Edgar Calel

Discover explorations of community and family, Indigenous technologies, and the ownership of art

Here I’m stretched out, resting for a moment on the land, all tiredness is freed from my body. Soon I’ll return from my journey and where I’ll end up today is unknown.

In Indigenous Kaqchikel thought, there's almost nothing that is done alone. All the things we do are done collectively, and that collectivity is what serves as the basis for discovering. What is your function? Or what is your role within society?

Thinking about art in these territories is closely related to how life is connected to nature, to memory, and to the spirit of those who came before us. So art arises from a necessity, doesn’t it? It can be to commemorate life, and on the other hand, a commemoration of all the legacies that our ancestors left seeded to give continuity to life.

Thank you, grandma. Thank you, grandpa. For everything you have sent us. Thank you. Thank you all for your effort, for all the work, and for the times when we don't eat because of our work.

Sometimes we get angry. Sometimes we lose sleep. I consider it's an important moment to thank everyone for their effort. We also thank our grandfathers and grandmothers for the knowledge and the opportunities to create art. We make these sacrifices to the stones. We offer them fruits, incense, liquor, tobacco, words. It is in them that the ancestors come to take refuge, to have a body for us to be able to have physical contact with them. And the idea of exhibiting it [at Tate] was to deliver a message that not all things are for sale, that there are things that belong to humanity and that no one can possess it.

It seemed fair to me that the practices of the Indigenous people, even when circulating in an art market, continue to belong to them and to us. Just let us tell you that we are not selling them, but based on [Tate's] interest, we can appoint them as guardians for a certain period of time. And then being guardians of the pieces implies that they're not the owners but collaborators who contribute so that other cultures also engage in self-reflection and for the people to have a connection with their origins, with their ancestors.

When I think of an idea, sometimes it's my own desire, and I share it with my brother; we visualise things together. My brothers are other extensions of myself, and I am other extensions of them and of my parents, and my parents are extensions of other generations that have already passed away. And so we have that mission through our work. We have something to say, something to tell, and this desire to build a family history, to build a profile of our existence and our passage here on Earth, and specifically in Comalapa. So there's also this commitment to want to leave a small trace.

One of my grandmothers, the one who lived here in this house, I started writing countless memories of her. There's one that stands out a lot, which is a song she used to sing in her house. There were many fruit trees, birds, chickens. First, she would bring them corn, and then she would call them, and then she would sing like kit, kit, kit, kit, kit, kit. And she would grab a handful of corn and release it on the ground. And when all the grains stayed like a constellation, the animals would come to peck at them. And then when she died, I kept thinking that I would never hear her song again, kit, kit, kit, kit, kit, kit.

And so I thought it would be very interesting to bring out a little of that song within me. And how am I going to bring it out? So my family and I started thinking that it would be good to paint the facade of her house with mud, write the same song but with soil on the facade of her house, and that the colour of the soil would be the colour of her voice. And so there were several elements there that were shaping up until there was a piece where both the thought and its materialisation came full circle.

Return his spirit, let it not linger where his fears reside, where it is detached. May his spirit return. May his soul return. May you bestow your blessing, your grace, Divine creator. May you assist us with this outpouring of spirit. Where have you stayed, blessed creator? You who are the owner of their entire life, may their spirit return.

Every time we leave our house, there is this word in Kaqchikel: Tachajij, q'alaj xtachajij awi. If I transform this word into an image, it could sound like there you protect yourself with the essence of fire, which would be the ashes. And so when I do this performance, my dad and my mum grab a pot of ashes this size, and they place the ashes all over my body as a way to visualise how to protect yourself within the Kaqchikel language.

Art has a craft and a purpose; it benefits everyone when it brings us all to reflect, to evoke. There are two ideas that come to mind when I analyse the purpose of art: It serves to find knowledge within it, and it serves to preserve the legacies that have been passed down to us, and not everything will be unveiled.

We had the desire to have a vehicle, so when I returned from a trip to Brazil, I said, "I'm going to participate in a contest, and my goal is going to be to win." So from there, I selected four photographs, and then I said, "Well, now I'm going to print the photos." But the thing is, I also didn't have money to print the photos, so I sent the files, and they were printed there. At the award ceremony, I realised that they had given me first place, and then I said, "Well, I know what I want. With that money, I'm going to buy a car."

Art is a vehicle to carry things with a lot of responsibility, but it's also a metaphor for the vehicle because who I transport is my family; it's their thoughts and memories. And so from there came that scene of thinking about how many trips we have made together. I found it interesting to make this scene when the car breaks down and you have to push it.

There comes again the collective strength and the presence of everyone. That's why there's also a scene of the pick-up truck with the hood open. Someone wants to fix the car but there really isn't any mechanic. That gesture for me is very important because it is sometimes you turn off the car and then you turn it back on and it starts again. Sometimes life wants a break. Sometimes you have to stand there you are in that place. That's what inspires me to be grateful. Life has not denied me anything; it has given me everything with spirit and delight. And may the great grandfather open my path to do my work. And may nothing stop us from what I have started and we have started with my family. With these words, I am deeply thankful.

About the video

Encourage your students to respond to the video in their own ways – perhaps by making notes, doodles or drawings, or through gestures and sounds.

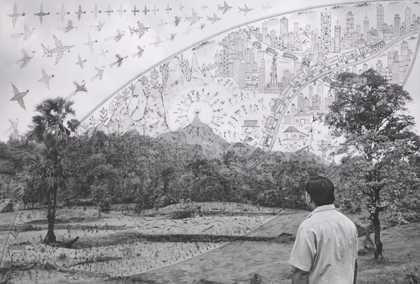

Edgar Calel makes art in community, with his family. His 2021 artwork, titled Ru k’ox k’ob’el jun ojer etemab’el (The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge) offers fruits and vegetables atop stones as a gift of thanks to the land and his ancestors. Drawing on his Kaqchikel heritage, Calel brings together dreams, nature, and memory in his artwork, creating space for Indigenous knowledges to be acknowledged and respected.

‘All the things we do are done collectively’

Edgar Calel

Discuss

Your students' ideas and experiences are the best starting point for any discussion. Using the prompts below, support meaningful and creative discussions in the classroom about the video’s key themes. Discover how Edgar Calel’s practice can inspire your students to learn with art.

Family and Community

Calel makes his artwork in community with his family, visualising things together to tell their stories. He says, 'My brothers are other extensions of myself, and I am other extensions of them and of my parents, and my parents are extensions of other generations that have already passed away.’

Prompts

- Who and what are you an extension of? You could think of family, friends, pets, or even places!

- How could you visualise these connections? Are you knots on a rope, nodes in a web, rocks sitting together on the seashore, or something else entirely?

- In pairs, share your connections together. What can you learn about someone by who and what they’re connected to?

Indigenous technologies and ritual as practice

Calel says, 'In Indigenous Kaqchikel thought, there is almost nothing that is done alone.' By offering fruits, vegetables, and other gifts to the stones, the stones become bodies for Calel’s ancestors to inhabit and take refuge in. The ceremonies and rituals that Calel performs are both an art practice and an Indigenous technology, mechanisms that show us 'how life is connected to nature, to memory and to the spirit of those who came before us'.

Prompts

- Think about any rituals or ceremonies that you take part in. These could be religious or cultural, done privately or in community, or even take place online! How would you describe and celebrate your rituals?

- If someone else wanted to celebrate you the way Calel honours his ancestors, what objects could they use to represent you?

- Think of a space, building, or region of land that you feel connected to. What stories could you tell about it?

Ownership or care?

In 2023, Tate became custodians of Calel’s work, The Echo of the Form of Ancient Knowledge. Rather than owning it, the agreement acknowledges Tate’s responsibility to protect Calel’s artwork while recognising that it goes beyond the physical form. As Calel says, 'not all things are for sale'.

Prompts

- What do you think it means to own an artwork? Can you imagine other ways of sharing art around the world?

- Imagine you became a custodian for an artwork. What would you do to look after it?

- Pick an object from your home or everyday life that represents you. Would you want a museum or gallery to look after it for you? Why, or why not?

How to use Artist Stories

Introduce art and artists into your classroom with Artist Stories resources. The resources combine engaging videos and thoughtful discussion points to encourage confidence, self-expression and critical thinking. Art is a powerful tool for discussing the big ideas that impact young people's lives today.

- Explore the video:

- Read About the video to introduce the artists to your students.

- Project the video or watch it in smaller groups.

- Each video is between 3–10 minutes.

- Transcripts are included where available

2. Discuss the video:

- Invite your students to respond to a discussion prompt individually. They could record their responses through writing, drawing, making or voice recording. (5 minutes)

- Invite your students to share their ideas and responses with someone else. What have they learned about themselves or others by sharing their responses? (5 minutes)

- Invite your class to share their thoughts and ideas in groups or as a whole class, inviting multiple perspectives and experiences. (10 minutes)