The Argentine artist Liliana Porter has developed a multifaceted body of work since the 1960s, using engraving, photography, installation and video to deploy an aesthetic described by Inés Katzenstein, a long-time commentator on Porter’s work, as ‘an act of knowledge that employs humour as its methodology’.1 The portfolio Wrinkle 1968 (Tate P13236; fig.1), which consists of two offset printed texts and ten photo-etchings, was produced at an early stage in the artist’s career. After settling in New York in 1964, Porter joined forces with two other artists, the Uruguayan Luis Camnitzer and the Venezuelan José Guillermo Castillo, to create the New York Graphic Workshop, a collective interested in redrawing the rules defining the discipline of printmaking, and in questioning the artificial value assigned to artworks by New York’s art market. It was in this context that Wrinkle was produced.

This In Focus examines the technical, formal and poetic characteristics of Wrinkle, and situates it as a seminal work in Porter’s artistic trajectory. This first section accounts for the making and iconography of the work and, in particular, the image of the wrinkle as a recurrent motif in the artist’s production. It looks at the possible meanings of Wrinkle in relation to the concept of arte boludo (or ‘dumbass art’) coined by Porter and Camnitzer, as well as situating it within Porter’s wider experimentation with space and scale. The second section contextualises the work historically, reading it as a central and complex part of the New York Graphic Workshop’s aesthetic and modus operandi. The third section, written by Allen Fisher, introduces the reader to the Fluxus poet and visual artist Emmett Williams, who collaborated with Porter on Wrinkle with the writing of a mock interview that wittily ponders the difficulty of pinning down Porter’s work in accordance with any fixed genre. The fourth section develops this idea further, examining the artist’s interest in blurring pre-existing artistic categories and analysing the literary referents in her work, while the fifth section aims to make sense of Wrinkle as a critical take on existing artistic languages such as minimalism and conceptualism, as well as their political and gender ramifications.

Making Wrinkle

Born in Buenos Aires in 1941, Porter grew up in a creative family. Her father was the prolific screenwriter and filmmaker Julio Porter, while her mother wrote poems and, at a later stage of her life, also turned to the visual arts, in particular printmaking.2 Porter’s paternal grandfather had owned the Buenos Aires-based press Porter Hermanos that published, among other things, the avant-garde magazine Martín Fierro in the 1920s.3 When Porter was twelve years old she entered the Manuel Belgrano School of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires, where she received her first artistic training. In 1957 her family moved to Mexico City where the artist pursued her studies at the Universidad Iberamericana with teachers such as the Colombian surrealist painter and engraver Guillermo Silva Santamaria and the German-born Mexican painter and sculptor Mathias Goeritz. In Mexico Porter specialised in printmaking and in 1959, when she was seventeen, she had her first solo exhibition, Liliana Porter, at Mexico City’s Galería Proteo, in which she exhibited twelve oil paintings and seventeen prints.4 In 1961 she returned to Argentina to complete her training at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires, and three years later she moved to New York, where she attended printing classes at the Pratt Graphic Arts Center. A relatively early work from her New York period, Wrinkle could be seen to constitute a turning point in the artist’s practice: in it she employed the established printing methods she was trained in during her formative years, while also developing an increasingly conceptual approach to the medium’s expressive properties.

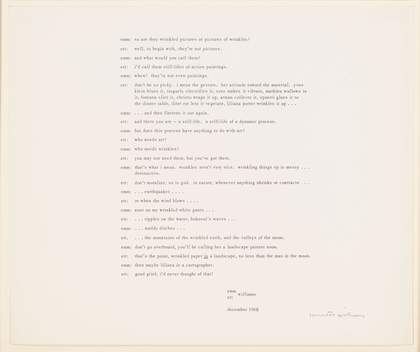

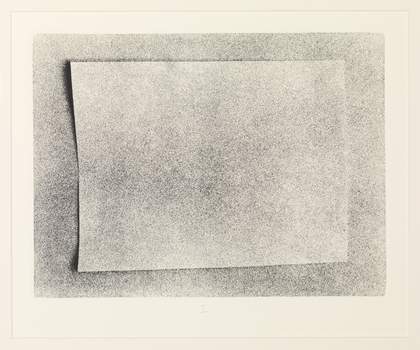

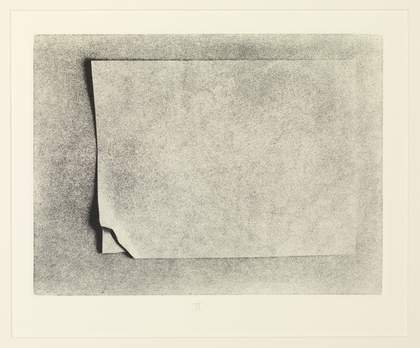

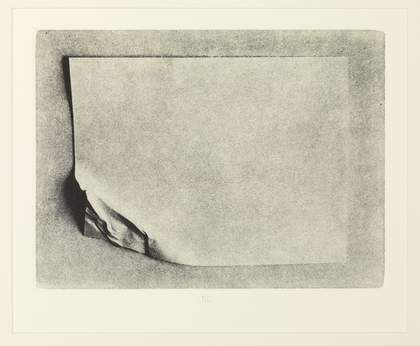

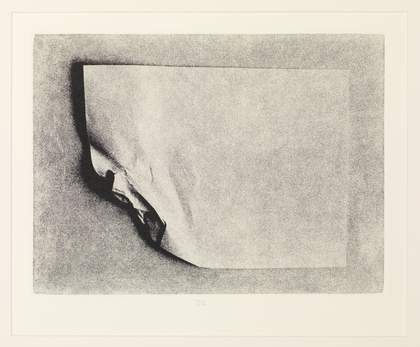

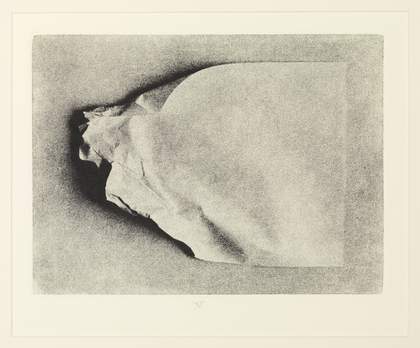

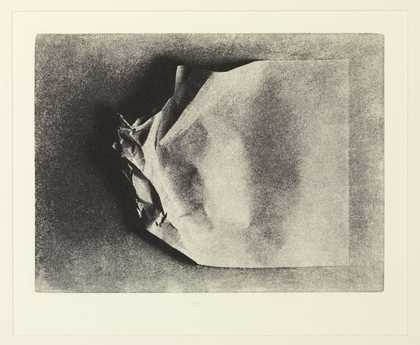

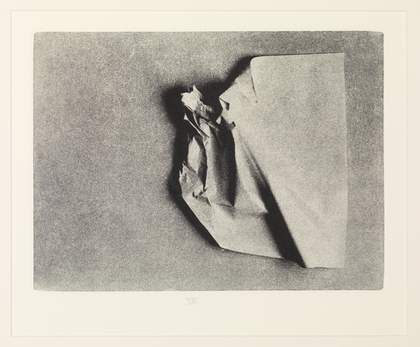

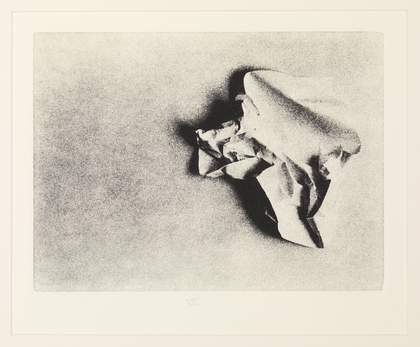

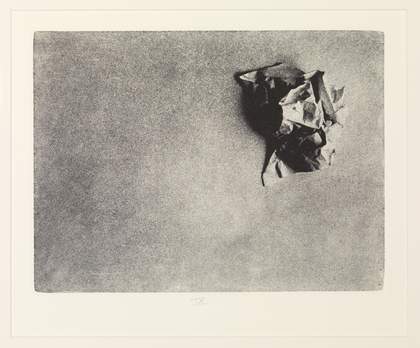

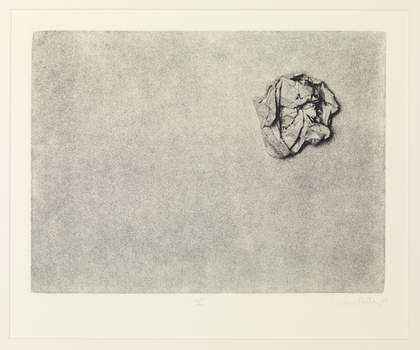

In Wrinkle, the two offset prints are presented at the beginning of the portfolio, followed by the ten black and white photo-etchings (see fig.1). The first offset print contains information regarding the name of the work and its edition number (the version owned by Tate is the artist’s proof), while the second features a text functioning as prologue to the images that follow. Written by the Fluxus poet Emmett Williams, it is an internal dialogue between two ‘halves’ of Williams (‘emm’ and ‘ett’) as they discuss the nature of Porter’s piece and the difficulty of defining it according to any established artistic category or medium. The photo-etching plates that comprise the work’s main body follow one another in a sequence, registering in grey tonalities the journey of a blank sheet of paper from an initial pristine and immaculate state to its ultimate transformation into a wrinkled piece of waste. Each plate reveals an additional stage in the crumpling of the paper according to a consecutive arrangement reminiscent of the narrative style used in strip cartoons.

The sense of rhythm that this fragmentation of the action grants to the piece is not a mere cosmetic choice: on the contrary, it is an inherent part of the work’s making process. Porter used the technique of photo-etching, a branch of printmaking that combines etching and photographic techniques. It entails exposing a photo-sensitive metal plate to an image cast negatively onto it. The image is then developed and the process subsequently stopped with a chemical bath or hot water. Once the plate has been thus etched, it can be inked – with black ink in the case of Wrinkle – and reproduced multiple times with the use of a printing press. To produce her sequential crumpling of the piece of paper, Porter had to take a photograph of each step of the action in order to create ten separate plates, making sure that the light exposure and developing conditions remained the same to guarantee a consistent effect throughout the series.5 In the display instructions she communicated to Tate in 2007, the artist expressed her wish that all twelve plates always be exhibited together, including the title page and Williams’s interview. She suggested that they are shown in one horizontal line, or arranged vertically in two columns, or in three columns of five, five and two (the latter being the two text plates).6 These display preferences expressed by the artist place an emphasis on rhythmic arrangement that matches the dynamic action represented inside the frames: an event unfolding in space as well as in time, rather than a self-contained, immobile grid.

The work and its choice of display not only create a dynamic effect; they also form an ensemble that reveals a layer of dark humour. Registering the consequences of an external, damaging intervention on the paper, the narrative shifts the sense of agency from the intervening yet invisible hand to the piece of paper itself. The paper becomes the action’s main protagonist: a tragic anti-hero of sorts, embarking on its own self-destructive path. There is something terribly mundane or banal in the action recorded by Porter. In its recording impulse, the work turns into an absurd do-it-yourself handbook for generating waste in its most common form: one of the myriad crumpled balls that pile up in office wastebaskets on any given workday. At the same time, the minute attention that the artist pays to the transformation affecting the piece of paper – observing, recording and sequencing the process – grants it a gravitas and solemnity that ask the viewer to look twice.

The art of saying nothing

This appeal to the viewer to pay attention might be one of the most striking aspects of Porter’s art practice. It is an attitude that combines ethical and aesthetic concerns, a sense of care for both the integrity of the material support and its final form. The art critic and curator Gregory Volk remarked on this when he wrote:

A crumpled sheet of paper, of course, is about as banal as you can get, and happens all the time. However, painstakingly preserving, recording, and transforming this throwaway thing is another matter entirely. In Porter’s prints, destruction shades into supple beauty.7

This interest in the minor and apparently trivial quality of everyday events has long been a defining trait of Porter’s work. During her years of collaboration with Luis Camnitzer, the two of them coined the term arte boludo, or ‘dumbass art’, to describe this approach to art making. ‘Boludo’ is a characteristically Argentine expression that points to a tongue-in-cheek attitude, combining devil-may-care and self-derogatory traits. Porter herself has defined arte boludo with the following formula:

You pick things that mean nothing (which we know is impossible) and opt for the least mysterious elements in the world, even though in fact they end up being mysterious. Look for the most neutral, least expressive things: a little hook, a shadow, a tiny thread…8

As an attitude that seeks to cast light on an irrelevant action performed by an insignificant and inexpressive object, arte boludo could very convincingly use the adventures of the gradually creasing piece of paper recorded in Wrinkle as its visual manifesto. At the same time, Porter’s own definition of the term reveals the ways in which things are never quite straightforward. As she writes, we know it is impossible to pick an object the meaninglessness of which is absolute. Similarly, the least mysterious elements in the world ‘end up being mysterious’. In Wrinkle, while the choice of a piece of paper as its main protagonist might initially be explained by arte boludo’s self-derisive attitude, combined with an ambition to undo the charismatic aura in which contemporary artists so often wrap their production and themselves, it is ultimately impossible for the work to escape the imperative of relevance.

Camnitzer expanded on this definition of arte boludo in a text written in 2006, insisting on the critical and even political ramifications of the term. As he writes, ‘I would say that the principal quality of a good arte boludo is the non-emission – or, at least, the minimum emission – of information. The work must have an undeniable presence, even aggressive at times, but it should not say anything’.9 For Camnitzer, the work should not be ‘declarative’: it should not contain any explicit message. In practice Camnitzer presents arte boludo as a research tool to formulate the minimal properties necessary to qualify a work as art: ‘It requires a formalist instinct that will help do away with the form; a conceptualism void of concept; and the skilled craftsmanship to self-erase to a carefully defined minimum’.10 The purpose of this absence of declaration lies in Camnitzer’s ambition to attack the hegemony that artists traditionally claim over the message or meaning in their works and, similarly, to criticise the passive and receptive attitude that is expected from the audience. Such an approach placed his ideas in the tradition of institutional critique that started gaining traction in the 1960s.11 Moreover, with arte boludo, the denial of obvious meaning not only critiques the tendency developed by institutions and the art market to turn works into objects of quick aesthetic consumption; it also opens the door to a more participatory attitude on the part of the public. Faced with the silence of the artwork, visitors can project their own thoughts and affects onto it, turning the work into an echo chamber for their minds. In this sense, arte boludo also opens up the work to a plurality of provisional interpretations, being born anew with each spectator. This posture constitutes as much an attack on established conceptions of artistic authorship and institutions as it does a poetic proposal to reconsider the process of art making.

At the same time, by challenging the self-enclosed nature of the artwork and the idea that its meaning is pre-established or given, arte boludo also seeks to desacralise the artistic process itself. This last point is especially relevant here as it resonates with a central aspect of Wrinkle. The modernist paradigm in art has often resorted to the alchemic metaphor of transubstantiation to illustrate the process of art making, depicting it as a mysterious practice, a quasi-magical transformation of matter taking place inside the crucible and under the watchful eye of the artist.12 This spiritual and transcendental reading of art is an important factor in the increasing canonisation of artists and the sacralisation of museums. Wrinkle, while not stating anything that is explicitly critical of this posture, works towards deriding it, revealing the open-ended nature of the artistic gesture as the formulation of questions, much more than the affirmation of an absolute answer. At the same time, however, Wrinkle is not a parody. Rather, it works towards a formulation of art as the contemplative study of a non-utterance, the absence of definition that, in its encounter with the audience, also becomes a pregnant silence. ‘A successful arte boludo’, Porter said, ‘would be capable of such perfect silence that it would, in a utopian way, allow us to listen. Boludo is the space of the opposite’.13

There is, therefore, an existential dimension to arte boludo, an aspect that also comes through in Porter’s use of space and scale in Wrinkle. Here the homogeneous format of each etching emphasises the material degradation that befalls the piece of paper, a progressive disappearance that, for all its apparent irrelevance, is also dramatic. It is the anticipation of an unstoppable loss which, while starting with a minute, minor intervention in a corner of the page, inevitably reaches a dramatic scale when it comes to affect the entire piece of paper, impacting its material integrity: its appearance, texture and volume. Small and trivial things are not isolated, Porter seems to suggest. They are intricately linked by a causal chain to large-scale events; they constitute, through an accumulative logic, those events’ foundations. As such, by beholding the destruction of a minor object like a piece of paper, it is the archetypal experience of destruction itself that one witnesses.

Space and scale

Fig.2

Liliana Porter

Forced Labor 2004

Figurine on wooden shelf and dust

267 x 1130 x 152 mm

Tate T14460

© Liliana Porter

During her career Porter would frequently resort to visual ‘tricks’, using scale in particular to make minor actions take on monumental and often symbolic dimensions. Her ongoing series Forced Labor 2004–, for instance, consists of installations in which small figurines find themselves faced with tasks that are literally greater than them. In Forced Labor (Man with Hammer) 2006 (collection of the artist), the miniature figure of a man armed with a hammer is placed on a shelf, next to a hole that has been drilled directly into the wall. The contrast between the size of the figurine, the much larger size of the hole and the white expanse of the gallery wall in which the perforation took place seems to involve the small figurine in a tragicomically Herculean task. Similarly, for Forced Labor 2004 (fig.2), Porter positions on a white plinth the small figurine of a middle-aged woman wearing a white wrap on her head and armed with a broom. Facing her, a long trail of grey sand or ash expands across the immaculate surface of the plinth. Focused on her work, the woman does not seem aware of the endless nature of the task awaiting her, as the trail progressively widens to finally end in a mound of the substance placed at the very opposite end of the plinth. The play on visual illusion by means of scale deployed by Porter in these later works grants them a wider significance, turning them into metaphorical comments on the absurdity and pointlessness of much human activity.

Porter herself seems to confirm this existential interpretation of her installations in stating that ‘[w]ith respect to the scale of the object in relation to its space, the smallness serves to underscore the infinite nature of the “place” and the “aloneness” of any entity or person’.14 Firmly set in their material rigidity, Porter’s cast metal figurines are thus transformed into symbols of resolve and persistence, set upon fulfilling their daily duties no matter how disproportionate they may seem in relation to their bodies. In their ability to grant an archetypal dimension to the mundane, both of these Forced Labor works share with Wrinkle an interest in searching for the place where meaning emerges in art objects. While initially appearing to say very little – even proudly manifesting their ambition to say nothing of interest – these works nonetheless reveal in their minute registering of daily materiality a concealed zone where so many symbolic and moral meanings take shape, questioning themselves and their audience alike.

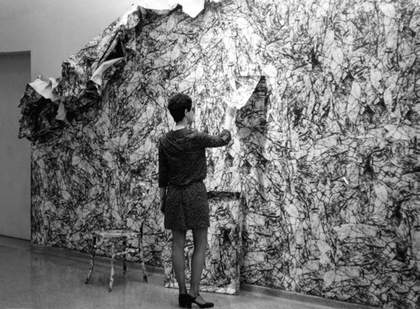

Fig.3

Liliana Porter

Development of a Wrinkle 1969

Installation view at the Museo de Bellas Artes, Santiago, 1969

© Liliana Porter. Courtesy the artist

Fig.4

Liliana Porter

Wall II 1969

Installation view at the Museo de Bellas Artes, Caracas, 1969

© Liliana Porter. Courtesy the artist

The motif of the wrinkle is not unique to this specific work by Porter. In 1969, the year after the production of Wrinkle, Porter returned to it on numerous occasions. In the exhibitions New York Graphic Workshop: Luis Camnitzer – Liliana Porter at the Museo de Bellas Artes in Santiago and New York Graphic Workshop: Luis Camnitzer, José Guillermo Castillo, Liliana Porter at the Museo de Bellas Artes, Caracas, Porter deployed her wrinkles in three-dimensional installations, or ‘Environments’, as she has often called them. In Santiago Porter showed Development of a Wrinkle 1969, a work made out of two pads of paper printed with the reproduction of a wrinkle, which were affixed on the wall and from which visitors were invited to rip a sheet and discard it on the floor, thus progressively creating a mound of torn and crumpled waste (fig.3). In Caracas Porter installed Wall II 1969, in which the wrinkle motif acquired a more theatrical inflection: the artist covered one entire wall of the room and all its accompanying furniture with grey offset paper (fig.4). The wrinkle was present in three instances here: as a motif printed on the paper, in the creased and folded manner in which the paper was attached to the wall, and in the pads of paper featuring reproductions of the same wrinkled motif that were also hung on the wall. As in Santiago, visitors were welcome to tear off pages from these pads, but this time they were invited to discard them in one of the three transparent receptacles situated in the centre of the room.15 The large scale of the installation, along with its textured appearance, recalled a mineral or mountainous landscape. Meanwhile, the upper extremities of the wallpaper were made to look like draperies, slowly succumbing under their own weight to reveal the white smoothness of the gallery wall beneath. This characteristic granted a strangely embodied, even epidermal effect to the wallpaper, as if it were a skin – a cosmetic veil covering the gallery’s backbone. In his research on skin, literary scholar Steven Connor describes it as the ‘the body’s face, the face of its bodiliness’ – a membrane that protects the body from external harm but that, by giving it a face, also guarantees its ability to interact with the world.16

Examining Porter’s wrinkled paper installations as epidermal surfaces reveals an additional and unexpected dimension: it is as if the wallpaper has intervened to fulfil a humanising function, giving a face to the cold organism that is the art institution. Yet it seems significant that it is not a smooth skin, but a wrinkled, textured epidermis that appears here, thus reintroducing a sense of imperfect and living corporeality amid the atemporal, pristine and supposedly universal temple to art that is the museum. This reading is certainly not coincidental, for it also corresponds to a critical discourse regarding art institutions and the financialisation of art that appeared in numerous works by Porter. As will be shown elsewhere in this In Focus, this took place as part of both her personal and her collaborative productions, particularly during the years of her involvement in the New York Graphic Workshop.17