Chapter 1

Our World/Their World/A World

Over the course of Art Now’s thirty-year history, many of the artists commissioned have focused on creating a shift in perspective. For some, these shifts have taken shape in the creation of new forms of intimacy; for others, sound and the object refract personal and domestic histories, and for artists working with film in particular, the medium has become a means to explore physical vistas as sites of political erasure and conflict. It is within these lineages that Onyeka Igwe’s exhibition, our generous mother, operates: a project that shifts perspective and foregrounds Britain's troubling colonial legacies.

our generous mother confronts us with a nation’s detachment from the construction of institutions in its former colonies through the stories and intimate spaces of the predominantly female students on the campus of the University of Ibadan (U.I.), Nigeria. U.I. was founded midway through the 21st century, and was the first elite university established in Nigeria, preceding the vocational tertiary education model that had previously existed. In Penkelemes, the film within the show, sites across the university are captured as vignettes of historical and contemporary political conflict. The tesseract-like geometric brise-soleil at the heart of our generous mother refracts these histories, removing their linearity, creating an active archive of constantly shifting perspectival moments.

This essay documents the research undertaken by Onyeka and I in preparation for the exhibition. Over several months in early 2025, we visited a combination of libraries, audiovisual archives, and architectural archives. These included the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), the Commonwealth Library and Archives, the Bodleian Library, and the Associated Press. In Nigeria, this included xxx Audiovisual Archive, the xxx library at xxx, the xxx archive and the xxx audiovisual archive in Lagos.1

The division of sources will not be revelatory to any researchers on West Africa; the number of libraries visited at home and abroad is equal. This speaks to how the process of researching the postcolonial state is part of the endeavour of retracing the fragmentation of resources along a path that typifies the processes of colonial interaction. That is to say, in research and practice, researching “the first Nigerian University” questions the very existence of a “Nigerian University.” Nigerianness is thrown into question; the institution’s hybridity is part of its form. Its influences fermented across a series of conflicts, firstly, a complex web of fractious politics that arose between the colonial state (Britain) and the emerging state (Western Nigeria, with its then fragmented regionalism). Between its representatives (colonial officers and officials), its literal architects (Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew) and its administrators (initially British academic professionals, eventually Nigerian Academics). Finally, between its workers (initially British and European tutors, followed by Nigerian tutors and administrators) and its students.

Any project that aims to create an archive of experiences, perspectives, and reflections on the colonial university, particularly that of U.I., as Onyeka’s does, grapples with this hybridity and must incorporate a plurality of perspectives that refract these stories across space and time. I will reconcile the stories, beliefs and tales that have been incorporated into this archive.

To understand the conditions under which a university can be a site of such contestation, there must be an insight into the context under which it was created.

Primarily, in Britain’s management of its colonies, every decision was guided by a careful monetary cost-benefit analysis towards further extraction. Put simply, British state concessions in terms of forms of governmental development programmes were motivated by optimising extraction.

The development of higher education in African colonies was no different. Embedded within the colonial system of indirect rule was the unassailable paradox that, to maintain control, the British needed a local educated populace to run the colonial system as administrators. Even though an educated populace presented an existential threat to the entire system, this remained true.2

In 1948, the University of Ibadan was founded alongside universities in Ghana (then the Gold Coast), Malaysia (then Malaya), Uganda and in the Caribbean (still known as the University of the West Indies). These universities were still under British dominion. Designated as branches of the University of London, or as the students at Ibadan would come to describe it, “the University of London situated at Ibadan for purposes of convenience.”3

Ade Ajayi Library, Jadeas Trust.

Chapter 2

Empire of Good Practice

In the colonies, direct forms of taxation paid for educational development, despite the grotesque heaps of amassed surplus value the British Empire extracted.4 To describe educational systems in these countries, I will paraphrase the Marxist theorist Walter Rodney: the educational pyramid had a narrow base and a shallow slope; that is to say, it served very few Nigerians, and of those, only a limited number could make it through the pyramid.

This design maintained an elite group that was limited in number and scope. In its first year, only 210 students arrived at the university to study. As described by the historian and author Tim Livsey, this period represented a “second wave of colonialism.” A moment where, in the transition from the post-war period and the attempts to prevent the collapse of the empire, there was a mobilisation of colonial governance through state-building.

At newly founded universities, this meant the wholesale importation of a British academic establishment. A top-down university policy from Britain dictated the mass arrival of administrators and educators. Intertwined with private and state enterprise, colonial officials and members of partially state enterprises, such as the Cocoa Board (responsible for cocoa exportation), would discreetly serve on university councils. The Lagos government would vet appointments with criteria set by the UK government.

In architecture, this meant the importation of British Architects to build and design the new state. Principal architects in designing this expansion were the couple Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew. From 1946 to 1956, they were responsible for developing new sites and expanding existing ones throughout West Africa. The Colonial Development Fund, a government fund that operated within colonies, provided grants to support the development of infrastructure, which significantly aided their early work. At times, private industry supported their work; for example, Lever Brothers/United Africa Company (now Unilever) financed some building projects. Over the course of ten years, Fry and Drew would complete seventeen educational commissions and twelve commercial ones across what was then known as the Gold Coast.

In Ibadan, their designs were met with rancour by administrators who viewed them as too expensive; other critics took against what they saw as a patronising form of modernism. The famed tropical modernist patterns for which they are well known were simplifications of patterns from Ghanaian textiles—taken from mats, baskets, and cloths and then redeployed in concrete across West Africa. Ashanti stools inspire the balconies at U.I..

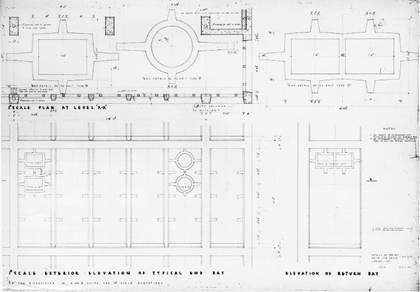

Architectural Drawings RIBA

Describing the intent of their work, Fry expressed that Ibadan was “deliberately geometric and orderly because such a statement is required against the extreme disorder of the luxuriant forest.”

Kenneth Dike Library, Ibadan

Separation was the aim of the second wave of colonialism. The modernising mission would reshape the colonial state from its predecessor, introducing fresh institutions with British standards, and propagating a culture that served to create a modern Nigeria.

It did not work.

The modernism of Ibadan was always a broken imposition on the existing climate. As J.F. Ade Ajayi, historian and former Dean of Arts at U.I., described it, there were “two distinct Ibadans in one,” the modern space of the university was understood in contradistinction to most of the urban space of Ibadan.”5

Chapter 3

Visions of Ibadan

“I look around this room... and I see a pattern: I don’t see you. I see you as a form as it relates to your environment. I see that there is a plane, you see, I’m very conscious of these planes, patterns.” - Jacob Lawrence.6

The first African Nobel prize laureate, Wole Soyinka, studied at U.I. during its foundational years before the opening of the Fry and Drew buildings. He nostalgically described the magic hybridity of the original campus. Remarking of Eleiyele that it had “a magnetic field for the bizarre… a sense of integration into physical surroundings and humanity, all of which appeared to vanish when the campus moved to its new home.”7 For many, the modernist campus was a structure of alterity, built to contain openness to the real Ibadan.

Yet when the modern buildings opened in November 1952, much of the population gained a new sense of pride. An emerging notion that the university had come to embody a space for a new elite.8 This notion of prestige reappeared consistently across interviews spanning multiple generations. In discussions, it was an impression enforced by parents who said it was “a good school,” popularly known, according to sixth-year student Toyinbo Adedeji, as “the first and best in Nigeria”, in academia, that renown held, referred to its 60s incarnation as “a Harvard for African Literature.”

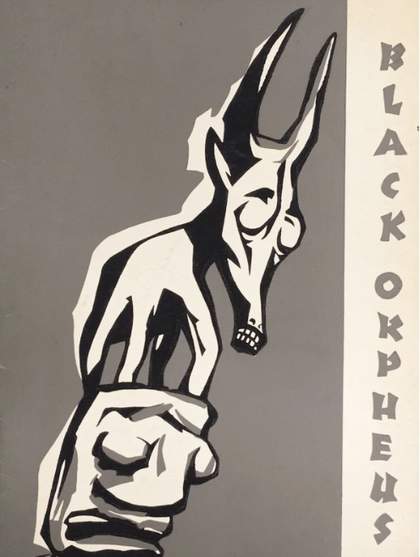

Linked directly to the metropole and with widespread regional cultural connections, the spatial reach of Ibadan was undoubtedly powerful. It was an intellectual home to writers such as Achebe, Clark, Okigbo, Tutuola, and Soyinka, as well as artists like Nwoko, Kuti and Akolo. The collective cultural workers disseminated the Mbari club model, creating new artistic avenues across Africa and beyond. Through the publication of Black Orpheus magazine, influence spread not just through institutions but also through its outputs. For all the influence it shared, it also attracted outsiders, foreigners and students from across Africa. It was a place of reconnection for the American artist Jacob Lawrence, and it was a key arena for the exhibition of the early work of Sudanese artist Ibrahim el-Salahi. Ibadan was a portal, a place of magnification, that amplified work and status.

Black Orpheus Cover

The status-raising notion of Ibadan applied equally to its degrees. As an effective tool of social mobility, the university degree was, as Achebe described, a “philosopher’s stone… that raised man from the masses to the elite.”9 A refrain that again persists until this day, as Toyinbo also stated of U.I. that it was “a school for the common man.” Yet, it was not just a school for increasing access but to raise an elite, as a longtime U-ite and professor emeritus, Daniel Azevbaye, reflected that he was part of a “privileged group of students.” Students who were served lunch by uniformed stewards and who were sought after by various companies that came to the university on recruitment expeditions. This contrast of elite yet accessible speaks to the breadth of experience, as Ibadan embodies multiplicities. Through all of these interactions, we were, as Lawrence describes, seeing patterns, broad strokes of an environment, tinged at times with prominent endorsements and silent admonishments.

We even encountered rosified, romantic visions of Ibadan memories that carry fondness for life on and off the campus. As we sat in the warm, dark wooden office of the Jadeas Trust Library, Mrs Ajayi spoke softly of the last house on the road leading to the Awba Dam, of the good life she shared with her husband, the aforementioned former Dean of Arts, where they had lived on campus from 1958 to 1991. Oscillating between the past and present tense, she spoke of a life shared, embedded within a commitment to documenting the history, politics and establishment of Ibadan. Realised in the library she now runs and makes freely accessible to the public, maintaining her husband's legacy, supporting undergraduates and researchers.

Awba Dam, University of Ibadan.

Within the same period in the 1960s, Mrs Wamuo was studying at University College Hospital, the hospital and medical school that runs parallel to U.I. She reminisced about preparing for nights out on campus, the ritual of buying material from the Lebanese shop in town, and taking her new fabric to the tailor in Mokola Market to have a dress made for the evenings. She recalled the Havana Music Festival, organised by the Sigma Club fraternity (est. 1950), with Victor Olaiya and his all-star band performing in Yoruba. It was during her university years that she met her husband, with whom she shared most of her life.

This blend of memories speaks to Soyinka’s experience of space, a jumbled experience that cuts across the regimented institutional geometries and percolates amongst the busy city. These visions of Ibadan seep across time; they are at times incomplete, dictated by fleeting feelings and faltering memories. To reconstruct this archive of place, we must reassemble and augment. In many ways, fleshing out the stories helps us better understand them as closely as possible, drawing on a set of archival experiences. There is a limited visual record, with too few recorded films that reflect an understanding of the environment beyond the colonial gaze.

Chapter 4

Overseas Film and Television Centre (OFTVC)

A complication of this history is the absence of a filmographic record. In Nigeria, film arrived as it had in many former colonies, as a medium that made people subjects of the British state agenda. Didactic in tone, the colonial project and its film units categorised people, subtracted their voices and characterised them as sets of conditions to be fixed: people to be educated, modernised and civilised.

The pre-independence films foregrounded the officialdom of colonial governors, and within this footage, the interconnections of the colonial project became clear. In OFT00862 (Associated Press catalogue number) used within the film, the colonial governor of Mauritius, Hillary Blood, is trailed to the foundation day of U.I. by a film unit tied to the colonial government in Mauritius. Here, the images are of the duties of colonial officers; it is from these stills that Onyeka excavates the early history of the university.

These films were likely shot by filmmakers from Mauritius and Nigeria. As was customary of the units, the home nation and the touring nation collaborated. The unit would have most likely had a British director who would head the unit; the labour of making the film would have fallen to the locally trained unit members. The film would have been shipped to Britain for development at the Central Office of Information and paid for out of the colonies’ respective budgets, which, like universities, were raised from direct taxation. The colonies sent the film material to Britain for development and production, where the masters were stored.

The colonial government would have likely requested that the film prints be distributed for exhibition in the colonies, with projection to a limited audience in Mauritius and Nigeria.

This model would continue with minor tweaks; the government department, the Central Office of Information, would become a private company, the Overseas Film and Television Company (OFTVC). The filmmakers trained at the units would come to fully take over the filmmaking apparatus, creating national film units that remained dependent on sending material to Britain to be filmed and developed. As ever, this was paid for by the nation; in the pre- and post-independence eras, Nigeria paid for production.

In Nigeria, there were multiple film units, including the Federal Film Unit, the Western Region Film Unit, the Northern Region Film Unit, and the Cinema Corporation of Nigeria, based in Enugu. These units, which reflected regional identities and the jockeying for power and influence, represented the distribution of political power before independence.

Television mirrored this process; the colonial administration established the state broadcaster, Nigeria Broadcasting Corporation (NBC) in 1951, initially supported by the BBC. Unity in centralisation was, however, never achieved, with the regions beginning to establish their own stations. In Ibadan, this was WNTV (Western Nigeria Television Network). WNTV provided a local platform for the arts, televising the early plays of Wole Soyinka.

Broadcasting House, Ibadan.

As we saw at the end of chapter 2, the British state completed its exercise of duplicating itself in the colonies by building structures modelled on existing institutions throughout education, architecture, film and media. Systems that remained dependent on British industrial and commercial partnerships.

Cinema was particularly affected as the film units of Nigeria continued to utilise the services of the OFTVC. The masters of Nigeria’s post-independence film heritage remained in London until the company's decline. As part of the OFTVC collection, Nigeria’s filmographic heritage was sold for the first time. Throughout the course of two more sales and a reincorporation of the company, the material eventually wound up at the Associated Press. Many Nigerian government films were lost and disposed of in this process.

Of the material that remains, it is now kept undigitised; to access it, researchers pay for scans, funding the heritage preservation work, and this allows AP further to exploit the collection at each former colony’s public expense.10 Set against the reality of currently unrealised restitution claims for these films, we find ourselves in a moment of stasis, uncovering deliberate forms of obfuscation that remain, traps set to slow the colonies from retaining and using their power.

Chapter 5

A set of Factions/Truth and the filmstrip

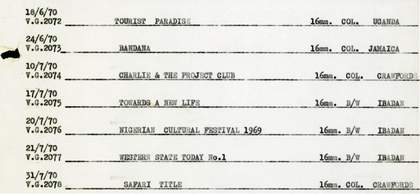

Ibadan, as listed in the real OFTVC catalogues, represented work for either Western Nigeria Television or Western Nigeria’s film unit. These would have been newsreel films documenting the city over time, including various forms of development in the town. Some of these films would have been shown in local cinemas, while a few were projected on vans across the country, spreading awareness of the events in Western Nigeria.

Filmstrips are the earliest form of presentations, serving as a teaching tool that was deployed in Britain and abroad. Its usage is a byproduct of its portability; more accessible and cheaper than film material, filmstrips were widely used in colonial teaching throughout the colonies. Filmstrips came with accompanying manuals that included approximately 40-50 still images, serving as a teaching tool to inform about health, the church, and industrial changes. They were an appendage of the development infrastructure—a small part of the complex that used knowledge as an instrument. As a pedagogical tool, they represent here the didacticism of enforced education; they are representative not only of their method but also of the form of colonial education, which is interventive, bold, and matter-of-fact.

In Wole Soyinka’s memoirs of his early life, he deploys “faction”, a use of fictional reimaginings alongside factual recollections to capture the atmosphere and experience of that time.

In Onyeka’s reimagining of both the film unit and the film strip methodology, she brings cohesiveness to obscure histories and an ambiguous distortion to a didactic method. The reimagined Ibadan Film Unit is a unit whose filmed material draws many seams out of a complicated present. As we look back on the past, we see Ibadan as it is now. An elite space, partially eroded but also of widened accessibility. The film strips lay out the commandments, and then they dispel them, speaking of a collective voice and a collective experience within this faction.

OFTVC Catalogue

Chapter 6

Eroded: Our Peculiar Mess

As you walk around U.I., you can often find obscured views, little passages of light through breezeblocks on campus, where you can catch a glimpse of a new vantage point through the cracks. These structures epitomise the experience of trying to understand the remnants of colonial state institutions. They are vast, and each avenue, walkway and hall leads you towards another understanding or conclusion.

Universities represented one of the final acts of colonial worldmaking—shortly after their founding colonies, which, through extraction, were frozen in time as vestigial components of the metropole became sites of upheaval.

In retreat, Britain removed knowledge in key areas and burned government documents. The second wave of colonialism built and enforced architecture that removed the essence of place to subjugate the environment. Early films made by Britain enforced a colonial methodology that made locals subjects of inquiry. When private companies took over production for those national units, they exploited the colonial relationship to strip former colonies of their filmographic heritage.

Still from a film held at the University of Ibadan’s audiovisual archive.

Ibadan held and still holds visions, memories, and possibilities for the generations that passed through its concrete halls. Creating an archive is not only an act of documentation but also an act of remaking the world by highlighting relations, histories, and lives obscured in the official record.

Towards the end of our time at U.I., after Onyeka’s screening at the university’s film club, we were talking about what we felt was the necessity of duty for a filmmaker. We disagreed; I felt that there was an implicit duty to substantiate a truthful or authentic representation in the context of the paucity of images that deal with postcolonial conditions. For her part, Onyeka said she wasn’t interested in that. She was more interested in the collision of perspectives on how people shape and define experiences.

The traditional voice of the director relegates all other voices to fit a narrative agenda. In Onyeka’s practice, there is a move towards the collective: a shared responsibility on set, a generosity towards freedom of perspective, a refusal to privilege any voice (that even extends impartiality towards the voices of imperialism), through which faction emerges—a blending of stories, memories and feelings that capture experience. To collate these divergent stories is an act of subtle brilliance that imbues art with a collective ethos, producing a political unravelling of colonial knowledge.

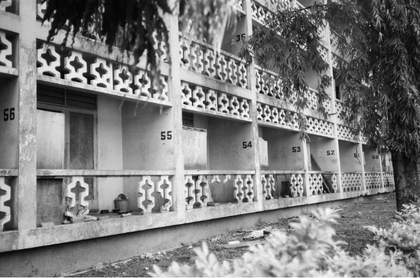

So what of Ibadan? In many ways, it is similar to the life of Adegoke Adelabu, the political leader and thinker from Idaban, who was responsible for the nomenclature of the word, Penkelemesi, from which Onyeka’s film derives its name. U.I. was cut down in its prime. U.I. is trapped in a perpetual condition of funding exigency, shaped by political choices and impositions, affected by the IMF and the legacy of structural adjustment. It is an ivory tower buckling under the weight of its history. Wardrobes are falling out onto balconies as the rooms are overcapacity. Drains spill over in bathrooms. Students remain on courses for seven years instead of four. It is overburdened, yet it remains a place of sanctity, dignity, and precious memories. It is a peculiar mess.

Balconies at the University of Ibadan, Ibadan.