When African American artist Norman Lewis exhibited Cathedral 1950 in the United States pavilion at the 1956 Venice Biennale as part of the exhibition American Artists Paint the City, he introduced Harlem’s architecture and the vivid formal vocabulary of New York’s abstract expressionist artists to a largely European public that was thirsty for new visual material.1 The presence of Cathedral in Venice took place in the context of several exhibitions featuring works by abstract expressionist artists between the first post-war Biennale in 1948 and Mark Tobey’s winning of the highest prize at the Biennale, the Leone d’oro (Golden Lion), in 1958. Among the various vectors of dissemination for abstract expressionism, the Venice Biennale offered an unparalleled opportunity for New York School painters to present their work in Europe in the 1950s. As an alternative to the public museum and commercial art gallery, the Biennale’s national pavilion format occupied a unique role in the display of abstract expressionism during this decade.

A new framework for modern art was emerging in which the international landscape of modern art practice collided with the large-scale exhibition. It was in this changing climate that the Venice Biennale took on increasing international significance and institutional impact in the 1950s. This decade marked a time in which the Biennale directly intersected with other exhibition paradigms and sectors of the art world including the public museum, the emerging figure of the independent curator, the commercial gallery system and the art fair. These coeval developments shaped the Biennale just as much as the Biennale in turn informed contemporaneous venues and modes for presenting art. Elsewhere in the world, established and emerging institutions alike looked to the Venetian paradigm, as the internationally recognised large-scale exhibition became a sought-after platform.

This essay explores the role of the Venice Biennale’s national pavilion structure as an international format at the onset of the 1950s, the relationship between the Biennale and the museum, and the role of abstract expressionism and the United States pavilion in the broader Euro-American context. Woven into this is a consideration of Lewis’s Cathedral at the 1956 Venice Biennale with regard to the large-scale global biennial as an exhibition platform in the 1950s. Events such as Peggy Guggenheim’s presentation of her collection in the 1948 Greek pavilion, the Museum of Modern Art’s acquisition of the United States pavilion in 1953, Katharine Kuh’s 1956 Biennale show American Artists Paint the City and the 1958–9 European tour of the exhibition The New American Painting were pivotal moments in shaping the course of the American presence in Venice in the 1950s. In examining these events and others, this study seeks to unpack the history and significance of the Biennale vis-à-vis large-scale exhibitions elsewhere in the world at the time and to assess the outcome of these factors by the end of the decade.

Fig.1

Norman Lewis

Migrating Birds 1953

Collection of Halley K. Harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld

© Estate of Norman W. Lewis; courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

When Cathedral was on view in the United States pavilion in 1956, it was hardly the first or last time that Norman Lewis would exhibit his work within the context of perennial group exhibitions. The large-scale perennial exhibition played a significant role in the domestic and international reception of Lewis’s work in the 1950s. In fact, the year prior to his participation in the Biennale, Lewis had won the Popularity Prize for his painting Migrating Birds 1953 (fig.1) at the 1955 Pittsburgh International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting, or Carnegie International.2 Lewis would participate in the Carnegie International again in 1958.3 The perennial exhibition therefore provided an important platform in the 1950s on either side of the Atlantic for the reception and display of works by Lewis and other artists as well as legitimised the nomination of his work’s inclusion in the Venice Biennale of 1956.

Abstract expressionism and the US pavilion: National territory and the museum alternative

At the onset of the 1950s, works by Lewis had been included in several landmark abstract expressionist exhibitions on the domestic front, notably in the 1951 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art titled Contemporary Painting in the United States and that same year in Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. While these nation-based and medium-specific exhibitions signalled the beginning of a new era of painting, they were also part of a broader nationalism sweeping the country. Geopolitical, socioeconomic and institutional interests mediated the movement of American art to Venice beginning in 1948. Over the course of the 1950s, various iterations of the US pavilion exhibitions served as part of a network of temporary exhibitions that sought to ‘export’ a certain national identity and to implement the contemporary political agenda.4 For example, after showing his work at the 1954 Venice Biennale, sculptor David Smith subsequently travelled as a delegate to the UNESCO First International Congress of Plastic Arts. MoMA purchased the US pavilion in 1953, and in the years that followed MoMA’s International Council played a major role in presenting American art as such.5 The presentation of abstract expressionism in Venice secured its international status and attempted to mark this brand of abstraction as a distinctly American enterprise.

Outside of Venice, the exhibition per se became a direct instrument of foreign policy: title, location and participants were paramount, and the broader framing of American art teetered on near obsession by politicians and foreign policy officials alike. Nationalism became a significant part of post-war cultural policy in the wake of the Truman Doctrine in 1947.6 In Myth-Making: Abstract Expressionist Painting from the United States, art historian David Craven considers this critical period by calling attention to several landmark exhibitions, including Twelve Modern American Painters and Sculptors, which was sponsored by MoMA’s International Council and travelled to Zürich, Düsseldorf, Stockholm, Helsinki and Oslo in 1953.7 In 1956 US Congressman George Dondero declared modern art ‘un-American’ in a speech called ‘Communism Under the Guise of Cultural Freedom is Strangling American Art’ and in so doing advocated for a censorship of art.8 The same year, the American government suppressed the Sport in Art exhibition organised by the American Federation of Art to coincide with the Olympic Games and another exhibition organised by the College Art Association because it included works by Pablo Picasso, who was a critic of the saturation bombing of Korea in the early 1950s.9 These exhibitions elsewhere in Europe demonstrate the extent to which the gallery space became a battleground for visual politics, as a nationalist imperative meticulously distilled and re-qualified American art to fit the exported political agenda.

Throughout the 1950s the Venice Biennale’s national pavilion format proved distinct amid the rapidly expanding commercial market for contemporary art in Paris, Milan and especially New York in the late 1940s and the 1950s.10 At the same time, the line between the national pavilion and the art market was often blurred. It was in this climate of an enthusiastic dealer-collector system and the emerging art fair that the Venice Biennale straddled a nebulous boundary between the commercial and the public. The United States pavilion at the Venice Biennale therefore provided a platform for exhibiting abstract expressionism that was neither museum nor gallery, while at the same time catered to the public in a way that no other domestic institution could offer at the time.

Among the multiple post-war venues that contributed to the canonisation of abstract expressionism, the public museum performed a crucial role. MoMA played a key part in doing so in New York and even in its activities abroad. Moreover, the 1950s witnessed the birth of new museums devoted to modern and contemporary art not only in the United States, but also in Europe. Examples include the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, which opened in 1947 but expanded substantially in the early 1950s, the separation of London’s Tate Gallery from the National Gallery in 1955, and the establishment of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1958. However, in Italy such museum growth did not occur. In its place, the Venice Biennale began to share duties normally assigned to these then-burgeoning museums and to involve leading art historians in the organisation of exhibitions, a development that occurred in tandem with the emergence of the curator as a trans-venue operative. Rodolfo Palluchini, the Secretary General of the 1948 Biennale, included art historical exhibitions and notable art historians themselves for the first time. Both the historical survey and the solo artist’s retrospective characterised art historical exhibitions such as Roberto Longhi’s exhibition on French Impressionism and Renato Guttuso’s Picasso retrospective, both in 1948. Furthermore, Giulio Carlo Argan, renowned art historian and future founder of Italy’s National Cultural Ministry, organised the display of Peggy Guggenheim’s collection in the Greek pavilion in 1948. This broad exhibition showcased 136 works by 73 artists, one of which was Jackson Pollock, constituting his first introduction to a European audience. At the same time it first showed signs of assuming museum roles, the Biennale was characterised by a lack of institutional mediation abroad: Biennale exhibitions were organised directly by countries, providing an alternative narrative to those of local museums.

The combined broader scope of the exhibition, a newfound interest in historical content and an increasing visibility in the international circuit in the late 1940s and early 1950s propelled a larger number of people to visit the Biennale in the post-war years. In his history of the Biennale before 1968, artist and critic Lawrence Alloway writes that ‘attendance at the first of the new Biennales, spurred by the easing of travel restrictions, and by a sense of occasion at the famous institution’s renewal’, increased by over 70,000 visitors.11 Curiosity further spurred this surge in visitors, as a lack of information about artists during the Second World War had led to a greater interest in the Biennale on the part of writers and artists. According to Alloway, the European art world was ‘full of artists out of touch with one another, conscious of waiting to see Pollock or Giacometti or Dubuffet for the first time’.12

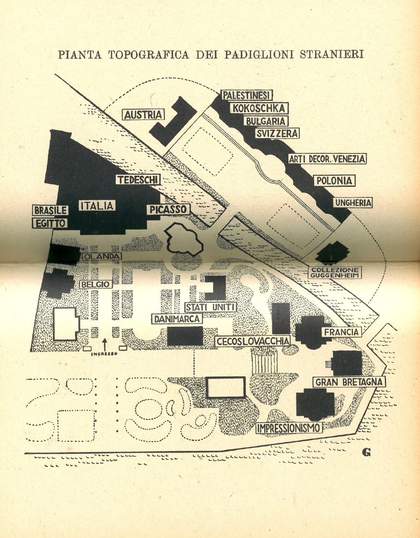

Fig.2

Map of the 1948 Venice Biennale

The international biennial in the 1950s

In the years following the end of the Second World War, the Venice Biennale maintained its national representation and increased its number of national pavilions, a recurring element of the exhibition since its beginning. From the time of its inception in 1895 and throughout the course of the 1950s, the Biennale was confined to an enclosed sector in the gardens, or giardini, on the edge of Venice’s city limits.13 Although no Biennale exhibitions took place during the Second World War, the concomitant political turmoil in Europe did not permanently impede the expansion of the Biennale, but instead ushered in a decade of changes within the institution once it resumed in 1948. A new international dynamic characterised the 1948 and 1950 Biennials. The 1948 Biennale was distinct from earlier exhibition iterations as multinational representation expanded beyond the scope of Europe to include other regions such as Brazil, Egypt and Palestine, as is shown by the Biennale map in that year’s catalogue (fig.2).14 At the same time, the location of these pavilions reflected a sense of spatial hierarchy, and spaces employed by ‘emerging’ countries contrasted with those of the superpowers that were given freestanding, permanent pavilions. The map of the 1950 Biennale indicates this increasing geographic inclusion as the exhibition began to move beyond its Euro-American confines in order to include select countries in the Middle East and Africa. In doing so, the Venice Biennale reflected the broader international dynamics, notions of hierarchy and geopolitical boundaries that were at stake in the Euro-American sphere at the onset of the 1950s.

Fig.3

General Franco (third from the left) at an exhibition organised in conjunction with the Bienal Hispanoamericana de Arte 1955 in Barcelona

The national pavilion format and its continuous occurrence every two years set the Venice Biennale apart from large-scale exhibitions elsewhere in the world in the 1950s. Non-continuous or short-lived biennial exhibitions in the 1950s include the Bienal Hispanoamericana de Arte (BHA) in Spain and Latin America, the Tehran Biennial in Iran and the Paris Biennale in France. While the names and scope of these exhibitions were similar to the Venice Biennale, they employed neither the national pavilion format nor the biannual rhythm of their Venetian counterpart. In the Spanish-speaking world, the BHA occurred three times, in three different locations. However, the BHA was neither truly biennial in timing nor continuous in format: the first iteration took place in Madrid in 1951, the second in Havana in 1954, and the third and final one in Barcelona in 1955. Indeed, coincident with the 1955 BHA, the Franco government presented Pollock’s work as part of one of the group exhibitions collateral with the BHA (fig.3).15 By the mid-1950s, the Spanish government instead opted to work with major museums and other international events with the belief that they would yield the same returns at less of a financial and political cost.16

Unlike the BHA, which strove to compete with the Venice Biennale as a pseudo-colonial and nationalistic platform in the Hispano-American world, the Tehran Biennial emerged directly in relation to the Venice Biennale as a means of selecting which works would represent Iran in Venice. The Tehran Biennial began in 1958 and ran for five iterations until 1966. Art historian Layla Diba argues that these biennials ‘led to the inclusion of the leading Iranian artists in international biennials and art galleries, yet largely failed to place their work in international museum collections’.17 The first Tehran Biennial, organised by artist Marcos Grigorian and sponsored by the Iranian Ministry of Culture, was held at the Abyaz Palace building in the Golestan Palace Complex.18 Forty-five painters and four sculptors presented work in the inaugural 1958 show, and several of these artists (Parviz Tanavoli, Marcos Grigorian and Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian) went on to participate in the 1958 Venice Biennale, which opened several months later.

In France, Minister of Culture André Malraux inaugurated the Paris Biennale in 1959, and the exhibition was held at the Musée d’Art Moderne until 1982. The institution at that time occupied the west wing of the Palais de Tokyo, whose building was the product of France’s 1937 Exposition Internationale des Artes et Techniques. Between 1954 and 1959 the Palais de Tokyo hosted the Salon de la Jeune Peinture as well as other temporary salons including the Salon de Mai and the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles from 1946 to 1960. During this period, the museum also mounted prominent exhibitions organised by other institutions, including the 1955 show 50 Years of Art in the United States. These biennial exhibitions in Spain, Iran and France were all part of government initiatives to implement large-scale events.

On the other hand, in the United States and Latin America private initiatives sought to establish a similar model and have proven themselves impervious to the changing political climate. Ongoing biennials in the 1950s include the São Paulo Biennial in Brazil and the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, both of which were established by enterprising industrialists, albeit more than fifty years apart.19 Notable perennial exhibitions in the United States hosted by museums include the Corcoran Biennial (which featured one of Lewis’s works in its 1953 iteration), the exhibition of painting and sculpture at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (which included works by Lewis in its 1950, 1953 and 1958 displays), the annual exhibition of contemporary painting at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (which included a work by Lewis in 1951) and the American drawing annual at the Norfolk Museum of Art in Virginia, now the Chrysler Museum (in which Lewis participated in 1952). While these localised perennial exhibitions in public museums in the United States served to present a greater breadth of contemporary production, the Carnegie International remained the preeminent global exhibition in the country.

Norman Lewis and the 1956 Venice Biennale

Fig.4

Norman Lewis

Cathedral 1950

Tate L03741

© Estate of Norman W. Lewis; courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

The church is omnipotent in the Venetian landscape, as the spires of Catholic churches and looming bell towers punctuate the city’s skyline and the intricate system of waterways within the archipelago. It was in this context that Lewis’s Cathedral 1950 (Tate L03741; fig.4) brought the cityscape of Harlem into dialogue with the churches of Venice. Likewise, his Untitled (Exaltation) from 1951 (private collection) explored the architecture of Harlem’s notorious neo-Gothic churches that surrounded his studio. While Manhattan’s built structures provided the principle reference for these works, the Mediterranean landscape was not unknown to Lewis. In fact, the artist had travelled through the Mediterranean and Spain in the 1950s.20 However, when Cathedral came to Venice, Harlem architecture was seen in that city for the first time.

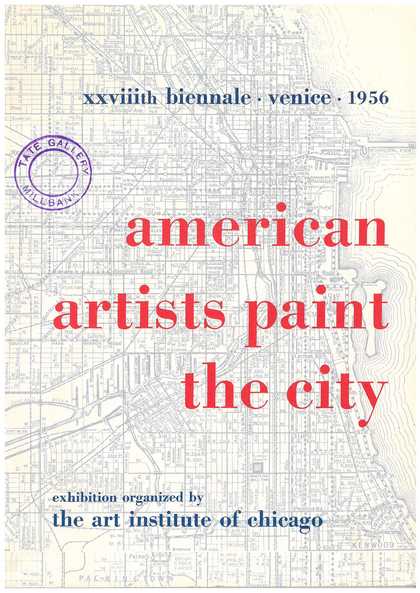

Fig.5

Cover of the catalogue to Katherine Kuh’s exhibition American Artists Paint the City, 1956

It was in this context that Lewis participated in Katharine Kuh’s 1956 exhibition for the United States pavilion, American Artists Paint the City (fig.5). For this exhibition, Kuh brought works by New York-based abstract expressionists together with other concurrent stylistic movements and mediums in contemporary American art (including realism and photography) by including thirty-six different artists from all over the country. According to Kuh, Lewis’s work falls under the broader rubric of urban cathedrals in the United States. She writes in the catalogue to the exhibition: ‘It is curious that painters often identify the skyscraper, particularly at night, with the verticality of Gothic cathedrals. Both Norman Lewis and Joseph Friebert, in canvases named Cathedral, accentuate the mystery of jewel-like luminosity.’21 Indeed, the thematic framework of the exhibition took centre stage: as art historian Mary Caroline Simpson notes, Kuh ‘envisioned an exhibition that would guide spectators through a series of comparisons between abstract and representational treatments of a common theme, the American city’.22 The involvement of Kuh, a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, was an anomaly in the landscape of 1950s exhibitions, which were commonly organised by MoMA and New York figures, and thus it is ironic that Kuh’s exhibition was the first to include Lewis in Venice.23 Furthermore, as Kuh’s biographer Avis Berman writes, ‘No woman commissioner had ever represented the United States to date, and the government authorities were not ready to break with tradition. They decreed that Dan[iel Catton] Rich would be the U.S. commissioner, and so he was.’24 This marginalisation of the curator because of her gender speaks to the contemporary sociopolitical climate. Yet the 1956 exhibition was in fact distinct from other Biennale exhibitions in the 1950s because Kuh’s framework extended outside of New York and entailed a heavy reliance on theme.

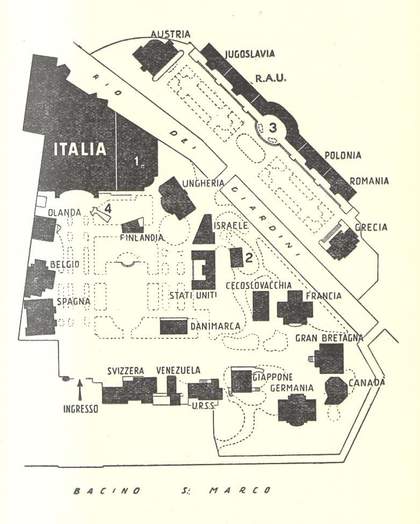

Fig.6

Map of the 1958 Venice Biennale

Although Kuh’s theme was focused on America, the Venice Biennale was a catalyst and point of departure for other perennial and international exhibitions around the world such as in Iran, France, Spain, Brazil, and even the United States. The Biennale had proven itself a crucial player in the presentation of American art in Europe and in its canonisation more broadly as the 1950s drew to a close. Furthermore, the Biennale community and its authorities officially recognised American artists for their achievements when Tobey won the 1958 City of Venice Painting Prize for his work Capricorn of the same year (private collection). The 1958 United States pavilion organised by Frank O’Hara and Sam Hunter took place in the context of a Venice Biennale that had an increasing number of participants, both in freestanding permanent pavilions and in temporary exhibitions within existing buildings (see fig.6 for the map of that year’s Biennale).25

By 1958–9 American abstract expressionism had been canonised as a monumental movement by major European institutions via exhibition and acquisition.26 Indeed, in 1958 the works of the New York School painters had achieved such iconic status that Twentieth Century Highlights, an exhibition organised by the United States Information Agency comprised solely of prints of well-known abstract expressionist paintings and other works, travelled to Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East.27 Another national show, The American National Exhibition, went to Moscow’s Sokolniki Park in July 1959, and attracted 2.7 million Russian visitors.28 In this way, the exhibition as a format had proven itself the predominant means of disseminating the visual arts internationally. Lewis’s participation in the 1956 Venice Biennale not only marks an important stage in the artist’s career, but also serves as a hallmark of the historic moment characterised by a new interest in international art exhibitions in the post-war period. The Venice Biennale served as a critical platform to inform institutional collecting strategies in then-nascent collections and provided eager audiences with an opportunity to view artworks from around the world.