Pablo Picasso, The Three Dancers 1925

Tate. © Succession Picasso / DACS 2024

Introduction

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (born Malaga, Spain, 1881–1973) is one of the best-known painters of the twentieth century. Over the course of his long career, he produced works in many different styles such as cubism and neoclassicism, which have come to mark turning points in modern art. Because of his importance, Picasso’s work and public persona continue to generate vigorous debate, with artists and art historians returning to his work time and time again.

One of the most famous works in the Tate collection – Picasso’s The Three Dancers 1925 – was created 100 years ago. To celebrate this centenary, Tate has invited contemporary artists Wu Tsang and Enrique Fuenteblanca to make an exhibition that responds to it. Rather than take a conventional historical approach, they approach exhibition-making as a performance itself, by ‘staging’ Tate’s entire Picasso collection. We are invited to step onto the stage with these works and to consider the meaning of performance through Picasso: how he created a public persona and transformed the way we look at art, profoundly influencing how artworks are collected and encountered today. Acknowledging both his innovations and their complexities, this exhibition looks beyond the myth of Picasso as a solitary genius, to examine his practice within wider contexts and communities: artistic exchanges, acts of borrowing and the historical conditions that shaped it.

Wu Tsang is an award-winning visual artist and director of film and theatre. Her film installation A day in the life of bliss 2014 is on long term loan to Tate collection.

Enrique Fuenteblanca is a writer, artist and curator. He regularly contributes dramaturgical texts for contemporary dance and flamenco. He is an ongoing collaborator for Wu Tsang.

Look out for our special QR codes labels throughout the exhibition. These offer further information about Picasso’s work, highlighting interesting topics and the ongoing research Tate does into the collection.

Performing Picasso

Picasso cultivated and performed a public persona that was part ‘genius’ and part ‘outsider’. This persona helped to shape our idea of the ‘Artist’ as a solo creative, a prolific master and a mysterious marginal figure in society.

Tsang and Fuenteblanca see theatrical techniques incorporated into Picasso’s persona. It is evident in the way he performed his dramatic brush strokes for the camera, and in the way he crafted his own image through appearances in magazines and films. Picasso’s understanding of performance was informed by his fascination with theatre, dance and popular forms such as circus and flamenco. He borrowed from these forms and applied them as tools in his own work.

To grasp Picasso beyond his mythology, it is important to understand how he used these tools from performance. We can also understand how he related to the world around him, placing his work in dialogue with the fundamental questions of our time.

Performativity: Doing Things with Art

Theatre Picasso invites us to look beyond the pictures on the walls and consider what the artist does with his art and actions. Here the concept of ‘performativity’ is useful.

Performativity has different meanings, but an important one is the way in which words and actions can effect change, transform, or undo states of being. An example from philosopher JL Austin, is the utterance ‘I do’ when it is performed in the act of marriage. Performativity also plays a role in understanding a range of identities including class and gender.

If we look at Picasso’s work through the lens of performativity, we find many interesting examples of how the artist plays with the power of words, actions and images, and how they impact our perception of art. We might also ask, as his audience, how do we play our role?

Picasso organised his first retrospective himself in 1932 at Galeries Georges Petit in Paris. He took personal control of arranging the artworks, choosing to mix styles and periods. Tate collection work Head of a Woman 1924 can be seen resting on a chair in the photograph shown in the exhibition, documenting this retrospective.

Pablo Picasso

Head of a Woman (1924)

Tate

Collecting Picasso

Picasso’s presence in museums around the world attests to his central role in shaping modern and contemporary art. Tsang and Fuenteblanca have staged this exhibition showcasing Tate’s collection of Picasso artworks. In doing so, they invite us to consider how and why museums collect what they collect. What is shown and what is not? If we look at Tate’s Picasso collection in its entirety, what does it reveal?

Museums themselves, including Tate, are increasingly reevaluating the logic of their own collections. To exhibit Picasso today is also to confront his legacy, including its contradictions. Picasso’s work draws out complex questions about borrowing from other cultures, for example, or about invention and originality. These questions, in turn, give us tools to think about ourselves and how we organise contemporary institutions.

A Terrible Theatre: Scene, Obscene

Through acts of transgression, the use of ‘obscenity’ in theatre is as ancient as the artform itself. Performance has traditionally given us permission to play with topics and behaviours otherwise considered taboo, as a way to reflect on society. Picasso frequently worked with the obscene in both intimate and overtly political ways. Within his sketches of the theatre and brothels seen in the exhibition, we see him use architectural stages to frame obscene imagery. In this way, Picasso performed the role of a tragicomic artist by bringing onto the stage things that some may not wish to see.

Lost Body

Early in Picasso’s career he saw art from across Africa and the Pacific Islands at the Ethnographic Museum of the Trocadéro in Paris, and this became a strong influence on his practice. He had a complex relationship with these cultures and he freely appropriated from the artworks of colonised peoples, which some have interpreted as a form of theft.

He also celebrated this art and identified with oppressed peoples around the world. An example of this solidarity is Picasso’s relationship with the poet and Martinique politician Aimé Césaire. Césaire was one of the founders of the Négritude movement, a group of Black writers in France in the 1930s, working to resist colonialism. In 1949 Picasso and Césaire worked together on the book Lost Body, exhibited here, with Picasso illustrating Césaire’s poetry.

The Painter and the Model

Among the most significant themes addressed by Picasso is that of the painter and the model. For him, the impossibility of truly capturing the model becomes a dramatic impulse, relentlessly driving his work. Picasso's numerous portraits of his various lovers and models reflect the constant stylistic transformation throughout his life. However, his paintings of the model reveal something else: how this obsession intertwined with his possessive relationship with women and his unsettling view of them. Picasso does not conceal this idea: the eyes of the portrayed model often return the viewer’s gaze, confronting us in the act of looking.

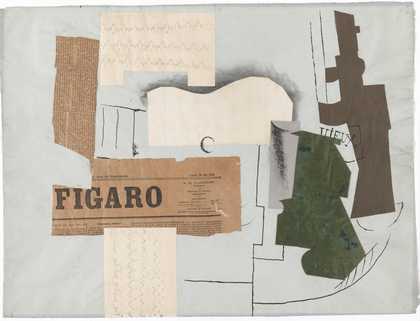

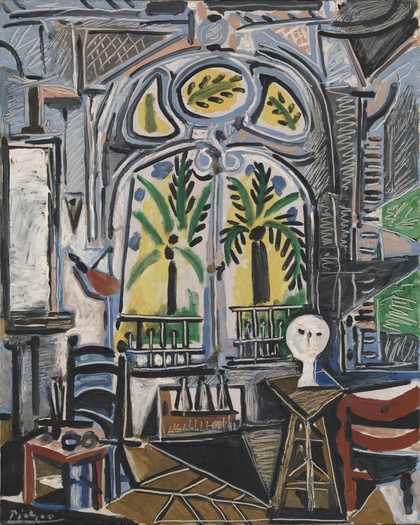

The Artist’s Studio

Still life and studio subjects provided Picasso with a space for formal experimentation. He described his painting as ‘a sum of destructions’. His words have often been interpreted as an attempt to destroy traditional forms of representation. His drift from cubism to classicism, or his use of techniques such as collage, were ways of breaking into an artistic field in which the supremacy of some styles and movements was disputed. At the same time, the studio is the artist's intimate space. That is why his paintings of still lifes and studios reveal emotional states: war and darkness through still lifes dominated by skulls and painted in dark colours, or the emptiness of the artist's studio in exhibited work The Studio 1955, made shortly after the death of his great friend and rival Henri Matisse in 1954.

Pablo Picasso

The Studio (1955)

Tate

Animals, War and Violence

Animals held important symbolic value in Picasso’s work. Following the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War, his Dove 1949 became a symbol for the peace movement. Picasso also used animals to represent moments of suffering and violence. In his prints, The Dream and Lie of Franco 1937, he critiques and mocks General Francisco Franco, dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1973, who led the fascist forces in the Spanish Civil War. These works include images of horses in extreme distress, something Picasso would famously use again in his anti-war masterpiece Guernica 1937, which can be seen today on display in Madrid.

Violence could also be exciting to Picasso, particularly in the form of bullfighting. It was a frequent theme in his work – a theatrical, hyper-masculine triumph of humans over death, represented in the primal form of the bull.

‘High’ and ‘Low’ Culture

It is impossible to say exactly what the figures in The Three Dancers are dancing. What is clear is that the dancers evoke both joy and deep longing. At the time of painting, Picasso was grieving the death of his friend, the painter Ramón Pichot. The painting is often read as an allegory of a tragic love triangle entangling friends and lovers of Picasso’s youth.

In Spanish, there are two words for dance: baile, meaning social or spontaneous dancing, and danza, which is formal and professional. Both types of movements appear in The Three Dancers. Picasso seamlessly moves between popular and formalised modern gestures, uniting high and low culture, perhaps in articulation of his own condition as a bohemian artist in Paris. In doing so he connects a personal tragedy to an archive of longing implicit in popular forms such as flamenco, which is often associated with marginalised and diasporic communities.

Theatre

Picasso had a close relationship with the performing arts. He designed dance sets and costumes and even wrote and directed his own play Desire Caught by the Tail 1941. Picasso contributed to many stage productions, notably working with the famous dance company Ballet Russes. In two of his stage designs shown here, he played with the idea of perspective and illusion. Pulcinella 1920 used a trick-of-the-eye effect, while Cuadro Flamenco 1921 flipped that idea inside out. This approach turns theatre into an illusion within an illusion, highlighting the idea of performance itself.

This game of illusions was especially important to Picasso. It is possible to think that this is why he found Pulcinella to be a character particularly in tune with his philosophy. Pulcinella is a traditional character from commedia dell’arte, a form of tragicomic theatre popular in Europe between the sixteenth and eighteenth century, known for obscene humour.

Acrobat

The acrobat’s bodily contortions are reminiscent of Picasso’s own evolution as a painter. Just as the acrobat experiments with the forms adopted by their body, Picasso experimented with the way in which he presented himself and represented reality, playing with our expectations of societal norms. He was fascinated with circus performers, harlequins, jesters and other nonconforming bodies. He often depicted his subjects as hyper-masculine, androgynous, hyper-sexual or animalistic, exploring the limits of what it means to be human.

The Unknown Masterpiece

Despite cultivating a myth of his genius, for Picasso, the masterpiece became an obsession and its achievement an impossibility. Picasso was notably inspired by Honoré de Balzac's 1831 story The Unknown Masterpiece and he went on to illustrate a 1931 edition. The story is about an old painter who was been working for years on an unseen portrait of a woman that is finally revealed as a confusing mass of colours, with no recognisable figures for his viewers, driving the painter to despair. We can see in Picasso’s painting Artist and His Model 1926 how strongly he identified with the artist’s creative struggle to capture the sitter.