INTRODUCTION

This exhibition explores the intertwined careers of Britain’s most revered landscape artists: JMW Turner (1775–1851) and John Constable (1776–1837).

Constable is best known for painting his native Stour Valley, which lies between the counties of Suffolk and Essex in south-east England. This region came to be called ‘Constable Country’ even in his lifetime. Turner travelled across Britain and Europe in search of his subjects. His paintings depict a vast array of themes, from classical history to steam technology, blending imagination with observation.

Art history loves a rivalry. During their lives, critics pitted the two against each other – Constable’s ‘truth’ versus Turner’s ‘poetry’. Despite their differences, both were seen as highly original painters who challenged artistic norms. Their innovations raised the bar for landscape painting and left a lasting legacy.

250 years on from their births, this exhibition traces their creative development, including moments when their work impacted one another’s.

1. STARTING OUT

Turner and Constable were born just a year apart: Turner in London, the son of a Covent Garden barber, Constable to a prosperous family in the Suffolk village of East Bergholt. As a teenager, Turner earned money alongside his art studies at the Royal Academy. He worked as an architectural draughtsman’s assistant and a watercolour copyist. These jobs developed his skills and exposed him to a broad range of landscape art. Whereas Turner’s father backed his son’s early talent, Constable’s parents were nervous about their son becoming an artist. Nonetheless, their financial support meant that Constable could start his career free from the immediate need to earn money.

Training at the Royal Academy centred on drawing the human figure. It aimed to produce painters of grand historical and mythological subjects. Landscape was far down its artistic hierarchy. But outside the Academy, the genre was becoming hugely popular.

In watercolours from his teens and early 20s, Turner captured the character of places through detailed drawing and unusual compositions. The Lake District and Wales were popular tourist destinations. As subjects for art, they were likely to sell well. With Turner’s wanderlust and business sense, it is no surprise that we find him picturing these locations. In 1806, Constable took a seven-week tour to the Lakes. One of his Lake District paintings prompted his first mention in the art press.

2. IN THE OUTDOORS: CONSTABLE AND THE OIL SKETCH

Constable started to use oil paints outdoors in 1802. Travelling back to Suffolk from London for the summer, his aim was to achieve a ‘pure and unaffected representation … with respect to colour particularly’. He described making his outdoor sketches ‘in the lid of my [paint] box on my knees’.

By 1810, he had mastered the art of the oil sketch and had begun to create the body of work that would serve him in the studio for decades to come. It would also become one of the most defining and celebrated aspects of his output. Many of the sketches here are notable for their vibrant colouring and their atmospheric effects. They reflect Constable’s concerted effort to capture different times of day.

Painting outside is inherently challenging: gusts of wind, rain showers, insects, passers-by or even curious animals can hamper the process. Under these conditions, rapid brushwork was necessary. Constable’s mastery of this skill and his economic application of multiple colours within a single brushstroke are evident in his sketches. He also adopted the same techniques when making sketches in the studio to help him work out his ideas for larger paintings.

The results were daring. At exhibitions, compared to the smoothly finished surfaces of others’ work, Constable’s appeared freely and loosely painted. To some, they were ‘crude’. Others saw in them ‘originality and vigour’.

3. ‘NO SMALL WONDER’: TURNER IN THE ALPS AND ITALY

Travel throughout Britain and Europe was the backbone of Turner’s art. Two locations particularly sparked his creativity: the Alps and Italy. He saw them first through the eyes of other artists, since the Napoleonic Wars restricted travel to Europe until 1815.

A pause in hostilities in 1802 meant that the 27-year-old Turner could finally go abroad. Journeying through Paris and exploring its art collections, he made his way to the Alps. His tour took in France, Switzerland and a short excursion to Italy’s Val d’Aosta. It did not disappoint. Turner’s experiences of the region’s magnificent glaciers, peaks and passes were revelatory. They sharpened his interest in the ‘sublime’ – making pictures that generated the strongest possible emotion, close to terror. Later, he described this tour as ‘no small wonder’.

When peace in Europe was restored, Turner could finally explore Italy. By this time, he was an established artist of 44. Despite having hardly been there, he was already associated with the country thanks to his depictions of its landscape and scenes from classical literature. His extensive preparations for the six-month trip included reading guidebooks and making sketches of other artists’ views of key sites to visit. Turner was hungry for Italy’s scenic riches. He filled 23 sketchbooks, coming home with imagery that would underpin decades of finished paintings.

4. MAGIC ARRANGEMENTS: TURNER’S WATERCOLOURS

Watercolour is a vital part of Turner’s story. From the moment he received a set of watercolours as a child, this medium played an important role in his career. Associated in the 18th century with amateur artists, it was regarded as a lesser medium than oil paint. Combining innovative handling and highbrow subject matter, however, Turner raised its status. He chose to display his watercolours close-framed in gilt surrounds, just like oil paintings.

Turner’s early exhibited watercolours first alerted critics to his outstanding talent. There were sceptics, who called them ‘experimental and gaudy flimsies’. But there was a general astonishment and curiosity about his techniques. ‘No man has ever thrown such masses of colour upon paper’, wrote one critic. Another mused: ‘blended and sometimes delicately contrasted as [Turner’s] colours are – the effects are exquisitely tender, but not without sufficient force, from a certain magic arrangement, a graphic secret of his own.’

An account of Turner at work described how he ‘poured wet paint’, then ‘tore … scratched … scrubbed at [the paper] in a kind of frenzy’ until ‘as if by magic’, a picture came into focus. Turner could certainly dash off images with flair, but the watercolours here attest to a more meticulous process. For some, he used a brush made of a few squirrel hairs. In Turner’s eyes, these finely wrought watercolours were waypoints in a process – he made most of the works in this section to be reproduced as prints

5. TURNER’S STUDIO

From 1799, Turner owned premises at the junction of Queen Anne and Harley Streets in London. Here he had his purpose-built studio, lodgings and a public gallery. He installed a peephole to spy on visitors to the gallery before deciding if he wanted to greet them. On display here are the kinds of things you might have seen in Turner’s studio.

Turner was a notoriously private man and his studio a private place. If lucky enough to be invited in, you would find yourself surrounded by stacks of paper, paintings in progress, a rainbow of pigment in jars and an array of sketchbooks. One of his housekeeper’s seven Manx cats might be prowling, leaving paw prints on Turner’s pictures. Anecdotes from those who saw Turner at work tell us of sheets hanging on lines to dry, having been drenched in colour. This was a place of experimentation where Turner could set his imagination free.

The studio was where he cultivated ideas gathered outdoors. Occasionally, he combined his two favourite activities: painting and fishing. But mostly he preferred the speed of using pencil in sketchbooks. These became a visual reference library in the studio. He would often return to a sketch years or decades after first making it.

At the end of Turner’s life, his studio and gallery were in bad repair. A canvas had been cut for a cat-flap, another patched the leaky roof. Today’s careful conservation and framing is a far cry from the creative chaos of the studio Turner left behind.

6. CONSTABLE: FIELDS AND SKIES

‘I live wholly in the fields and see nobody but the harvest men’, wrote Constable in August 1814. That summer, he started making large, finished paintings outdoors – practically unheard of at the time. The fields in his native Stour Valley became his studio. In his search for ‘truth’, he removed the literal distance between painting process and subject.

Constable’s finished paintings were not spontaneous responses to the landscape, however. Behind them lay extensive preparatory work – oil sketches and pencil drawings in sketchbooks. And, like Turner, Constable often referenced work by celebrated past masters. But where subtle, subdued tones were the norm, he was determined to paint nature in its true hues. His greens and yellows are as bright as they might appear on a sunny day.

Some critics still found his textured brushwork ‘crude’. But his paintings were praised for their ‘sparkling sun-light’, ‘freshness’ and a ‘character of truth’. Constable’s rural realism was selective, however. His work gives little sense of the agricultural unrest and hardship of the period.

In 1819, Constable rented a house in Hampstead, then a village outside London. There he started making rapid oil sketches of clouds, a practice he called ‘skying’. These works reflect Constable’s keen interest in weather. His preoccupation with the sky is evident in his 1823 depiction of Salisbury Cathedral.

7. SIZING UP: THE EXHIBITION

For Constable, Turner and their contemporaries, the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition was where artistic reputations were made and lost. It was a mass shop window with a fashionable audience of potential buyers and patrons. Walls were crammed with pictures hanging frame to frame. For artists, the challenge was making art that stood out from the crowd.

Turner soon learned ways to command attention through scale and increasingly intense colour. His choice of subjects showed off his versatility, from ancient history to modern technology. Critics were divided. The same painting might be praised by one as ‘transcendent’ but condemned by another as ‘not true to nature’.

In the 1810s, Constable was struggling to get noticed. A friend told him candidly that his paintings did not ‘solicit attention’. This spurred an important development, the making of large-scale paintings known as ‘six-footers’. When the first of these, The White Horse, was exhibited in 1819, it prompted the first comparison between Constable and Turner. According to one reviewer, Constable’s White Horse had ‘none of the poetry of Nature like Mr. Turner, but … more of her portraiture’. The painting also led to Constable’s election as an Associate Member of the Royal Academy. Scaling up had paid off.

Turner and Constable’s paintings were also exhibited beyond London, for example in Manchester and Birmingham.

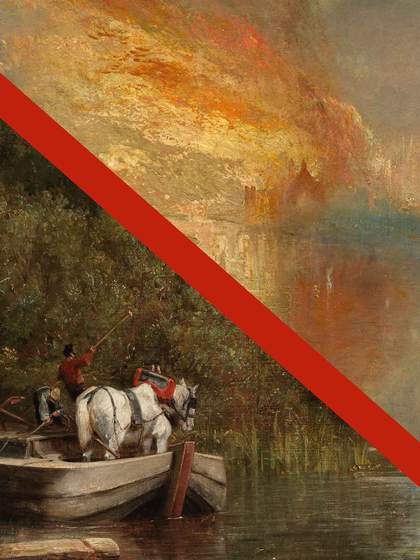

8. FIRE AND WATER

In the mid-1820s, Constable referred to Turner in a letter as ‘he who would be lord of all’. Turner was certainly the biggest name in landscape of all media – oil painting, watercolour and print. At this point, Constable had enjoyed great success in France but acceptance by British artists eluded him. Constable’s day finally came in 1829. Royal Academicians voted him into full membership. Turner paid a visit especially to congratulate him.

Two years later, they came to blows. Artists hated being hung next to Turner in the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition because his paintings ‘caught your eye the instant you entered the room’. In 1831, Constable took up the challenge. As a member of the committee responsible for placement of works in the exhibition, he hung his Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows next to Turner’s Caligula’s Palace and Bridge. The arrangement gave Constable’s own painting prime position.

At a dinner party, Turner apparently came ‘down upon him like a sledge-hammer’. One onlooker recalled dramatically that Constable ‘wriggled ... like a detected criminal’.

The art critics delighted in the contrast. Perhaps this was part of Constable’s plan. They cast the pair as opposing natural forces: ‘fire and water’, Turner ‘all heat’ to Constable’s ‘humidity’. Acknowledging the power of their paintings, reviewers also complained that both artists’ techniques were excessively bold.

John Constable

Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows (exhibited 1831)

Tate

9. LATE CONSTABLE: BEYOND ‘CONSTABLE COUNTRY’

The late 1820s was a time of personal loss and professional gain for Constable. His wife Maria died in 1828, leaving him a widowed father to their seven children. The following year, he was elected as a Royal Academician. He was finally receiving official recognition from his artist peers.

Determined to prove his versatility and ambition, Constable varied the subjects of his six-footers. Choosing settings in Brighton and London, away from his home turf in the Stour Valley, he tackled coastal storms and grand neoclassical architecture. By now, most critics recognised his uniqueness. They called his work ‘vigorous’ and ‘free and bold’. With his profile raised, detractors fixated on his use of white highlights, known derisively as Constable’s ‘snow’.

Turner became alert to the competition. Just before the 1832 Royal Academy annual exhibition opened, he added an attention-grabbing red brushstroke to his own work hanging close to Constable’s The Opening of Waterloo Bridge. Constable retorted: ‘[Turner] has been here and fired a gun’. But was it an act of artistic aggression? Turner’s red daub might have been a gesture of both rivalry and kinship – perhaps the biggest compliment and expression of acceptance Constable could have received. And, as the intensity of his later works shows, Constable committed to a bolder, more daring way of painting.

John Constable

The Opening of Waterloo Bridge (‘Whitehall Stairs, June 18th, 1817’) (exhibited 1832)

Tate

10. AIRY VISIONS: TURNER’S LATE WORK

Turning 60 in 1835, Turner could have rested on his financial position and standing then slowed down. He did no such thing. Instead, he continued innovating and astonishing his viewers with the same unwavering energy as always. 1835 saw him take one of his most extensive and taxing European sketching tours. He continued to travel abroad for another decade.

Turner remained highly engaged in the art world of the 1830s and 40s. He made topical paintings of present-day subjects, including a fire that destroyed the Houses of Parliament. Keeping up his links with the print trade, he was commissioned by publishers to make watercolours of places he had not visited, including India. Favourite locations like Venice and the Swiss Alps came back into focus with repeat visits.

His work continued to attract both ferocious ridicule and profound appreciation. Rival or not, Constable was among those who admired Turner’s 1836 Royal Academy exhibits. That year he wrote, ‘Turner has outdone himself – he seems to paint with tinted steam, so evanescent, and so airy.’

In 1842, Turner made two works that encapsulate the breadth of his late vision. In the oil painting Snow Storm - Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth we experience his intensifying fascination with both the sea and modern technology. The Blue Rigi sees Turner scale new technical heights in watercolour, the medium that launched his career. Both continue his lifelong exploration of nature’s power, be that its terrifying force or awesome beauty.

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Blue Rigi, Sunrise (1842)

Tate

11. LANDSCAPE AND MEMORY

Constable died in 1837, aged 60, and Turner in 1851, aged 76. Both remained intellectually and artistically active in their last years, though illness became a more frequent obstacle.

The intense atmosphere of Constable’s late work reflects his inclination to melancholy. In 1835, he received the warmest critical reception of his career, calling it ‘the best year of my life – as to my being “liked”’. But, he added, the ‘happy years are gone’. He found solace in painting: ‘my canvas soothes me’. The results are often far from peaceful, reverberating with restless energy.

After years of showing reworked canvases, in 1850 Turner exhibited new paintings. Their subjects, drawn from classical mythology, were now unfashionable, but his way of painting was unparalleled. Critics acknowledged him as a ‘great master’ while remarking on the ‘eccentricities’ of his old age: ‘it would seem as if Mr. Turner had possessed in youth all the dignity of age to exchange it in age for the effervescence of youth’.

The artists both looked backwards to create new works out of old. Two unfinished paintings are prime examples of this tendency. Both are based on earlier compositions they had shared in printed manifestos on the possibilities of landscape painting. Stoke-By-Nayland is a last investigation of light and shade in nature, Constable’s lifelong preoccupation. Norham Castle shows the evolution of Turner’s vision for landscape. Despite their apparent differences, these late works reflect their makers’ drive to convey the spirit of a place and their fascination with painting light.

12. LEGACY: ARTISTS TODAY

In this film, artists explain how Turner and Constable have guided their own artistic journeys.

He’s one of my heroes. He made nature a real subject, which it had not been before. The light in Constable’s paintings is right – it doesn’t feel artificial. His painting has broken colour, broken marks, it’s not smooth. This gives it an immediacy and brings it closer to our own experience of being outside in the country.

Bridget Riley on Constable

The abstraction you get in Turner, the tumultuousness of the paint handling, that’s what particularly excites me about it still. It went through his body, a real feeling for paint. The magic, the tumoil in the work, it’s attracted me for a long, long time.

Frank Bowling on Turner

I feel a real affinity to Turner’s impulse to travel and truly experience the dynamics of nature. I love the spontaneity and power of Turner’s sketchbook drawings. You can absolutely feel the weather .

Emma Stibbon on Turner

His paintings seem very solid, made of the same stuff of the earth, and of my life. I find him constantly on my shoulder telling me to be not so fanciful, not such a berk, not such an artist really. But to be a person or a thing of the world.

George Shaw on Constable