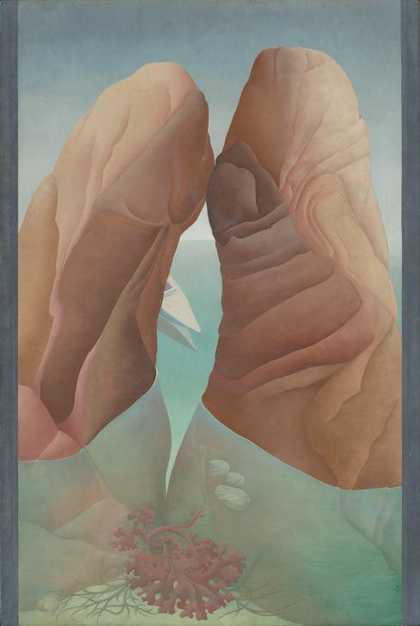

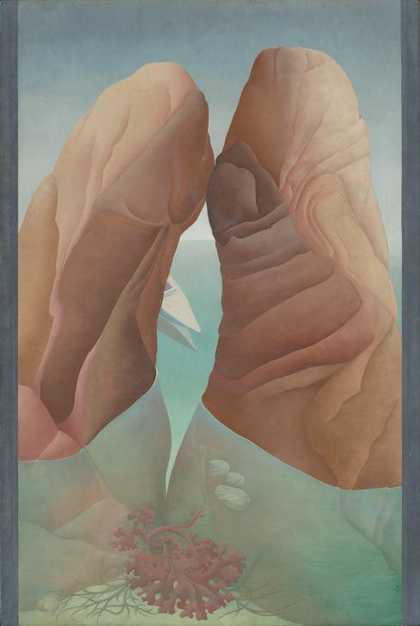

Ithell Colquhoun Scylla 1938. Photo: Tate

Find out more about our exhibition at Tate Britain

Ithell Colquhoun Scylla 1938. Photo: Tate

Ithell Colquhoun (1906–1988) was a visionary artist, an innovative writer and a practicing occultist. Influenced by both surrealism and spirituality, she charted her own course between the worlds of art and magic. In this way, her multi-layered artworks defy conventional creative boundaries. They propose an expanded natural and spiritual universe, and a mystic understanding of sexuality and gender.

Colquhoun was born in Shillong, India, to British parents and raised in Cheltenham, UK. Throughout her life she looked to a range of philosophies from across the world. In her work, Colquhoun reinterprets ideas from spiritual traditions such as the Jewish Kabbalah, Christian mysticism, Egyptian mythology, and Indian Tantra. She also actively engaged with modern occult societies, exploring magical practices and concepts from medieval alchemy through her art and writing.

In the 1930s and 1940s Colquhoun became an important figure in British surrealism. Her work reflects surrealism’s focus on the unconscious mind, irrational subjects and the world of dreams. Colquhoun’s paintings seem to conjure unseen spiritual planes, connecting surrealist methods of automatic picture-making with occult divination rituals. Drawing meaning from these chance experiments, her imagery is often suggestive of bodies and landscapes infused with sacred feminine power. From the 1940s, Colquhoun’s interest in myth and magic brought her to West Cornwall, where she gathered inspiration from ancient sacred sites and Celtic folklore.

After her death, Colquhoun’s work fell into relative obscurity. Recent years have seen a renewed interest in her mystic creative output. This exhibition presents paintings and drawings from throughout Colquhoun’s life, alongside recently acquired material from the artist’s personal archive.

Colquhoun was born in Shillong, where her father worked for the Indian Civil Service of the colonial British Raj. At a young age, she left India and was raised in Cheltenham. Despite her British upbringing she wrote of feeling an enduring connection to her birthplace. She reconciled her mystic inclinations and sense of geographical and cultural displacement through artistic expression and an interest in alternative spirituality.

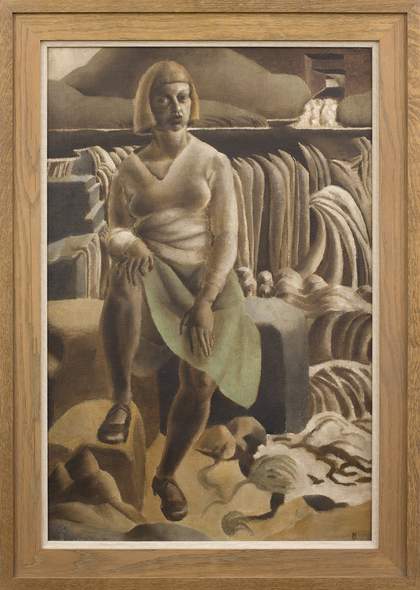

Growing up in the aftermath of the First World War, Colquhoun took advantage of relatively recent opportunities for women to access art schools. She attended Cheltenham School of Arts and Crafts from 1925–7 and studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London from 1927–30. While Colquhoun was at the Slade, the school was at the forefront of an inter-war revival in mural and decorative painting. The young artist studied in the life drawing room as well as making paintings of classical and biblical subjects.

After leaving the Slade, Colquhoun travelled in France and the Mediterranean. She showed her paintings at popular London galleries, including the Royal Academy, Whitechapel Art Gallery and the New English Art Club. Magical societies, which formed part of the modern Occult Revival, also opened their doors to women. Colquhoun made contact with alternative spiritual groups such as the Quest Society and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

Ithell Colquhoun Self-portrait 1929 Ruth Borchard Collection, administered by Piano Nobile © Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans

In the 1930s, Colquhoun engaged with surrealist groups in the UK and France. Surrealism is a transnational artistic and philosophical movement founded in Paris in 1924. Surrealist artists and writers rejected the societal norms they thought had led to the First World War, championing the irrational, the unconscious and the revolutionary.

Colquhoun encountered the work of surrealist artists first hand in 1931, when she briefly lived in Paris. She found the unconventional ideas and meticulously painted imagery of the artist Salvador Dalí particularly inspiring. In the mid-1930s she created an ‘otherworldly’ series of plants in a style she later referred to as ‘magic realism’.

In summer 1936, Colquhoun visited the International Surrealist Exhibition in London, organised by the artist and critic Roland Penrose and the poet David Gascoyne. At the exhibition she attended a famous lecture that Dalí gave while wearing a heavy diving suit. Afterwards, Colquhoun began work on her Mediterranée series of paintings. She considered these dreamlike images to be her first surrealist artworks.

In 1939, Colquhoun joined the Surrealist Group in England. In June of the same year, she held a joint exhibition with Penrose at the Mayor Gallery in London. However, in 1940, the leader of the British surrealists E.L.T. Mesens prohibited members from joining other societies, including occult orders. Colquhoun objected and split from the group.

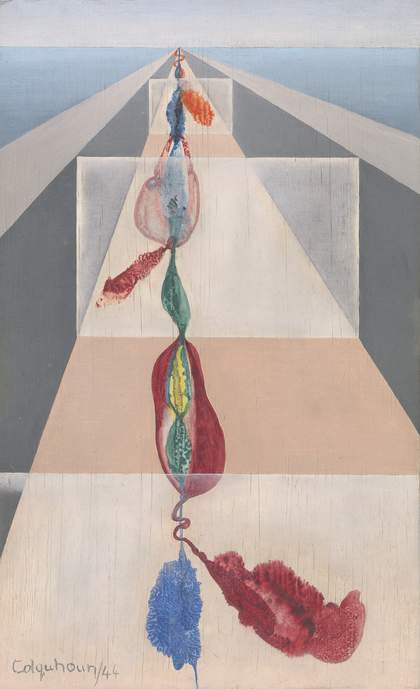

Ithell Colquhoun, Gorgon, 1946, Private Collection © Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans

The Mayor Gallery was an important exhibition space for abstract and surrealist art in London. Colquhoun held a joint exhibition there in June 1939 with the artist and critic Roland Penrose. Many of the paintings in this room were displayed in that exhibition (indicated on artwork labels).

Colquhoun showed paintings from her recent exhibition Exotic Plant Decorations alongside her new Mediterranée series. Salvador Dalí’s ‘paranoic-critical’ approach to artmaking inspired her to channel irrational states of mind, creating images of uncanny and fantastical dream worlds. In works such as Scylla she employed Dalí’s idea of the ‘double image’, in which a single object can be seen simultaneously as two different things. Some works present alternative narratives of sexual power, exploring women’s liberation and the disempowerment of men.

André Breton was a poet and chief spokesperson of the surrealist movement in France. In his First Surrealist Manifesto (1924) he described ‘psychic automatism’: the creation of art without conscious thought.

Colquhoun’s first experiments in automatism occurred just before the outbreak of the Second World War. In the summer of 1939, she visited Breton in Paris and travelled to Chemillieu, France for a gathering of international surrealists. She had been invited by the artists Roberto Matta and Gordon Onslow Ford to explore their new concept of ‘psychological morphology’. They aimed to use automatic methods to interrogate mystical aspects of the human psyche and the external world. Colquhoun would test and reinterpret these ideas throughout the 1940s, in tandem with her occult practices.

Colquhoun began to use automatic, unconscious art-making techniques to explore inner landscapes and the possibility of a multi-dimensional universe. In her 1949 essay ‘The Mantic Stain’ she compared automatism to divination – the perception of future events or forces beyond our earthly senses. The word ‘mantic’ refers to the act of prophecy while ‘stain’ describes the images Colquhoun made through automatic methods.

Many of the paintings in this section were begun using the automatic process of decalcomania. This method involves applying ink or paint to a surface, then pressing another surface against it. The process created abstract images which Colquhoun would develop into finished compositions.

Colquhoun held two exhibitions of her automatic works at the Mayor Gallery in 1947. In March she exhibited paintings and in December she presented drawings. Many of these works are on display nearby (indicated on artwork labels). Colquhoun created them using techniques such as decalcomania and superautomatism, in which the image is begun without conscious thought.

In 1949 Colquhoun published her essay ‘The Mantic Stain’. In it, she describes working from unconscious abstract shapes. She also explains her understanding of ‘psychomorphology’: ‘the discovery by various automatic processes of the hidden contents of the psyche … The principle of these processes is the making of a stain by chance or “objective hazard” to use the surrealist term; the gazing at the stain in order to see what it suggests to the imagination; and finally, the developing of these suggestions in plastic [creative] terms.’

Colquhoun was influenced by the ‘occult revival’, a cultural movement in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries informed by spiritualism, science and colonialism. Members of magical groups combined ancient knowledge, religious practices and scientific ideas in pursuit of spiritual transformation. Colquhoun engaged with the Theosophical Society, which claimed that all faiths are connected by a core spiritual truth. She also followed the teachings and rituals of The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, embracing medieval alchemy, the Jewish Kabbalah, Christian mysticism, ancient Egyptian religions, and Tantric doctrines in Hinduism and Buddhism.

Colquhoun’s ‘magical workings’ are illustrations and diagrams that creatively reinterpret these ideas. Her drawings of ‘alchemical figures’ explore the concept of ‘alchemical union’, the joining of masculine and feminine sexual energies. This process is thought to produce the ‘Divine Androgyne’, a perfect being that transcends gender. Colquhoun also explores same-sex desire and women’s sensual pleasure as paths to achieving enlightenment. In her series Diagrams of Love (c.1939–42) the artist illustrates ideas of sacred sexual union, or ‘sex magic’. Other drawings reference the Tree of Life, a symbol from Jewish mysticism representing hidden connections between human life, nature and the spirit world.

Colquhoun worked on the poems and artworks which make up her Diagrams of Love series between 1940 and 1942. Some are small-scale watercolours of natural phenomena and plant forms. Others consider the alchemical concept of the ‘Divine Androgyne’ through the union of feminine and masculine energies. Heart of Corn is concerned with themes of sacrifice and rebirth, while The Bird or the Egg depicts healing and regeneration. The Tree of Veins draws on the Tree of Life from Jewish mysticism to symbolise interconnections between humanity and the divine. Colquhoun made the drawings primarily for her personal use. Only The Bird or the Egg and Heart of Corn were exhibited during her lifetime.

Colquhoun believed in an interdependent universe of divine energy, perceiving connections between animal, vegetable and mineral worlds. She wrote about the landscape as a living being, inscribed with traces of sacred rituals and ancient spiritual traditions.

From the 1940s, Colquhoun divided her time between London and Cornwall. She rented a studio in Lamorna in 1949 before moving permanently in 1959 to a cottage in the nearby village of Paul. In rural Cornwall she was able to ground her mystical ideas in a specific place.

In her book The Living Stones (1957) the artist explores the Cornish region’s Celtic monuments and folk traditions. Colquhoun cared deeply about the environment, fearing that the sensitive equilibrium between mythic history and the earth was increasingly under threat. She joined various Celtic societies, including the Order of Druids, the Golden Section Order and the Ancient Celtic Church.

Here, Colquhoun’s visionary interpretations of Neolithic monuments are shown alongside depictions of plant growth and eruptive forces. These reflect her interest in natural cycles of energy as elements of the universe’s wider spiritual system.

From the 1940s to the 1970s, Colquhoun explored the concept of the ‘tesseract’, a four-dimensional cube. The artist believed that this theoretical shape could provide access to alternative planes of experience. Colquhoun’s studies led to the expression of divine energies through diagrams, colours and abstract shapes.

In her later career, Colquhoun adapted her automatic practices using new materials. From the mid-1960s, she used an unconscious process of dripping enamel paint to make landscape paintings. Many of these later works depict erupting volcanoes, which in alchemy symbolise a state of magical transformation. In the late-1970s, Colquhoun used the same dripped enamel technique for her visionary tarot deck. This abstract spiritual aid exemplifies Colquhoun’s fusion of artistic and magical practices.

In 1988, Ithell Colquhoun died of heart failure at the Menwinnion Country House Hotel, Lamorna. She was 81. She bequeathed the contents of her studio to the National Trust and her occult works to Tate. In 2019, most of Colquhoun’s works and archive materials were transferred from the National Trust to Tate, bringing together the world’s largest collection of the mystic artist, writer and occultist.

In 1977, Colquhoun produced designs for a set of tarot cards. Tarot decks date back to mid-fifteenth century Europe and are typically used for fortune telling and playing certain games. They usually include 78 pictorial cards divided into the Major Arcana (trump cards) and Minor Arcana (four suits). Some occultists mistakenly thought that the tarot emerged from ancient Egypt. Colquhoun rejected the common spelling, believing ‘Taro’ was a truer reflection of these supposed origins.

Colquhoun’s deck is unique, featuring no pictured figures or symbols. Instead, the artist used dripped enamel paint to create abstract compositions. Rather than providing direct instruction, Colquhoun designed her deck as a meditative tool and spiritual aid. Her cards combine the spontaneity of surrealist automatism with the Golden Dawn’s interpretation of colour theories from Jewish mysticism.

The full deck was exhibited at the Newlyn Art Gallery in 1977. In her 1978 essay ‘Taro as Colour’, Colquhoun recalled: ‘After I had completed the pack, I saw some slides showing nebulae in outer space and the birth of stars. These recalled my designs and confirmed my conviction of their cosmographic function’.