however, ‘it’s not a matter of an argument, it’s just mu.’45 Idemitsu closes his essay with comments about his plans for creating the private museum that would be established in 1966 as the Idemitsu Museum of Arts. This was not to be a conventional museum dictated by the systematic approach of an art historian, but rather a place that would ‘simply display Sengai and Sam Francis together as collected by one eye like mine’.46 An imagined fellowship between Francis and Sengai was to be the cornerstone of the museum, and the collector implied that he hoped this bond could contribute to bridging the cultural gap between Japanese and Western people.

Entering the void: Participation and exchange

Francis and his Japanese interlocutors can be situated in a vast transnational zone of interactivity between modernist abstract art and various contemporary and historic Asian perspectives.47 Throughout the twentieth century, painters, sculptors and calligraphers, as well as art critics, journalists, scholars and dealers, in North America, Europe and Asia were intrigued by the idea that Euro-American abstraction could be universalised through the creative exploration of affinities or areas of overlap with Asian philosophy, tradition and visual culture. This interactivity, however, was accompanied by an abiding sense that authentic artistic expression required a continuity between one’s national or racial identity and the cultural signifiers of one’s art. Thus, the experimental hybridisation of properties associated with Asia – such as the metaphysics of the void or brush and ink calligraphy – with Euro-American developments in abstract art was fraught with anxieties about cultural border-crossing.

At the same time, as art historian Ming Tiampo has demonstrated in her study of the Gutai group, Japanese proponents of abstract art identified themselves as active producers of the most advanced art of their day. Their efforts to attain status on the world stage of abstract art, however, were often caught in a double bind: if their work looked too similar to models associated with Paris or New York, they were likely to be castigated as ‘derivative’, but if their work seemed too different from such models it was likely to be rejected because it was not recognisable as art.48 Sam Francis served as a particularly productive touchstone for his Japanese friends in this process of weighing up viable measures of sameness and difference. Yet the contrasting and conflicting views of Francis’s work that his friends and supporters voiced demonstrate that these negotiations were highly unstable and produced diverging responses rather than consensus. It would be highly misleading to claim that ‘Japan’ as a whole responded uniformly to Francis’s work.

The above account of Japanese individuals’ views of Francis in the period that he painted Around the Blues is by no means exhaustive. Although mentioned only in passing here, such figures as the art critic and poet Takiguchi Shūzō and the patron and ikebana master Teshigahara Sōfū were also crucial to the formation of Francis’s relationship to Japan. Nonetheless, the four individuals discussed provide a vivid sense of the range of views about Francis’s work that emerged in Japan in this period. The painter Imai Toshimitsu found legitimisation in Francis’s interest in the Oriental void for his pursuit of more overtly Asian values in his own abstraction. The critic Tōno Yoshiaki, perhaps wishing to reserve a distinctly Japanese and Asian foothold in the transnational informel movement, identified Francis’s white ground as a more European phenomenon characterised by a bleak nihilistic sense of nothingness. Tōno’s friend, the poet Ōoka Makoto, however, discovered an American sensibility in Francis’s painting from the late 1950s and early 1960s, a silence that characterised a wide range of contemporary American cultural expression and that resonated with the country’s urban and rural environment. This Americanness vanished, however, into transcendent nothingness when Ōoka contemplated paintings Francis created later in Japan. Among these four interlocutors, the industrialist Idemitsu Sazō offered the most full-throated statement of the view that Francis’s art resonated profoundly with Japanese cultural identity, with his belief that the white ground in Francis’s work corresponded to the mu of Zen Buddhism and the unpainted passages in works by Sengai.

These four perspectives on Francis’s painting would continue to evolve and respond to new developments in the artist’s work. But during the period of these figures’ first encounters with Francis’s work in the 1950s and early 1960s their views are striking for the great disparities in what they valued in his abstraction. Their disagreement about the void in his work counters the assumption that it reflects a Japanese racial, cultural or aesthetic predisposition to empty space. It also runs against the idea that this predisposition is the reason Francis forged closer ties to Japan than other foreign contemporary artists.

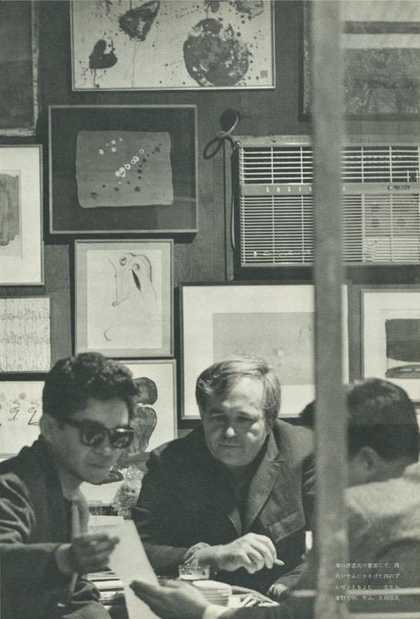

Fig.12

Futagawa Yukio

Photograph taken in Takiguchi Shūzō’s study, 1964, with (from left) Tōno Yoshiaki, Sam Francis and Ōoka Makoto, while Takiguchi (not visible in the photograph) reads a poem dedicated to Francis

Published in ‘Photo Interview: Sam Francis’, Mizue, no.712, June 1964, p.74

What, then, explains the unique status of Francis in Japan? I propose that the impression of empty space associated with his painting operated like a vessel that generously accommodated a wide variety of creative interpretations. Perhaps more than other types of spatiality constructed in abstract painting, the void was one that admitted participation and creativity. This void – for example, the oceanic white that sits ‘around the blues’ in Tate’s painting – was an arena conducive to productive exchanges and interactions among viewers and critics. In 1964 the art magazine Mizue published a ‘photo interview’ of Francis that showed the artist during his recent visit to Japan. He appears to be utterly at home with Tōno, Ōoka and other Japanese friends, enjoying poetry with them in one image and playing baseball in another (fig.12).49 The photographs were accompanied by a poem by Francis titled ‘Toward Disappearance’ that seems to have been addressed to his Japanese friends on the eve of his departure from Japan. The poem ends with thoughts that, if applied to the void, suggest a kind of emptiness that rejects the bleakness of Tōno’s ‘death mask’ and at the same time evades exclusive cultural identification, whether Oriental, European or American. Rather, the void stands as a kind of open potentiality:

Coexistent = coeternal?

Tokyo I am leaving

so enjoy yourselves / self

making love.