Tate Research Workshop

13 December 2013

Convenor: Andrew Stephenson

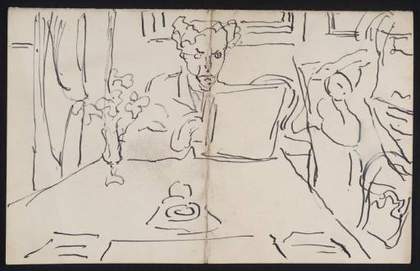

Sketch of Roger Fry by Vanessa Bell, in a letter to Clive Bell

© Henrietta Garnett. All rights reserved.

Tate TGA/8010/2/80/d

The first two decades of the Georgian period were distinguished by a series of significant shifts in the approach to art writing and in the perceived responsibilities of its writers, not least due to the proliferation of art historical research in the previous decades and the increasing specialisation of the functions of the art critic, the art historian and the connoisseur. On the one hand, there was modernism’s harsh repudiation of nineteenth-century art – think of Blast’s condemnation of ‘the years 1837–1900’ – while, on the other, there was the desire of Bloomsbury writers and critics to find an appropriately gender-relevant vocabulary with which to validate their own urgent artistic and aesthetic preoccupations. For others, the legacies of the Arts and Crafts movement, aestheticism and the use of German metaphysical aesthetic models still provided compelling intellectual tools for critical enquiry. That these years signalled for many art writers a radicalisation of what could be said about and claimed for modern art, its aesthetics and its ‘psychology’ may seem obvious. Yet for some art writers this was not the primary imperative.

Arguing for the need to re-examine these important transformations in art writing, this workshop focuses on the practices, theories and methodologies of art writing in Britain in the 1910s and 1920s, and will investigate some of the authoritative critical voices of the period, including Walter Sickert, Roger Fry and Clive Bell, who provided innovative ways of positioning themselves as (re)viewers of modern art as well as signalling their personal attitudes towards contemporary developments in the studio, the museum, the art market and the art gallery. As shifts in the global consumption of modern art shaped the international reach of its community of viewers and readers, so the increasing overlap between art, theatre, literature and the emerging visual technologies of photography and cinema demanded updated, diversified forms of critical writing (as Sickert’s and Virginia Woolf’s work demonstrates). For some commentators there was an acute sense of historical rupture from the pre-1900 decades and the 1910s, and before and after the First World War. While for other art writers there was a marked sense of continuity and of the ongoing relevance of tradition to changes in the contemporary art scene. The urgent challenge for art writers and critics in the 1910s and 1920s was, therefore, how to respond to, express and communicate the complexities of contemporary artistic developments in and across this rapidly changing cultural field in Britain.