Pio Abad

Watch a video with Turner Prize nominee Pio Abad and explore colonial histories, cultural loss and the power of objects

Pio: I grew up in Manila, in the Philippines and so I was born at the tail end of the conjugal dictatorship of Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos that ruled from the late '60s to the mid-eighties.

Imelda Marcos is my muse and my monster really. She's this ghost that haunts the practice. She became incredibly well-known for her extravagance, there was the jewellery, the shoes, the real estate in New York. At some point she had the largest collection of Regency era silverware in the world.

These are legally known as the Hawaii Collection because when Ronald Reagan granted them exile in Honolulu, Imelda arrived with diamonds in diapers. She'd stashed all her jewels in her grandson’s diaper bags

There's a part of me that is drawn to the kind of visual elements that is tied to her extravagance. When you really try and unpack the fantasies that she built for herself and you kind of go back to the fantasies of capitalism and the fantasies that we are all implicated in.

My wife, Frances Wadsworth Jones who is a really brilliant jewellery designer. She plays a lot with art historical tropes in her work, really subverting the language of material. I always say I'm the project manager and she's the talent. Our shared interest in history and this kind of subversive element to our work has made it you know, the perfect collaboration.

I think we're all magpies, we’re all drawn to these shiny objects. This fascination with jewellery really is part of this larger interest in the role of seduction and its relationship to power. And in my work, you know seduction is key. You can't really get closer to the body than with jewellery. On the one hand they are these incredibly seductive, really beautiful things and these beautiful things might be vessels for painful stories.

When I think about art I think about storytelling. When I think about storytelling I immediately go to my family. My parents met as trade union organisers in the 70s, they ended up being very much involved in Philippine politics. The Philippines was so dominated by the Marcos's corruption. I think my experiences of seeing my parents struggle during the dictatorship have really shaped the way I thought.

So my aunt is the Filipino-American artist Pacita Abad. It was my aunt who was supposed to enter politics. There was this moment in the late sixties just before martial law was declared. The Abad family home was sprayed with machine-gun bullets largely because my grandfather was involved in the opposition. And my aunt at the time was a very visible student activist and that led to her leaving the country and eventually becoming an artist. And she provided that sense of possibility you know, that it was possible to become an artist.

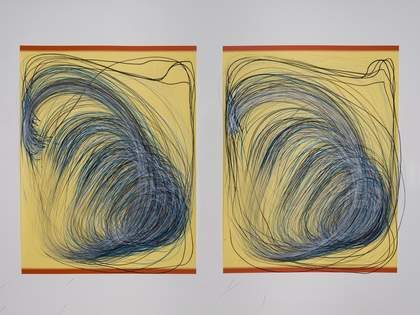

I think the role of the Philippines in my work is central. I think that's where I grew up and that's where my politics was shaped. But this idea of the Philippines as a small world that contains many things is what I've always been fascinated with. Trying to unpack complex histories of colonialism through the intimacy of the objects. This artistic process actually begins with a heavy amount of research and I think I'm happiest when I'm in the back room of a museum sifting through things or when I'm kind of given access to these private archives that have never been seen before. At the centre of it really is drawing. This act of tracing or of using the pen to translate an object but then that shoots off to text or to 3D printed sculpture or to bronze or even to augment reality.

I usually walk from home to the studio which is about a 25-minute walk. I always think it's sort of a fascinating alternative tour of south east London through the bits of the river that people don't want to talk about. I came across a small section of a book called Brutish Museums by the curator Dan Hicks and he talks about how the British army prepared for the burning and the looting of the Kingdom of Benin. All of this was happening in the Royal Arsenal stores and the hair on my arms stood up because I was in the Royal Arsenal store, my flat was the Royal Arsenal stores. These drawings really started from that kind of drawing the bronzes but kind of equating them with things that I found in the house, whether the things I valued, or domestic objects that have less than savoury histories of extraction. What I really wanted to do was to find a way of measuring these historical objects according to personal dimensions or even emotional dimensions.

I went back the other day to the British Museum just to see the original artefacts and it's almost like they've been purposefully displayed to seem less important than they are. Like with the Benin Bronzes in particular and obviously they've been at the centre of conversations surrounding the roles that museums play now and whether, you know these sites of knowledge need to be held accountable. My home played a significant role in the way they were taken from Benin and then brought to the UK. They become both universal and very, very specific.

And so these drawings kind of reflect on these objects or universal icons of cultural loss to many people, they, you know they're their lost ancestors, their histories that you can never recover.

About the video

Encourage your students to respond to the video in their own ways – perhaps by making notes, doodles or drawings, or through gestures and sounds.

In this video, Abad explores the power of storytelling through objects, such as jewellery. As he says, 'we're all magpies, drawn to these shiny objects.'

"We’re all drawn to these shiny objects"

Pio Abad

Pio Abad explores cultural loss and colonial histories through his artwork, often reflecting on his childhood in the Philippines and his parents' role in the anti-dictatorship struggle. Using drawing, etchings and sculptures, Abad highlights overlooked histories.

Discuss

Your students' ideas and experiences are the best starting point for any discussion. Using the prompts below, support meaningful and creative discussions in the classroom about the video’s key themes. Discover how Pio Abad’s practice can inspire your students to learn with art.

The Power of Objects

Familiar objects can be powerful tools to help us tell complex stories. Abad looks at historical jewellery and objects to unpack histories of colonialism, researching them to find out more about where they came from and who used to own them.

Prompts

- Think of someone in your life who wears jewellery – earrings, a bracelet, maybe a wedding ring. What does their jewellery tell you about them? What can you learn about them from the other accessories they wear?

- Are there any objects that are important to you? How would you describe these to someone else?

- Think about a moment in history that you’re interested in. How could you learn more about it through objects? What objects would you choose, and why?

Hidden Histories

Abad describes walking through South East London from his home to his studio and then learning about the history of the area. He also talks about growing up in the Philippines and how the political situation at the time affected his life.

Prompts

- How do you think histories might become hidden over time?

- What do you know about the history of the area you live in? How could you find out more?

- How would you share your own family histories with your classmates?

Making Art Today

Abad is one of four artists nominated for the 2024 Turner Prize, which celebrates the best of British art today. Though his practice, Abad brings important discussions about the impacts of colonialism and political struggle to contemporary art.

Prompts

- Contemporary art means any artwork made in the present or recent past. Can you think of any other contemporary artists you’ve heard of before? What similarities and differences can you find between them and Abad?

- What do you think artworks should say? Do they need to have an important message? Why, or why not?

- If you could interview Abad, what would you ask him? What do you want to find out about his life and his artwork?

How to use artist stories

Introduce art and artists into your classroom with Artist Stories resources. The resources combine engaging videos and thoughtful discussion points to encourage confidence, self-expression and critical thinking. Art is a powerful tool for discussing the big ideas that impact young people's lives today.

- Explore the video:

- Read About the video to introduce the artists to your students.

- Project the video or watch it in smaller groups.

- Each video is between 3–10 minutes.

- Transcripts are included where available

2. Discuss the video:

- Invite your students to respond to a discussion prompt individually. They could record their responses through writing, drawing, making or voice recording. (5 minutes)

- Invite your students to share their ideas and responses with someone else. What have they learned about themselves or others by sharing their responses? (5 minutes)

- Invite your class to share their thoughts and ideas in groups or as a whole class, inviting multiple perspectives and experiences. (10 minutes)