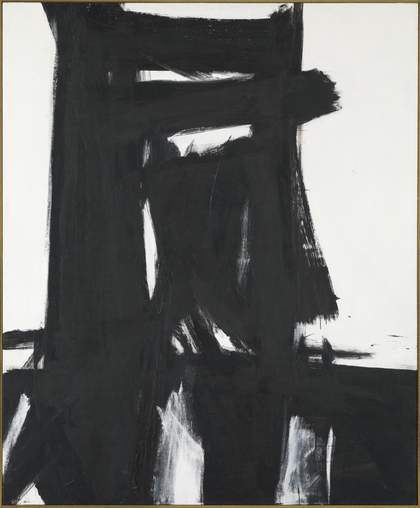

Fig.1

Franz Kline

Meryon 1960–1

Oil on canvas

2359 x 1956 mm

Tate T00926

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2017

Franz Kline’s Meryon of 1960–1 (Tate T00926; fig.1) is a large-format, vertically oriented abstract oil painting on canvas that was executed in the particular bold gestural style and black and white palette for which the artist initially rose to prominence in late 1950. It belongs to a group of paintings, dating to the early 1960s, in which Kline abandoned his recent attempts to work with colour and grey and reverted to a palette almost exclusively consisting of black and white. In Kline’s hands, this already inherently limited palette was further restricted in order to maximise tonal contrast and thus heighten visual impact. As can be seen in Meryon, the blacks and the whites of this palette were not blended to produce a subtle tonal range of intermediary greys but instead preserved intact, starkly, as black and white.

The composition of Meryon roughly consists of a series of black, vertical, concentric rectangular forms atop a black horizontal base. The painting’s visual impact is chiefly a product of this structure’s contrast with the whites that appear to surround the structure, including internally and at its foundations, so that it threatens to collapse. The work’s formal drama, then, takes place primarily within the black brushstrokes of the structure, as it struggles to maintain the uprightness that is dictated by the shape of the canvas. In addition, there are resolutely gritty, disparate episodes of action and friction where the blacks and whites interface, whether in the tense boundaries between the structure and surrounding space, or within the still distinct layers of overlapping black and white.

When Kline first came to public attention he used inexpensive commercial house paint, not the sumptuous oil paint more commonly employed in fine art and that he later used to make Meryon. However, even in Meryon the oil paint has been thinned with turpentine into a considerably less viscous medium, like house paint, and, also like house paint, has been run over the canvas with a broad brush. Even though there are no areas in which the canvas of Meryon is left bare and it is mostly covered with many layers of paint, the fact that the paint is so thin means that the weave of the canvas resists it and emerges as an ambiguous surface texture and pattern. The canvas support is thus not only visible through the paint but is asserted as a material presence, if not as a medium in its own right. Meryon is not an illusionistic painting with pretensions towards three dimensions, but instead a dry, matte, massive and yet shallow object with the quotidian quality, when viewed askance, of a stuccoed wall. Although it has been made to look spontaneous, as per the stereotype of the abstract expressionist painter who works on instinct, it is well known that Kline depended heavily upon sketches in order to work out the compositions of his paintings in advance. No preparatory drawings have been linked to Meryon, but our knowledge of Kline’s working process suggests that the composition of the painting was deliberate and can be treated as part of its larger puzzle.

The vertical format and gigantic proportions of Meryon prepare the viewer for a portrait painting of a larger-than-life individual. But the traditional portrait called for by the painting’s format and the proper noun in its title – the surname of nineteenth-century French printmaker Charles Meryon – is answered by what appears to be an entirely abstract composition. Beyond its initial visual impact, Meryon thereafter challenges the viewer to square the proposed content of the painting with its forms, which lack any record of an individual likeness. Meryon is an abstract painting whose peculiar visual and verbal puzzle calls into question the main imperative of abstraction, which is the creation and consideration of artwork without any outside references. It demands patient, extended contemplation, as well as some rarefied cultural knowledge, at least as much as Kline exhibits to the viewer in the painting’s title regarding the history of French printmaking. The allusion to the legendary etcher, who worked on a small scale with a fine needle, recasts Kline’s bold gestural abstraction, which was produced with a broad brush in ostensibly rapid, improvised strokes.

In a review of Kline’s exhibition of new paintings at the Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, in December 1961, in which Meryon debuted, artist and critic Donald Judd stated of Kline’s recent reversion to black and white: ‘At present his style allows him either to repeat himself – not quite, since he is aware of the repetition – or to add complexities which restore naturalistic distinctions originally expunged.’1 This In Focus interprets Meryon in terms of Kline’s self-aware ‘repetition’, as well as the related ‘complexities’ that are the consequence of the restoration of ‘naturalistic distinctions originally expunged’, primarily stemming from Kline’s title. Meryon, in sum, forces us to ask what motivated Kline’s late return to his earlier palette of black and white and, when analysed in context, provides us with a set of specific answers, and more.

The critics and the stakes

When Meryon was first exhibited at the Sidney Janis Gallery alongside Kline’s other recent paintings in December of 1961, some critics were struck, unfavourably, by the similarity of these works on the whole to Kline’s first abstract paintings in black and white. ‘His paintings have had a familial resemblance that was, in general, too strong’, wrote Brian O’Doherty in the New York Times.2 ‘Kline still paints black cataracts of paint pouring angrily and destructively across large canvases of white’, concurred Emily Genauer in the New York Herald Tribune, concluding that ‘The major statement is what it’s always been, and growing monotonous’.3 The judgment of Judd, who was both critic and artist, was the most severe: ‘The current show has nothing equal to the Klines of the first half of the fifties, few paintings that even simulate their coherence and some that are actually bad.’4 Kline was being ‘inspected’, O’Doherty admitted elsewhere, ‘for signs of change as closely as a plate of blood agar in a laboratory’.5

The ironic assumption underlying these critics’ search for ‘signs of change’ was that this highly anticipated and desired shift would necessarily come in the form of colour or grey and so continue the foray into these palettes that Kline had undertaken in his large-format paintings of the mid- to late 1950s (see Untitled 1957, private collection, and Black Reflections 1959, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Change, in this mould, was linear, moving in a forward direction. To the disappointment of the critics, however, the exuberant colour and stormy greys that had characterised Kline’s canvases prior to these were now barely present. These critics did not recognise and therefore problematise Kline’s return to and insistence upon the black and white palette as constituting a significant ‘change’ that was worthy of consideration and explanation in itself.

Kline’s emphasis on large-format black and white paintings in this 1961 exhibition forces us to ask what motivated Kline’s reversion to his earlier palette. This was a severely reduced palette which, in combination with Kline’s bold gestural style, was itself appraised in terms of change and indeed hailed as a ‘breakthrough’ – a term and concept with broader relevance that will be examined critically at length elsewhere in this In Focus.6 An analysis of Meryon answers the primary question that Kline’s later group of black and white paintings arguably poses and, more fundamentally, demonstrates how Kline engaged proactively during the early 1960s with the wider ‘inspection’ of his oeuvre that was then underway.

Judd, the 1961 exhibition’s harshest critic, and Georgine Oeri, its most ardent defender, perhaps had a better sense of what was at stake than O’Doherty and Genauer. The question of whether or not Kline should pursue his experiments in colour and grey had already largely been settled. Even as O’Doherty and Genauer encouraged the artist to focus on colour, there was a critical consensus emerging that this effort, too, had failed.7 As Judd put it, ‘Anyway there is no reason why there should be color’.8 Judd, too, was searching the exhibition for signs of change: ‘Kline cannot advance without a drastic change’, he stated, before going on to observe that ‘At present his style allows him either to repeat himself – not quite, since he is aware of the repetition – or to add complexities which restore naturalistic distinctions originally expunged.’9 At stake in the exhibition was the viability, a decade later, of Kline’s original ‘drastic change’, or his breakthrough style, with its palette of black and white, which constituted Kline’s artistic identity and accomplishment and to which Kline was seen to owe his reputation. In this sense Judd was characterising this decade-old breakthrough in abstract painting as a dead end in 1961, from which one could only retreat in a direction of less abstraction. By contrast, in her defence of Kline, Oeri rhapsodised about Kline’s breakthrough:

Not too much more than ten years ago Franz Kline had his first one-man show at Charles Egan’s Gallery (in 1950). He was forty then. He is only fifty now. But it seems long ago; it feels like several decades in a row. The gallery was a little cubicle under the roof, four flights up, with an elevator that was usually out of order. Kline stood in there alone among his imperious off-spring like one of those Gothic statues whose small feet seem too delicate to hold up the dominant head erect on broad shoulders. In nodding toward the stirring black and white monsters in the round he asked Egan, ‘You really think, this is something?’ Naturally, he did not mean to ask ‘Do I have merit?’ He knew that. He wanted to know ‘Have I affirmed it? Did it get done?’ Nobody had yet heard of Franz Kline, nor had he. There was no way to know; while lightning and thunder were happening up there. The unknown was obviated. It was obvious, but unknown.10

Whereas Judd had doubts about abstract painting and would, indeed, soon develop out of it what he called ‘Specific Objects’, which were ‘neither painting nor sculpture’, Oeri continued to believe in abstract painting, arguing, moreover, that: ‘Kline is one of those who still affirm picture-making as a valid enterprise.’11 Ultimately, then, it was not only Kline’s detour into colour or his original breakthrough style that was being ‘inspected’ in the exhibition of paintings in which Meryon debuted, but also the viability of abstract painting as a tradition. This In Focus will demonstrate that Kline reframed the traditional range of abstraction as a style and painting as a medium by building an analogy to illustration and printmaking in Meryon. Kline’s artistic background in these areas predated and informed his breakthrough in abstract painting in the late 1940s, which Meryon then re-presented in 1961.

From Paris, to Venice, to Washington, D.C., to London

During the early 1960s the ‘inspection’ of Kline’s work was not only occurring locally, in New York City, where Kline had lived and worked for decades, but also nationally and internationally. In June and July of 1960, a year and a half before Meryon’s debut, Kline took his first and only trip to Continental Europe, where he briefly journeyed to Paris, including making a reluctant visit to the Louvre, and received a prize at the Venice Biennale.12 Kline was one of four artists chosen to represent the United States at the Biennale, which was then, as now, the global art world’s premier contemporary art exhibition.13 On the basis of a retrospective exhibition that surveyed his abstract works, starting with his quintessential ‘breakthrough’ painting Nijinsky of 1950 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), Kline was the only American to be awarded a prize at the 1960 Biennale, although not without significant controversy.

In a tale that will be retold in detail elsewhere in this project, Kline reportedly punched Jean Fautrier – a pioneer of post-war French abstract painting – in the jaw, when Fautrier confronted and insulted Kline in a Venetian café.14 Like Kline, Fautrier also won a prize at the Biennale that year, but his was a greater one: while Kline was awarded the Ministry of Public Instruction Prize of 1,000,000 Lire, one that seems to have been invented for the occasion, Fautrier received the Grand Prize for painting, which Hans Hartung, a leader of the French school of lyrical abstraction, received at the same time. The animosity between Kline and Fautrier was born of the well-known rivalry at the time between the French and American schools of abstract painting, for which the Venice Biennale served as a primary battleground and, as historian Nancy Jachec has argued, as an international arbiter, partly through its distribution of prizes.15 In spite of its abstraction, Meryon figures into this rivalry, first of all through Kline’s titular reference to the nineteenth-century French printmaker Charles Meryon. Meryon was probably begun in late 1960, after Kline returned to New York from his brief trip to France and his sensational encounter with Fautrier. This In Focus study will take into account the timing and interrogate the meaning of Kline’s esoteric take on French tradition for the cognoscenti, as well as its meaning to the uninitiated, outside of the art world, analysing how these meanings unexpectedly coalesce and live up to the lofty ideals of abstract expressionism, the American avant-garde artistic movement of which Kline was a part.

Fig.2

President John F. Kennedy and French Minister of Culture André Malraux arriving at the White House with their wives for a dinner held in honour of Malraux, 11 May 1962

Abbie Rowe, White House Photographs, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

In May 1962, a year and a half after the debut of Meryon, Kline died of rheumatic heart disease at the age of fifty-one. By that time abstract expressionism had become official insofar as it was publicly serving to represent American culture abroad. Indeed, in May 1962 Kline was invited to attend a glamourous state dinner at the White House hosted by President John F. Kennedy in honour of the French Minister of Culture, André Malraux (fig.2). By the evening of the event, however, Kline found himself in New York Hospital, where he died two days later. ‘Those few of us who know of his true condition,’ wrote abstract expressionist painter Robert Motherwell a few months after Kline’s death, ‘not from him, but from his doctors – watched in helpless dismay the chances he took. But if he could have taken care of himself, he would not have been that enchanter we all knew, as Franz Kline, generous and heedless.’16 Kline’s move from his birthplace – the coal-mining town of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania – to a bohemian adulthood in New York, where he was evicted repeatedly for failure to pay rent, was typical of the experiences of his abstract expressionist peers. These experiences culminated, despite personal struggles, poverty and public scepticism about the validity of abstraction, in the highest form of cultural recognition.

‘For art is not just an embellishment of life’, pronounced President Kennedy in his remarks at the 1962 dinner. ‘It is the expression of man’s deepest instinct – the instinct to create; it symbolizes the very essence of our being. In art man does not just distract himself; he fulfils himself.’17 This description fairly accurately encapsulated the abstract expressionist conception of art, which, despite its abstract style, was resolutely opposed to the notion of art for art’s sake, espousing rather a morality of individual responsibility that was inherently collective. It emerged under the combined influence of Jean-Paul Sartre’s fashionable existentialist philosophy and his art criticism, in which artists were assigned and assumed the special burden, after the calamity of the Second World War, of restoring humanity to society.18 As one leading abstract expressionist, Barnett Newman, explained in 1948: ‘Instead of making cathedrals out of Christ, man, or “life,” we are making it out of ourselves, out of our own feelings.’19 This was likewise the rationale that Irving Sandler, then a critic and later a historian of abstract expressionism, offered in his review of the exhibition of paintings in which Meryon debuted at the Sidney Janis Gallery in late 1961. ‘Indeed,’ wrote Sandler, ‘the social value of Abstract Expressionism lies precisely in the preoccupation of artists with the realization of individual identity in the powerfully felt esthetic experience. Miguel de Unamuno has written “that when a man affirms his ‘I,’ his personal consciousness, he affirms man, man concrete and real, affirms the true humanism.”’20 This In Focus argues that Meryon was, true to this model, at once a realisation and a revelation of Kline’s individual and thus the collective American identity.

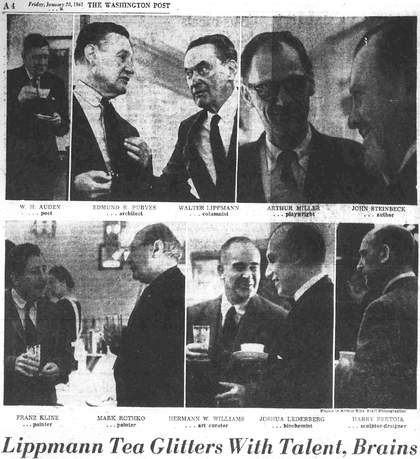

Fig.3

Jean White, ‘Lippmann Tea Glitters with Talent, Brains’, Washington Post, 20 January 1961, p.A4

Elisabeth Zogbaum papers regarding Franz Kline, 1928–1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Whereas Kline’s prize was controversial in Venice in 1960, his reputation was assured in the United States. Kline was one of the ‘cultural leaders’ who was officially invited to the inauguration of President Kennedy in January 1961.21 This invitation was only the first that the White House would extend to the painter as part of a larger new national cultural policy that privileged the contemporary arts, both performing and fine, and sought to remake Washington, D.C. as a cultural as well as a national capital.22 On the day that Kennedy was inaugurated, Kline attended an afternoon tea in the Washington home of the influential journalist and public intellectual Walter Lippmann – a gathering of celebrity intellectuals that was covered in a photo-spread in the Washington Post (fig.3).23 Other guests, also photographed for the newspaper, included poet W.H. Auden, playwright Arthur Miller, novelist John Steinbeck and Kline’s fellow abstract expressionist Mark Rothko.

Kline had not campaigned for the election of Kennedy, but he had painted campaign posters for a previous nominee of the Democratic Party, Adlai E. Stevenson, when he ran for office in 1952.24 Stevenson, who would serve as United States Ambassador to the United Nations in the Kennedy administration, even visited Kline’s studio in New York in 1959 in order to learn more about abstract expressionism, a visit that was reported in the New York Times.25 At the time that Kline completed and debuted Meryon, therefore, the painter had a public presence and a role in helping to represent the cultural politics and the liberal politics of the new establishment. Kennedy and Stevenson, when the latter was still harbouring ambitions of another run for the presidency, variously sought to affiliate themselves with the achievements of the American artistic avant-garde. For Kline, who had been opposed to the election of Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower, who served as President from 1953 to 1961, the politics of the time were congenial.

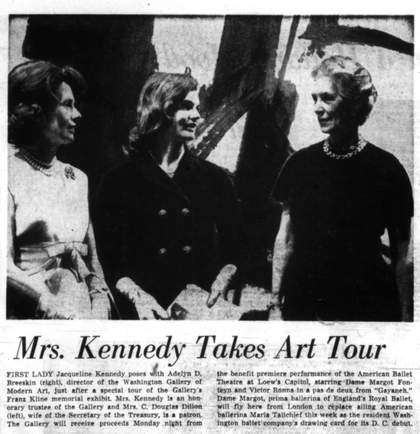

Fig.4

‘Mrs. Kennedy Takes Art Tour’, Washington Post, 9 Dec 1962, p.F2

Shortly after Kline’s death in 1962, the brand new Washington Gallery of Modern Art, in its debut exhibition, held a ‘memorial exhibition’ for Kline in which the work’s Americanness was foregrounded in the catalogue and the press surrounding the show.26 The gallery’s director Adelyn D. Breeskin, who curated the exhibition, celebrated the work’s ‘completely American quality’.27 Kline was canonised as a heroic, American avant-garde artist, while his work served to substantiate the need for such a gallery of modern art in the nation’s capital. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, who was an honorary trustee of the gallery, visited the memorial exhibition, took a private tour with Breeskin and posed for photographers in front of Kline’s Shenandoah Wall of 1961 (private collection) (fig.4).28 At least in this instance, on that day, Kline’s work served as a prop and a backdrop in the self-fashioning of the Kennedys, a process of identity formation and expression that no longer occurred, as centuries before, in portrait painting, but rather took place in the publicity photographs that circulated in the mass media.29 Kennedy was putting her support of advanced American art on show, and the Kennedys were in turn providing the kind of state patronage that was the dream of American artists both past and contemporary.30 ‘Mrs. Kennedy had said she was going to redecorate the White House and every abstract-expressionist in America had had palpitations’, the writer and collector Lincoln Kirstein joked in the Nation in February 1961.31

The retrospective exhibition of Kline’s work in Washington, which opened within six months of the artist’s death, would be the first of a series of Kline retrospectives held in the 1960s, including in 1964 and 1967 in London. Meryon was exhibited in 1964 at the Tate Gallery while a retrospective of Kline’s work hung at the Whitechapel Gallery, and the painting was exhibited at the Marlborough-Gerson Gallery’s retrospective in 1967 and was acquired by Tate directly from the show.32 In 1967, as minimalism began to make the bright colours and advertising imagery of pop art look old fashioned, Meryon acquired new relevance, and not only because of its severe palette and abstraction. As much as Judd had criticised Kline’s late black and white paintings when they debuted in 1961, Kline’s oeuvre was being interpreted throughout the 1960s as emphatically American in spirit, physically assertive and even, as is shown elsewhere in this In Focus, evocative of post-war American industrial power – exactly the terms in which Judd couched the defence of his ‘Specific Objects’ in 1965.33

Meryon’s significance

Relative to his contemporaries Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, with whom he spent many boozy nights at the Cedar Tavern in New York’s bohemian Greenwich Village, Kline remains under-studied.34 Indicatively, there are only a few fleeting references to Meryon in the published literature. Meryon has significance for Kline’s oeuvre as a whole because it both forces the question and offers a set of answers regarding Kline’s reversion, near the end of his life, to his ‘breakthrough’ palette of black and white. It was created at a moment when Kline’s oeuvre was becoming the subject of retrospective exhibitions, and the painting is retrospective in itself. Meryon can be interpreted as Kline’s contribution, shortly before his death, to the evaluation and, soon after his death, to the canonisation of his oeuvre. More broadly, Meryon provides an opportunity to rethink the notion of the ‘breakthrough’, which was crucial to the artistic experience and critical interpretation of abstract expressionism and remains a major theme in the scholarly literature on the movement. This In Focus therefore begins with a revisionist account of Kline’s development and role in the abstract expressionist movement, both of which Meryon forces us to reconsider.

The remainder of the project then makes the argument that Meryon is multiply significant: as Kline’s retrospective rumination on his artistic origins and enduring interests in illustration and printmaking; as a painting which, in its emphasis on illustration and printmaking (two forms that are conventionally opposed to both abstraction and painting), contains an implicit recommendation for how to view Kline’s abstract paintings alternatively; as a reclamation of the distinctive type of black and white gestural abstraction that Kline debuted in 1950 and so an affirmation of his artistic identity, when this identity was under both scrutiny and threat in the early 1960s; as a diplomatic, conciliatory gesture – following the incident in Venice with Fautrier – towards French abstract painters that pays homage to a nineteenth-century French artist and so points out their common heritage; and, finally, as a depiction of a conglomerate national landscape that combines the urban, the industrial and the suburban in order to provide an abstract picture of America at mid-century within the broader international context of modernity.