Fig.1

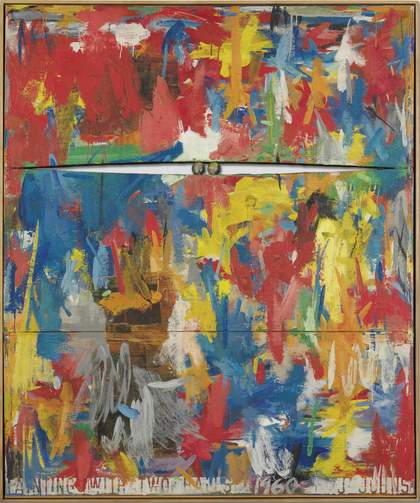

Jasper Johns

Dancers on a Plane 1980–1

Tate T03242

In 1984, when the second, 1980–1 Dancers on a Plane (Tate T03242; fig.1) was exhibited at Leo Castelli Gallery in New York City, the work’s hatching-filled surface announced its kinship with its immediate predecessor, the 1979 version of Dancers on a Plane (private collection), as well as numerous earlier works Johns had based on the same motif. Yet nothing could have represented a more decisive break with the decorous abstraction of the hatchings than the new work’s hairy ‘balls’: a scrotum-shaped cut-out piercing the bottom side of its heavy bronze frame, incised with lines suggesting pubic hair (fig.2).

Fig.2

Jasper Johns

Dancers on a Plane, detail of the frame’s lower edge

Artwork © Jasper Johns

Photo © Katherine Markoski

Fig.3

Jasper Johns

Dancers on a Plane, detail of the frame’s upper edge

Artwork © Jasper Johns

Photo © Katherine Markoski

Meanwhile, centred at the top of the frame, a kind of diagram constructed from flattened bronze shapes suggests the intersection of two figures: a positive form made up of paired, downward-pointing triangles and the negative form of a sunken vertical channel or shaft, which disappears into the cleft between the triangles (fig.3).1 Top and bottom, diagram and cut-out are precisely aligned along the work’s vertical axis, as if to emphasise the continuity of hollowed-out ‘balls’ with phallic ‘shaft’. Finally, the lower part of the imaginary plumb line connecting testes to phallus is highlighted with daubs and dashes of white paint, underscoring the connection between them, as well as their separation by the canvas itself.

Fig.4

Jasper Johns

Painting with Two Balls 1960

Encaustic and collage on canvas with objects

Collection of the artist

© Jasper Johns

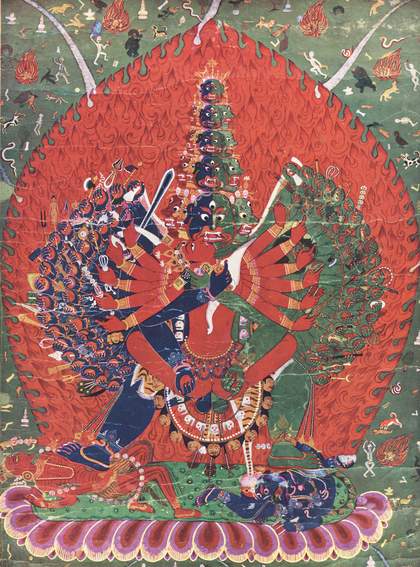

Fig.5

Mystical Form of Samvara with Seventy-Four Arms Embracing His Sakti with Twelve Arms, Nepal, seventeenth century

Gouache on cloth

711 x 483 mm

Location unknown

Frequently when Johns introduces a new motif, precedents can be found in earlier works by the artist. Commentators were quick to connect the relief elements of the frame in Dancers on a Plane to Johns’s Painting with Two Balls 1960 (fig.4), in which two wooden spheres are tightly wedged into the suggestively shaped gap that separates conjoined canvases.2 Yet the sexual imagery that literally brackets Dancers on a Plane lacks both the comedy and the literalness of the earlier work, with its punning reference to the macho studio talk of the abstract expressionists. From the bronze frame itself, to the finicky, hand-crafted appearance of the testicles, to the schematic treatment of the ‘phallus’ and pudendal cleft, everything about the 1980–1 work announces its complete lack of irony, its almost awkward earnestness. Even the frieze of knives, spoons and forks that adorns the frame cannot puncture this mood of artifice, so marked in its contrast to the sexual explicitness of the reliefs’ subject matter.

In interviews Johns has identified the source of this imagery as a seventeenth-century painting from Nepal that pictures the sexual union of the northern Buddhist god Samvara with his divine consort Vajrayogini (or Vajravarahi) (fig.5).3 He discovered this painting, he told curators Nan Rosenthal and Ruth Fine, when looking at a book on Tantric art.4 Commentaries on this source material often content themselves with quoting Johns’s own, highly elliptical explanation of the work’s subject – ‘Seeing a thing can sometimes trigger the mind to make another thing’5 – rather than brave the quagmires of art historical interpretation. While this might be attributed to his critics’ lack of familiarity with Tantric art and iconography, by 1984 the quotation of esoteric Buddhist philosophy by an American artist was already a familiar gesture. In effect, Johns’s work posed anew the question asked some twenty years earlier by his friend John Cage – ‘What nowadays, America mid-twentieth century, is Zen?’6 – only of Tantra, rather than Zen; and in the changed context of an internationally connected, late-twentieth century art world, marked by the increasingly global ambitions of contemporary artists and their dealers.

One and many Tantras

What is Tantra? A number of scholarly authorities on Tantra deny that any such thing actually exists. That is to say, the characteristics commonly associated with Tantrism do not belong to a single, unified body of religious tradition, but permeate the doctrines and practices of many different schools and sects of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism from the medieval period onward.7 As used in the sacred scriptures of the Vedas and other ancient Sanskrit texts, the word tantra broadly means ‘treatise’, ‘doctrine’ or ‘system’. The word became more specifically associated with a body of doctrines and religious traditions based upon texts known variously as agamas or tantras, a class of non-Vedic (or non-revealed) scriptures that encompass a wide variety of topics, from statecraft, to shamanic and yogic practices, to cosmology and metaphysics.8 These texts, the tantras proper, are attested from the seventh and eighth centuries onwards (although many of them assert a far greater antiquity, pre-dating even the Vedas themselves); meanwhile a number of the practices closely identified with Tantrism, including goddess worship (Saktism), blood sacrifice, ritualised sexual intercourse and magico-yogic techniques, have been traced back to sources in indigenous, pre-Vedic religious traditions.9 During the medieval period Tantric practitioners often dwelt on the margins of society, their transgressive ceremonies shrouded in secrecy: ascetic sects like the Kapalikas (‘skull-men’), who used cranium begging bowls and inhabited cremation grounds, inspired fear and awe by violating taboos against contact with dead bodies. But with the breakdown of the Gupta Empire in the sixth century and the decentralisation of power in feudal India, Tantric practices became more widespread throughout the subcontinent, as competition among local religious movements increased.10 During the same period, Tantric doctrines and rituals influenced the development of esoteric schools of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism that were exported abroad, contributing to the dissemination of Tantrism throughout Southeast and East Asia.11 Eventually Tantrism came to imbue many different strands of these religions with its characteristic philosophies and forms of worship, complicating the effort to disentangle Tantra from mainstream Hinduism or Buddhism.

Conversely, some postcolonial critics have asserted that the phenomenon known as ‘Tantra’ is a purely Western invention, an attempt on the part of orientalist scholars and colonial authorities to excise those aspects of Hinduism that struck them as scandalous deviations from the rarefied spirituality of the Vedas, which they regarded as closer in spirit to their own deistic monotheism.12 Within colonial-era histories of Hinduism, Tantra was often characterised in distinctly orientalising terms, as a corruption of a supposedly earlier (and therefore, according to the racial theories of the time, a more purely Aryan) Vedantic Hinduism.13 Consequently, Tantra would come to represent what one scholar has termed the ‘extreme Orient’, a domain of secret cults, forbidden rites and perverse and excessive sensuality.14 This interpretation influenced even the intellectuals of the Bengal renaissance: socio-religious reformers like Ram Mohan Roy (1772–1833), founder of the monotheistic religious movement known as Brahmoism, campaigned vociferously against Tantra, which he associated with the Saktism (worship of the Divine Mother) that dominated the religious practices of his own class, the upper-caste Brahmins of Bengal.15

In the West in the early twentieth century, it was precisely the promise of emancipation from the strictures of dogmatic Christianity and utilitarian rationality that rendered Tantra so attractive to Romantic orientalists like Sir John Woodroffe (author of the earliest popularising treatments of Tantra in English, under the pseudonym ‘Arthur Avalon’) and Heinrich Zimmer, as well as charismatic cult leaders like Aleister Crowley, who credited Tantra as a source of inspiration for his own brand of ‘sex magick’.16 Subsequently, in the 1960s and 1970s, Tantra was actively exported to the West by gurus and teachers from a variety of religious and spiritual traditions. The failed 1959 Tibetan uprising against Chinese communist authorities, which drove the Dalai Lama and other religious leaders into exile in India and the West, afforded Westerners unprecedented access to the esoteric traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, which includes many Tantric elements.17 In subsequent decades, the Tantric teachings of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and other Tibetan Buddhists in exile found an especially receptive audience among avant-garde artists and Beat poets, many of whom already had long-standing interests in Hinduism, Zen Buddhism and other Asian spiritual and philosophical traditions.18 Meanwhile the popular reception of Tantra in the West linked it with both sexual liberation and mysticism, resonating with the countercultural embrace of the occult, ‘free love’ and goddess-centred neo-paganism.19

The European and American reception of Tantric art is inseparable from these developments, yet it followed its own unique trajectory. Contemporary artists in India and the West were introduced to Tantric art thanks largely to the collaboration of four individuals: an Indian curator, a British pop music impresario and two art dealers, one based in London and the other in New Delhi. As will be shown below, their collective efforts launched an Indian art movement, opened new markets for Tantric art in India and the West, and created a new field of academic specialisation. At the same time, they helped expel the mists of esoteric speculation and rumour surrounding Tantra by securing its newfound visibility on the world stage.

Tantric art in the twentieth century: Nodes and networks

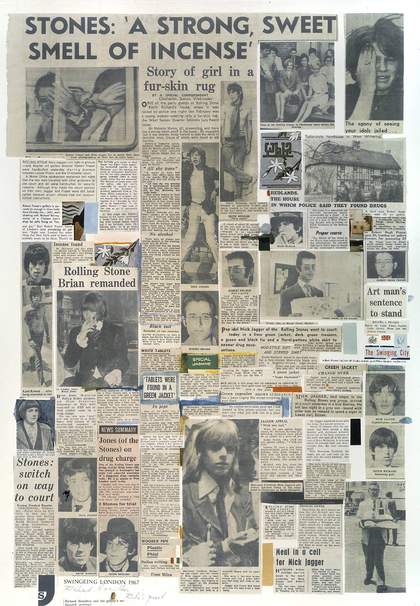

Fig.6

Richard Hamilton

Swingeing London 67 - poster 1967–8

Tate P01855

Artwork © The estate of Richard Hamilton

Photo © Tate

In 1967 London gallerist and pop art dealer Robert (‘Groovy Bob’) Fraser and Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones were arrested for drug possession at a party at Keith Richards’s country house, Redlands. Reacting to sensationalist media coverage of the case, British pop artist Richard Hamilton created a collage of press clippings that he then made into a lithograph titled Swingeing London 67 - poster 1967–8 (Tate P01855; fig.6). Special prominence is given to the headline, ‘Stones: “A Strong, Sweet, Smell of Incense”’ and its correlation of fashionable orientalism with the use of illicit drugs. Yet in the following years, Fraser would become involved with a series of projects that aimed to promote an entirely different linkage of Asian culture with the avant-garde, emphasising the continuities between Tantric art, abstract painting and experimental film.

Nik Douglas was a onetime manager and producer of English rhythm and blues groups (and distant descendent of the Duke of Buckingham) who in the 1960s and 1970s travelled extensively in India and South Asia, researching Tantra and studying Ayurvedic medicine.20 In or around 1967, he spent a year working as unpaid assistant to Ajit Mookerjee, a curator at the National Handicrafts and Handlooms Museum in New Delhi. Douglas helped Mookerjee organise the artworks in his private collection, many of which were included in Mookerjee’s 1967 book Tantra Art: Its Philosophy and Physics, and they partnered on the planning of a film that would document the 1968 Kumbh Mela festival in Haridwar. Mookerjee offered to procure access to important religious sites, including the cremation grounds where Tantric ascetics lived, if Douglas could find a sponsor for the film. Returning to London with Mookerjee’s just-published monograph in hand, Douglas met Fraser and invited him to join the venture. Together, they were able to persuade Mick Jagger to provide financial backing, in exchange for hiring Jagger’s friend, underground filmmaker Kenneth Anger, to direct the film.21

Fraser later introduced Douglas to Hugh Shaw, Secretary-General of the Arts Council of Great Britain, launching a collaboration that led to the first major exhibition of Tantric art in the West. Held in 1971 at London’s Hayward Gallery, the exhibition mainly featured works from Mookerjee’s collection. Meanwhile, Mookerjee continued to publish additional volumes on Tantra, including (with Madhu Khanna) The Tantric Way: Art, Science, Ritual (1977). The Tantric Way highlights the parallels between Tantric art and the early twentieth-century modernist abstractions of Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, Constantin Brancusi and Robert Delaunay, as well as the affinities between the post-war American painters Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman and the work of Indian artist Biren De.22 The latter was one of the leading members of a group of ‘neo-Tantric’ artists newly promoted by New Delhi gallerist Virendra Kumar Jain, the older brother of Tantra Art’s publisher, Ravi Kumar.23

Fig.7

Gouache painting on paper depicting the linga-yoni with puja (worship) offerings laid on it, Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, eighteenth century

Ajit Mookerjee Collection of Tantric Art, National Museum, New Delhi

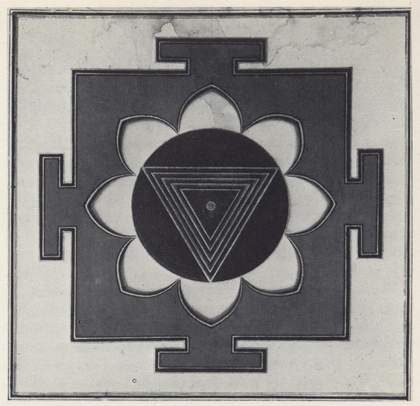

Fig.8

Gouache painting on paper depicting a Kali yantra, Rajasthan, eighteenth century

Ajit Mookerjee Collection of Tantric Art, National Museum, New Delhi

Johns has affirmed that works illustrated in Mookerjee’s books on Tantric art provided the source for most of the Tantric motifs in his 1979 watercolour Cicada (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston) and his 1980–1 Dancers on a Plane (fig.3). He has acknowledged that a number of the shapes and patterns sketched in crayon, graphite and watercolour along the bottom edge of Cicada, as well as the relief element in the top part of the frame of Dancers on a Plane, were derived from Tantric depictions of the lingam (a phallus symbolising the god Shiva) set in the yoni (a stylised vulva, symbolic of the goddess Shakti), representing the mystical union of Shiva and his consort in sexual intercourse (fig.7). Cicada draws upon at least two further images of works from Mookerjee’s collection, including a Kali yantra (a mystical diagram of the bindu or cosmic seed centred in an inverted triangle or trikona, representing Shakti; fig.8), and a drawing captioned ‘The Principle of Fire’.24

Fig.9

Bronze sculpture of the supreme Goddess as the Void, with projection-space for Her image, Andhra Pradesh, nineteenth century

Ajit Mookerjee Collection of Tantric Art, National Museum, New Delhi

Meanwhile Johns has stated that the ‘balls’ framing the bottom of Dancers on a Plane were inspired by the pendulant testicles of Samvara in the seventeenth-century Nepalese painting Mystical Form of Samvara with Seventy-Four Arms Embracing His Sakti with Twelve Arms (fig.5), illustrated in Mookerjee’s Tantra Art.25 The testicles at the bottom and the lingam at the top of the frame of Dancers on a Plane are connected by the vertical axis of the painting, whose lower reaches are punctuated with drops of white paint that could represent the beaded necklaces or girdles of Samvara and his consort,26 but also the upward flow of semen.27 An intriguing parallel may be drawn between the painting’s heavy bronze frame and a nineteenth-century sculpture in Mookerjee’s collection figuring ‘the supreme Goddess as the Void’ (fig.9), which could have inspired or at least influenced Johns’s conception of the work.28 Finally, Johns has linked the rows of cutlery that line either side of the painting’s frame to the manifold attributes held by Samvara’s seventy-four arms: these range from the Tantric symbols of the vajra (thunderbolt) and bell, representing skilful means and wisdom, to the weapons he wields in his conquest of ignorance.29 In fact, although Johns’s identification of Samvara and his consort as ‘dancers on a plane’ plays upon their resemblance to images of the dancing Shiva, Samvara’s pose is alidha asana, the lunging ‘warrior stance’. Embraced by his consort, he stands astride the two defeated Brahmanical deities, Bhairava and Kalaratri, who represent the (vanquished) illusory distinction between worldly existence and nirvana.30

Johns has not described how or when he first became interested in Tantra, or the circumstances under which he discovered Mookerjee’s work, but in the late 1960s he and Fraser travelled in the same social circles: both attended dinners hosted by New York society hostess Panna Grady, and the pop artists in Fraser’s stable included a number of Johns’s close friends and acquaintances, including Jim Dine and Richard Hamilton.31 It may be that Johns succumbed to the fascination Tantra inspired in so many other Western observers, for whom it represented the ultimate object of forbidden knowledge, a paradoxical fusion of the Romantic myth of ‘spiritual Asia’ and orientalist fantasies of sexual transgression. Conversely, his engagement with Tantric art could be considered a product of the philosophical and scholastic interpretation of Tantra advanced by Mookerjee and the writer and curator Philip S. Rawson, which aimed to reclaim Tantra from its popular associations with sex orgies and drug use.32 Yet Johns’s quotation of these images performs a series of gestures – appropriation, decontextualisation, fetishisation – that are all too familiar from the history of colonialist and orientalist representations of Asia as Western civilisation’s ‘other’.

But what if such colonial structures of power and representation could be subverted in the very process of cultural translation? What if Tantra could be mined for a metaphorics that subverted orientalism’s own structuring oppositions between iconicity and mobility, fetishisation and exchange? The next section will show how Tantric imagery gave metaphorical expression to a competition over the artistic leadership of Cunningham’s dance company, and how Johns drew upon this conceptual map or mandala to formulate his own, divergent conception of the relationship between sexual and cultural difference in his 1980–1 Dancers on a Plane.

Geographies of the readymade

Fig.10

Robert Rauschenberg’s set design Tantric Geography for Merce Cunningham’s Travelogue 1977, with a dancer performing a piece by Cunningham

Installation view from the exhibition The Bride and the Bachelors: Duchamp with Cage, Cunningham, Rauschenberg and Johns, Barbican Art Gallery, London 2013

Photo © Felix Clay 2013

In the late 1970s, even as Johns curtailed his involvement with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, he might have taken special note of the set Robert Rauschenberg designed for Cunningham’s dance Travelogue 1977, a sculptural installation that Rauschenberg titled Tantric Geography (fig.10).33 The set design was related to a series of works Rauschenberg created in 1975 and 1976 entitled Jammers, which also made use of fabric panels reminiscent of flags or sails, and whose brightly coloured skeins of cotton, muslin and silk drew inspiration from the artist’s 1975 visit to Ahmedabad in India to research textiles and printmaking. The resemblance to flags of the fabric panels in both Tantric Geography and the Jammers series was probably not lost on Johns, who might have seen a winking reference in these works to his own iconic paintings of the American flag.

Beyond swathing the stage in curtains, one of the most striking features of Rauschenberg’s décor for Travelogue was the frieze of alternating chairs and bicycle wheels installed along the wall at the rear of the stage. Suggesting the arrangement of a chair before a spinning wheel, the frieze extends the metaphorical connotations of the fabric to incorporate iconographic associations with textile production.34 At the same time, the pairing of bicycle wheel and chair inescapably evokes Duchamp’s famous ‘assisted readymade’ of 1913, constructed from a bicycle wheel mounted upside-down on the seat of a wooden stool (Bicycle Wheel remade 1951, Museum of Modern Art, New York). Meanwhile, the wheels recalled an earlier set Rauschenberg had designed for the dance company’s tour of India in 1964, which featured a bicycle suspended above the stage;35 for their part, the chairs could be seen as a nod to Cunningham’s celebrated choreography for Antic Meet 1958, in which he danced with a chair strapped to his back. The chairs also call to mind Rauschenberg’s iconic 1960 painting Pilgrim (private collection), which features a real wooden chair affixed to its surface, as well as two important 1964 works by Johns, Watchman (The Broad Art Foundation, Los Angeles) and According to What (private collection).

Both chair and bicycle wheel, then, might be said to belong to a shared iconography of the Duchampian readymade, a tradition to which Johns, Rauschenberg and Cunningham were all equally bound. In this sense, these objects represent a point of convergence between the artists’ individual oeuvres. At the same time, Rauschenberg’s negation or reversal of Duchamp’s foundational act in constructing Bicycle Wheel in 1913 – separating the two components, chair and wheel, that Duchamp had originally fused in order to produce the first readymade – suggests a very different possibility: namely, that the frieze enframing Tantric Geography, with its alternating elements that face sometimes towards, sometimes away from one another, represents two incompatible or opposed interpretations of Duchamp’s foundational work. The bicycle wheel interprets the readymade as a literal ‘vehicle’ for the frictionless circulation of artworks and artists across geographic and political borders, suggesting the mobility of the post-studio artist whose materials, being found or shop-bought, are always ready at hand: it links the readymade to Duchamp’s Boite-en-valise 1935–41, a suitcase he designed to house a collection of miniaturised reproductions of his major works (editions of the Boite-en-valise are held in various collections).36 This was indeed the interpretation of Duchamp’s work that guided Rauschenberg’s own artistic practice, characterised by its multiple, transnational sites of production and the affirmation of spatial mobility as an aesthetic value in its own right.37 Rauschenberg’s ‘combines’, hybrid assemblages of painting, collage and sculpture of which Pilgrim is an example, have their origin in the moveable sets Rauschenberg constructed for Cunningham’s dances, such as Minutiae 1954; other works, such as Monogram 1955–9 (Moderna Museet, Stockholm), are themselves mounted on casters or incorporate moving, mechanical parts. Of equal significance is Rauschenberg’s embrace of mobility in his personal and professional life, such as when he joined Cunningham’s company as set designer and occasional performer on their 1964 world tour, simultaneously taking advantage of the opportunity to raise the international stature of his art.38

In contrast to this Rauschenbergian reception of the readymade, there is the interpretation advanced by Johns, for whom the readymade embodied the paradox of a work of art that is simultaneously reduced to the mute passivity of the everyday object, and elevated to the purely ideational condition of the emblem or sign.39 This is the readymade as icon, partaking of both materiality and transcendence. Brought down from its pedestal or cantilevered out from the wall, the work of art is made tactile, embodied and concrete; at the same time, reduced to its purely conceptual, linguistic or imagistic essence, the material object is transformed into a hieratic symbol, unchanging and immutable.40 In Tantric Geography this Johnsian interpretation of the readymade might be succinctly symbolised by the chair, which ever since Plato has served as a privileged example of the distinction between the material object (the chair on which the philosopher sits and thinks) and the pure Idea (the ideal image or unchanging ‘essence’ of chairness, in relation to which every actual chair is merely an imperfect and impermanent copy).

Even as the chair encapsulates a reading of the readymade-as-icon, it also attests to another aspect of Johns’s difference from Rauschenberg. In contrast to the latter artist’s wheeled and mechanised constructions, even the moveable and interactive components of Johns’s paintings – hinged, hooked and swinging elements – suggest immobilisation and storage, as of an object removed from use and fixed in place. To this corresponds an image of the artist as hermit or recluse, confined to making art out of whatever lies at hand, most saliently the accoutrements of the studio (paint cans, rulers, brooms and cups) and the furnishings of his home (cutlery, cabinets, clotheshangers – and, of course, chairs). Meanwhile, aside from an extended visit to Japan in 1964, Johns did not seem to share Rauschenberg’s enthusiasm for travel: during the 1970s, he largely divided his time between his Houston Street studio in New York City, acquired in 1967, and residences in upstate New York, on Edisto Island in South Carolina, and on the Caribbean Island of Saint Martin.

This division between the two artists’ lives and works neatly recapitulates the polarity suggested by the title of Rauschenberg’s set design, with its opposition of the bodily and the spatial, immanence and transcendence. A work designed for interaction with human bodies moving through space, Tantric Geography evokes one of the key principles of Tantra: the analogical relationship between the microcosm of the human organism and the macrocosm of the cosmos, with its sacred geography of temples and pilgrimage sites, each keyed to a particular body part of the Great Goddess.41 Insofar as the all-embracing Divine Mother participates in the limitations of the geographic and the corporeal, Tantra both recognises and resolves the contradiction between the multiplicity of bodies and the unity of the purely transcendent reality or Idea. This characteristically Tantric solution to the opposition between oneness and multiplicity might have appealed to Rauschenberg as a way of describing the relationship between the work of the two artists, reconciling while respecting their individual differences. Moreover, this was a reconciliation peculiarly tuned to the multiple spaces – geographic, theatrical and sexual – inhabited by Cunningham’s globe-trotting ‘dancers on a plane’.

Might the Tantric content of the 1980–1 Dancers on a Plane be read as Johns’s response to his interpellation within Rauschenberg’s set design? To answer this question it is necessary to go back to the painting from which Johns’s imagery derived. Although the earlier watercolour Cicada featured Tantric imagery taken from a variety of sources, interspersed with found images taken from newspaper photographs and entomological illustrations, Johns has related the various Tantric elements of Dancers on a Plane to one single source, as mentioned above: a seventeenth-century Nepalese painting depicting Samvara joined in sexual union with his divine consort, Vajrayogini. The specificity of the references in Dancers on a Plane – the reflections of Samvara’s testicles and the act of sexual penetration in the frame’s bronze reliefs; the translation of the beaded tassel hanging from Samvara’s girdle into the dotted white line dividing the painting along its axis; and the cutlery’s evocation of the weapons borne in Samvara’s out-fanned arms – frames Johns’s engagement with Tantra as a direct, one-to-one relationship between his own painting and the anonymous Nepalese painter’s work, a face-to-face rapport across a gulf of centuries and a distance of thousands of miles. This creative conjunction, spanning a divide of almost cosmic proportions, precisely mirrors the iconography of Samvara’s world-engendering union with Vajrayogini. It is tempting, therefore, to interpret the Tantric theme of Dancers on a Plane as a commentary on, or condensation of, Johns’s multiple engagements with other cultural traditions, as in prior works like Usuyuki 1977–8 (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland). In the Tate Dancers on a Plane, cross-cultural exchange is represented not as a function of the mobility of artists or artworks across borders, but as a product of intersubjective encounter, framed by erotic and ideological investments in cultural difference.42

Such an interpretation is supported by what we know of Johns’s actual relationships with people and institutions outside the United States. If the rivalry between Johns and Rauschenberg had partly to do with competition for international exposure and engagement, then the peripatetic Rauschenberg could indeed claim a wider scope of activity than Johns; and yet Johns’s foreign engagements, while few in number, tended to be deep and long-lasting. In his relatively rare travels outside the United States, he frequently visited places he had already seen in order to reconnect with people he knew, such as the Japanese critic Tono Yoshiaki, his long-time friend and supporter, or Swiss-born curator and art historian Christian Geelhaar.

Finally, we might note that the encircling girdle of spoons, knives and forks in the bronze frame of Johns’s painting parallels the frieze of alternating chairs and bicycle wheels in Rauschenberg’s Tantric Geography, while simultaneously recalling fork-and-spoon pairings found in a number of the artist’s earlier works. The motif makes its first appearance in Johns’s painting In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’ Hara 1961 (Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Chicago), a work that art historians Fred Orton and Kenneth Silver have both linked to the break-up of Johns’s romantic relationship with Rauschenberg in that year,43 suggesting that the mismatched pairing of spoon and fork could serve as a symbolic portrait of Johns and Rauschenberg themselves – two ‘opposites’ joined by elective affinity, their differences irreducible to the fixed binary oppositions prescribed by gender.

Perhaps, then, Johns’s resurrection of this motif in the Tate Dancers on a Plane represents a response to the chair-and-wheel motif framing Rauschenberg’s set, which it formally echoes. Significantly, however, the frame of Johns’s work features not two elements, but three: the spoon, the fork and the knife. Who or what, in this triangulation of metaphors, would be represented by the knife? Is the knife simply the cut, the division, that separates their respective interpretations of the readymade? Or does this ‘cut’ in fact stand for something more immediately concrete, a channel of communication as well as an object of rivalry: for example, the dance company for which both artists designed costumes and sets?

Irreducible to the binary structure of sexual difference that regulates Tantric ritual, these knives could stand for many things, including sexual difference itself, or the violence that accompanies differentials of power and position in every situation of exchange, whether sexual, artistic or political. Meanwhile, the paired emblems of vagina above and testicles below unceasingly pose the question of who is the active and creative partner, and who the passive participant, in the work’s ever-expanding circuits of exchange.