For a frames conservator, making a replica frame for a painting is always a challenging project. Determining what frame is correct for the period demands extensive research in a field that is still young in terms of connoisseurship.

Fig 1. Henry Fuseli

Percival Delivering Belisane from the Enchantment of Urma exhibited 1783.

Oil on canvas, support: 991 x 1257 mm

frame: 1248 x 1510 x 108 mm, painting, in previously existing frame

Fig 2. Henry Fuseli

Percival Delivering Belisane from the Enchantment of Urma exhibited 1783

painting in new replica frame

Deciding to make a new frame

Percival Delivering Belisane from the Enchantment of Urma exhibited 1873 and its frame were examined in preparation for Tate’s 2006 exhibition, Gothic Nightmares: Fuseli, Blake and the Romantic Imagination. The existing nineteenth-century swept composition frame, in a rococo revival style, was immediately recognised as inappropriate for a painting of 1783. In addition, the frame had been reduced in size to fit the painting, which compromised its decorative scheme. To make it visually acceptable this frame would have needed to be restored to its original dimensions, but then it would no longer fit the painting. Consequently the frame was archived and a decision taken to make a stylistically appropriate replica frame.

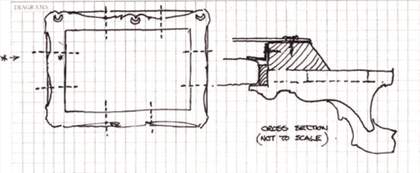

Fig 3. Diagram showing the 8 cuts where original material was removed

Fig 4. Detail of cut on the frame of Henry Fuseli's Percival delivering Belisane from the enchantment of Urma exhibited 1783

Researching a replica frame: contemporary representations of displays

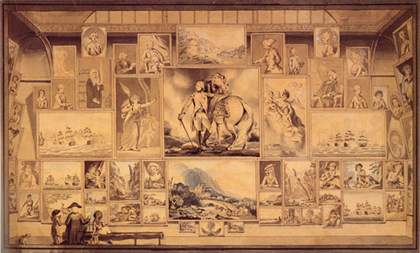

In 1784 the Royal Academy’s approach was to frame everything in temporary exhibition frames. This allowed paintings to be hung directly abutting one another. As E.F. Burney’s The Royal Academy Exhibition of 1784: The Great Room, North Wall illustrates, all the paintings were framed with simple, flat wooden borders, which are quite different from the more ornate styles used for displaying pictures in private houses. Therefore images of this type were not informative.

Researching a replica frame: other known Fuseli paintings with ‘original’ frames

Here there were three possible candidates: Ezzilin and Meduna 1779 (Sir John Soane Museum, London) Thor Battering the Mitgard Serpent 1790 (Royal Academy, London) and The Shepherd’s Dream, from ‘Paradise Lost’ 1784–5 (exh. Royal Academy 1786). The last was considered to be the most suitable as its historical accuracy of style and technique for 1783 could be confirmed by consulting the John Anderson Frames Images Archive, held at Tate. It was also the most practical, being a work in Tate’s collection, since access to the frame was necessary for the research. Conservators also had to ask themselves whether it would be technically possible to copy the frame in the time available.

Fig 5. E.F. Burney, The Royal Academy Exhibition of 1784: The Great Room, North Wall

Framed painting in centre is Fuseli's, Lady Macbeth Sleepwalking 1784

Fig 6. Henry Fuseli's The Shepherd's Dream, from Paradise Lost 1793

Oil on canvas, support: 1543 x 2153 mm

frame: 1784 x 2395 x 107 mm

painting, in its original eighteenth-century frame

Identifying the ‘original’ frame

Detective work on construction, wood identification, later additions and gilding schemes for the frame around The Shepherds Dream, from ‘Paradise Lost’ 1784–5 allowed the team to establish how that original frame was made and how it might have looked prior to later additions. It was discovered that several gilding schemes had been applied over time and that the flower corner decoration was a later addition.

Constructing the replica: a mix of new and old

In making the replica, wood-working machines were used to save time. A spindle moulder was used instead of hand planning to copy the shape of the original eighteenth-century wood profile. However, where possible, traditional techniques were used. For example, the three rows of applied decorative lime wood ornament (waterleaf, egg-and-dart and ribbon-and-stick) were meticulously carved with mallet and chisel.

Fig 7. Various stages in carving ribbon and stick decoration

Fig 8. Burnishing the water gilding

Before attaching the decorative carving to the assembled frame, everything was ‘whitened up’ by brushing several coats of a mixture of chalk and rabbit-skin glue onto the wood. After smoothing back this surface, special gilder’s coloured clay/bole was applied. It was possible to colour-match the plum and yellow clay which was the first scheme on The Shepherd’s Dream’s frame. This was important as the clay lies directly beneath the gold leaf and its colour influences the final appearance of the gold. The final step was the application of traditional oil gilding and water gilding, followed by burnishing some areas of the water gilding to a mirror finish.

Fig 9. Plum and yellow clay

Fig 11. Corner detail of finished frame

Ensuring a compatible frame

The degree to which a newly gilded frame is toned is always the subject of much discussion. In keeping with Tate’s regular practice, it was decided not to create an antique look but only to lightly tone the new, bright gilding to make it compatible with the eighteenth century painting.

This exciting project has provided Percival Delivering Belisane from the Enchantment of Urma exhibited 1873 with a stylistically faithful eighteenth century replica frame which allows viewers to enjoy Fuseli’s mysterious creation in a suitable setting.