Tate Research Workshop

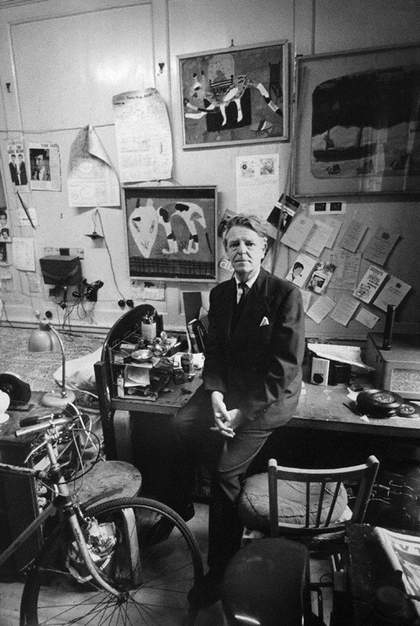

Lord Snowdon

Adrian Stokes (Church Row, Hampstead) 30 October 1963

© SNOWDON / Camera Press

Read a description of this portrait

24 May 2013

Convenor: Paul Tucker

Adrian Stokes was a writer whose work eludes classification. The generic label ‘art writer’ perhaps best fits his case. Though raising more questions than it answers, it nonetheless identifies Stokes’s principal, abiding interest and reflects too his studied indeterminacy of approach. From the late 1920s to the 1960s his writings focused on visual art (including classical ballet), yet his aims and methods were never simply or straightforwardly critical, historiographical or theoretical. He took issue with the abstract aesthetic emotivism of formalists such as Clive Bell and Roger Fry, affirming rather the profound ‘co-ordination of art and life’ epitomised by the interfusion of form and content in the artwork. From the late 1940s his engagement with, and explication of, the experience of visual art was explicitly mediated by psychoanalytical theory, particularly that of Melanie Klein, with whom he had undergone analysis in the 1930s. Yet his friend and interpreter, the philosopher Richard Wollheim, claimed Stokes ‘didn’t want to be a theoretical writer about art in the light of psychoanalysis’.1 This accords with what Wollheim elsewhere reports of his characteristic mistrust of philosophical abstraction, but also with Stokes’s own repeated complaint that psychoanalytical theorists of art tended to ignore the specificity of artistic form.

‘I will to be different’, he had written in an early notebook.2 Throughout his life he was impelled – and by his private income, determination and talents enabled – to reconstruct his identity. By turn he schooled himself to become a historian of fifteenth-century Italian sculpture and architecture, a critic of contemporary sculpture and of classical ballet, a painter, a market gardener (in St Ives during the war), a psychoanalytical theorist, a museum official (he was a Tate trustee in the 1960s) and a poet, as well as a husband and father. He did so largely, perhaps always, in subordination to an image of art – ‘an entity that is always there … glowing like a still and radiant flower’ – which, he wrote in 1968, had haunted him since his first visit to Italy over forty years before,3 and which, while it remained constant, acquired new meaning and depth as his experience changed.

Such resolute and multiform ‘identity-in-difference’ makes Stokes a writer of considerable richness and complexity and of edifying status, whose aims and achievements require attentive reconstruction and appraisal. This task is all the more necessary and difficult in that a misleading, or at any rate partial, view of his work is given by the posthumous three-volume Critical Writings, edited in 1978 by Lawrence Gowing (but like most of his books now out-of-print). This had the undeniable merit of reprinting a large number of his published writings in non-anthologised form. At the same time it mutilated the body of his work considered as an organic whole, cutting away his first two books (The Thread of Ariadne [1925] and Sunrise in the West [1926]), the essays published for T.S. Eliot in the Criterion (‘The Sculptor Agostino di Duccio’ [1929], ‘Painting, Giorgione and Barbaro’ [1930]), the two books on ballet (To-night the Ballet [1934] and Russian Ballets [1935]), a quantity of uncollected ballet criticism and theory, the psychoanalytical papers (a selection of which were published posthumously as A Game that Must be Lost [1973]), book reviews, lectures and occasional pieces. No attempt, moreover, was made to edit the writings included in the three volumes, or to elucidate the history of their composition by reference to the extensive collection of notebooks, drafts, proofs and correspondence carefully preserved by Stokes himself throughout his life, now in the Tate Archive.

The main aim of the workshop was thus to explore the ways in which uncollected and archival material might help reconstitute and aid understanding of the larger body of Stokes’s work, by illuminating the intricate and often protracted genesis of individual writings, of specific interests and of key theoretical and critical categories, by exposing to view his methods of composition and by clarifying his modes of interaction within successive cultural and intellectual environments.