George Stubbs, Otho, with John Larkin up 1768. Tate.

Stubbs and Wallinger The Horse in Art

Two artists, born three centuries apart, combine anatomy and expression in their portraits of racehorses

2024 marks 300 years since the birth of the animal painter George Stubbs. Today he is celebrated as one of Britain’s greatest horse painters. This display brings together paintings by Stubbs with a contemporary horse painting by Mark Wallinger.

Stubbs’s representation of horses marked a milestone in animal and sporting painting. Rather than horses appearing as a supporting character or accessory to the sitter, he made them the focus of his paintings. Stubbs elevated animal painting in the eighteenth-century visual hierarchy of painting that privileged idealised scenes from antiquity, modern history, mythology and literature. He was devoted to understanding the physical structure of horses, from the hide to the muscles, arteries, tendons, and down to the bone. By studying the anatomy of horses, Stubbs achieved unprecedented realism in his images.

Stubbs was highly in demand as a horse painter. He was commissioned by wealthy aristocratic landowners who raced and bred horses. Stubbs’s association with social class, power and the notion of national identity has influenced Wallinger’s artistic practice. Wallinger says, ‘[Stubbs] uncovered the structures of the creatures he depicted as well as understanding the structures of power and patronage he worked with as an artist.’

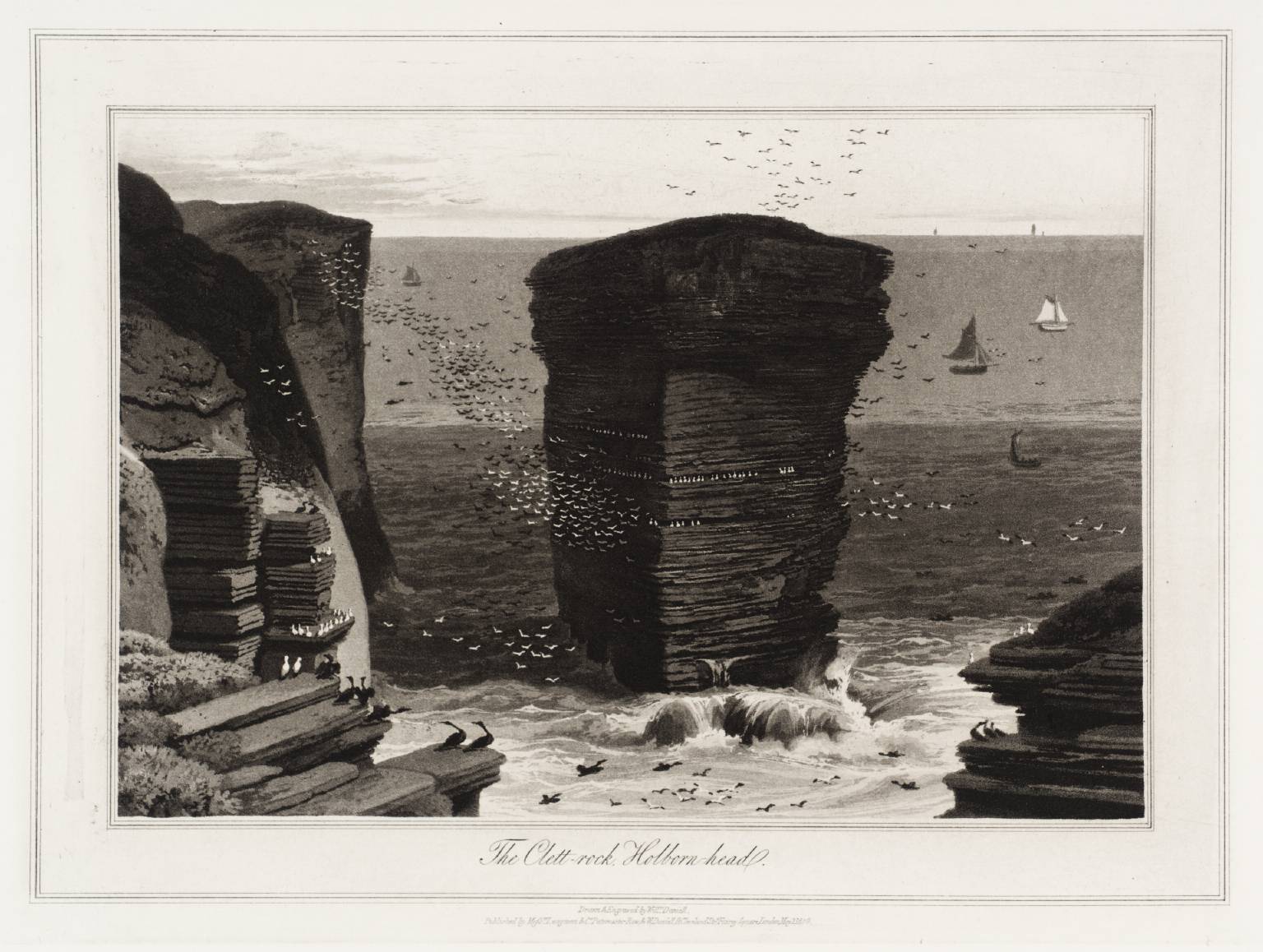

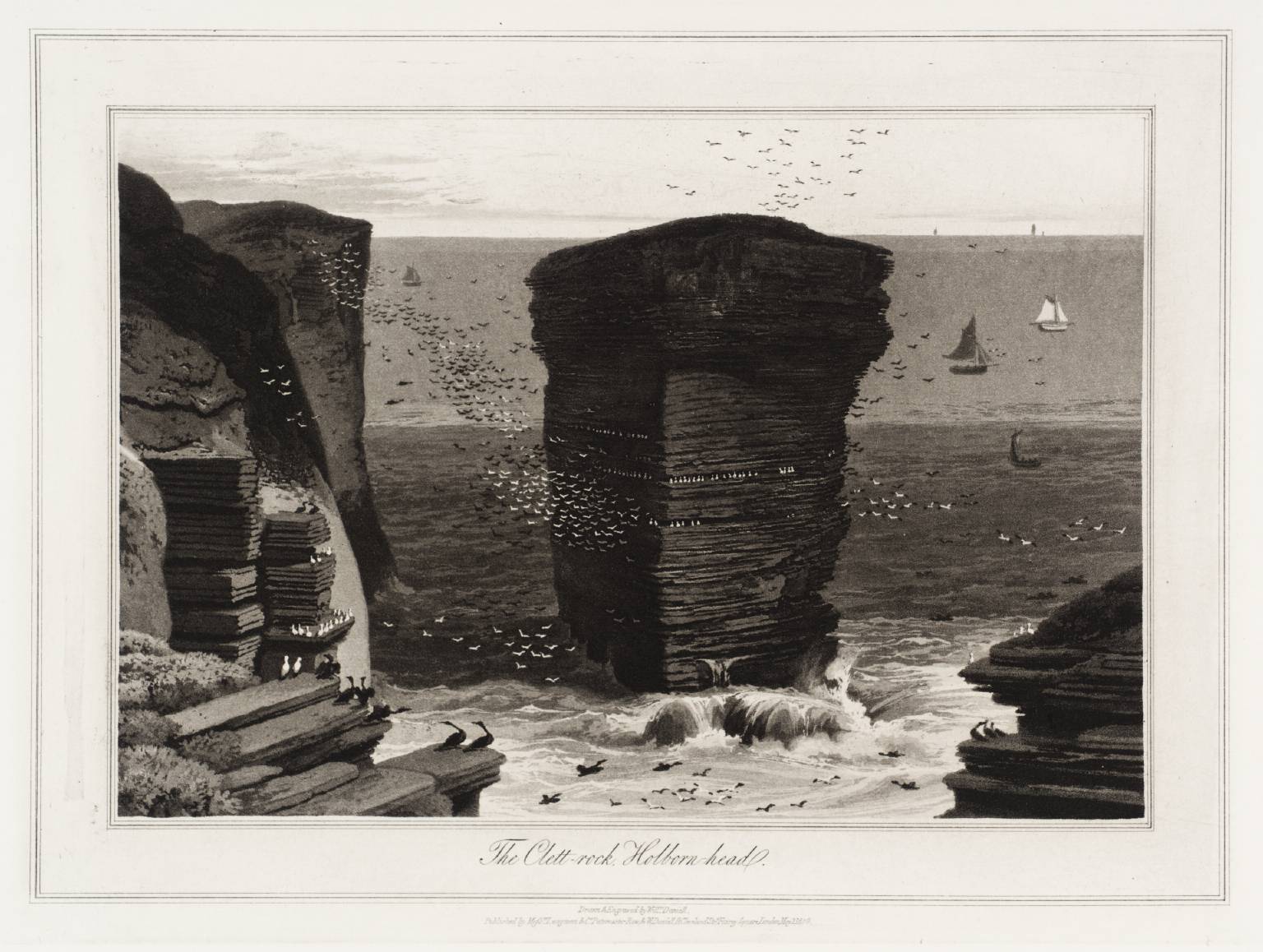

William Daniell, The Clett-rock, Holborn-head Date not known

1/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

John Wells, Sea Bird Forms 1951

2/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Don Cordery, Spectacled Owl 1973

3/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Marmaduke Cradock, A Peacock and Other Birds in a Landscape c.1700

Marmaduke Cradock was one of the few British-born painters of birds and animals active in the late-17th century. This composition of turkeys, rock doves, a peacock and a jay shows the artist’s careful observation of birds. The calm of the dovecote is disturbed by the danger of a predatory fox. However, the central focus of the painting is the peacock, a rare bird which Cradock could have been observed in London’s royal parks. Its rich and colourful plumage speaks of wealth and opulence.

Gallery label, July 2024

4/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

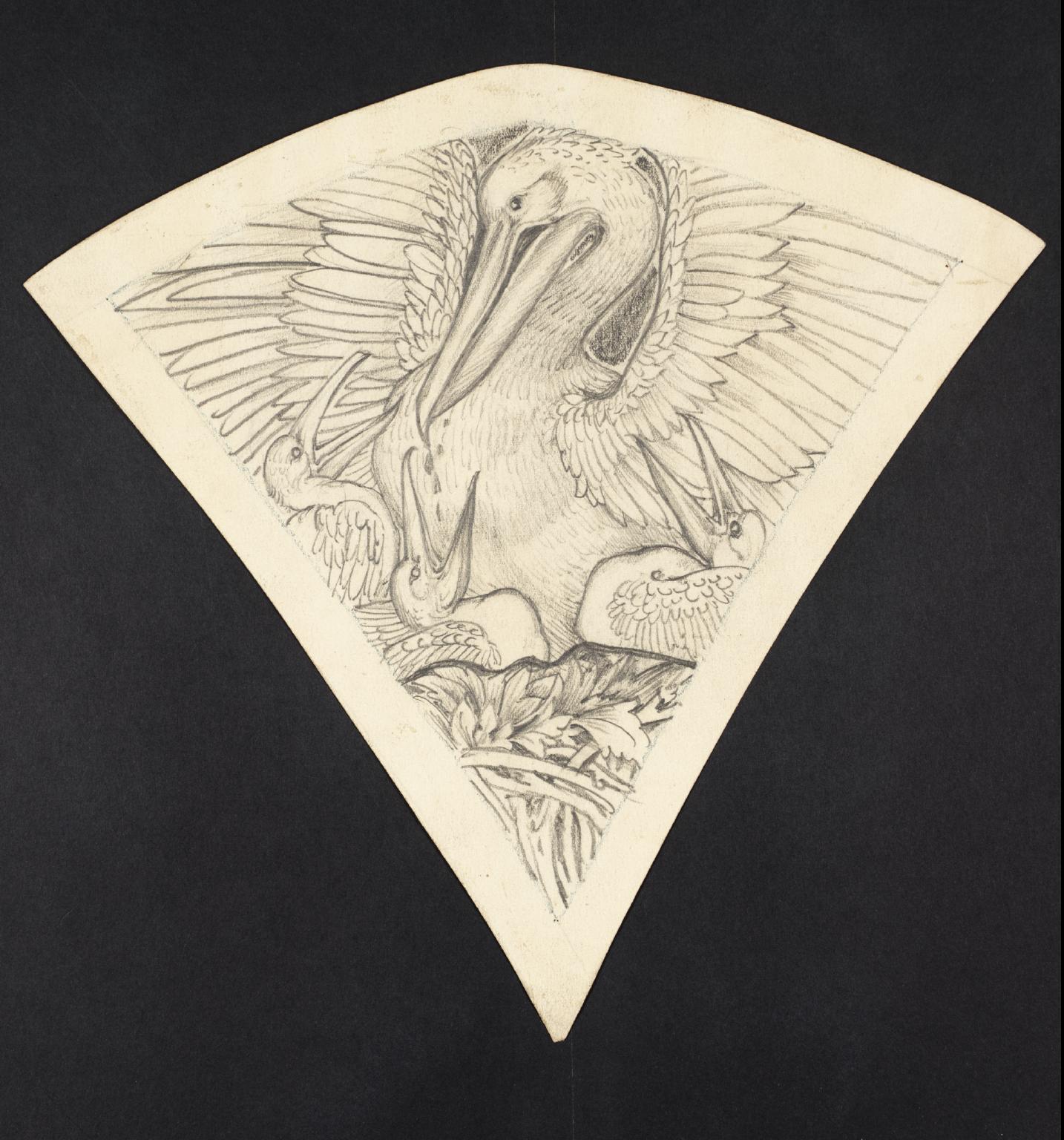

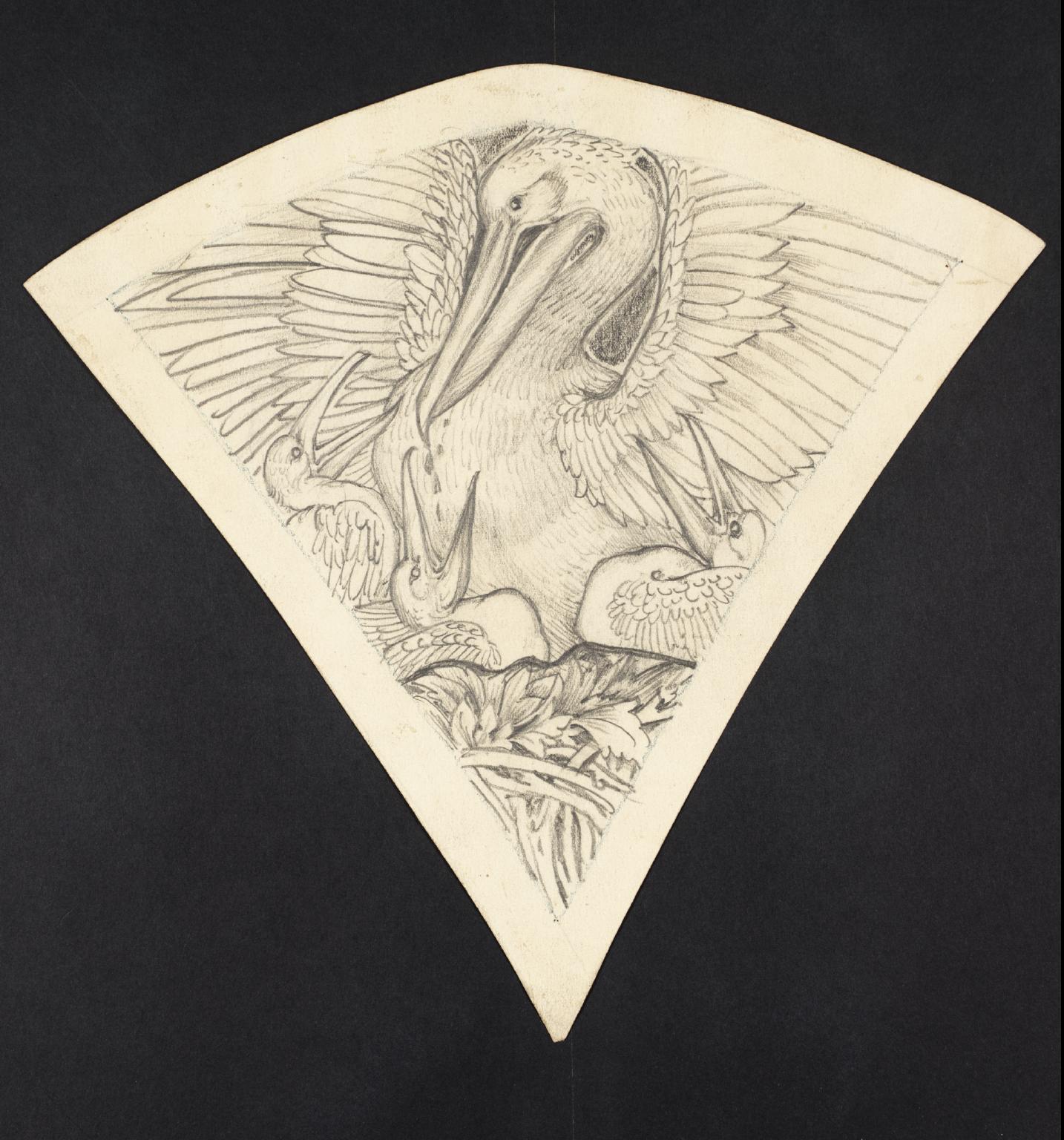

Philip Webb, Study for Heraldic Glass 1893

5/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

William Henry Hunt, Primroses and Bird’s Nest Date not known

From 1851 until his death in 1864, Hunt exhibited an annual average of eight works. Fruit, bird’s nests and flower subjects were in the majority, probably because they were the most financially successful. Hunt became as popular in this field as he had been with his earlier, humorous drawings of boy models.

In October 1863 Hunt wrote to a friend: ‘I was in hopes of trying my hand at figures, but have so many persons’ promises to do fruit and flowers for them that I can get no time to do anything else.’

Gallery label, September 2004

6/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

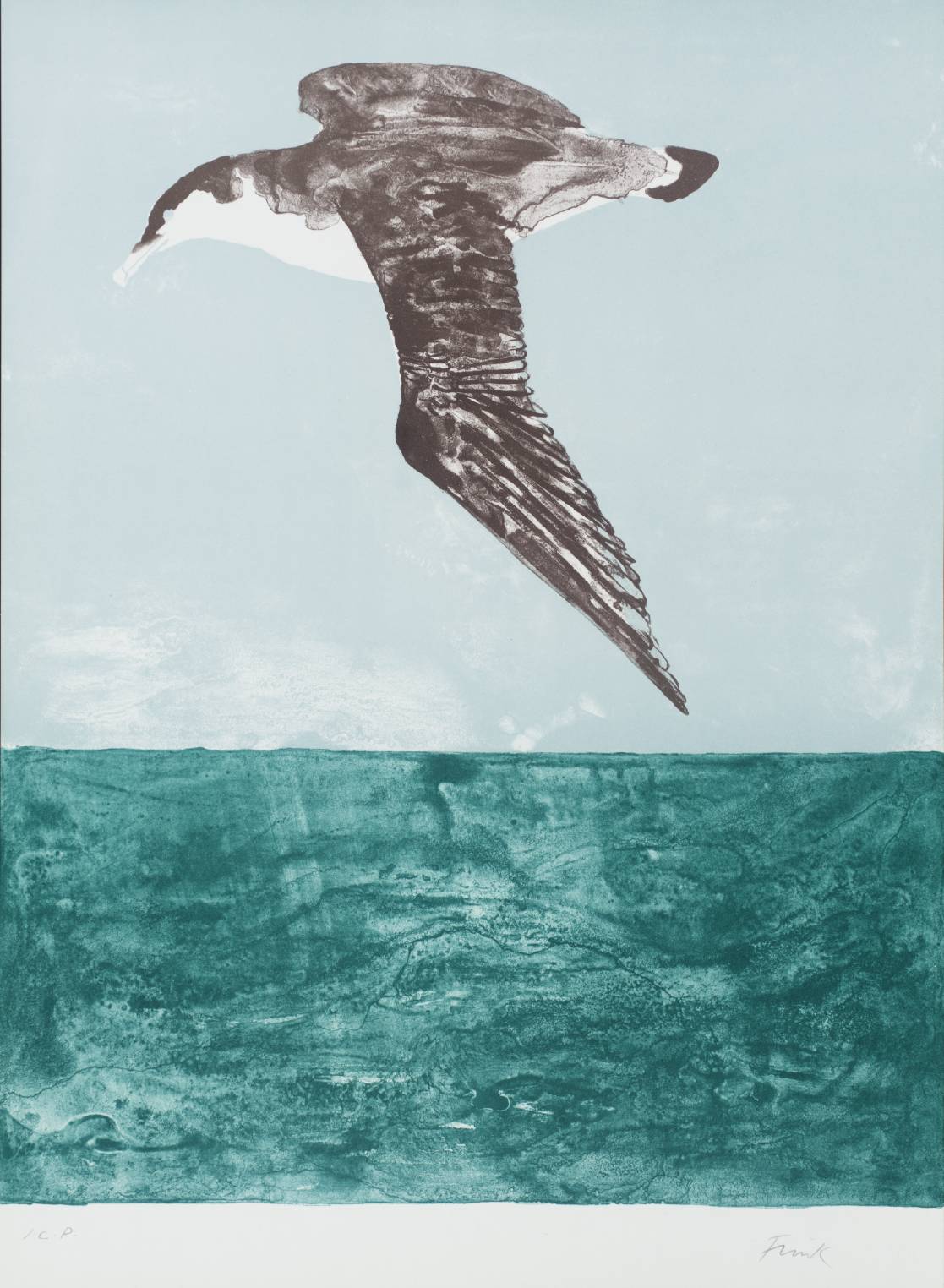

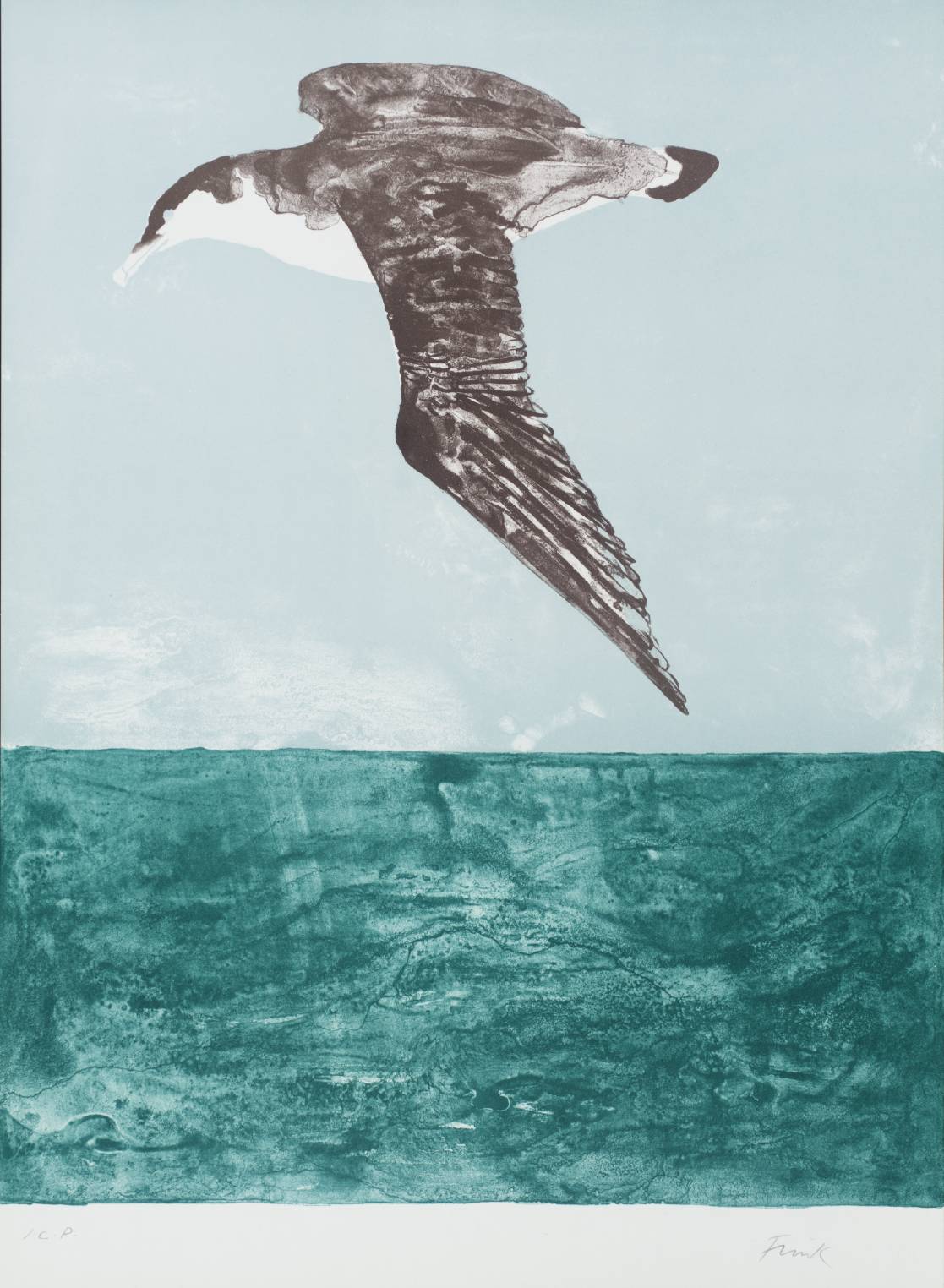

Dame Elisabeth Frink, Shearwater 1974

7/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

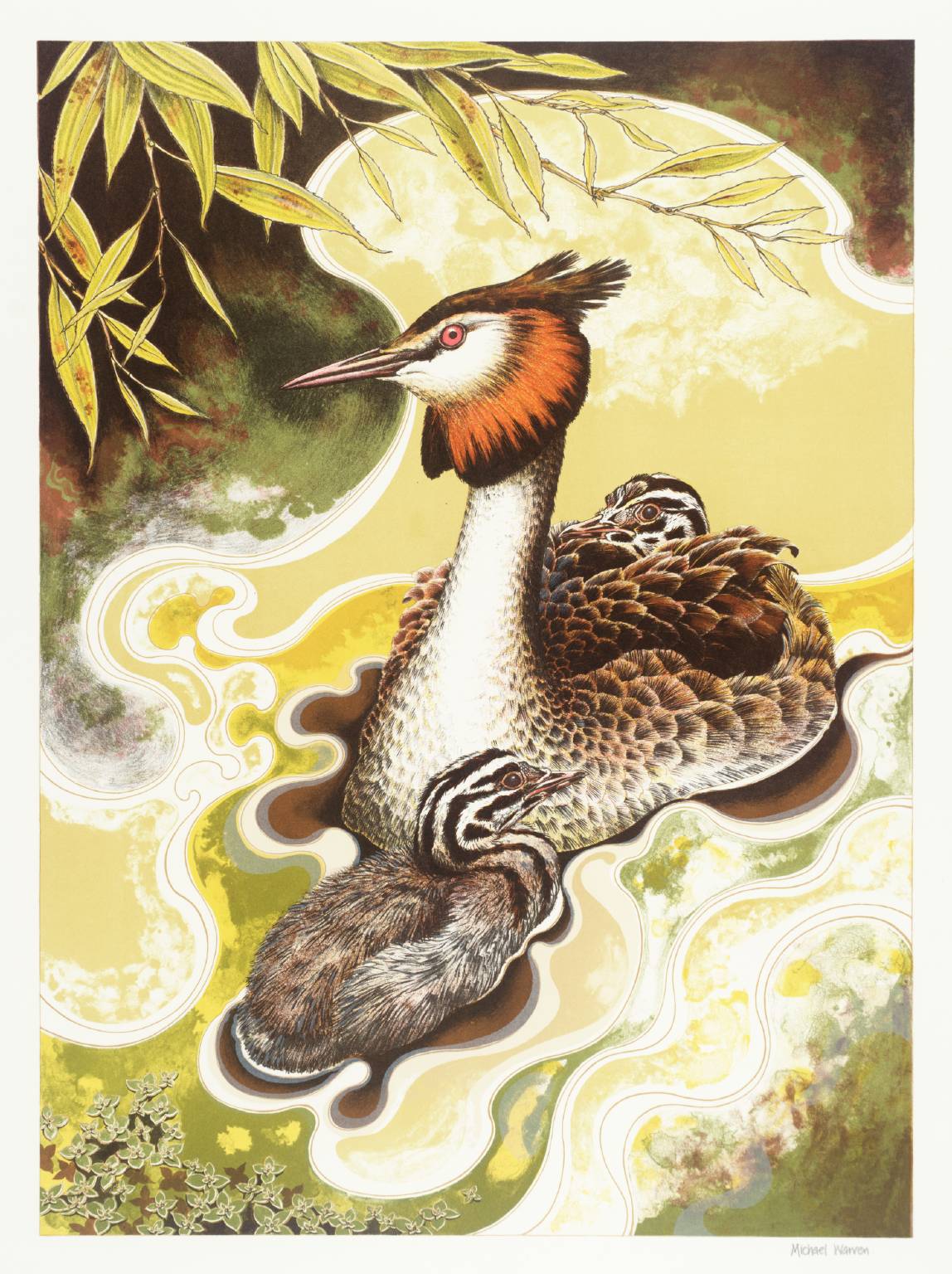

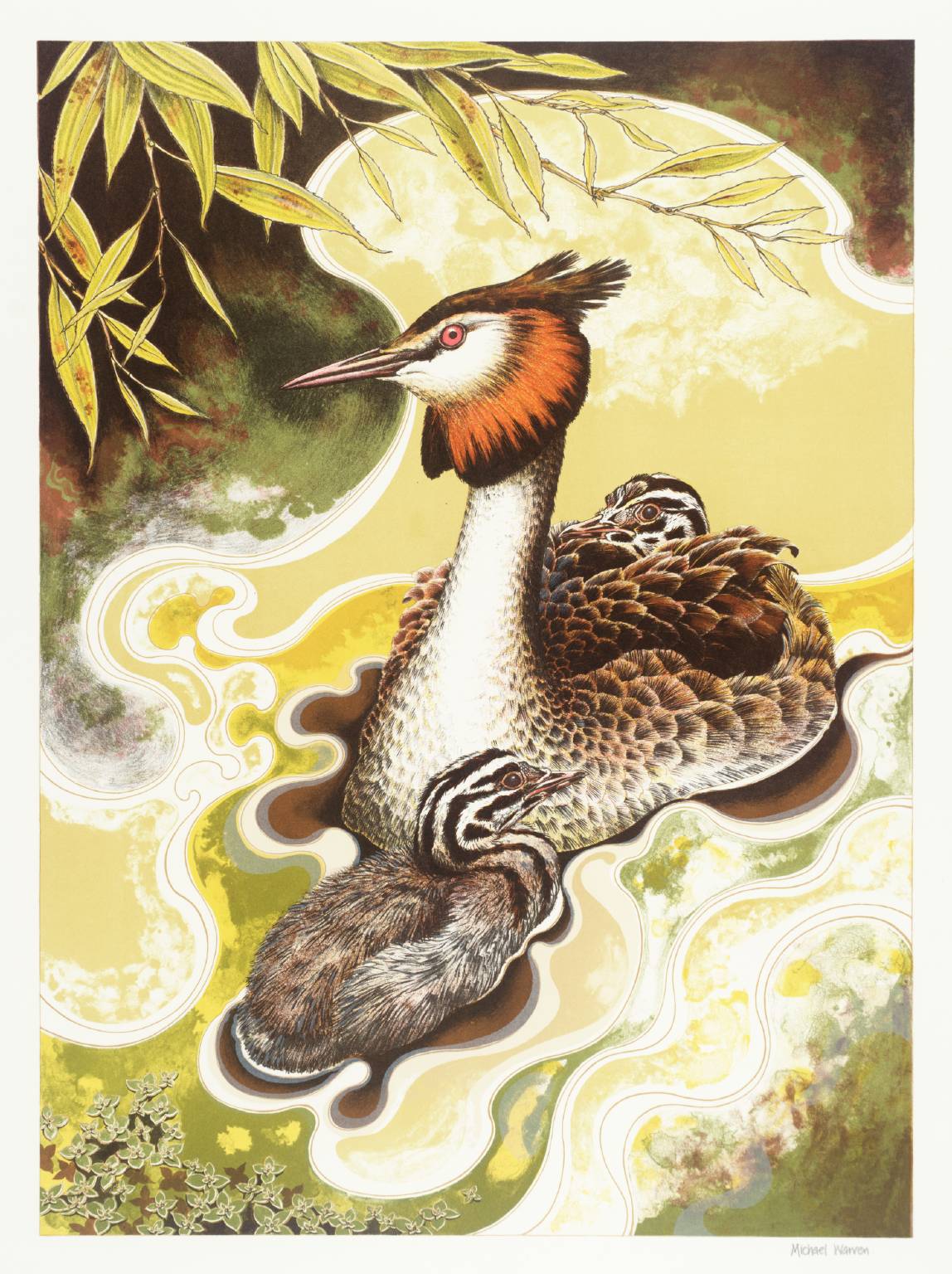

Michael Warren, Crested Grebe 1974–5

8/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Dame Elisabeth Frink, Eagle Owl 1972–3

9/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Don Cordery, Goshawk 1977

10/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Henry Moore OM, CH, Bird 1959, cast 1960

11/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

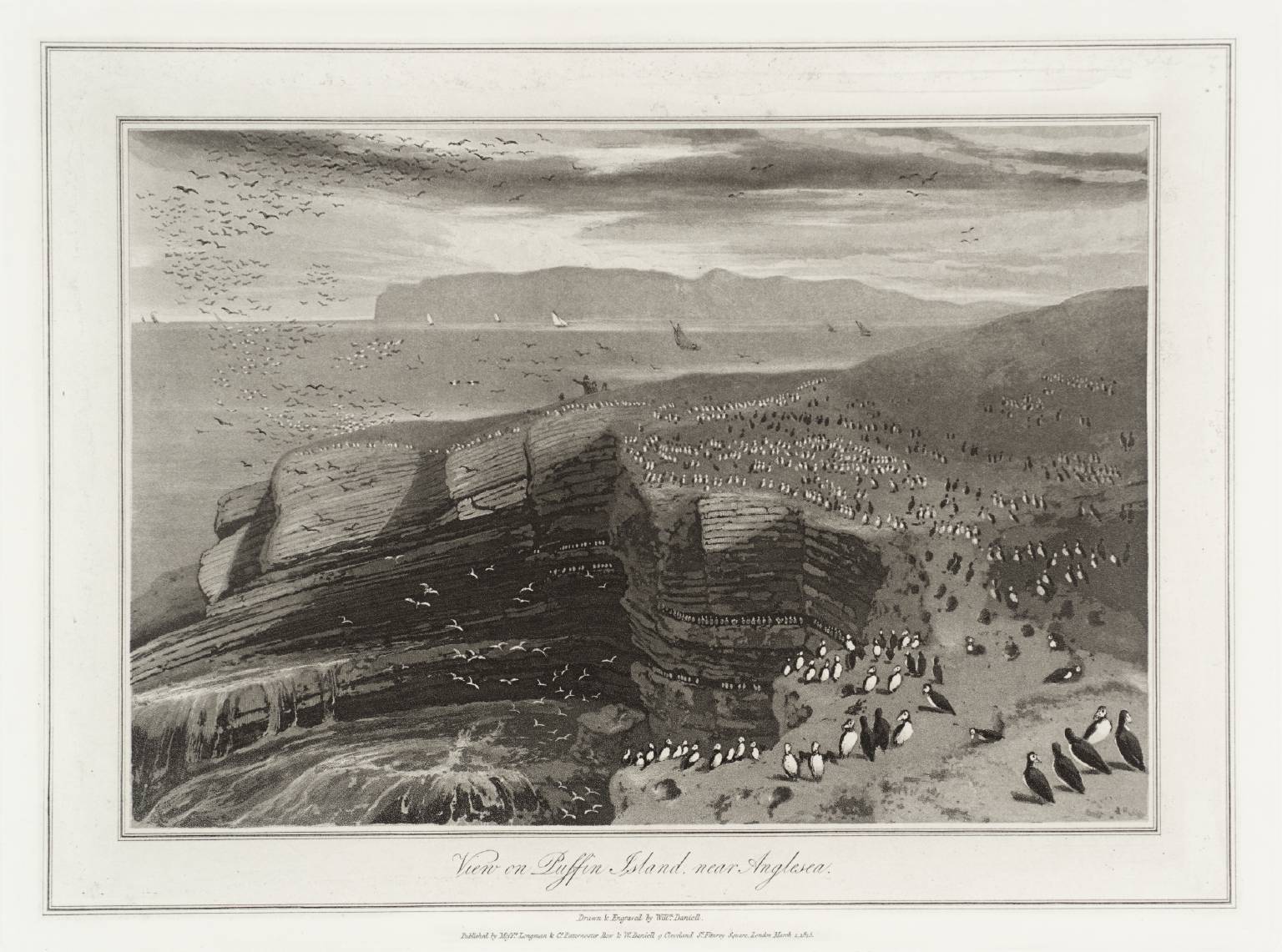

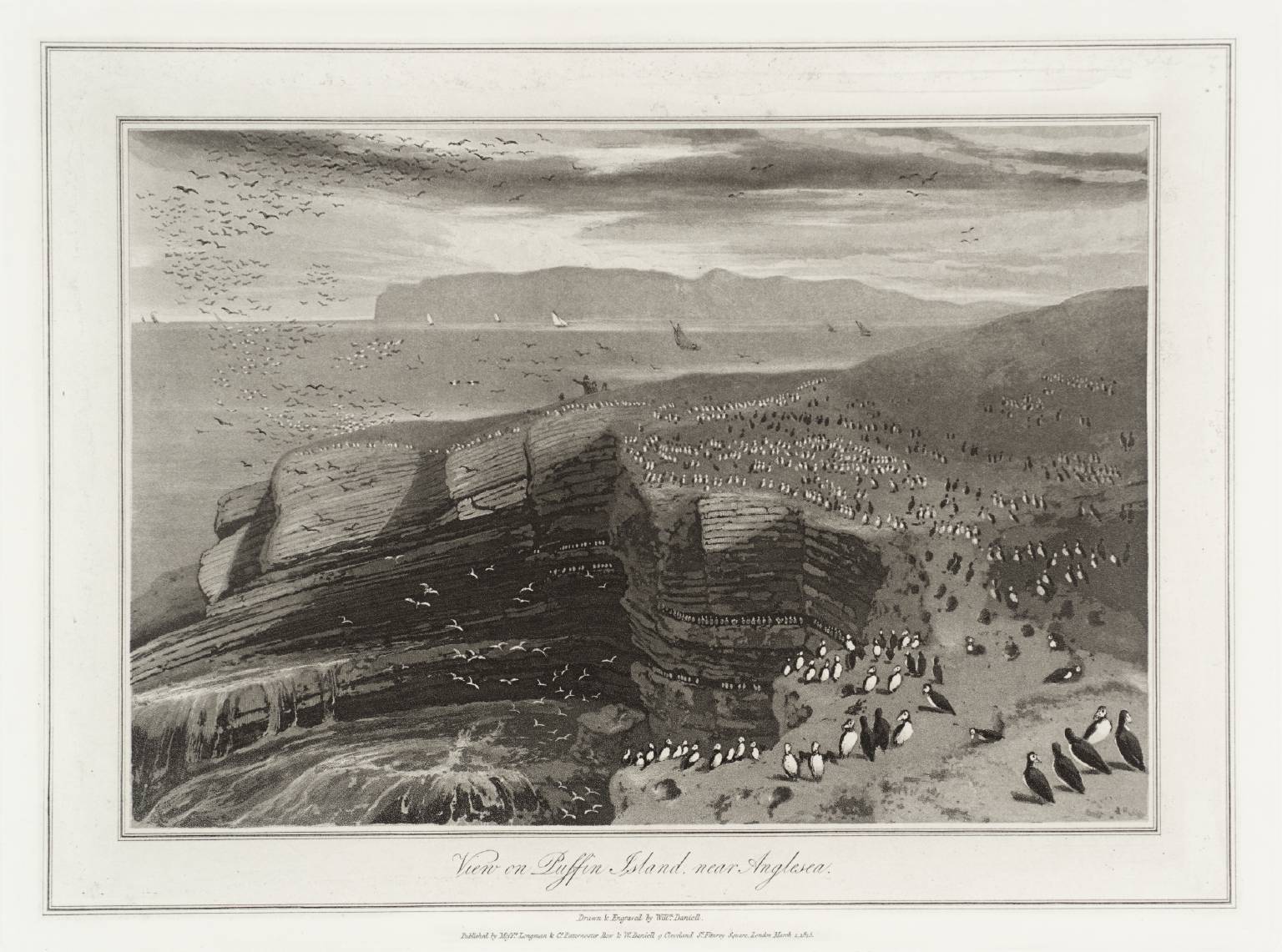

William Daniell, View on Puffin Island, near Anglesea Date not known

12/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Dame Elisabeth Frink, Bird 1952

This strong, alert bird is one of Elizabeth Frink’s earliest sculptures. She continued to explore the bird theme over the next two decades. ‘In their emphasis on beak, claws and wings… they were really vehicles for strong feelings of panic, tension, aggression and predatoriness,’ she said. But she resisted symbolic readings of these works. She cautioned: ‘They certainly were not surrogates for human beings or “states of being”.’

Gallery label, September 2023

13/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

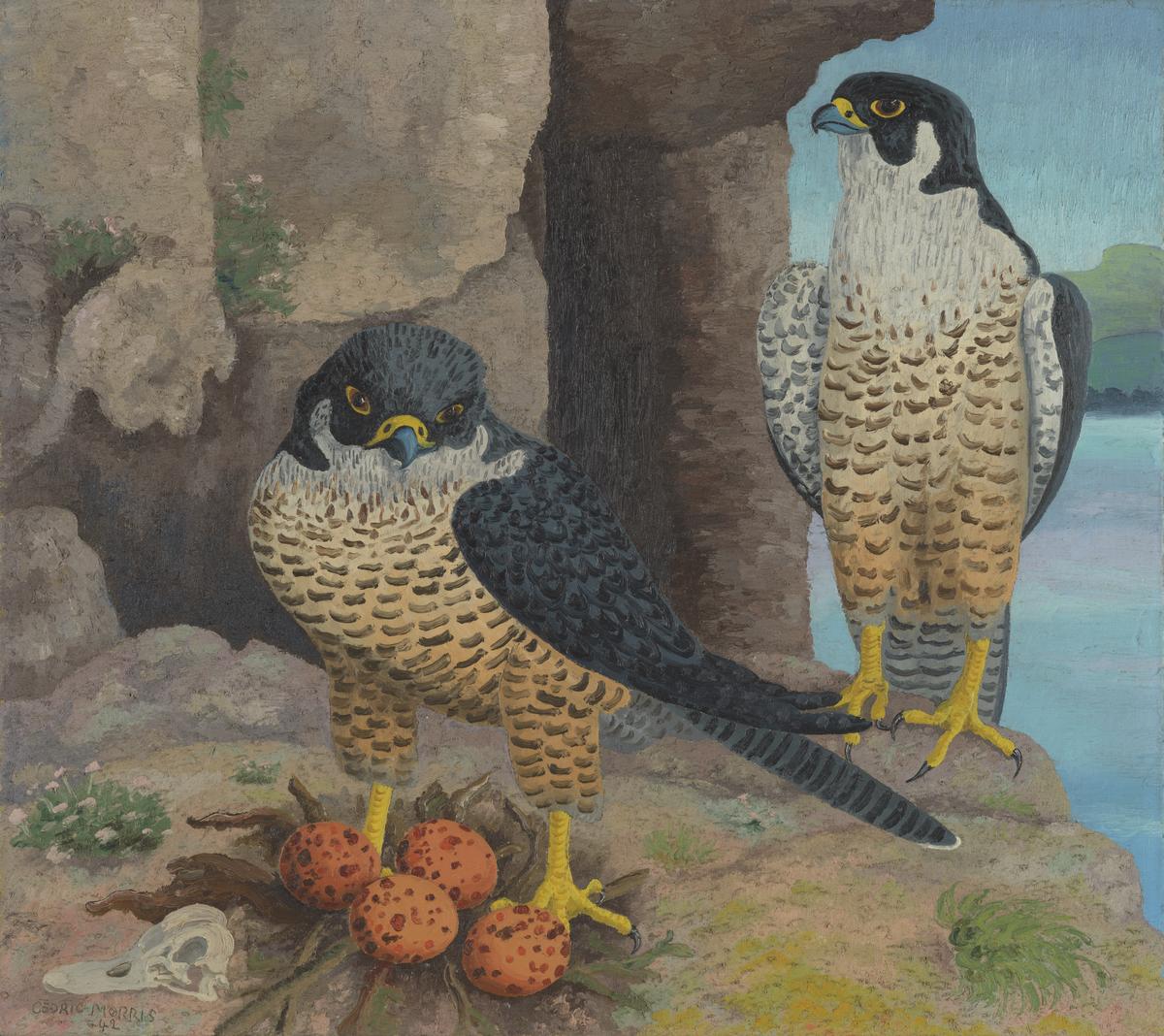

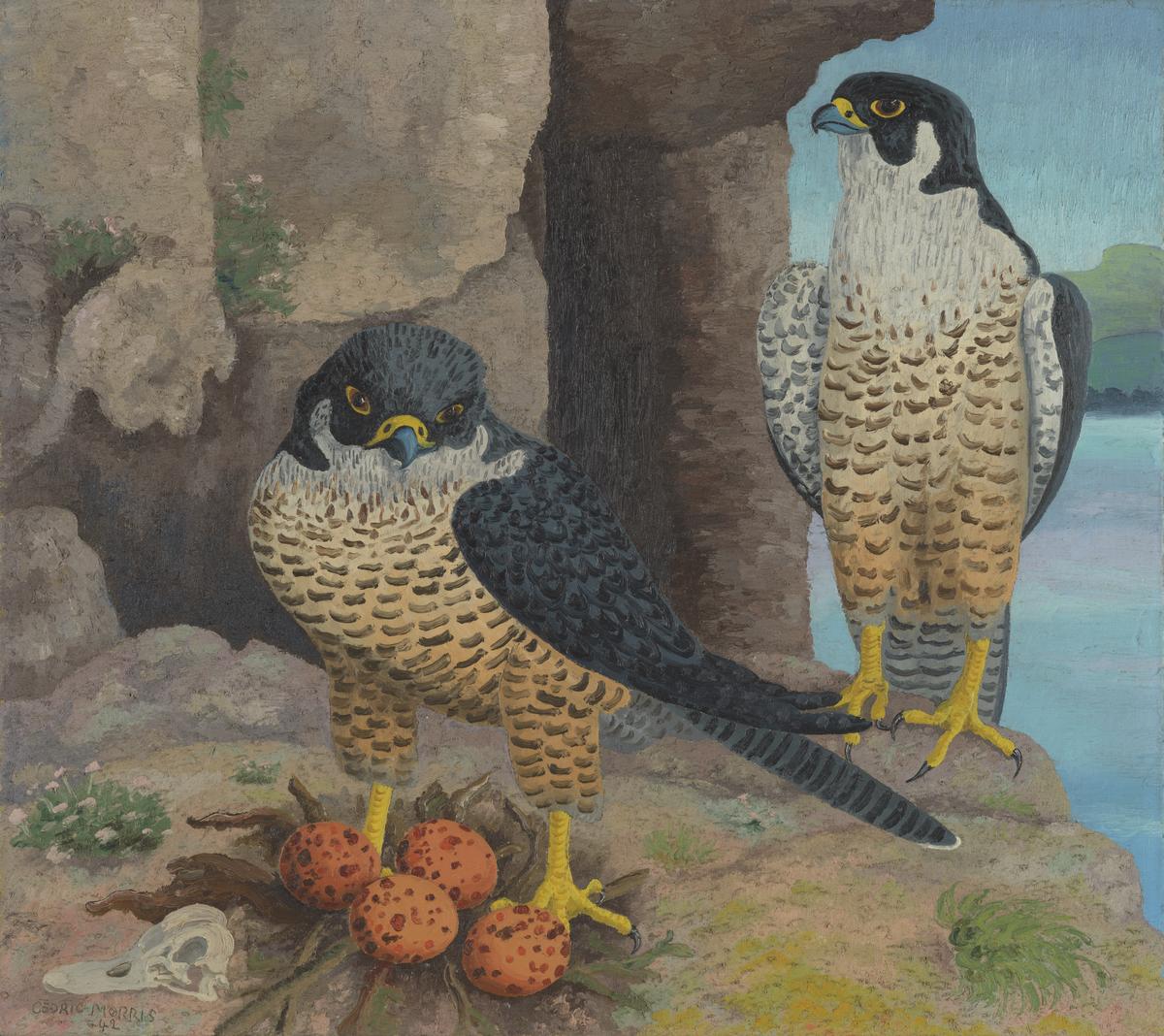

Sir Cedric Morris, Bt, Peregrine Falcons 1942

Not only did Cedric Morris paint birds, he bred them. His knowledge and understanding of these creatures may have contributed to his ability to re-create in paint, 'living, breathing, flying birds, not coloured reproductions of stuffed carcases', as one reviewer wrote of his exhibition at Arthur Tooth and Sons, London, in May 1928 (quoted in Morphet, p.32). In his analysis of Morris's paintings, Richard Morphet suggests that the 'unusual force of Cedric's paintings derives from the projection of the subject through a dynamic economy in combination with an acute sense of pictorial realism' (Morphet, p.82). In Peregrine Falcons, Morris does not attempt to record the exact physical detail of the birds or their surroundings. Instead he presents them in a slightly formalised and simplified manner, the intention of which is, in his own words, to 'provoke a lively sympathy with the mood of the birds which ornithological exactitude may tend to destroy' (quoted in Morphet, p.86). This lively sympathy is further enhanced by animating the paint's surface. As early as 1922 Morris's use of texture had been noted by at least one reviewer, who wrote, 'the light dances among the waves of paint, flickering brightly, so the whole work takes on the appearance of a mosaic, tapestry or precious enamel' (quoted in Morphet, p.29). In Peregrine Falcons the use of a spiky impasto for the birds and background enlivens them and gives them an actual physical presence. The composition of the painting and Morris's use of colour forcefully underscore the falcons's status as the subjects of the picture. There is a dramatic divide in the background between the rocks surrounding the bird on the left and the distant sky framing the one on the right. The move from shallow spatial depth on the left to extremely deep perspective on the right maintains the visual interest in both halves and pushes each bird forward. Likewise, the warm colours of their plumage and talons advance against the receding cool tones of the background. In the lower left, next to the four eggs, is a duck's skull. Its inclusion is a reminder of the predatory nature of these birds, and is typical of Morris's unsentimental understanding of the animal kingdom and its cycle of life. In an article titled 'A Left-to-Right Painter', published in the Evening Standard, 9 May 1928, the critic R H Wilenski revealed that Morris painted his pictures from the top left corner without any preparatory drawing on the canvas, proceeding inch by inch until he reached the bottom right corner. Although such a method might seem incompatible with Morris's statement in 1924 that 'all my pictures are painted from the original in the open air' (quoted in Morphet, p.91), there is no underdrawing visible in Peregrine Falcons. This suggests that either Morris changed his practice after 1924 or, as Morphet believes, that neither method was exclusively followed. It is not known where the picture was painted, though it is likely that it was at Benton End, near Hadleigh, Suffolk, to where he and Arthur Lett-Haines had moved The East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing in 1940. Further reading:Richard Morphet, Cedric Morris, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1984 Toby TrevesNovember 2000

14/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Francis Barlow, Cock, Hen and Sparrows 1680

15/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

after Francis Barlow, Ape; Cassowary; Feasant; Ostrich; Swallow; Peacock; Peahen Date not known

16/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

William Gow Ferguson, Still Life 1684

Ferguson was born in Scotland, but seems to have trained in Holland, where he lived and married. He also travelled in France and Italy. This is typical of his many arrangements of dead game, although he also painted fanciful architectural subjects for overmantels and overdoors. Subjects such as these were admired as craftsmanlike renderings of nature, recalling a good day out hunting. Ferguson is known to have supplied a pair of such pictures specifically for the Duchess of Lauderdale's Private Closet at Ham House in the 1670s, indicating that they were considered particularly suitable as decoration for small, informal spaces.

Gallery label, November 1996

17/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Richard Wilson, Lake Avernus and the Island of Capri c.1760

Lake Avernus, near Naples, lies in the volcanic region of the Phlegraean ('Burning') Fields. In classical mythology these were the site of the Underworld, or 'Hades'. The entrance to Hades was said to lie in a nearby grotto, inhabited by a prophetess known as the Cumaean Sibyl.

In Virgil's epic poem, The Aeneid, the Sibyl helps Aeneas, the Trojan prince, to enter Hades. There his father's ghost foretells his destiny as the founder of the Roman nation. Such associations made Lake Avernus a major attraction for landscape artists and travellers on the Grand Tour.

Gallery label, September 2004

18/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

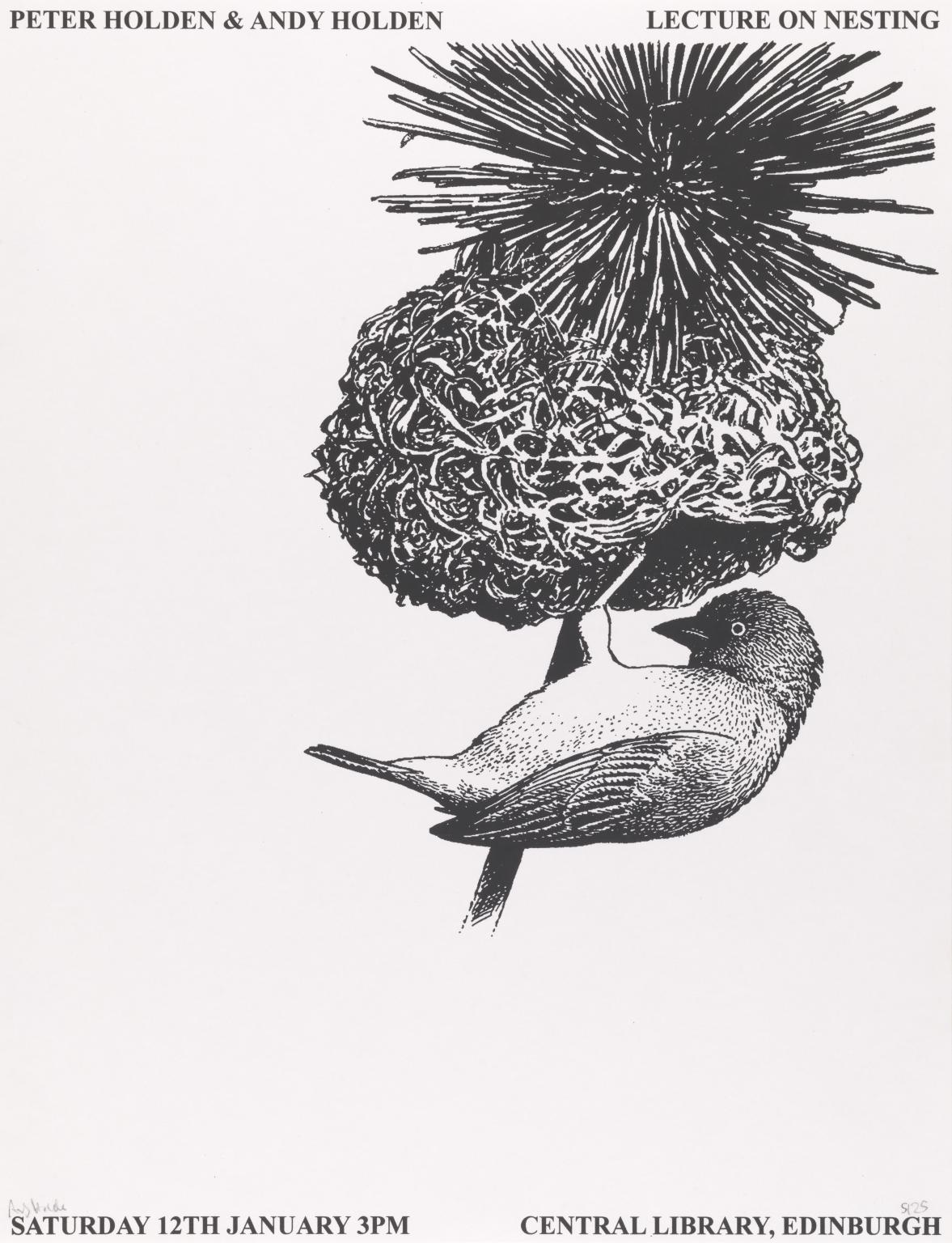

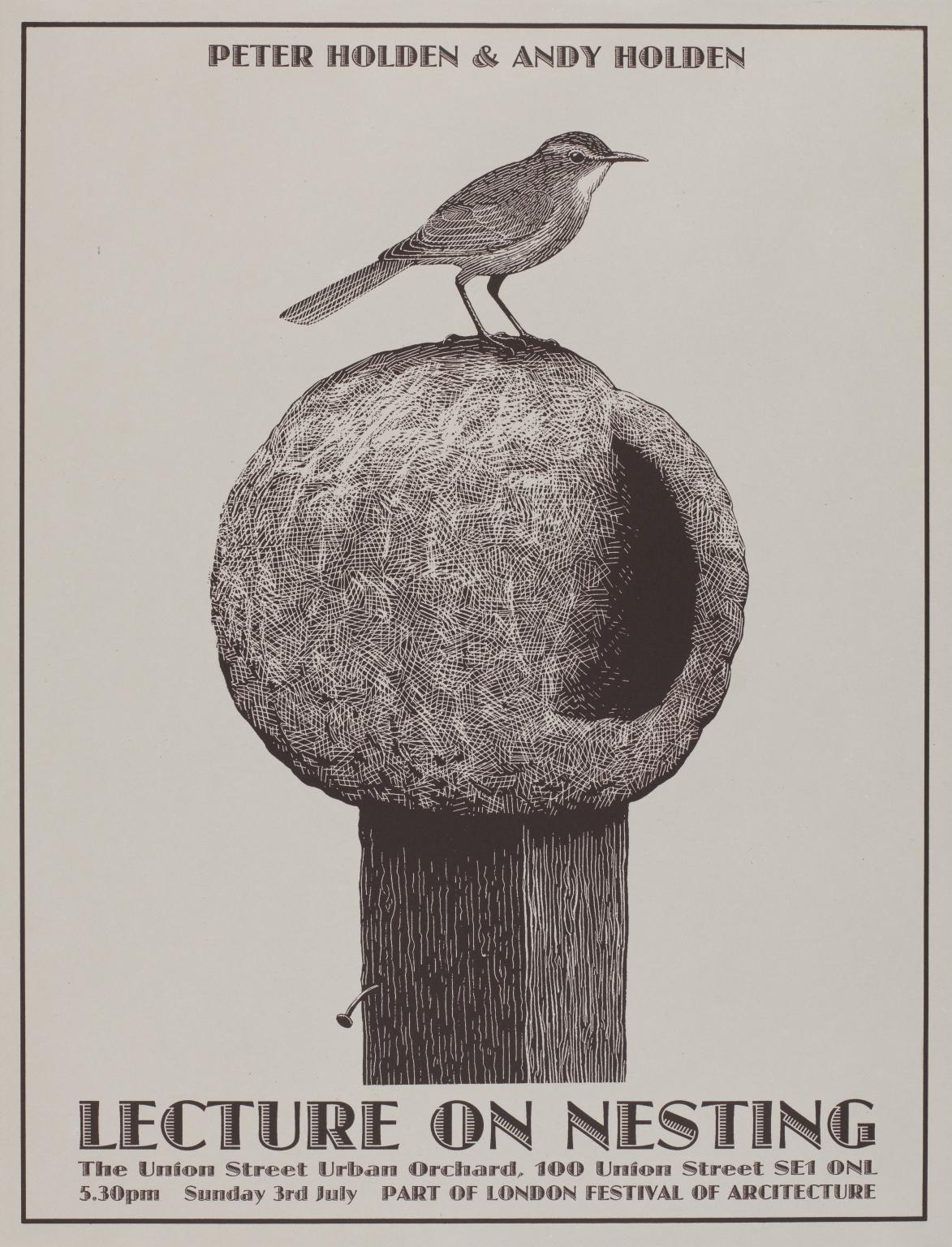

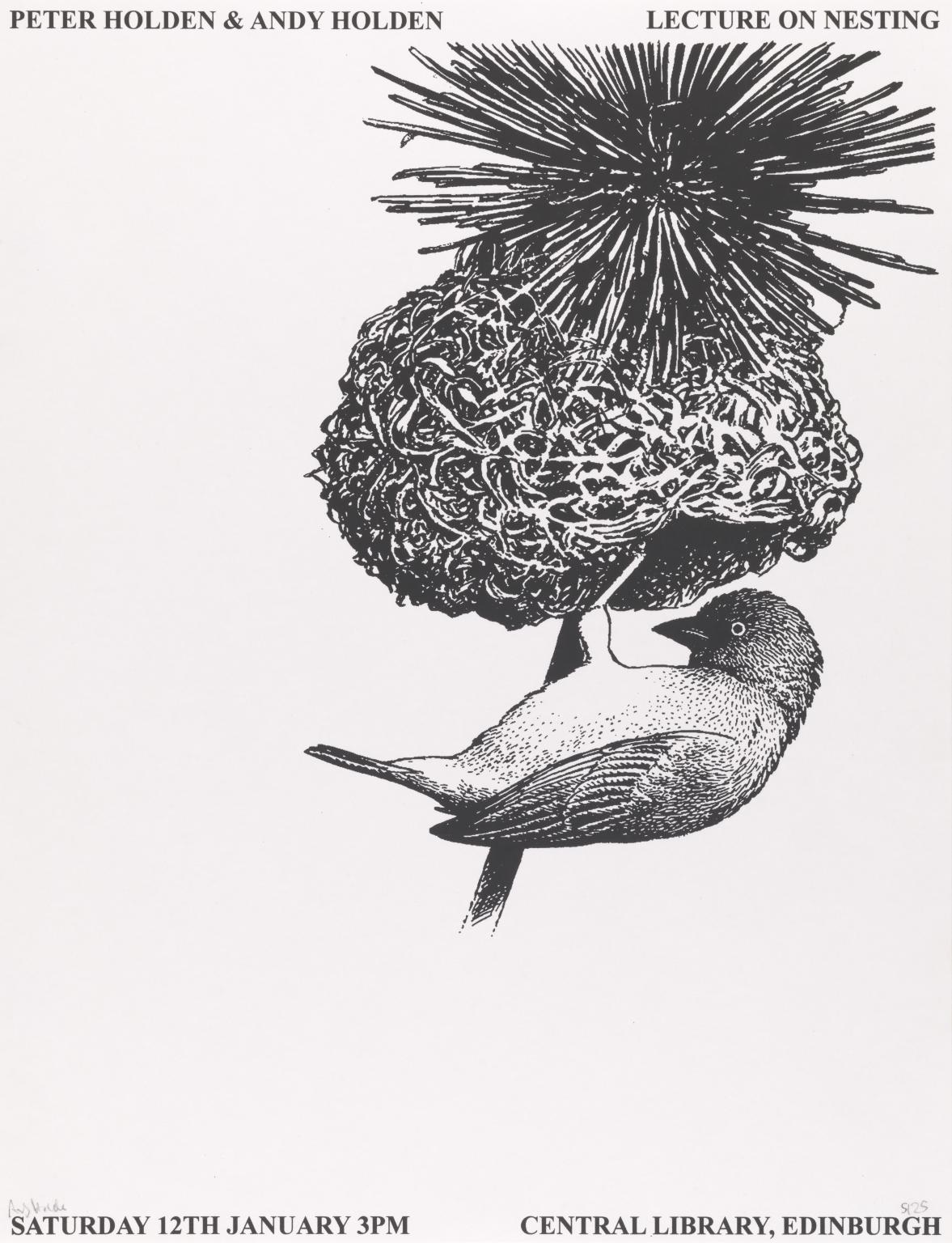

Andy Holden, Lecture on Nesting (Edinburgh Central Library/Collective Gallery) 2012

This screenprint features a black and white illustration of a weaver bird and its nest that was based on drawings found in the archives of Bristol Museum. The screenprint was produced with Collective Gallery, Edinburgh on the occasion of Andy Holden’s solo exhibition there in 2012, entitled Landscape and Folly. The poster commemorates the first filmed version of the artist’s talk, performed in collaboration with father, the ornithologist Peter Holden, which became the template for his video A Natural History of Nest Building 2017 (Tate T15535). The documentation for the talk was used to devise the script that developed into the film, setting up the premise of attempting to make a work that would appeal to two different audiences at once: from an ornithologist’s perspective and from a more creative artistic perspective. This talk was also performed at the Penzance Convention, Cornwall in 2012 and Performa 13, New York in 2013.

19/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Colin Self, Power and Beauty No. 6 1968

20/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Sir Cedric Morris, Bt, Landscape of Shame c.1960

Morris had painted birds quite often since the 1920s. Here he shows a variety of dead or dying birds in a desolate landscape. A rook and moorhen are in the foreground, and a male partridge dominates the centre of the composition. Morris made the work in response to the devastating effects of certain crop-sprays and pesticides on the bird population. Some of his friends have recalled his anger and frustration at the pitiful destruction of birdlife around his home at Benton End in Suffolk. The ill-effects of some pesticides were first noticed in the mid-1950s. By the end of the decade large numbers of birds were found dead in the fields.

Gallery label, September 2004

21/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

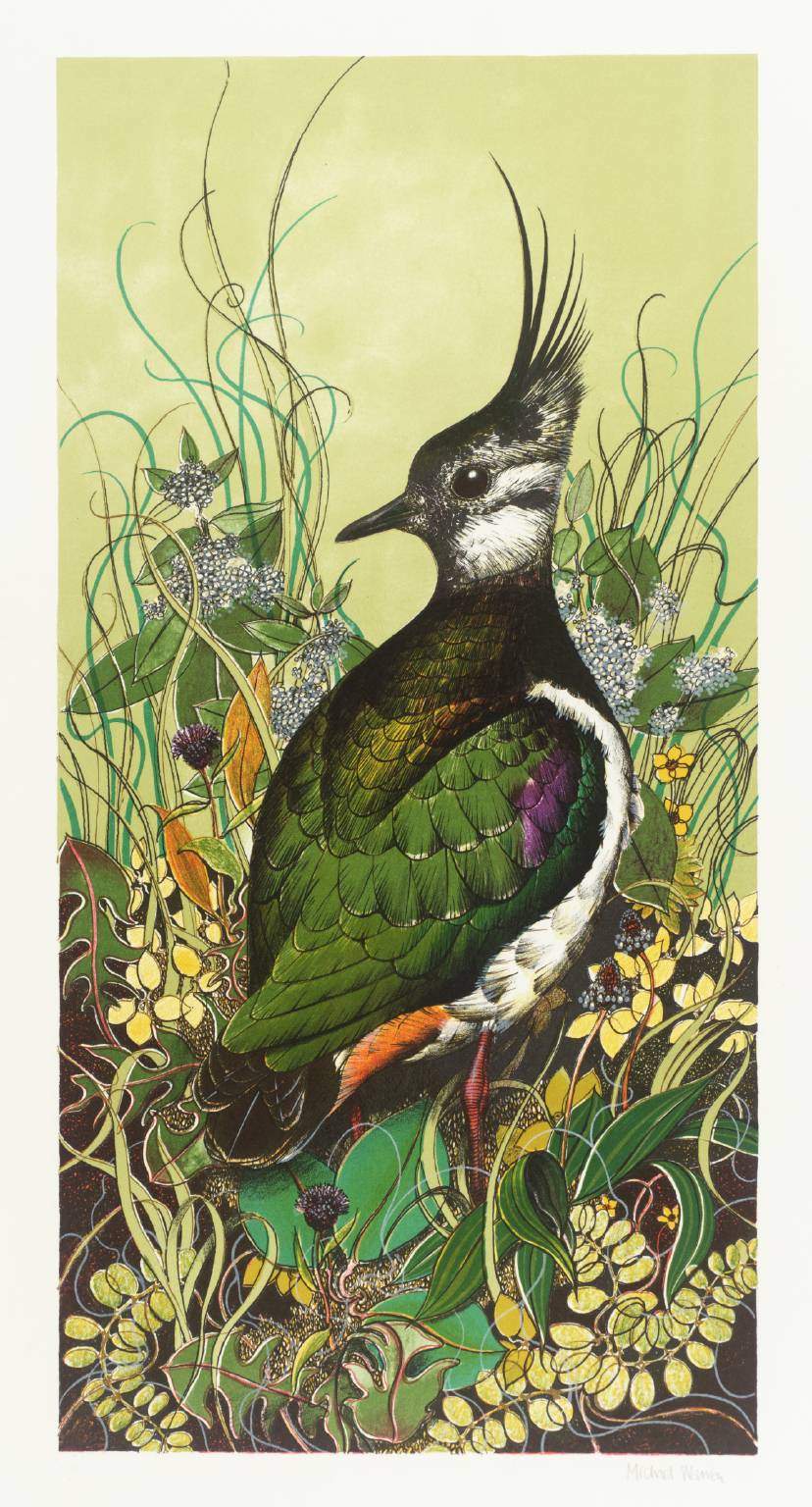

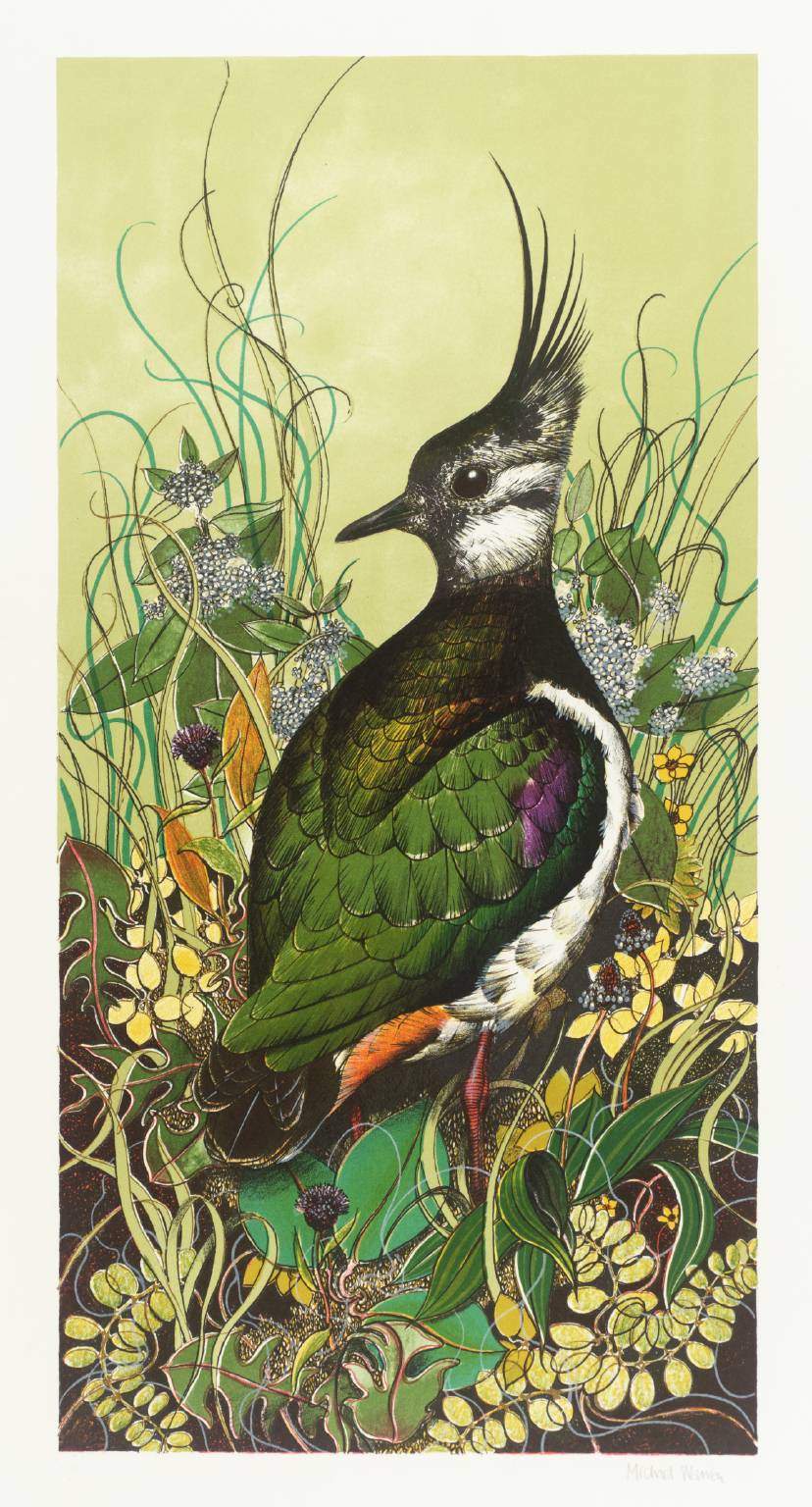

Michael Warren, Lapwing 1973

22/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

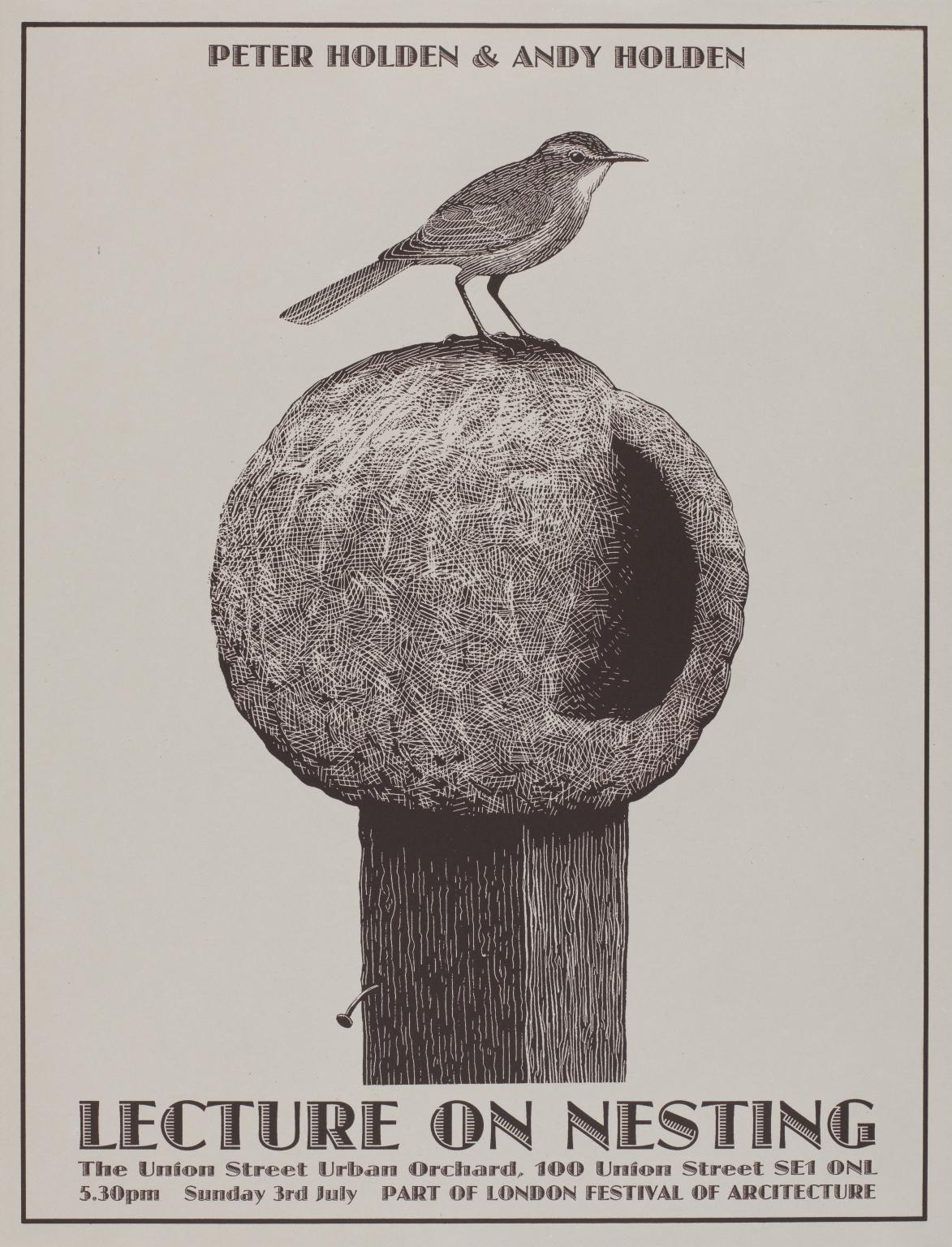

Andy Holden, Lecture on Nesting (London Festival of Architecture) 2010

This screenprint features a black and white illustration of an ovenbird sitting on a nest that the artist took from a small illustration found in a book borrowed by his father, the ornithologist Peter Holden, in 2010 and adapted via photoshop for screenprinting. Printed at St Barnabas Press, Cambridge, this was the poster for Holden’s first collaborative performance with his father Peter, which consisted of a forty-five-minute presentation on bird’s nests with slide illustrations. This short-lived presentation was mostly improvised. Peter Holden discussed birds’ nests from the point of view of an ornithologist while his artist son reflected on them as sculptural objects that had been ‘made’. Peter Holden’s tone was scientific while the artist offered a more poetic mode of interpretation. The performance drew on slides taken by Peter Holden during the course of his career, with some additional few photographs by the artist. This presentation was followed by a similar one, which was also improvised, at Wysing Arts Centre, Cambridge in 2010.

23/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Winifred Nicholson, Sandpipers, Alnmouth 1933

Throughout her life, most of Nicholson’s work depicted either flowers or landscape. This painting was made during a holiday on the Northumberland coast. It is typical in its reduction of the scene to a few simple areas of colour. Despite this abstraction it is still very evocative, not least because of her application of real sand to the paint denoting the beach. Nicholson’s paintings have an air of freshness and of the back-to-basics attitude upon which she based her lifestyle.

Gallery label, September 2016

24/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

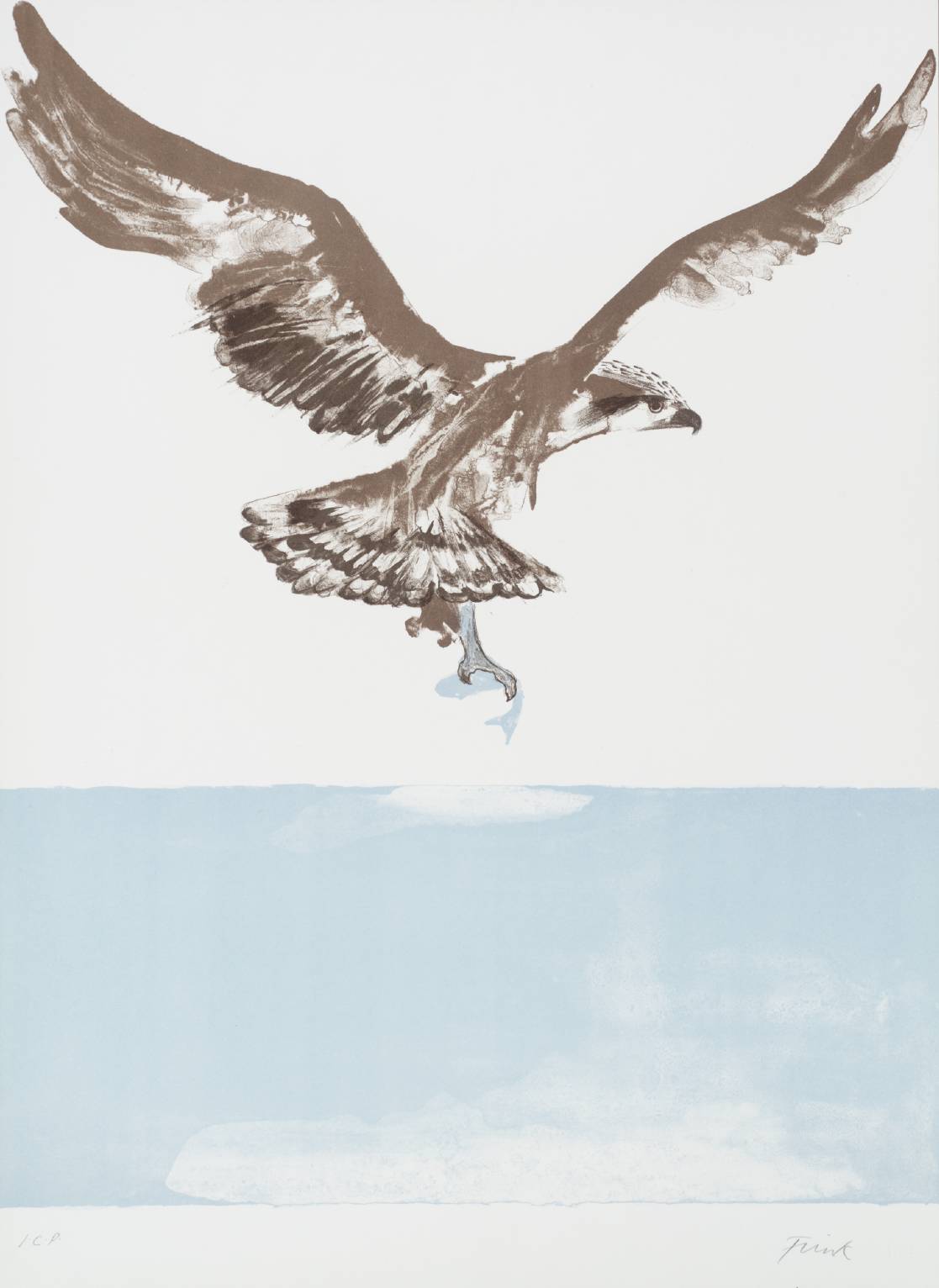

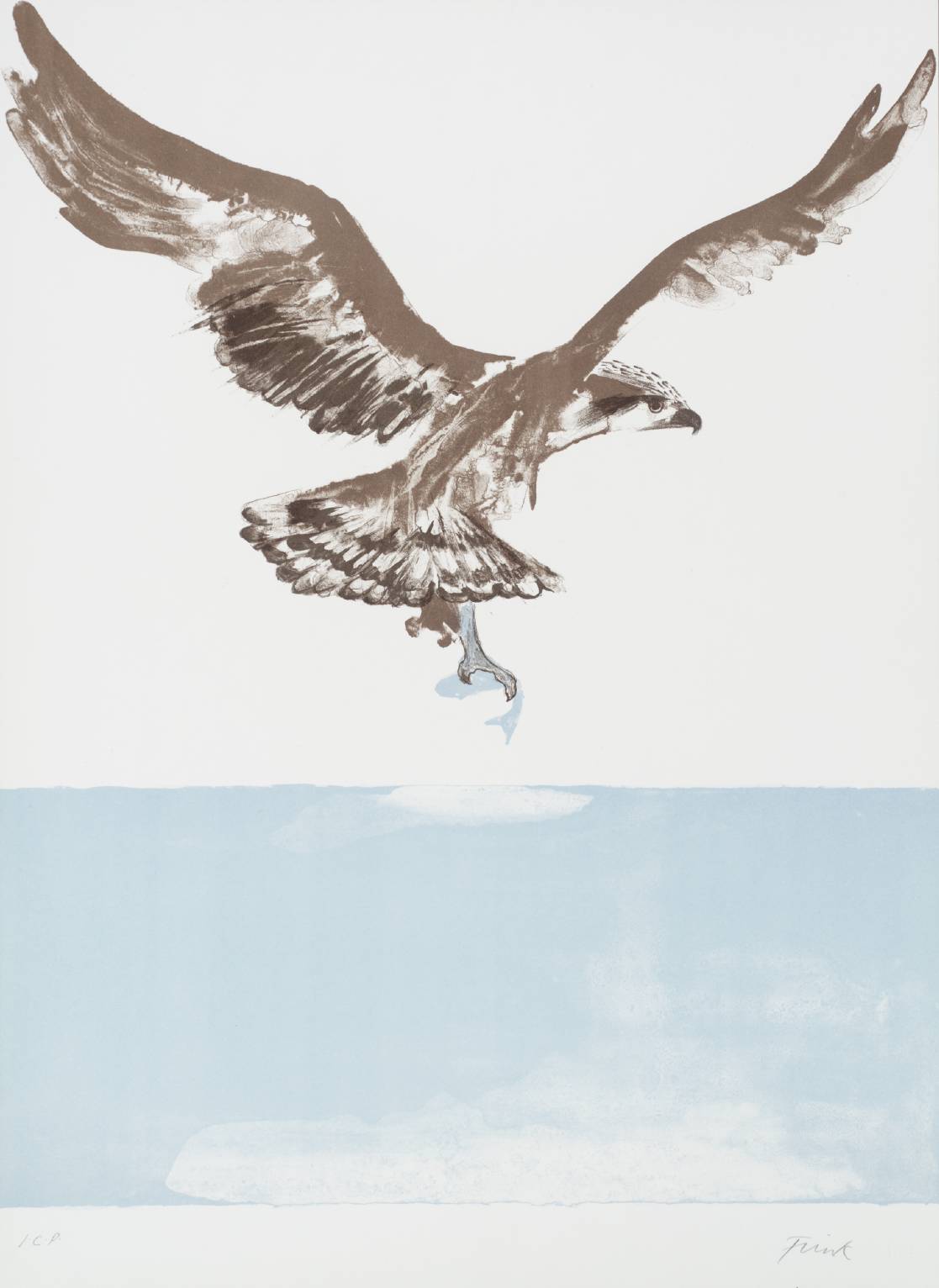

Dame Elisabeth Frink, Osprey 1974

25/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Pieter Casteels, A Fable from Aesop: The Vain Jackdaw 1723

26/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

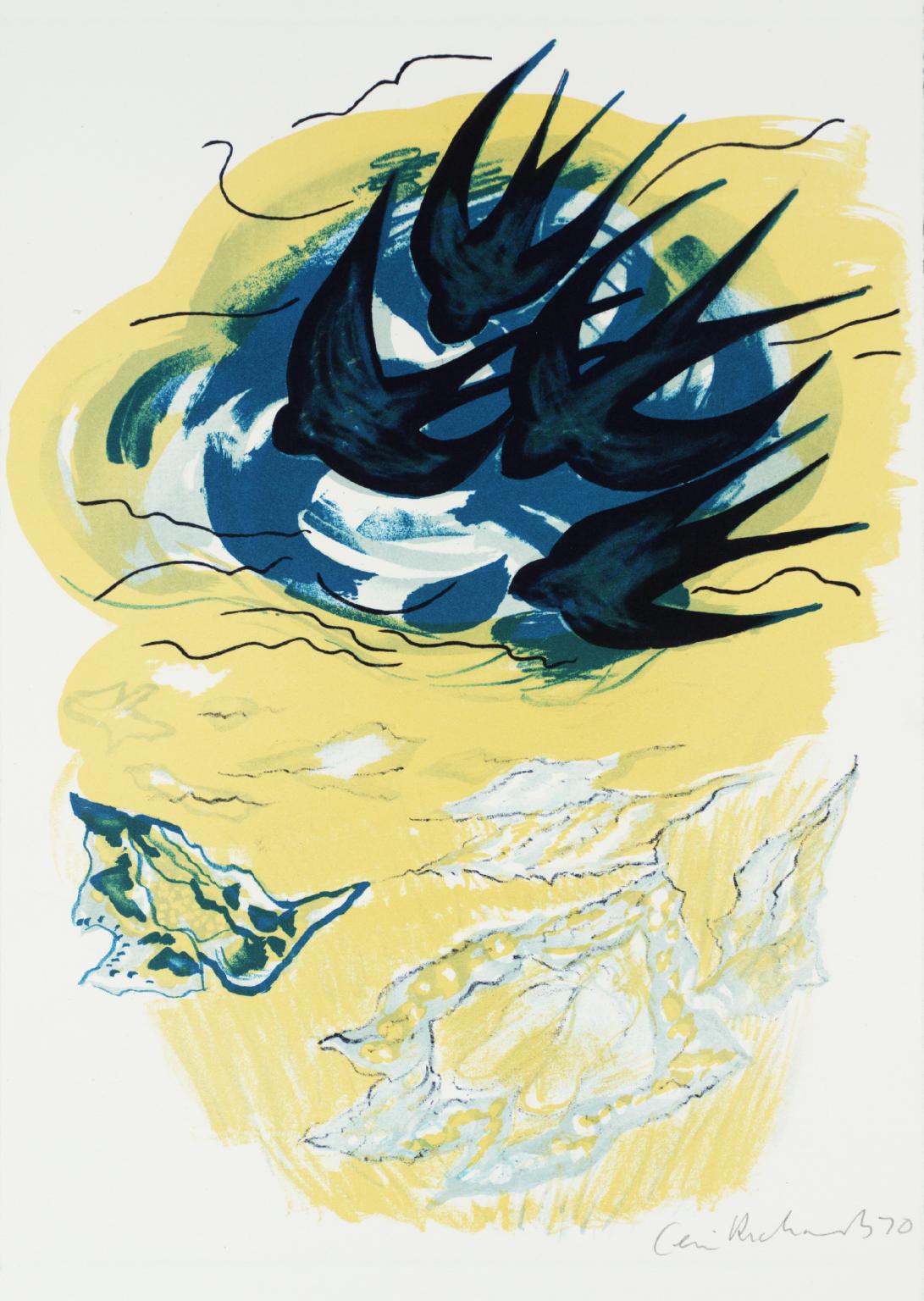

Ceri Richards, [title not known] 1970

27/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Colin Self, The Bird Table 1987

28/28

artworks in Stubbs and Wallinger

Art in this room

![P06486: [title not known]](https://media.tate.org.uk/art/images/work/P/P06/P06486_10.jpg)

You've viewed 6/28 artworks

You've viewed 28/28 artworks