A prominent feature of London’s art schools in this period has been cross-fertilisation among them. Significant faculty often taught in several institutions either sequentially or simultaneously, and art students frequently progressed between schools – necessarily so in the case of those institutions that only taught postgraduates. Institutional identities nevertheless persist; our contributors have created outline histories from c.1960 for those schools of particular interest to this publication. While these profiles are by no means comprehensive, the division of each institutional history into elements such as qualifications, building location and faculty means that significant details can be compared.

Camberwell

The life room at Camberwell

Published in John Russell, Bryan Robertson, Lord Snowdon, Private View: The Lively World of British Art, 1965

Photograph by Snowdon/Trunk Archive

DEPARTMENTS AND QUALIFICATIONS

In the early 1960s Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts was organised into three departments: Painting and Sculpture; Design and Crafts; and Printing and Bookbinding. An Art History Department was formally established in 1961 and Foundation Studies were introduced in 1962. By 1968 the School was organised into eight departments: Painting; Sculpture; Graphic Design; Ceramics and Metalwork; Textiles; Foundation Studies; Art History; and Printing. Paper conservation courses began in 1970, and in 1974 the Council for National Academic Awards approved BA degrees in painting; sculpture; graphic design; printed and woven textiles; and ceramics (with silversmithing and metalwork introduced in 1976). Vocational courses in printing and typographical design were phased out at the beginning of the 1980s, and in 1983 the textiles degree course was lost.

In 1986 Camberwell became a constituent college of the London Institute. In 1989 it was renamed Camberwell College of Arts, and courses were organised into two schools: Applied and Graphic Arts; and Art History and Conservation. Between 1990 and 1993 five new courses were begun in line with the London Institute’s Academic Development Plan: BA Conservation; MA Conservation; a part-time BA in graphic design; BA Joint Honours in art and design; and an MA in printmaking. In 1993 the London Institute was granted the right to award degrees in its own name. In 1996 a new international MA Book Arts course was launched, built around the activities of the Camberwell Press.

In 1998 the college launched a new framework for its BA courses, offering students the opportunity to focus on a specialist discipline supplemented by chosen elective subjects. Art History closed in 2000 and courses in personal and professional development (focusing on skills such as teamwork, client liaison, self-promotion) were launched the same year. From 2011 Camberwell ran the only Foundation course within the Camberwell Chelsea Wimbledon (CCW) triumvirate.

BUILDINGS AND GEOGRAPHY

From its opening at the end of the nineteenth century Camberwell adjoined the South London Art Gallery. A new sculpture building was opened in 1953, providing workshops for modelling in clay, bronze casting, plaster casting, stone, and woodcarving. Between 1966 and 1971 additional accommodation was opened in Meeting House Lane (principally for painting) and Lyndhurst Grove (for textiles, ceramics, graphic design and Foundation studies), and a purpose-built sculpture annex was completed in 1969. In 1971 a new extension of 50,000 square feet was begun on the existing school’s site; it opened in 1974 and provided a further forty-two studio workshops and classrooms, new assembly and lecture halls, library and common rooms. In 1976 the former premises of Wilson’s Grammar School was taken over by the school.

STUDENT BODY AND PROFILE

Robert Medley in Drawn from the Life (1983) recalled Camberwell as ‘a typical and by no means especially prestigious example’ of an art school, despite its Coldstream legacy.1 It was defined by its south London location and its social ambitions, evidenced – for example – by the North Peckham Estate murals painted by textiles students in the mid-1970s or by the free ‘live art’ classes for the unemployed launched in 1984. In the inaugural publication from the Camberwell Press Eileen Hogan noted in 1984 that ‘while the Camberwell Press will form an important part of the practical and theoretical work carried out at the School, one of its more valuable purposes will be to share some of the concerns of the School with the world outside. The measure of any educational establishment may, in part, be counted by its contribution to the well-being of the community of which it forms a part’.2

While emphasising the advantages of being part of the much larger London Institute, the prospectus of 2000 noted Camberwell was renowned for a friendly and supportive atmosphere amongst staff and students. The sorts of collaborative and community-minded ventures outlined above might now be viewed as early points of reference for community-based projects such as Peckham Space, opened in 2010. As the sole centre for Foundation training in Camberwell Chelsea Wimbledon (CCW), Camberwell currently takes around 750 Foundation students each year.

SELECTED FACULTY

Michael Podro was Head of History of Art from 1964 to 1967, having joined in 1961. In 1966 staff included Frank Auerbach, Garth Evans, Peter Hobbs, Frank Martin, Robert Medley, Patrick Proctor, and Euan Uglow. T.J. Clark taught art history (1970–4) as did the artist Mary Kelly (1975–85) and Alex Potts (1981–9). Tony Carter was Principal Lecturer and Course Leader in sculpture (1986–9). Paul de Monchaux fulfilled various roles including Principal Lecturer in sculpture, Head of Painting and Head of Fine Art. Eileen Hogan set up and directed the Camberwell Press from 1984 to 1996 and was Dean from 1989 to 1997. During the 1988–9 academic year, cuts to fine art courses at Camberwell were planned by the London Institute. Wendy Smith, Head of the Department of Fine Art, and Tony Carter resigned in protest, returning when the cuts were reduced. Susan Johanknecht joined in 2001, heading the MA in book arts.

Central School

Anton Ehrenzweig teaching in the textiles studio, Central School of Arts and Crafts, London, c.1951

Photographer unknown

Tate Archive TGA 201010

DEPARTMENTS AND QUALIFICATIONS

The Central School of Arts and Crafts was renamed the Central School of Art and Design in May 1966 and was among the first UK colleges to be accredited across all of the DipAD’s four main areas (fine art [painting], graphic design, 3D design and fashion textiles). In the 1960s it gradually diminished its emphasis on crafts, establishing history and liberal studies, a Pre-Dip/Foundation Department, and the library. In 1967 the NCDAD designated a joint centre for postgraduate studies composed of Chelsea School of Art for Fine Art and Central for Design. This mandate was a harbinger of the programme and school mergers of subsequent decades. In 1984 the ILEA spearheaded the first merger, in response to financial pressure and claims of London’s over-provision for art education: St Martin’s and Central merged their fine art and graphic design courses. The new BA Fine Art was divided into four subject areas: painting, sculpture, printmaking, and film. Central and St Martin’s then combined the Department of Fine Art into a ‘School of Art’. By 1989 the schools merged to form the Central Saint Martin’s College of Art and Design’ (CSM). Under its first Rector John McKenzie, art schools were renamed ‘Colleges’, and the term ‘School’ denoted the combination of former departments. The post of ‘Principal’ became instead the ‘Head of College’, and Deans were created to head up the new-style schools. The Byam Shaw School of Art (founded in 1910) was merged into Central Saint Martin’s in 2003, which was itself absorbed by the University of the Arts in 2004.

BUILDINGS AND GEOGRAPHY

The Central School occupied its historic Arts and Crafts custom-built premises on Southampton Row in central London from 1908 to 2012. The architecture of the school influenced the level of interdisciplinary interaction, which seemingly conspired to create an empire of autonomous departmental kingdoms. From the early 1960s the Painting Department was located on the top floor; Sculpture in the basement; Jewellery was located on the second floor; and Industrial Design on the third floor. In 1962 Central expanded into new premises in Red Lion Square near the British Museum and the Jeanetta Cochrane Theatre opened soon after. In 2011 Central Saint Martin’s relocated to a converted mid-nineteenth-century granary building in King’s Cross, bringing together almost all of the courses offered by the College under one roof.

STUDENT BODY AND PROFILE

The first intake of DipAD students arrived in 1962. The students were socially diverse and to some extent international. Small class sizes were a feature of the early 1960s, with a staff-student ratio of 1:10, although overwhelming numbers of applications for the new DipAD soon changed this. Even before the rising significance of DipAD degree shows, considerable importance was placed on the annual student exhibition at Central. There were clear guidelines regarding the sale of student work: all work sold should contribute a percentage to the School Fund, and students should be admonished for working on commissions – a means of securing cheaper work that could therefore undermine professional rates of pay.

During the 1960s Central began to manage more deliberately its incoming student demographic. Board notes reveal a growing concern of Principal Michael Pattrick and other staff members about the desirability of continuing with students on day-release from prison, for instance. Meanwhile, the increased demand for new media led to discussions about the provisions for teaching photography. A blend of photography and film enjoyed flourishing interest from a growing segment of incoming students. By the mid-1970s the Fine Art Department had approximately ninety students working for the DipAD degree, with an annual intake of twenty painting and ten sculpture students. The merger with St Martin’s in the 1980s was difficult for many of the staff at Central, given the differences of character and departmental structure of the two institutions. Jane Rapley, former Dean of Central Saint Martins, recalls: ‘Central was many small departments and they were quite British Museumy and Bloomsbury in nature … its primacy was in the 1950s, and it was a bit more measured and quieter.’3

SELECTED FACULTY

Central’s heyday for pedagogic innovation was in the 1950s under its then Principal William Johnstone, who retired in 1960, to be succeeded by Michael Pattrick. Maurice Kestleman led the Painting Department from 1951 to 1971 and during this period it had a relatively traditional profile. Staff such as Cecil Collins (1951–75) contrasted with a more progressive line-up of visiting tutors. The Fine Art Department’s staff comprised: the Head; a Senior Lecturer in painting; a Senior Lecturer in sculpture; and around fifty part-time visiting staff. Brian Wall was Head of Sculpture from 1962 to 1972. Shelley Fausset ran the Foundation Department from 1963 to 1982. The appointment of Hubert Dalwood as Head of Sculpture (1974–6) coincided with Robert Clatworthy’s ascension as Head of Fine Art, which precipitated debate around studio-based practice in the face of increasingly conceptually-focused curricula. After the first merger, Ian Simpson (then Principal of St Martin’s) became Head of Fine Art, supported by John Edwards in painting, Steve Furlonger in sculpture, David Glück in printmaking, and Malcolm Le Grice in film. By 1986 the Inner London Education Authority, headed by William Stubbs, established the London Institute. Its Rector, John McKenzie, emphasised that he wanted Central and St Martin’s to preserve their distinct identities despite sharing resources and students. With its hierarchy clarified – a Rector overseeing Heads of Colleges overseeing Deans – Central Saint Martin’s saw David Sherlock assume the first Head of College role (1988–91); he was succeeded by Margaret Buck, and she by Jane Rapley. Rod Bugg was Dean of Art from 1993 to 1997, Chris Wainwright from 1997 to 2007 and Mark Dunhill followed on after him.

Chelsea

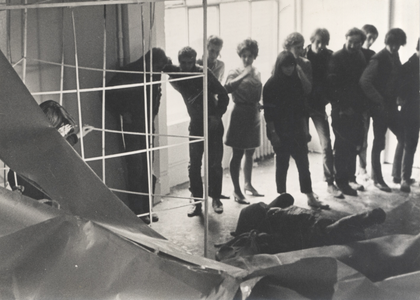

Lawrence Gowing in Chelsea School of Art, 1965

© Chelsea College of Arts, University of the Arts London

DEPARTMENTS AND QUALIFICATIONS

A new Chelsea School of Art, directly managed by the London County Council, was formed in 1964 when the original art school split from Chelsea College of Science and Technology and amalgamated with the Polytechnic School of Art, Great Titchfield Street (previously the West London School of Art and part of the Regent Street Polytechnic). In 1975 Hammersmith School of Building and Arts and Crafts (established in 1881) merged with Chelsea. In January 1986 Chelsea School of Art became a constituent college of the London Institute, formed by the Inner London Education Authority, becoming Chelsea College of Art and Design in 1989. Chelsea College of Arts is now part of a ‘Camberwell Chelsea Wimbledon’ triumvirate, together with Camberwell College of Arts and Wimbledon College of Art, within the University of the Arts London.

Chelsea had been accredited for diplomas in painting and graphic design in 1963 and sculpture in 1964. In 1965 it was approved to offer a postgraduate diploma in fine art (which became the MA in 1974). From 1958 Lawrence Gowing integrated history and theory with practice, employing artists rather than art historians to teach art history and theory, and introducing seminar ‘options’, which included workshops on experimental music, poetry, artists’ books, psychoanalysis, philosophy and anthropology. New courses since 1989 include the conversion of three HNDs – mural design, textile design, and interior/product design – into a BA Honours in design, and MAs in the history and theory of modern art, and the theory and practice of public art (the latter revalidated in 1998 as the multi-disciplinary MA in design for the environment). The design portfolio expanded, and in place of separate pathways, the BA Honours courses in graphic design for communication, interior and spatial design and textile design became individual degrees. MAs in critical writing and curatorial practice and graphic design communication have also become part of the College’s portfolio.

BUILDINGS AND GEOGRAPHY

Chelsea was historically London’s bohemian quarter. In 1965 Chelsea’s purpose-built Manresa Road site opened. By 1975 Chelsea had acquired the Bagley’s Lane site – a hastily converted primary school campus. This was used as an annex to Manresa Road. Following amalgamation with Hammersmith School of Building and Arts and Crafts, Chelsea gained Lime Grove, a late nineteenth-century Arts and Crafts building, which included purpose-built artists’ studios and workshops. Lime Grove became the hub for design courses including mural painting, glass mosaic and ceramic, textile design and interior/product design. In 1981 Chelsea acquired additional premises at Hugon Road, a converted Victorian primary school where graphic design activity was based. Chelsea relocated to a single site at Millbank, opposite Tate Britain, in January 2005.

STUDENT BODY AND PROFILE

Initially, most students were native Londoners; this has now changed with many students coming from abroad. In 1965 the London County Council Education Officer boasted that Chelsea had forty-eight students enrolled for the fine art diploma – ‘the largest number of any school of its kind in the country’ – and that the total number of full-time students enrolled at this time was 223.4 The first cohort of PGDip students staged their end of year show in 1967. Chelsea graduate Jonathan Harvey (1971–2) co-founded Acme Studios in 1972 to provide affordable studio space, residencies and awards. Acme now supports a Studio Award for final year BA Fine Art students from Chelsea. When the DipAD qualification was first replaced with the BA (for the cohort graduating in 1975), students occupied the building overnight and staged a rooftop protest. Painting students benefited from a unique ‘studio system’. Prospectuses dating from the 1980s describe ‘small close-knit groups of students and artists brought together by similar interests and by the need for similar resources’. A similar system operated in the sculpture workshops where students of all stages, from Foundation to undergraduate and postgraduate, mixed. By 2011 the college comprised 1,400 degree students.

SELECTED FACULTY

Lawrence Gowing took over as Head in 1958 and was succeeded by Fred Brill in 1965 (who was Head until 1979). John Hoyland led the postgraduate diploma course from 1965. Ian Stephenson taught basic design and painting from 1959 to 1966, and later ran the postgraduate programme, including the MA Fine Art from its inauguration in 1974 (Stephenson retired in 1989). Other teachers at the time of the inauguration of the new school included Michael Andrews, Frank Auerbach, Patrick Caulfield, Prunella Clough, Anthony Hill, Leon Kossoff, Norbert Lynton, Myles Murphy, Norman Norris and Matt Rugg. Stephen Bury was Librarian from 1979 to 2000. John Barnicoat was Principal from 1980 to 1989. William Callaway became Head of College in 1989, the same year Colin Cina became the first Dean of Art and Bridget Jackson the first Dean of Design. Euan Uglow taught at Chelsea during this time. Jackson followed Callaway as Principal from 1992 to 1997 and was succeeded by Colin Cina from 1997 to 2003. Roger Wilson led the College from 2003 to 2006. Chris Wainwright became Head of Colleges for Chelsea, Camberwell and Wimbledon in 2007.

Goldsmiths

DEPARTMENTS AND QUALIFICATIONS

In 1964 the DipAD in textiles at Goldsmiths, with embroidery as the main subject and printed textiles and weaving as subsidiary subjects, was the first to be ratified in Britain. In 1969–70 the Art Teachers’ Certificate course was the most sought after in the country and 331 students applied for sixty-three places. From 1968 Jon Thompson sought to unify the Painting and Sculpture Departments, making for ease of mobility for students between the two.

In the second half of the 1970s the School of Art and Design expanded undergraduate courses and worked to establish postgraduate courses, with higher degrees and in-service courses as well as research degrees, MPhils and PhDs. In 1978 the first students embarked on a new MA in fine art, and forty students registered for the new communication studies degree in the Department of Visual Communications. An approved BA in art/ history of art began in 1981, and the CNNA soon after approved single honours degrees in fine art and embroidery textiles. In 1983 the Art Teacher’s Certificate course moved to the Faculty of Education. In 1985 the University began a new BA Art (Studio Practice) and History of Art degree to replace the Institute of Education degree. 1987 saw the creation of a new Faculty of Arts, including Humanities Departments as well as Creative and Performing Arts. Goldsmiths received its Royal Charter in 1990.

A re-branding exercise in 2007 dropped the word ‘College’ from the institution’s name, and new degrees were introduced, such as a MFA in computational studio arts.

BUILDINGS AND GEOGRAPHY

Various buildings on the New Cross site have at different times housed the Department’s staff and students. Negotiations for the lease of additional accommodation at Surrey Docks were completed before the 1972–3 session began. Working parties of staff and students set about converting the space. Fine art, history of art and textiles all moved to the newly acquired Millard Building (St Gabriel’s site) in Camberwell in 1978 after expiry of the Surrey Docks lease. In 1988 the move from the Camberwell site back to the main New Cross site became possible when space was liberated by the building of the new college library. January 2005 saw the unveiling of the new Ben Pimlott Building, designed by architects Alsop & Partners to house the Department of Art. Almost immediately, however, growing student numbers meant the spaces provided were inadequate.

STUDENT BODY AND PROFILE

Goldsmiths began primarily as an institution specialising in education and the training of primary and secondary school teachers. Those early years informed a continuing concern with education and pedagogical practices in general which seems to have acted as a point of departure for art education. In 1961 211 full-time students were recruited to the School of Art. Annual Reports note that by 1972 student numbers had reached around 300. Critic Richard Shone in Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection (London 1997) suggests that, at Goldsmiths, ‘the impact of the teaching in the 1980s produced a remarkable generation. Their example and several important early shows that they themselves devised became a source of energy that affected a mass of students in other schools and paved the way for the [...] seemingly unstoppable exposure of new British art’.5 At the beginning of 1988 Angus Fairhurst, a second-year student at Goldsmiths, organised a show in the Bloomsbury Gallery of the Institute of Education. Damien Hirst was already planning for an ambitious three-part show called Freeze later in the year to be held in an empty London Port Authority warehouse loaned by the London Docklands Development Corporation. On the occasion of Goldsmiths’s centenary in 1991, A.E. Firth noted that in the British Art Show of 1990 (which featured forty artists under the age of thirty-five, selected from 2,800 nationally), thirteen of those exhibited had studied at Goldsmiths.

SELECTED FACULTY

In 1963–4 Seonaid Robertson, a teacher on the Art Teacher Certificate course and a follower of the critic and author Herbert Read, delivered a lecture in Tokyo titled ‘Art Education in the Computer Age’. From 1964 to 1966 Anton Ehrenzweig, along with Tony Collinge, ran a radical new Art Teachers Certificate course. In 1968 Jon Thompson joined as lecturer in charge of the first year DipAD in painting and sculpture, becoming Head of Fine Art in 1970 (the year of Andrew Forge’s departure). Constance Howard retired as Head of Textiles in 1975, to be succeeded by Audrey Walker, who in 1988 was succeeded by Christine Risley. In 1994 Rosalind Floyd and Shirley Craven retired and Janis Jeffries became Head of the Textiles Study Area. In the 1970s Maurice Agis taught sculpture. Philip Rawson became Dean of the Faculty of Arts in 1980. In 1983 Harry Thubron retired after ten years at Goldsmiths. In 1987 Nick de Ville became Head of Department. Michael Craig-Martin taught between 1974 and 1988 and returned from 1994 to 2000. Richard Noble, a philosopher by training, joined Goldsmiths initially as a part-time Lecturer in the Department of Visual Art in 2003, before becoming Head of Department.

St Martin’s

Frank Martin (middle-right) teaching in the Sculpture Department at St Martin’s School of Art, mid-1950s

Tate Archive, Frank Martin collection

© Frank Martin Estate

DEPARTMENTS AND QUALIFICATIONS

Fine art at St Martin’s initially comprised painting and sculpture, of which painting was the more popular. In 1964 the two departments temporarily – and notionally – merged in order to gain DipAD accreditation. Sculpture’s ‘Advanced Course’ enabled talented students to work in a quasi-graduate studio environment. By c.1965 there was a Foundation Department in addition to a smaller History of Art and Complementary Studies Department. In the early 1970s the ‘A’ course taught conceptually-inclined sculpture undergraduates, and the ‘B’ course catered for those interested in ‘object’ sculpture. The Painting Department refreshed its understanding of the discipline, positioning painting as the core of a wider range of activities that included photography, film, print-making in various media, as well as traditional features like the life room. A free-standing Film and Video Unit was officially established in 1976. The bias toward painting remained into the 1980s: in 1980–1, of fine art students (in BA and Advanced courses) 119 were painters and 58 were sculptors, with another 103 Foundation students. Sculpture foundered and was closed by the Council for National Academic Awards in 1983. In 1984 the Inner London Education Authority merged fine art and graphic design courses at Central and St Martin’s.

BUILDINGS AND GEOGRAPHY

St Martin’s School of Art was the most centrally located of the London art schools; it occupied its Charing Cross Road building from 1939 until 2011, and its location was significant. Close proximity to Soho meant that students were immersed in popular culture, fashion and music, as well as close to galleries and museums. Its premises always struggled to accommodate student numbers, and intramural arrangements were unconventional. The Sculpture Department occupied impractical upper floor rooms as well as basement and courtyard spaces that accommodated, respectively, the welding workshop and an impromptu display and storage area. In an effort to accommodate growing numbers of students, St Martin’s leased space on Archer Street, Greek Street and 145 Charing Cross Road. In 1979 they acquired a building at Long Acre (used by Graphic Design, the Film and Video Unit and some of the Painting Department) until a new site in Red Lion Square near the British Museum was acquired in 1998. Moving premises was a long-standing ambition of the school, realised eventually in 2011 with its move to the King’s Cross location.

STUDENT BODY AND PROFILE

St Martin’s did not enjoy an established, illustrious history, but rather invented a reputation from the 1960s, quickly becoming one of the most renowned fine art and design schools in the UK. In 1961–2 there were 166 painting students compared with forty-seven sculpture students. Its success was indicated by graduates establishing names as practitioners, and by high numbers going on to graduate programmes at the RCA. St Martin’s was a very large school: in 1961 there were over 500 full-time students and among this number were many international students. By the start of the 1978 academic year there were 650 full-time students. Former Dean of Central Saint Martins, Jane Rapley, recalls that ‘St Martin’s was Soho … It was about three tower blocks [Art, Fashion and Graphic Design] who fought each other, and they were street fighters … St Martin’s primacy was very 1960s, 1970s … very out there and up front’.6 Of the eventual merger between Central and St Martin’s in the 1980s, she says: ‘It is interesting but it is the St Martin’s cultural heritage that has dominated Central Saint Martin’s despite the fact that Central was in a better shape than St Martin’s was, in my view, when we merged.’7 John McKensie, the first Rector of the London Institute, brought a business sense to the merger, broadening the outreach for students, drawing heavily from an international pool of students. Still, McKensie wanted both schools to preserve their identities, even as they worked together with shared resources and students. However, from 2011, the sharing of the King’s Cross location erased what remained of a discrete legacy of a uniquely St Martin’s – as opposed to Central Saint-Martin’s – culture.

SELECTED FACULTY

Edward Morss was Principal from 1946 to 1972. Frederick Gore (Vice Principal from 1961 to 1979) headed painting, Frank Martin sculpture, and Ken Bale the Foundation course. Martin recruited progressive sculptors as tutors in his department. Heterogeneous practices enriched the Department, which included both object makers (Anthony Caro and New Generation sculptors) and conceptualists (Barry Flanagan, Gilbert & George). Erosion of media boundaries was evidenced by Malcolm Le Grice’s 1967 establishment of an Experimental Film Unit. Ian Simpson was Principal from 1972 to 1988. At the beginning of the 1970s the Painting Department employed one full-time staff member supported by twenty-five visiting lecturers (Sculpture employed two full-time lecturers with twenty-three visiting tutors, while Foundation Studies employed three full-time members of staff and forty visiting lecturers). Tim Scott took over as Head of Sculpture in 1981, following Frank Martin’s retirement.

Royal College of Art

David Hockney and Derek Boshier at the Royal College of Art, in front of Hockney’s We Two Boys Together Clinging 1961, photographed 1962

Photo © Geoffrey Reeve

DEPARTMENTS AND QUALIFICATIONS

Since 1967, when the college was granted a Royal Charter endowing it with university status and the power to grant its own degrees, the Royal College of Art has been the only wholly postgraduate university institution of art and design in the UK. If the 1960 Coldstream Report stated that ‘students should not specialise too narrowly’, emphasising that a unified fine art area rather than courses focusing intensely on one subject were unsuitable for the diploma, such a directive did not apply to the RCA.8

As an exclusively postgraduate college, the RCA continued to run mostly independent schools of painting, sculpture, printmaking, graphic design, industrial design, textile and fashion. Initially, the master qualification was denied to fashion students, a decision which caused an internal uproar. In the late 1950s and 1960s, courses in industrial design and vehicle design were introduced. In the 1970s two short-lived but influential courses were established: environmental media (under Peter Kardia) and the Film and TV Department. In 1971 Bruce Archer was invited to create the Department of Design Research, which he ran until it was closed, not without controversy, in 1984. In the 1980s the Department of Interior Design was split into two courses: architecture and interior design. In the 1980s and 1990s the Product Design Department grew significantly while Animation became a Department in its own right and a Humanities Department was established. In 1989 the Fashion and Textile Departments were amalgamated. The department of Conservation was founded in 1987 in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, and a course in Visual Arts Administration (then Curating Contemporary Art) was founded in 1992 in association with the Arts Council of Great Britain (Arts Council England from 1994). In 2014 the RCA offered twenty-four distinctive postgraduate programmes across art and design.

BUILDINGS AND GEOGRAPHY

In the 1950s Robin Darwin engaged in what he defined as a ‘difficult battle’ to convince the Ministry of Education of the need to found a large, centralised building.9 Referring to the erection of a purpose-built gallery within the new college (1962), Darwin explained his ambitions in relation to the new large hall of the new building: ‘This Hall has been designed primarily as an exhibition centre which we hope may be used for important exhibitions organised by the Arts Council and others.’10 In 1962 all design and applied art courses moved to the new Darwin Building in Kensington Gore, while painting remained housed in Victorian studios on Exhibition Road, adjacent to the Victoria and Albert Museum, until 1992, when the college opened the new Stevens Building in Kensington Gore. In 2008, after many years of the sculpture studios being housed in an agglomeration of temporary structures, the Sculpture Department found a permanent home in a refurbished building at Howie Street, Battersea. By 2012, with the completion of the Dyson Building at Battersea, the School of Fine Art, including the Painting, Photography and Printmaking Departments, alongside the Sculpture Department, were brought together in one location.

STUDENT BODY AND PROFILE

Narrating the history of the RCA in the post-war period in Exhibition Road (1988), former Rector Christopher Frayling asserted that: ‘Successive Government Ministries and Boards, under whose aegis the College came, continually emphasised what they saw as an unquestionable need for the College to train designers for industry, not “fine artists” who might compete with the Royal Academy Schools.’11 Yet, the RCA managed to remain an art school as well as a design school. The RCA magazine ARK (1950–78) bore testimony to the collaboration and cross-pollination of design students and painters, especially with the development of the pop movement. The 1950s and 1960s saw the RCA at the centre of the explosion of pop art culture (students included Peter Blake, Joe Tilson, Derek Boshier, David Hockney, Allen Jones, R.B. Kitaj and Patrick Caulfield in the School of Painting and Pauline Boty in the School of Stained Glass). In 1968, when it became a purely postgraduate institution, the RCA numbered some 550 students. Most students up to the 1970s were enrolled in the Painting Department. In the early 2010s approximately 75% of the students and staff were design oriented.

SELECTED FACULTY

Robin Darwin was the College’s Principal from 1948 to 1967 and Rector between 1967 and 1971. He was succeeded by Jocelyn Stevens (1984–92), Anthony Jones (1992–6), Christopher Frayling (1996–2009) and Paul Thompson (2009– present). Misha Black was the first Professor of Industrial Design (1959–75). Professors of Printmaking have included Edwin laDell (1955–70), Alistair Grant (1970–90) and Tim Mara (1990–7); Professors of Painting encompass Carel Weight (1957–72), Peter de Francia (1972–86) and Paul Huxley (1986–98); and Professors of Sculpture include Bernard Meadows (1960–80), Phillip King (1980–90) and Glynn Williams (1990–2009). Among notable part-time and visiting teachers of painting were Ruskin Spear (1948–75), Sandra Blow (1961–75) and Peter Blake, who also taught in the Printmaking Department (1964–76).

Slade School of Fine Art

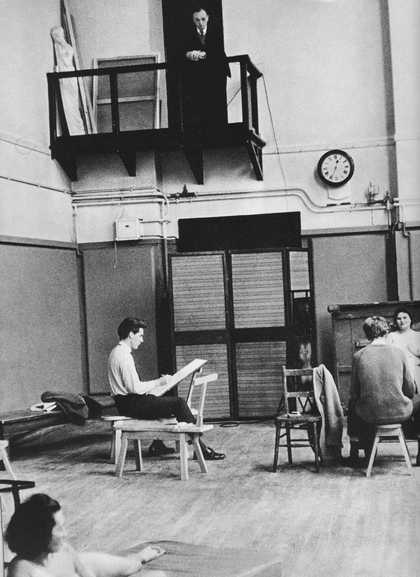

William Coldstream observing the life room from the balcony of his office at the Slade

Published in John Russell, Bryan Robertson, Lord Snowdon, Private View: The Lively World of British Art, 1965

Photograph by Snowdon/Trunk Archive

DEPARTMENTS AND QUALIFICATIONS

At the Slade, the areas of study since 1960 were for the most part divided into painting, sculpture, printmaking, media and theatre design. Today these areas are painting, sculpture and fine art media. The UK’s first film course was introduced in 1960 (seemingly at postgraduate level initially) and was led by Thorold Dickinson who subsequently became a professor, before retirement in 1971. Film was joined in 1972 by a computer department, the Department of Experiment, whose developments reflected the efforts of Malcolm Hughes and Chris Briscoe. A postgraduate diploma was formally introduced in the mid-1960s. In 1970 art history and anatomy turned from compulsory into optional subjects for the University of London diploma in fine art. Section directorships were phased out in favour of a structure of senior lecturers supported by visiting tutors. Bernard Cohen introduced an Art History chair, MA, MFA and Doctoral programmes under his directorship. The Slade Centre for Electronic Media in Fine Art (SCEMFA) opened in 1995.

BUILDINGS AND GEOGRAPHY

The Slade is at the heart of University College London on the western edge of Bloomsbury, and students have been encouraged to engage with other university departments such as Engineering from the 1950s onwards. The artist Richard Hamilton’s exhibition Growth & Form, held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, in 1951, shared its title with the series of lectures given the biologist John Z. Young. Students also attended lectures in the Anatomy and Psychology Departments. In 1963 the Antique Room was dismantled. Postgraduates moved to the Pearson Building in 1975; in 1991 postgraduate painting moved around the corner to the former Courtauld Gallery on Woburn Square.

Extensive renovations were carried out in the mid-1990s, when mezzanines controversially divided the painting studios, and the sculpture studios below ground were modernised. Structural alterations are an illuminating sign of departmental shifts: for instance, faculty meeting minutes of 8 November 1976 record the proposal to expand photography facilities by cutting into what were increasingly under-used models’ bathrooms and shower areas.

STUDENT BODY AND PROFILE

James Hyman in The Battle for Realism (London and New Haven 2001) characterised the early Slade as a patrician school, citing Frank Auerbach’s view that it had ‘many more upper-middle class students’ than the RCA, and Paula Rego, who claimed ‘The Royal College seemed plebeian compared to the Slade’.12 There was a distinctive administrative engagement with students: a staff/student committee began in 1968, and in 1973 there was a student demonstration complaining about the Slade’s poor library resources. Stephen Chaplin’s Slade Archive Reader (unpublished, 1998) identified a change around 1964, when, ‘Teaching changed from the easel-visit current from Poynter’s time, to the group tutorial, or “crit” of the 1970s, where groups of students would discuss one of their number’s work with staff’.13 By the 1970s the Slade’s cerebral character led to debates about art’s role in society featuring prominently in the school.

The student population has been reasonably stable over the decades, with around 200, evenly divided between undergraduate and postgraduate levels. The current population is approximately 140 undergraduate students and 120 postgraduates, the slight growth reflecting increased availability of space after the 1990s renovations. A notable change has been the cessation of part-time study; in the 1950s and 1960s part-time students were a substantial minority of the student population, but in the 1980s they were discontinued.

SELECTED FACULTY

William Coldstream significantly increased the number of visiting and assistant tutors during his period as Principal from 1949 to 1975. In the early 1960s Claude Rogers and Andrew Forge both left. Alfred H. Gerrard was Professor of Sculpture from 1949 to 1968. Ian Tregarthen Jenkin was a support to Coldstream, and also retired in 1975. Lawrence Gowing took over as Slade Professor until 1985, to be succeeded briefly by Patrick George (who had been there from 1949, and notably ran the F studio where undergraduate students worked alongside postgraduates). Bernard Cohen was Slade Professor from 1988; then John Aiken took over, to be succeeded by Susan Collins. From 1959 Leopold Ettlinger was the Durning Lawrence chair of Art History and oversaw the department’s migration into a separate faculty in University College London in 1964. Euan Uglow, Norman Norris, Tess Jaray and David Hepher were among the more prominent tutors of the Painting Department.