Delightful and revealing graphics can emerge from swathes of seemingly impenetrable facts and figures. My first encounter with this phenomenon was the work of Edward Tufte at the Graphics Press in books like The Visual Display of Quantitative Information and Envisioning Information. Latterly, the Guardian’s Data Blog has popularised data visualisations, not least the work of David McCandless at informationisbeautiful.net.

Beyond the world of publishing and journalism, there is a growing public interest in data and open licensing. The availability of great free software to crunch the numbers—such as d3 and Raphaël—leads us at Tate to conclude that the time is right to share.

As part of the Archives & Access project, our legal team is working hard to identify content we can release under Creative Commons licensing.

In a parallel piece of work, we have been modernising our web infrastructure to support the new features of the Archives & Access project. This technical architecture revamp provides access to the information held in Tate’s ‘back-office’ systems via a RESTful API. Although this facility was primarily built to serve data to pages on the Tate web site, it was a logical next step to offer wider access to the same source data.

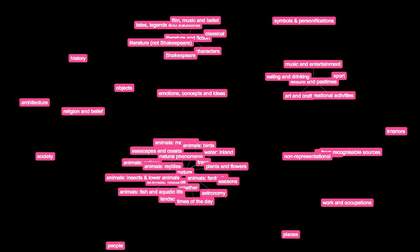

With a view to the Open Government Partnership summit in October 2013, we reached a consensus within Tate as to the type of metadata we could release into the public domain. We selected a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) licence and provided some friendly usage guidelines. The results can now be freely accessed on Github, following the fine example set by the Cooper-Hewitt . We offer rich data records for artworks and artists in a format known as JSON. This format supports hierarchical information as you might find in Tate’s subject index.

We also offer CSV ‘spreadsheets’ of our flatter data fields to allow people to play around in OpenOffice or Excel; which I like to think of as the People’s Database.

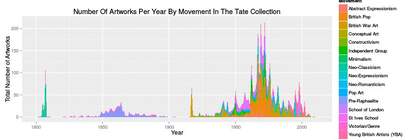

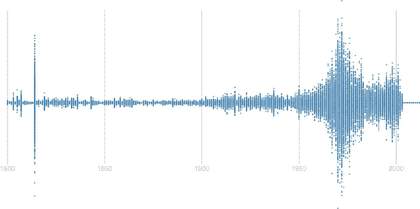

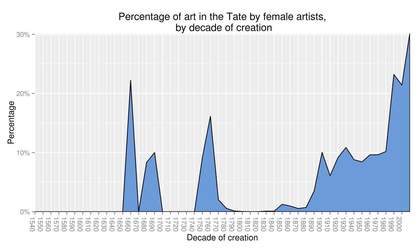

The art, programming and culture geek communities have met this data release with skill and imagination. The results are illustrated on this very page. A full list of contributions, blog posts and visualisations can be found on the Github README. Certain themes have emerged from these analyses; subjects, movements, artwork dimensions and more socially-intriguing trends such as artist gender.

As a platform, GitHub encourages hackers to submit corrections to data and suggestions for improvements, which we welcome and act upon.

In future, we should continue to answer Tim Berners-Lee’s call for ‘raw data now!‘ and look deeper into linked data. For now, I feel Tate should release its information with correct licensing as soon as it is usable. We are learning how people prefer to consume our data and we can collaboratively figure out our next step.

Contributions from across the Archives & Access project team helped us ‘free’ our data. Tate as a whole has noticed the impact of having this information analysed and played back to us from external sources. This, in turn, has prompted many internal discussions. Soon, metadata and imagery from Tate’s fascinating archive will further enrich this dialogue.