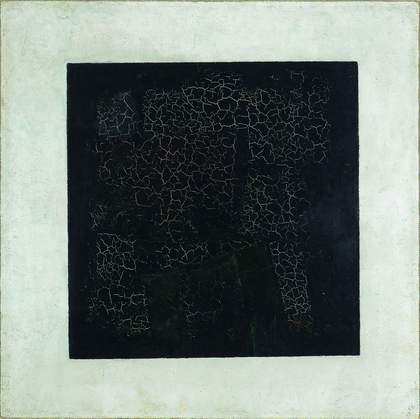

Kazimir Malevich

Black Square 1913

© State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

1. It is the first time someone made a painting that wasn’t of something

Or at least it’s often thought to be the case, and the Kiev-born artist Kazimir Malevich certainly thought so (though the dispute rages on). In a handout to accompany the first showing of the painting in the exhibition the Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10 in 1915 he wrote:

Up until now there were no attempts at painting as such, without any attribute of real life… Painting was the aesthetic side of a thing, but never was original and an end in itself.

He made his intention clear; he wanted to completely abandon depicting reality and instead invent a new world of shapes and forms. In his 1927 book The Non-Objective World, he wrote: ‘In the year 1913, trying desperately to free art from the dead weight of the real world, I took refuge in the form of the square.’

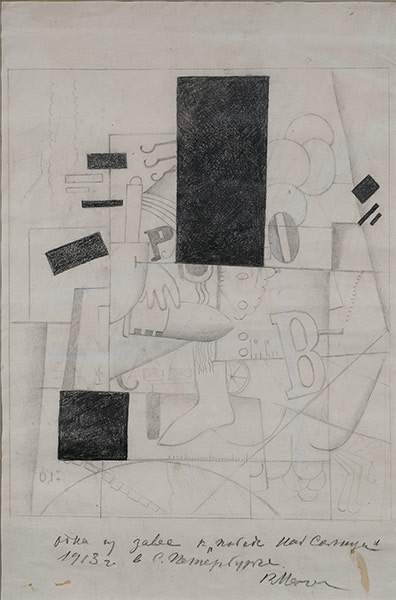

2. It began life as a stage curtain

Malevich painted four versions of the Black Square. Although the first version is dated 1913, we think he probably painted it in 1915. (Maybe he was thinking about his future reputation as the father of abstraction and wanted this radical artwork to seem earlier). But in any case, the square did first make an appearance in 1913, as the design for a stage curtain in the futurist opera Victory over the Sun.

Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935)

Sketch for a stage curtain for the opera Victory Over the Sun, 1928

Photograph: St. Petersburg Museum of Theater and Music

Malevich had been collaborating with the musician Mikhail Matyushin and the poet Aleksei Kruchenykh on a manifesto which called for the rejection of rational thought. They wanted to overturn the established systems and hierarchies of Western society. Together with poet Velimier Khlebnikov they staged Victory over the Sun, where the characters aimed to abolish reason by capturing the sun and destroying time. The libretto used Kruchenykh’s zaum – a new language of sounds that had no meaning. This sparked something in Malevich. As Tate curator Achim Borchardt-Hume puts it:

Malevich, infused with the spirit of his friend’s linguistic experiments, invented at breath-taking speed a new painterly language made up solely from shapes and colours. He called this language suprematism

The opera opened up new ideas about what art could be.

3. It’s a revolutionary symbol

Malevich called his new abstract approach to painting suprematism. Suprematism is all about the supremacy of colour and shape in painting. By sticking to simple geometric shapes and a limited range of colours he could focus on the painting itself and not be distracted by representing a scene, or landscape or a person.

Kazimir Malevich

Dynamic Suprematism (1915 or 1916)

Tate

The Black Square is not just the first painting in a new movement. It’s a totally different kind of art object to what had been seen before. Malevich promoted it as a sign of a new era of art and he saw it as beginning at zero. That’s why he added '0.10' to the exhibition title of his 1915 exhibition. (However, although he declared the Black Square as the first suprematist painting, x-rays show a multi-coloured suprematist composition underneath).

When Black Square was first exhibited, the world was in chaos. It was the middle of the First World War and there was continuing unrest following the 1905 Russian revolution that in 1917 would explode into the Bolshevik uprising and October Revolution. The Black Square arrived at a time when Russian art crowds, although used to seeing cubist and futurist works, would never have seen a work like this. The artistic revolution Malevich was bringing about seems to reflect the social revolution that was happening. Malevich didn’t intend for the Black Square to be a representation of a real thing, but a symbol of a dawning new age.

4. It was the first icon (that wasn’t actually an icon)

Malevich unveiled the Black Square at the The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10 held in St Petersburg (which had been renamed Petrograd) in December 1915. He was keen to showcase suprematism, his new idea, and Black Square was placed high up on the wall across the corner of the room. Though this position might mean nothing to the average non-Russian viewer today, it was the same sacred spot that a Russian Orthodox icon of a saint would sit in a traditional Russian home. This likeness wasn’t lost on people in Petrograd. Malevich wanted to show the Black Square to be of a special or spiritual significance, make it the star of the show and the overriding emblem of his new style.

The 2014 Malevich at Tate Modern, with a reconstruction of the original presentation of Black Square.

© Tate

Photo: Olivia Hemingway

The Black Square became Malevich's motif, even his logo or trademark. In his later work, when he made a return to figurative paintings (often of peasants and workers), he signed many of them with a little black square. At his funeral the car carrying his body had a Black Square on the front and mourners held flags decorated with black squares. A flag with a black square was also fixed above his suprematist-style coffin and it went on to mark his grave.

The black square became not only an icon of Malevich's style, but an icon of twentieth century art.

5. There’s no ‘right’ way to look at it

Within months of Malevich’s death in 1935, his work disappeared from public view and Stalin’s state-sponsored social realism was adopted as the ‘official art’ of Soviet Russia. The Black Square wasn’t exhibited again until the 1980s. It became an icon that couldn’t be seen by many and so the idea of it remained an almost mythical presence, and still continues to inspire and challenge artists and designers today. Because the square is obviously a simple motif, when you work with it, you can start to see it in different ways or think about how very simple things can stand for certain ideas.

Gillian Carnegie

Black Square (2008)

Tate

When Black Square was first exhibited people found it a strange thing and people still find it a strange object today. There’s no wrong or right way to look at it. It could be a window into the night, or you could see it as just a black shape on a white canvas, (which is more of what Malevich was intending). Malevich set out to change forever the idea that painting has to represent reality. It's intriguing to think how doing something simple or even seemingly dull, can sometimes be revolutionary. That’s what makes the Black Square a radical thing, however you look at it.