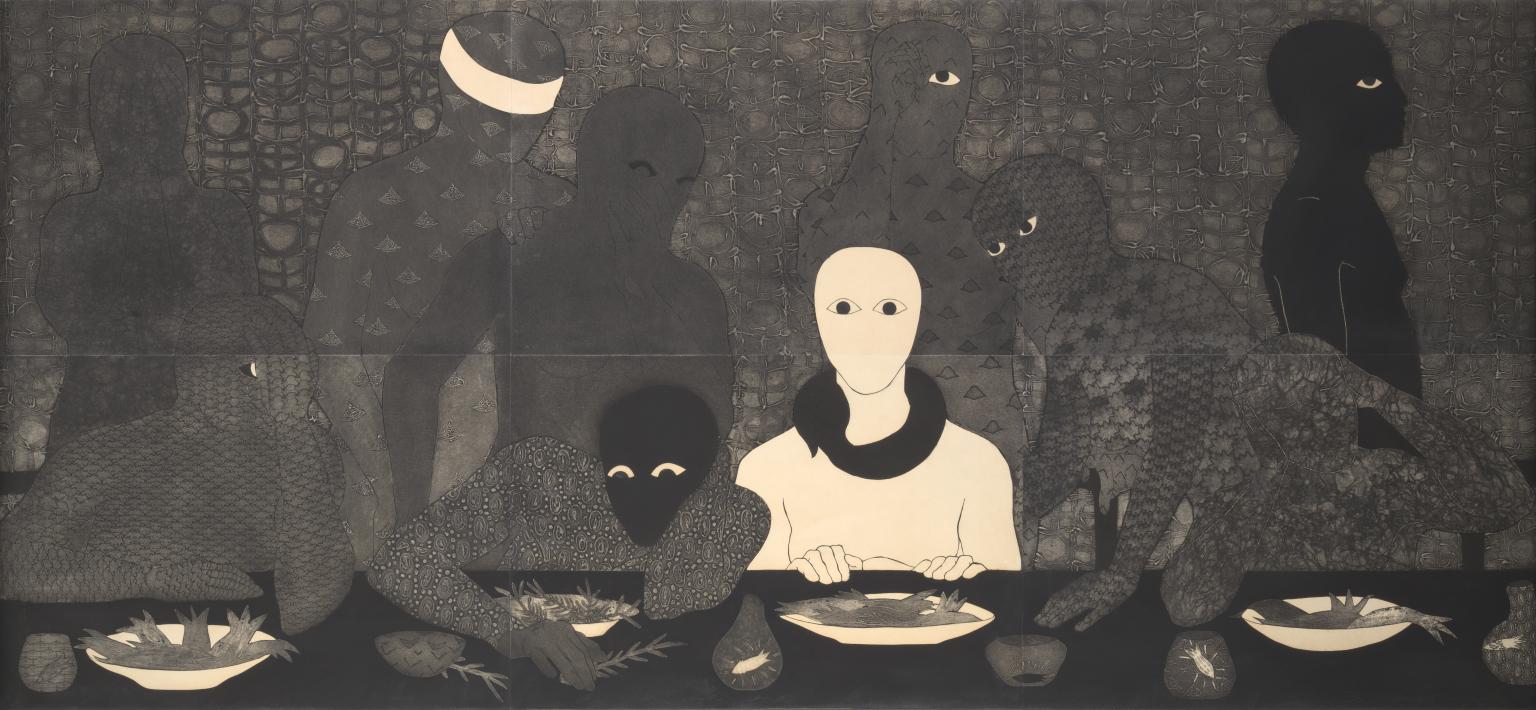

This display brings together two artists who work with textile traditions, drawing on them to create new sculptural forms

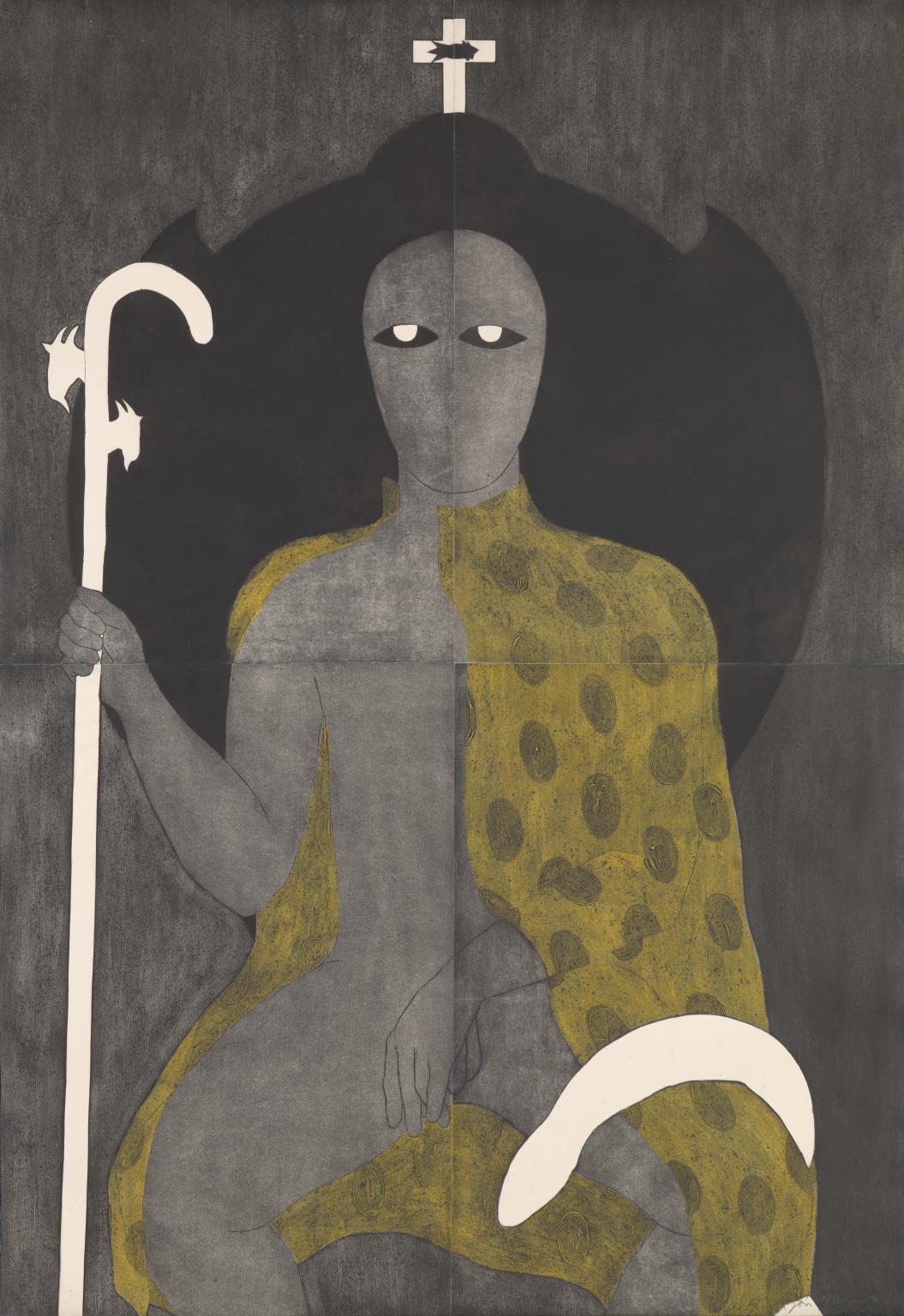

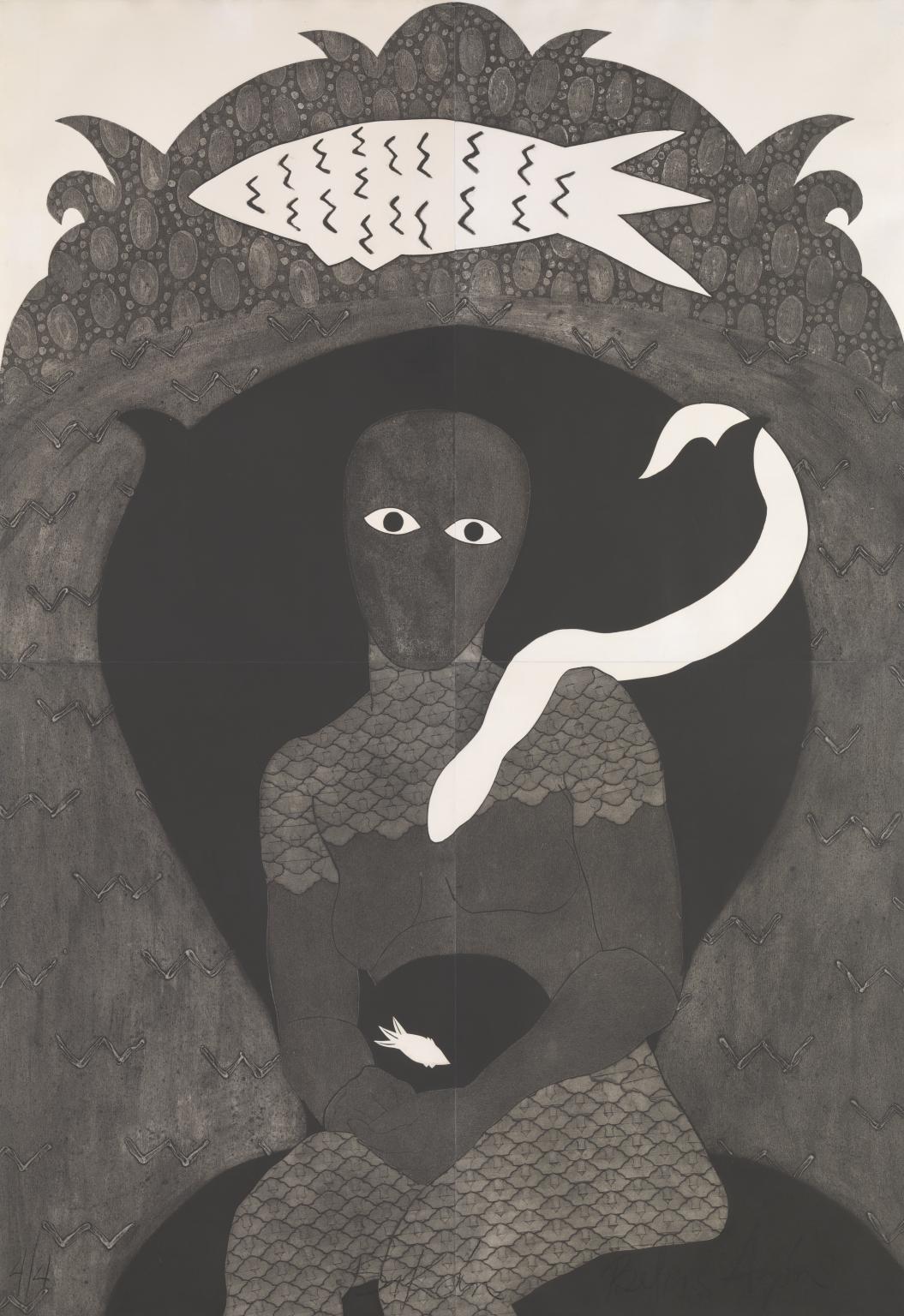

Jagoda Buić and Johanna Unzueta experiment with textile techniques from Croatia and Chile respectively. Both draw attention to how indigenous and local expertise, shared over generations, has informed their own process of making. Their works recognise craft practices as a constant part of the history of art.

Through her ambitious woven works, Buić became one of the leading international artists who demonstrated the possibilities of weaving as sculpture. She was associated with the New Tapestry movement of the 1960s, which used fibre as its central medium for art. Buić used traditional Croatian weaving techniques and sometimes worked with local weavers to create her complex geometric patterns. These referenced the landscape of the Dalmatian coast of Croatia and the region’s medieval architecture, such as castle turrets.

Unzueta’s drawings relate to both textile making and architecture. After art school, she worked as an apprentice to learn weaving, spinning and dyeing techniques from a Mapuche woman in southern Chile. Unzueta adapts some of these techniques to colour her drawings with natural dyes such as indigo. Unzueta designed each drawing to be held within a freestanding base to bring the work off the wall and into space.

Art in this room