John Hayls

Portrait of a Lady and a Boy, with Pan (1655–9)

Tate

Historical analysis of Hayls’s painting

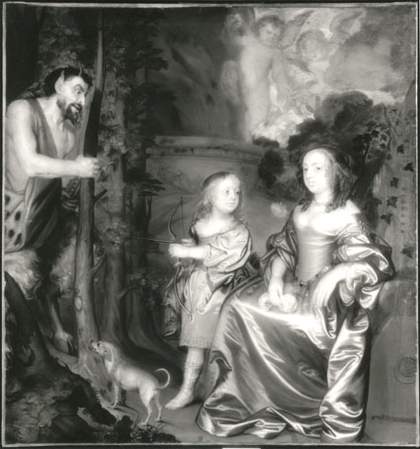

A Portrait of a Lady and a Boy with Pan 1655–9 by John Hayls was acquired by Tate in 1995. At that time it had the title A Portrait of Susannah Dalison and Her Son Thomas, which had been taken from a label on the back of the stretcher. Nothing was known about the sitters or about the history of the portrait.

A stencilled lot number on the stretcher was found to refer to a Christie’s sale of 1929, where the painting was described as: ‘LELY, Portrait of Mrs. Dobson, of West Peckham, Kent, and her son, Thomas Dobson, in a landscape with a Satyr and Cupids’. ‘Dobson’ seems to be a misreading of the word Dalison on the label but the mention of ‘Cupids’ was puzzling.

The painting next appeared as an illustrated advertisement in an edition of Connoisseur magazine in 1935, the composition appearing then exactly as it did in 1995. Clearly, the ‘Cupids’ described in 1929 had somehow disappeared in the intervening years.

Scientific analysis of Hayls’s painting

An infra-red photograph was taken to investigate what lay underneath the thick transparent dark blue paint of the sky. This photograph revealed not only two ‘Cupids’ or putti holding a wreath, but also a rose thrown into the lady’s lap and a theorbo (a long-necked lute) at the right of the composition.

John Hayls, A Portrait of a Lady and a Boy with Pan 1655–9

Oil on canvas; unconfirmed: 1730 x 1600 mm; painting

The painting as acquired in 1995, before treatment.

John Hayls, A Portrait of a Lady and a Boy with Pan 1655–9

A reflected infra-red photograph of the painting showing hidden features

The historical evidence showed that the painting must have been overpainted after the sale in 1929 and before the illustration in 1935. The blue pigment in the overpaint was analysed using EDX (energy-dispersive X-ray analysis) and polarised light microscopy, and found to be pthalocyanine or ‘monastral’ blue, a synthetic pigment which first came into use in the 1930s. The presence of this modern pigment confirmed that the overpainting was not original.

The painting during cleaning.

John Hayls, A Portrait of a Lady and a Boy with Pan 1655–9

The hidden putti were revealed

Revealing the overpainted cupids and musical instrument

Luckily, the overpaint was very resinous and it was easily soluble in the organic solvent mixture used to remove the discoloured varnish layer. The reason for the overpainting remains a mystery at present. The paint layers below proved to be in surprisingly good condition, so the overpaint was not applied to play its usual role of covering up a damaged surface. It is possible that the naked putti made the painting appear too risqué to sell, although this theory could not be applied to the theorbo. Perhaps it was simply the individual taste of an owner that prompted the alterations.

John Hayls, A Portrait of a Lady and a Boy with Pan 1655–9

The musical instrument was uncovered

Once the top layer of overpaint was removed, it became obvious that the bright blue brushy paint layer now on the surface was also not the original sky painted by Hayls. Inside areas of damage and around the margins of the putti, glimpses of the original discoloured paint of the sky can be seen.

John Hayls

A Portrait of a Lady and a Boy with Pan 1655–9

Detail of the putti after varnish removal, showing areas where the original grey-green sky is uncovered

Difficulties recovering the original colour of the sky

Hayls used smalt to paint the sky, a blue pigment that frequently discolours, explaining the current grey-brown appearance of the original paint. The bright blue overpaint, which contains the pigment indigo, was probably applied on top at quite an early date to disguise the fading of the smalt and has retained its bright blue colour.

Unfortunately the overpaint cannot be removed safely from the original paint without risking damage, so it must stay in place. This leaves an aesthetic problem as the jarring blue overpaint is crudely applied, its strong colour makes the sky area appear to come forward spatially and the use of indigo is inconsistent with the ultramarine, azurite and smalt found elsewhere in the painting.

The decision to paint in an ‘original’ sky colour

The current stage of the restoration of the painting is the careful and reversible inpainting of the overpaint to match the colour of the original sky more closely.

John Hayls A Portrait of a Lady and a Boy with Pan 1655–9

Detail of the right putto's wing, showing inpainting of the blue overpaint in progress

John Hayls

A Portrait of a Lady and a Boy with Pan 1655-9

The same detail, highlighting areas where the inpainting has been applied.

It is intended to allow some of the bright blue to show through the freshly applied inpainting, and not to match the original paint perfectly. Curators were concerned that an entirely grey-brown sky, as the original would appear today, would make this area of the composition read as an architectural background, rather than as a sky.