Metadata comes in many different flavours. Alex discussed how we will use metadata to present the archival objects online in a previous blog post. Here I will look at the metadata we are using internally, to manage both the digitisation process itself and the digital resources it produces.

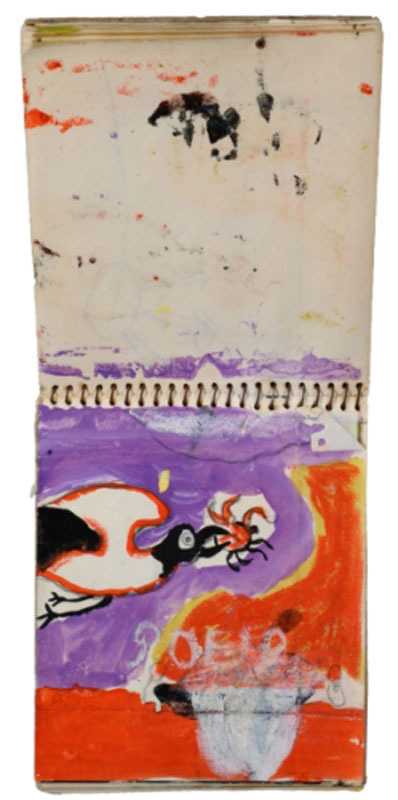

Graham SutherlandUntitled, lyre bird in flightGouache, watercolour and graphite on paperTGA 812/5© The estate of Graham Sutherland

All archives generate metadata for their collections. This normally takes the form of an archive catalogue. Catalogues serve a dual purpose, helping an archive manage its collections as well as helping users locate items they need for their research.

Archive cataloguing at Tate is based on the ISAD(G) international standard. This produces hierarchical catalogues – unlike a typical library catalogue, for example, archive cataloguing captures the relationships between items and their context, which is essential for understanding a collection. A single letter may only really make sense when read alongside other letters that together form a conversation. When cataloguing, I sometimes describe individual items in a collection, but I may equally describe groups of items at a higher level. You can see how our archive is currently catalogued online.

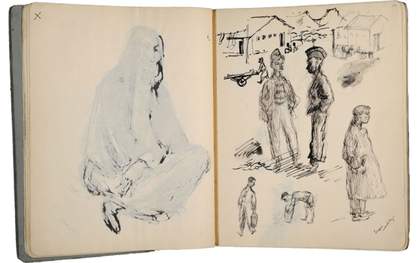

For this project, however, we need to go into greater detail and manage parts of objects, for example the individual pages of a letter. This allows us to link an individual image to the original archive item and to other related images. We also need information we do not usually capture, for example the orientation of a sketchbook’s pages, or the order of pages in a letter. All of this information allows us to organise the digital images and it will also be used to drive the display online. When we present a sketchbook online, we can now be sure that the pages we display are from the same sketchbook, in the right order and the right way up – something that is apparently simple but which requires the right metadata.

James BoswellUntitled, six studies of men and boys from a sketchbook covering Boswell's posting to Iraq 1942–3Ink on paperTGA 8224/16© The estate of James Boswell

However, even this more granular approach to archive cataloguing does not by itself produce all of the information we need for this project. We must also capture technical metadata. The project is producing a substantial digital resource – not only the images of the archive items but other material including transcriptions and films. For the project to have an enduring legacy we need to preserve this material and ensure it is available for Tate and others to use in the future. Preserving digital objects involves managing not only their storage, but also the software and hardware environment used to capture, process and access them. This requires detailed information on digital objects, including the environments used to produce them, their file formats, and relationships between them. Tate has adopted the PREMIS metadata standard to manage all of this information, and this project will give us valuable experience of a leading standard in this field.