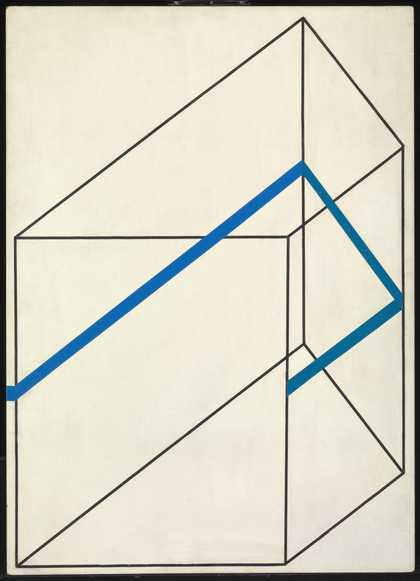

Edward Krasiński, Krzysztofory Gallery, Krakow 1965, exhibition view © Hanna Ptaszkowska and archive of Museum of Modern Art Warsaw, courtesy Paulina Krasinska and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw

He was a late starter

Although he eventually emerged to become a key figure of the Polish neo avant-garde, and one of the most significant Eastern European artists of the twentieth century, the humble Krasiński seemed in no rush.

He had studied design and later painting in Krakow before moving to Warsaw in 1954. Working as an illustrator and designer, in his spare time he developed a painting practice influenced by dada and surrealism, but later discarded painting in favour of his own innovative artistic framework. In 1965, aged forty, and more than ten years since his move to the capital, Krasiński staged his first solo exhibition.

Edward Krasinski

Untitled (1968)

Tate

© The estate of Edward Krasinski, courtesy Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw

Theatre was crucial to his work

The 1965 exhibition that marked his solo debut also announced Krasiński’s career-long preoccupation with the relationship between object, space and the beholder. It included illuminated sculptures that were suspended on thin wires in a darkened space, creating a dramatic interplay between light and shadow; arranged without any plinths or display cases, the visitors' encounter with the objects was uninterrupted.

A year later, Krasiński was among a group of artists and critics who founded the Foksal Gallery, in Warsaw, a site he would use to experiment with and refine his approach to exhibition making.

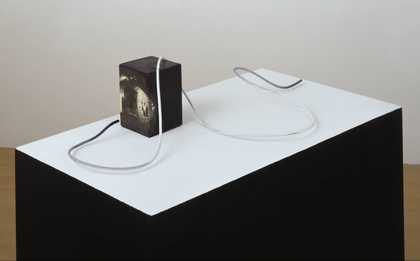

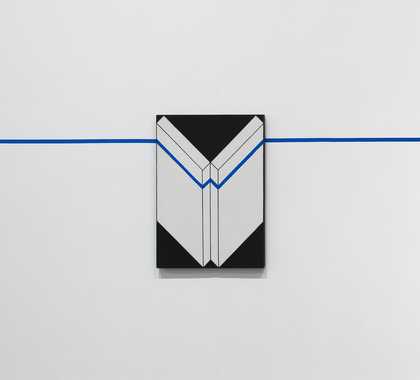

Edward Krasinski

Intervention 15 (1975)

Tate

© The estate of Edward Krasinski, courtesy Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw

The tale of the Blue tape

A trademark of Krasiński's work was his use of blue Scotch tape. ‘I place it horizontally at a height of 130cm everywhere and on everything’, he said. He first used his signature blue strip in 1968, progressing from simply sticking it in surprising places to making works that incorporated it (notably in works he called Interventions), unifying objects with the space around them. He explained:

I wanted to “pull” something out of the wall; I framed parts of reality, like a fragment of my door with the handle and the frame and made a picture out of it.

Edward Krasiński

The Studio 2004. Photo by Aneta Grzeszykowska & Jan Smaga, courtesy Paulina Krasinska and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw

His apartment doubled as artist’s studio

In 1970 Krasiński moved into the top floor apartment of the established Polish constructivist artist, Henryk Stażewski. It was a significant move which saw Stażewski introduce him to gallerists, critics and thinkers, some of whom would impact positively on his career. When Stażewski died in 1988, Krasiński filled the void left by his friend and mentor with ephemeral works and installations, as well as, of course, blue tape.

In 1989 he staged an exhibition at the Foksal Gallery called Homage to Stażewski. Featuring a recreation of the space the two artists had shared, Krasiński used large-scale photographs to represent the elements of the interior – images of bookshelves, walls and Stażewski's paintings were mixed with original artworks by Krasiński. It became a total work of art, and is currently open to the public as the Avant-Garde Institute.

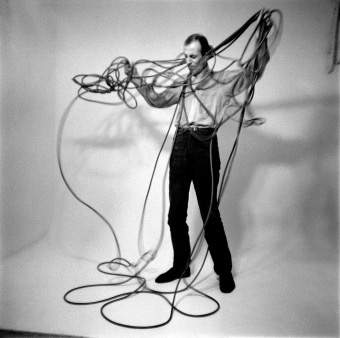

Edward Krasiński J’AI PERDU LA FIN!!! 1969 © Hanna Ptaszkowska and archive of Museum of Modern Art Warsaw, courtesy Paulina Krasinska and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw

The 1970 Tokyo Biennial

By now, Krasiński had begun to show internationally, and in 1970 was chosen for inclusion in the tenth international Tokyo Biennial, Between Man and Matter. When his works were delayed in shipping, Krasiński responded with a gesture that marked an important turn in his practice – as well as what has been said by some to herald the beginning of Polish conceptual art. The artist later explained:

I went to the post office and sent a telex repeating “BLUE” five thousand times. Before that, I had sent a telegram to Tokyo that I would send a telex at a specified time and that they should scatter the very long stripe on the podium with the earlier telegram.

This 80-metre long ‘stripe’ was duly exhibited until the arrival of the intended works. Following further instructions from Krasiński, the strip of paper containing the telex was placed in a bullet-proof glass case. Of the work's impact, Krasiński said:

After that there was nothing more I could do; it was so radical there was no turning back.