Shilpa Gupta’s multi-part net art work Blessed Bandwidth consists of a website with interactive elements and downloadable content that was online between 2003 and 2013. The work addresses issues related to state control and religion. It has been described by Gupta as a ‘space which considers what is indeed “real” against the background of growing up in a place torn apart by riots on the basis of which god you worship’.1 The website provided users with the chance to receive a ‘blessing’ via a network cable which the artist had taken to religious leaders and places of worship to be blessed. The work is not currently accessible online but it has been partially captured by the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine.2

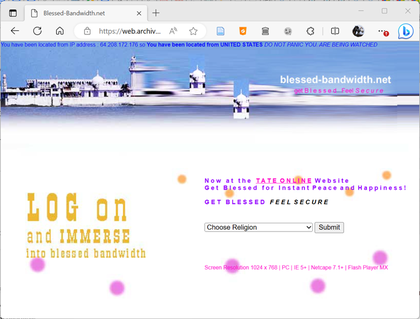

The website could be accessed via Tate’s net art pages and later its replacement Intermedia Art pages.3 On launching the site, text at the top of the page would show the user’s IP address, stating their location alongside a warning message: ‘You have been located from IP address : 64.208.172.176 so. You have been located from UNITED STATES. DO NOT PANIC YOU. [sic] ARE BEING WATCHED’ (fig.1).

Fig.1

Blessed Bandwidth homepage, featuring a message stating the IP address being used to access the site, its geographical location and the sentence ‘DO NOT PANIC YOU. [sic] ARE BEING WATCHED’.

Accessed via the Wayback Machine, capture taken 15 January 2008, https://web.archive.org/web/20080115065414/http://www.blessed-bandwidth.net/index.php.

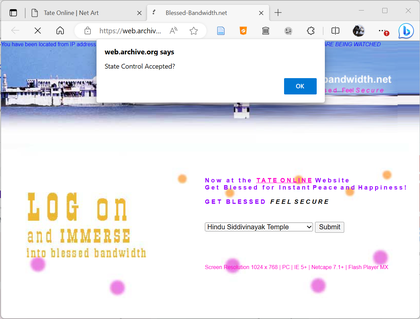

Fig.2

Blessed Bandwidth homepage, with a pop-up box prompt asking ‘web.archive.org says State Control Accepted?’ with an ‘OK’ button. The pop-up refers to ‘web.archive.org’ because this was accessed via the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine; originally this would have been the URL of the server hosting the artwork.

The sense of unease this message instils is furthered by a pop-up box asking to confirm that State Control is accepted (fig.2), and echoed throughout the website by multiple appearances of Gupta dressed as a hooded armed guard, holding a rifle, there ‘for the user’s security’.4 The homepage invites the user to ‘log on and immerse into blessed bandwidth’, to ‘Get Blessed – Feel Secure’. To log in, a user would select the religious building in Mumbai or the individual by which they wished to be blessed from a drop-down menu: the Hindu Siddivinayak Temple; the Muslim Mausoleum of Saint Haji Ali; the Sikh Sri Dashmesh Darbar; the Christian Saint Michael’s Church; the spiritual leader Sri Sri Ravi Shankar Guruji at the Guruji’s Ashram; or the Buddhist Worli Temple.

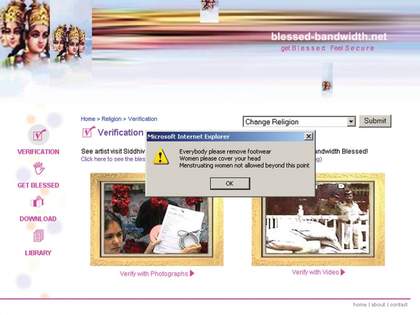

Fig.3

Screenshot of the verification page of Blessed Bandwidth 2003, by Shilpa Gupta.

After making their selection, the user would be directed to a page containing further information about the source of the blessing. The user was then guided to either ‘Get blessed’ or ‘Verification’. On both pages, guidelines on appropriate dress and behaviour appeared in dialogue boxes with warning symbols (fig.3). ‘Verification’ allowed the user to verify the authenticity of the blessing with images and videos of the network cable being blessed in the visitor’s chosen place of worship. Selecting ‘Get blessed’ took the user through to the blessing, where they were given on-screen instructions such as ‘Sit straight. Don’t lean’ and ‘Now touch your forehead to the computer screen on the Spot X’. The user could then download a certificate of the blessing, with the option to choose from a selection of borders and fonts.

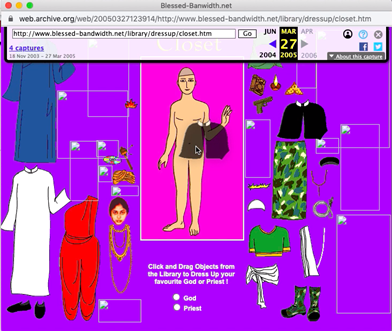

Fig.4

Archived version of the ‘Closet’ page. The broken image icons reflect the limitations of web archiving at the time of the capture, in 2005.

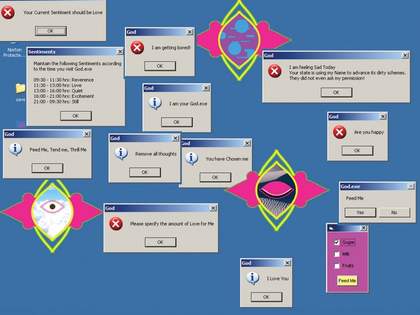

Other forms of interaction found on the ‘Library’ section of the site included the option to dress up your chosen god or priest. A pop-up window would appear and you could drag and drop images of clothing and accessories onto a figure in the centre. You could also upload photographs of your own god or shrine and write about ‘what god does to you’, listing the rules you like and the rules you break in the ‘Rules Desk’. In the ‘Download’ section of the website, accessible via a menu on the left-hand side of the page, the user could find three other forms of interaction: ‘Holy Watermarks – Download Wallpapers of Water from Holy River of your choice’; ‘Confession Diary – Keep track of your Sins, Confess them and also… Punish Thyself to find freedom from all Guilt’; and ‘God.exe – Feed me, Thrill me, Love Me, I am your God.exe and I will love you back’.

Fig.5

Screenshot of a computer home screen covered with pop-up windows launched by God.exe, a program that could be downloaded from the Blessed Bandwidth website.

Gupta created the downloadable ‘God.exe’ application with programmer [name], as a component of Blessed Bandwidth that would change as it lived on your computer. As Gupta has explained:

It comes and lives on your machine for fifteen days. It’s God.exe, then it reincarnates, God1 becomes God2 and then one becomes jealous of the other and you then, in the end, delete it. And while it’s in your computer it tells you all kinds of instructions: feed me, love me and click here, it opens your CD tracer. It sort of behaves and misbehaves and becomes more and more demanding as it goes in those fifteen days.5

When gathering the material for the ‘Verification’ section of the website – the documentary photos and videos of the artist having the internet cable blessed at each site – Gupta took inspiration from the Hindu idea of yatra, a general term for journeys or processions to sites of pilgrimage. On the website, she describes visiting each temple ‘with an Internet Network Cable and Request for blessings to bring peace and happiness to the one who comes in contact with the Specific Bandwidth’.6

The appearance of the homepage was informed by the location from which a user accessed the site. Gupta wrote in her proposal that the website would have a different homepage ‘according to zones created on the basis of economics and ethnicity’.7 It was designed so that the non-dominant religion in the user’s location would appear on the homepage; for example, for a user accessing the work on a server in Mumbai, the Islamic Haji Ali Dargah mosque would appear at the top of the homepage.8

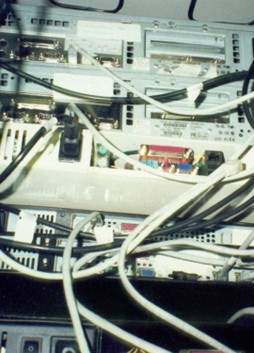

Fig.6

A photograph of the internet network cable used in Blessed Bandwidth. Before installing it in the server centre, the artist took the cable to religious leaders and places of worship to be blessed. Photograph courtesy the artist.

Reception and interpretation

For Gupta, Blessed Bandwidth relates to both the cosmopolitan dream of Mumbai and its history of religious and social conflict, particularly the sectarian riots which took place in the city and elsewhere in India in 1992, when Gupta was at art school.9 On 6 December 1992, a group of activists belonging to the Vishva Hindu Parishad and other Hindu nationalist organisations (including the Bharatiya Janata Party) demolished the Babri Masjid mosque in Ayodhya, at a site believed by some Hindus to be the birthplace of the Hindu deity Rama.10 The destruction of the mosque triggered riots all over India, during which over 2,000 people were killed, many of them Muslim.11 The effects of religious conflict, particularly Hindu nationalism, has a continuing resonance, as the critic Nancy Adajania highlighted when discussing Blessed Bandwidth in 2009: ‘Faith, even for believers in present-day India, is fraught with doubt and dilemma, shadowed by anxiety and militancy’.12

Gupta was interested in the ‘democratic’ potential of the internet and the opportunity to reach ‘wider audiences rather than just intellectuals and artists of the net art scene’.13 She wrote in her proposal for the work that it ‘hopes to open up discussions of plurality and democracy in the net art world and also more importantly function as a space for regular people to rethink issues regarding personal/others religion, beliefs, ethnicity which have thrown the world into deep friction and constant conflict’.14 In an interview with Amrita Gupta Singh in 2007, Gupta recounts the success of Blessed Bandwidth in reaching a non-art or ‘regular’ audience:

I found the website on the homepage of Christian Post newspaper based in Pakistan, from where many visitors came, or had 409 clicks from a blog run by teenagers from a website called Portal of Evil discussed how God looked like – many having downloaded God.exe – this I think is [the] most interesting part for me – which is to get a wider audience where participation and interaction is part of experiencing the work.15

The launch of Blessed Bandwidth was covered in both the Indian and British national press.16 Two articles were commissioned by Tate to appear alongside the work on Tate’s website. Heidi Reitmeier, an Education Curator at Tate who worked closely with Gupta on the commission, emphasised the critical aspect of the work: ‘as a politically engaged piece of art, blessed-bandwidth.net is something that facilitates a process of questioning. For those concerned with the ever-changing landscape of globalisation, it provokes a new form of critical awakening’.17 In the other commissioned article, art historian and curator Johan Pijnappel drew on the political context of the work to explore how Gupta plays on the notion of authenticity in religion, the art world and online: ‘For Gupta, the emphasis on uniqueness and newness in the art world is tantamount to consumerism… She takes an existing visual vocabulary, gives it a twist and creates a new narrative and experience for the visitor to the site’.18

The artist’s practice

Blessed Bandwidth is an example of Gupta’s interest in the casual encounter with sacred spaces, and forms part of her ‘Blessed’ series of works, which concerns the display or encounter of ‘blessed objects’.19 The first work in the series, Blessed Canvases 2002 (figs.7 and 8), is an installation of small canvases created by Gupta and blessed by forty famous holy persons and places of worship.20 The second, Museum 2002, comprised 1,500 objects crocheted by women in India, which Gupta then had ‘blessed in a Hindu place, at a temple or at a mosque or at a church’.21 The two artworks were shown in the exhibition New Indian Art: Home, Street, Shrine, Bazaar, Museum at Manchester Art Gallery in 2002, curated by Gulam Mohammed Sheikh and Jyotindra Jain. Blessed Bandwidth expands on these ideas of distributive blessings.

Fig.7

Still from the video element of Blessed Canvases 2002, by Shilpa Gupta. Image courtesy the artist.

Fig.9

Installation view of Blessed Canvases 2002, by Shilpa Gupta. Photograph courtesy the artist.

Gupta’s practice explores notions of location and belonging both against and within the complexities of national identities. She is interested in the ‘imagination of the democratic’,22 taking a research-based approach to film, sculpture, installation, the web and performance. For Gupta, ‘the idea of making things more distributive’, in terms of how the work is made and encountered, and who has access to it, is central to her work. As Adajania has described, ‘her real and primary medium is audience perception. By provoking and probing her viewers’ reactions, by developing approximations of public feeling and conventional wisdom, Gupta investigates the micro-politics of a society’.23

While studying sculpture at the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art in Mumbai from 1992 to 1997, Gupta enrolled in a series of courses on computer programming, including in 3D animation, Photoshop and Dreamweaver. Despite her work as a programmer and web designer in Mumbai, Gupta has never been interested in technology for its own sake, but rather in its portability, accessibility and its potential for art or democracy: ‘I’m not interested in tech because it’s tech. I’m interested in its possibilities – it’s a medium.’24

Gupta’s first online artwork, Diamonds and You 2000, was made on the web hosting service GeoCities.25 Within its pages, the user could select a diamond they wanted to purchase and discover the economic and political effects of their choice. Her website Sentiment Express 2001 – developed for the exhibition Century City: Art and Culture in the Modern Metropolis which took place at Tate Modern the same year – offered a sentimental letter-writing service: ‘Just speak your emotions into the microphone and the rest will be taken care of. Your letter will be handwritten, scented and mailed to the person of your choice. It will be processed in Bombay, which has 16 million people and a lot of unemployment, so lots of cheap skilled labour to do work such as this.’26 For those with less time, there was the convenient option to produce and download a standard love letter.

Technical narrative

Blessed Bandwidth incorporates many components into a single artwork: a multi-page website with interactive elements, downloadable content including a windows executable program and a blessed network cable located in a server centre, which connected the artwork’s server to the internet. Gupta designed the front end of the work’s website, including the visuals, using the web development program Dreamweaver, which she continued to use in her work until at least 2020.27 Some of the backend functionality, the God.exe application and some of the Adobe Flash Player (Flash) elements were implemented with the assistance of programmer friends, with whom she had previously collaborated to create the work Sentiment Express.28

Initially the work was accessed via an external link from the Net Art pages on the Tate website at the URL www.blessed-bandwidth.net. In 2008 it was included in the Intermedia Art pages, with the other net art commissions. Gupta took out a ten-year lease on the website for the work, not wanting it to sit on Tate’s servers, but to be ‘an independent thing’.29 The separation from Tate’s server also allowed her to alter and adapt the work. The site used technologies and standards typical for the period, including Flash elements, and a design optimised for a screen resolution of 1024x768.

Current condition

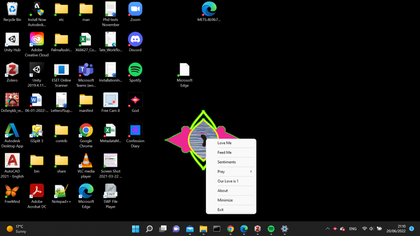

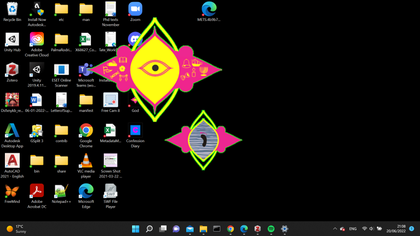

The website blessedbandwith.net is no longer online, but there are a series of web captures on the Internet Archive, which although only partially functional allow us to understand how the site looked and behaved at the time. Surprisingly, God.exe could still be downloaded from the archived site, and we were able to run it on a Windows 10 laptop, with its functionality apparently only slightly affected (figs.10 and 11). Simpler downloadable elements, such as the Holy Watermarks, which were meant to be downloaded and printed, have not been recorded.

Fig.10

Main menu for God.exe, running on a Windows 10 laptop

Fig.11

God.exe on ‘prayer mode’, running on a Windows 10 laptop

Blessed Bandwidth has been shown in different ways since it was commissioned by Tate, including as a projection in an exhibition, suggesting there has been some flexibility in the way the work can be experienced. We discussed several potential forms the work could take, from rebuilding the website to using images and other static elements of the work as documentation that could be presented in an exhibition. Gupta proposed testing different exhibition formats with the public:

Do I imagine Blessed Bandwidth could go up on the internet and exist? Yes, sure, it’s something to try out and see how people experience and imagine it now. We’ll have to let it play; you have to see it. I mean, do I want it to live? I think let’s put it up over the internet, let twenty people look at it or 100 people look at it, then let’s decide whether you want to put it up or not. Let’s get feedback from them how they imagine it to be.30

From our conversation with Gupta, we learned that she had built an offline version of the site to show people who came to her studio. Using these materials, it may be possible to rebuild the site and possibly update some of the interactive elements.

Reviving the work would need engagement from the artist, and from Tate if it were to add it to the collection and support it in the long term. It is difficult to assess the risks for preservation involved in running the backend of the site, so a combined approach of code intervention and emulation might be necessary to ensure the functionality of Flash elements, as well as to meet the security standards of current browsers, which can block HTML that is no longer supported.

In the ‘Library’ section of the website, the two user interfaces – allowing visitors to write about rules they like or dislike, share comments about ‘What god does to you’ and upload images – would require careful consideration. The host would need to consider issues of data protection and content moderation when re-activating these functions and create a policy for how inputs are stored. They could be deleted, archived offline, made visible on the website or even displayed offline; Gupta mentions previously printing and displaying some of the submissions.30

Conclusion

Blessed Bandwidth shares some similar thematic concerns and technical setups with other works commissioned for Tate’s net art programme. Its simple functionality and invitation to users to participate, through downloading and printing out elements, for example, is reminiscent of Heath Bunting’s BorderXing Guide project, which is similarly instructional, and Susan Collins’s Tate in Space, which invited users to submit designs for a satellite gallery.31 All three works consider how networked space can be an extension of our lived experience of the world, and the potential for computers and new technologies to enhance our experience of life in both practical and symbolic ways. But what information do we have to offer in return, and how is that data stored? What control do we have over our experience of being online?

Made in 2003, Blessed Bandwidth can be located in the context of other art projects that asked what good being online could do for us, and whether we should be worried about the potential surveillance opportunities that enhanced networked computing offered. The God.exe program of Blessed Bandwidth, for instance, bears some similarity to Thomson & Craighead’s 2001 net art work e-poltergeist, which lived in your browser and activated search queries without permission (e-poltergeist had no escape and you had to force-quit the browser to get back to the web searches of your own choosing).32 If being online is an extension of our experience of the world, both e-poltergeist and Blessed Bandwidth question who we are sharing that virtual space with, and what kind of community of belief we might find ourselves in.

Like some of Gupta’s earlier artworks, including the love-letter writing platform Sentiment Express, Blessed Bandwidth addresses the division of labour between human and machine. Similar concerns were addressed a few years later by artists Ute Hörner and Mathias Antlfinger in their online project Non Chat Chat – Meditation for Avatars 2006. Users could sign up to have their computer’s network downtime be repurposed for chanting, spreading good karma to other computers around the net.33 The launch of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk program in 2005 resulted in a number of net art works in which small repetitive actions were made routine or outsourced to gig economy workers. The seemingly altruistic gesture of listening to your confession, being blessed or having someone take the time to chant so you don’t have to (and can keep on working), masks the potentially lucrative transfer of personal information, including access to your computer’s own networked connection, to another server. It seems ironic, therefore, that in order to restage this work we would need to rely on the network’s own decentralised record keeping of it: the bits and pieces that could be found in the Internet Archive, in the artists’ own archives or in archives of users who downloaded from it. Much like wishes or prayers, spoken into the ether, these would have to be reassembled and pieced back together manually through communal effort, not automatically by some selfless, technologised God.exe.