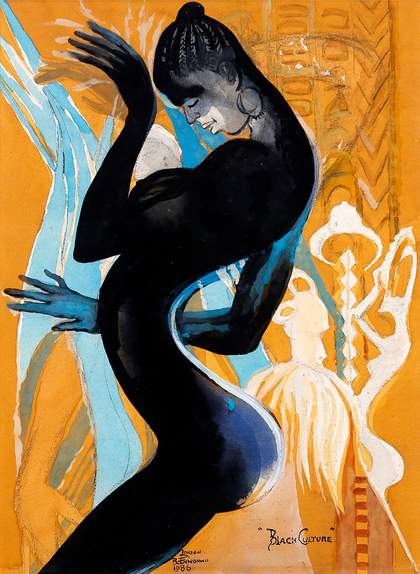

Benedict Enwonwu Black Culture 1986 Lent by Kavita Chellaram 2025 © The Ben Enwonwu Foundation

Introduction

Nigerian Modernism explores the rise of modern art in Nigeria before and after national independence. The exhibition foregrounds artists who advocated for political and creative freedom during the 20th century.

Nigerian modernism was not a single movement, but a variety of responses to the country’s shifting cultural and political identity. Nigeria was established as a British colony in 1914. By this time, prosperous African kingdoms and societies had been profoundly altered by decades of military campaigns and colonial exploitation. Under British rule, artists continued to find innovative ways to express their own ideas, histories and imaginations. They embraced and rebelled against the colonial education system. Some created their own art societies and curriculums, while others travelled abroad in search of professional opportunities.

Throughout Nigeria, artists were influenced by Pan-Africanism and European art forms. They also drew inspiration from local cultures. Artistic and religious traditions from the region’s many ethnic groups – including Fulani-Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba people – met Christian and Islamic practices.

In 1960, Nigeria gained independence from Britain. New artistic and literary clubs were founded across the country, providing spaces to explore the intersections of art, poetry and performance. During this period, Nigeria experienced an economic boom, but it also faced a devastating civil war. In the aftermath, artists established new visual languages in their search for a new postcolonial identity.

Nigerian Modernism follows developments in Nigerian art at home and abroad from the 1920s to the 1990s. Each room highlights the different artists, societies and schools who carved out independent visions for what modern art in Nigeria could be.

Figuring Modernity

The exhibition explores the diverse forms of figurative portraiture and sculpture associated with the emergence of modern art in Nigeria. From 1914, Nigeria was governed by the British through a system of indirect rule. Indigenous rulers and newly appointed chiefs acted as intermediaries between the Nigerian people and the British administration. Schools were designed to train future civil servants who would uphold this system. Formal arts education was not included. Christian mission schools, meanwhile, pressured Nigerian converts to destroy traditional religious objects and encouraged the depiction of Christian stories.

In 1923, Nigerian artist Aina Onabolu introduced a new art curriculum in several secondary schools in Lagos. The syllabus was inspired by the art schools he had attended in London and Paris. It included lessons on perspective, colour theory and easel painting. He saw European academic painting as a tool for Nigerians to express their identities on their own terms. Most of the artists in the first room of the exhibition received this European-style art education.

Indigenous art forms – such as bronze casting, wood carving and mural painting – continued to be taught through apprenticeships. Some Nigerian artists developed and drew from these techniques. Others used European-inspired portraiture to criticise British Imperial rule and to represent the daily realities of life in Nigeria.

Ben Enwonwu: Ghosts of Tradition

Ben Enwonwu was the first African modernist to gain international recognition. He created a new visual language for modern Nigerian art, combining his training in Igbo sculpture with his knowledge of masquerade and European artistic traditions.

Born in 1917, Enwonwu was inspired artistically by his father, a well-known sculptor who created art for religious shrines in their hometown of Onitsha. Enwonwu enrolled at the Government Art College in Ibadan, south-western Nigeria. Later, he received a scholarship to study at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, where he experienced early commercial success.

In 1946, Enwonwu met Senegalese poet and politician Léopold Sédar Senghor. Senghor introduced him to the concept of Négritude, an anti-colonial literary movement that advocated for the importance of Black and African cultural heritage. Although Enwonwu worked for the Nigerian colonial government as an art advisor from 1948, he also believed that colonialism limited artistic expression. At the First International Congress of Negro Writers and Artists in Paris, in 1956, he declared: ‘I know that when a country is suppressed by another politically, the native traditions of the art of the suppressed begin to die out … Art, under this situation is doomed.’ He navigated these contradictions throughout his career.

Enwonwu explored a wide variety of themes and styles in his work, moving between landscape and portraiture, and creating symbolic images of African dances, cultural rituals and masquerade performances. He consistently described himself as a sculptor, making connections between his modern art practice and the sculptural traditions he inherited from his father.

Ladi Kwali: Of Soil and Stone

Ladi Kwali transformed traditional Nigerian pottery with her use of high-fired glazed stoneware. She was born in 1925 in the Gwari region of northern Nigeria, where pottery was traditionally made by local women. Her aunt taught her to make pots and other vessels using the coiling method. She looped ropes of clay in concentric circles to build up the walls of the pot, before beating them into a flat, even surface. Her work earned her a reputation as a highly respected artist, prompting local ruler, the Emir of Abuja, to commission her work for his palace.

In 1954, Kwali became the first woman trainee at the Pottery Training Centre (PTC) in Abuja. British potter Michael Cardew, who ran the centre, invited Kwali to join after seeing her work at the Emir’s home. At the PTC, she learnt how to throw pots on a wheel and work with different glazes. She continued to make Gwari-style coiled water pots but used stoneware clay, which is fired at high temperatures in a kiln, rather than earthenware, which is more suited to traditional open-air firing.

Drawing into the clay using sharpened palm and bamboo, Kwali created designs that reference local folklore. Mythical scorpions, lizards, fish and snakes animate her vessels.

The incised lines are filled with white porcelain, which glows under the thick glaze. As Kwali experimented with new forms, she began to make vessels that no longer served a domestic function but existed solely as works of modern art.

New art, new nation: The Zaria Art Society

The Zaria Art Society was founded at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology (NCAST) in Zaria, a city in the north-west of the country. The college was modelled on the British educational system. Its courses largely disregarded African art and cultural traditions. In 1958, a group of art students came together to rebel against the limited, Eurocentric curriculum. They championed the Pan-Africanist agenda to recover disappearing African cultural heritage as a means of shaping the future art of the nation.

In October 1960, Nigeria achieved independence from Britain. That month, artist Uche Okeke wrote ‘Natural Synthesis’, a manifesto for the Zaria Art Society. His desire to create ‘a new culture for a new society’ relied on the synthesis – or merging – of foreign and Indigenous artistic traditions. Okeke declared: ‘Young artists in a new nation, that is what we are! We must grow with the new Nigeria and work to satisfy her traditional love for art or perish with our colonial past … This is our renaissance era!’

After graduating, many Zaria Art Society members moved to Ibadan, a university town in south-western Nigeria. There, they co-founded the Mbari Artists and Writers Club in 1961 alongside German publisher Ulli Beier. Located in a former nightclub, it featured a library, gallery, theatre and Lebanese café. It was also the home of the literary journal Black Orpheus. The club nurtured an international community of artists, writers and performers.

Eko

Lagos – also known as Eko, its precolonial name – is Nigeria’s most populated city and a major port. The city is a vital point of cultural and economic exchange in Nigeria. Throughout the 20th century, it was a hub for internal migration, Christian missionary activities and the resettlement of ‘returnees’, formerly enslaved people who had returned from Europe, the Americas and elsewhere in Africa.

The anticipation of Nigerian Independence in 1960 brought about rapid urbanisation. People from across the country travelled to Lagos in search of new opportunities. Government spending increased during this period of economic prosperity and the arts thrived. The architectural landscape of Lagos was transformed by Nigerian and British architects. They adapted international modernist styles to respond to the country’s tropical climate and unique architectural heritage. Highlife – a music genre that blends Latin, European and African-diasporic musical styles – became hugely popular in Lagos during the 1950s and 1960s. The hybrid style of highlife reflected the cosmopolitan nature of the city.

Arts education became more widely accessible at this time. A new generation of artists, many associated with Nigeria’s royal sculpture guilds, explored Pan-African approaches to modernist sculpture. Publications such as Nigeria Magazine closely followed these developments. With its economic dynamism, highways and high-rise buildings, and blend of religions, ethnicities and cultures, Lagos became the archetypal modern African city.

Forest of a Thousand Spirits: New Sacred Art Movement

Established over 400 years ago, the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Groves are dedicated to Osun, the Yoruba river goddess associated with fertility. They are located just outside the city of Osogbo, along the Osun River in south-western Nigeria. By the late 1950s, the main shrine to Osun had fallen into disrepair. Local priests invited Susanne Wenger, an Austrian-born artist who had become a Yoruba high priestess, to help restore it. She brought together a group of local artists to work with her on this project, which developed into the New Sacred Art Movement.

The movement’s members were guided by their devotion to orisa (Yoruba deities) and by a deep spiritual bond to the land. Artists, including Adebisi Akanji and Buraimoh Gbadamosi, used their knowledge of carpentry and cement sculpture to create new shrines and artworks throughout the groves. Most were constructed in natural forest clearings, helping prevent the nearby city from expanding into the forest. In recognition of its cultural and spiritual significance, the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Groves were declared a national monument in 1965 and inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005.

Beyond their work in the groves, artists also produced batik textiles inspired by Yoruba cosmology. They believed art should have a religious function and saw creativity as part of their spiritual life.

Festival of the Gods: The Osogbo School

In the 1960s, Osogbo was a thriving town with bustling marketplaces selling Yoruba textiles and beads. Locals participated in Christian and Muslim celebrations alongside traditional Yoruba ceremonies. A festival dedicated to the river goddess Osun was among the most spectacular. Orisa deities were also celebrated in popular theatrical performances. Osogbo-born playwright Duro Ladipo toured his opera Oba kò so (The King Did Not Hang) around the region. It told the story of Sango, an ancient ruler of the old Oyo empire who became the god of thunder and lightning.

From 1962, Ladipo hosted several art workshops at his Popular Bar, led by international artists including Georgina Beier. The workshops were organised by the new Mbari Mbayo Club, an outpost of the Mbari Club in the nearby city of Ibadan. Unlike the Ibadan organisation, which mostly catered to university graduates, the Mbari Mbayo Club aimed to become a cultural movement for local people with no formal education in visual art. Performers in Ladipo’s theatre troupe became the core members, receiving training in techniques such as printmaking, painting and textile design.

The group became known internationally as the Oshogbo School. Their work celebrated Yoruba beliefs, folklore and the magical realism in popular fiction by authors such as Amos Tutuola. Together with the renewal of the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Groves, they helped to establish Osogbo as a centre for the Yoruba religion.

Signs of Life: The Nsukka School

The Nsukka School developed in the early 1970s at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, in the aftermath of the Nigerian Civil War (1967–70). After a military coup and a series of anti-Igbo massacres in northern Nigeria, many

Igbo people fled their homes, returning to their ancestral lands in the south east. In 1967, the area declared independence from Nigeria, becoming a secessionist state called the Republic of Biafra. The war that followed led to the deaths of over a million south-easterners, mainly Igbo people, after the Nigerian army targeted civilians and military blockades created a famine. In 1970, Biafra surrendered and was reintegrated into Nigeria.

After the war ended, Igbo artist Uche Okeke was appointed head of Nsukka’s fine art department. Expanding on his idea of ‘natural synthesis’, he encouraged students to reclaim Indigenous cultures and create art that spoke to their local environment. He drew attention to uli, a disappearing form of communication that had been practiced by Igbo women for centuries. Uli designs were meant to be temporary, painted on bodies and walls. They comprised both abstract shapes and symbolic drawings representing organic forms, everyday objects and celestial bodies.

A group of art students and professors of different cultural and ethnic backgrounds joined Okeke. Some combined uli with nsibidi, an ancient graphic communication system developed by Ejagham people of the Cross River region. Their aim was not simply to revive Indigenous art forms but to apply them in a modern context. Their work commented on the social, political and economic state of Nigeria and its struggles as a postcolonial nation. The group had a lasting impact on the curriculum at Nsukka, influencing successive generations of artists.

Come Thunder

Christopher Okigbo is celebrated as one of Nigeria’s most influential poets. He also worked as a librarian at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, where he helped to found the African Authors Association.

Now that the triumphant march has entered the last street corners,

Remember, O dancers, the thunder among the clouds…

Now that the laughter, broken in two, hangs tremulous between the teeth,

Remember, O Dancers, the lightning beyond the earth…

The smell of blood already floats in the lavender-mist of the afternoon.

The death sentence lies in ambush along the corridors of power;

And a great fearful thing already tugs at the cables of the open air,

A nebula immense and immeasurable, a night of deep waters —

An iron dream unnamed and unprintable, a path of stone.

The drowsy heads of the pods in barren farmlands witness it,

The homesteads abandoned in this century’s brush fire witness it:

The myriad eyes of deserted corn cobs in burning barns witness it:

Magic birds with the miracle of lightning flash on their feathers…

The arrows of God tremble at the gates of light,

The drums of curfew pander to a dance of death;

And the secret thing in its heaving

Threatens with iron mask

The last lighted torch of the century…

Christopher Okigbo (1932–1967)

Uzo Egonu: Painting in darkness

A Nigerian artist living in postwar Britain, Uzo Egonu dedicated his work to themes of nationhood and belonging. Born in 1931 in Onitsha, south-eastern Nigeria, Egonu began painting and drawing at a young age and received early encouragement from fellow Onitsha-born artist Ben Enwonwu. He moved to the UK as a teenager and later enrolled at Camberwell College of Arts and Crafts in London.

The devasting loss of life during the Nigerian Civil War left a deep impression on Egonu as an Igbo artist. Although he only briefly returned to Nigeria once in 1977 for the cultural festival FESTAC, he remained deeply invested in the struggles of the emerging independent nation.

In his work, he blended the figurative and the abstract, fusing the aesthetics of European modernism with traditional Igbo sculpture and uli wall art. Egonu became interested in etching, exploring what he described as ‘the poetry of lines’. However, this process exposed him to toxic fumes and by 1979 he had lost much of his vision. During this period, which he described as ‘painting in darkness’, he created some of his most vibrant and expressive paintings – Stateless People. His work caught the attention of artists in the Nsukka School including Obiora Udechukwu, who described Egonu as ‘perhaps Africa’s finest painter’.

Although Egonu’s work was embraced by the British Black Art Movement later in his career, he continued to refuse categorisation. He fashioned a radically independent position as a leading Nigerian artist working in the global diaspora.