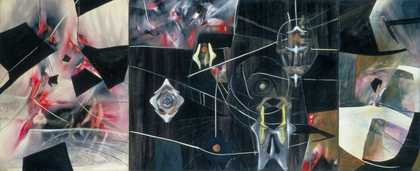

Matta (Roberto Matta Echaurren)

Black Virtue (1943)

Tate

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

To begin with, I would very much like you to talk about chance.

Roberto Matta

That is an excellent idea because I am very interested in chance. For me, it is the best of things. It is a game between series. Chance rolls on and never stops. It’s like the random button on a CD player. The numbers continually roll over and do not stop, as if they are caught in a sphere. They turn and turn and then stop by chance on a track. We are like these numbers. We are rocked and bombarded from above and below, from right and left. We are a target and bombarded from all sides. This is the administration of chance, a serial chance. Chance plays a very important role in my conception of architecture, for example.

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

How did you meet Buckminster Fuller [1895–1983, American architect, theorist, and inventor of the geodesic dome and Synergetics]? In New York in the 1940s, no?

Roberto Matta

In 1939. He was a very unusual person, rather delirious. I was very naive and very young. Sometimes, he came to talk to me at three o’clock in the morning about an idea he had just had. He was incredible and very funny.

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

Fuller and Alexandre Dorner [director of the Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover, until 1933] had a project to construct the museum of the future.

Roberto Matta

Fuller was interested in spaces like these. But me, on the contrary, I was interested in other spaces to do with forms drawn from non-Euclidean geometry and the idea of entering these spaces. These structures do not rely on the sense of space, as we know it. It is a space without limits and which transforms itself in time – a mutant space. It is the same thing with a representation of a fly’s eye, or rather the way in which a fly sees us. What it sees certainly does not resemble what we see. We are transformed in the fly’s vision. It is not a photo. And in the eye of the rhinoceros, in the eye of the serpent or in the eye of the squirrel, we are, no doubt, also different. We do not know this but it interests me to imagine it.

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

Can you speak more about your links to architecture?

Roberto Matta

You know Corbu [Le Corbusier]? I went mad in Corbu’s studio. There were three of us, an Austrian, a Japanese and me. The office was run by his cousin, Jeanneret, who was loaned by the Jesuit monastery. We had no work and were not paid, obviously. Since there was nothing to do, I produced the mad [architectural] propositions that are represented in my drawings of that time. What was good in the long run is that all of this early material has remained more or less hidden. If I had become fashionable or fallen into the media, I would have continued working on these drawings. Since there was a silence about my work, I have never stopped working. I have worked a great deal. You cannot imagine it. There are rolls of unfinished things all over here. Sometimes I find things, propositions about space, and I ask myself: ‘Ah, what was that?’

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

What are the projects you are working on now?

Roberto Matta

You know, I do not really want to speak about them. They are things of the future. And people will understand only after a revolution in geometr y, in a hundred years. Nevertheless, artists continue to work always in the same manner, working on their small arrangement taken from Euclid.

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

There is also a CD-ROM project.

Roberto Matta

Yes, this project is based on the question: ‘How do you make your own father?’ Its goal is to create a base of inspiration that anyone can appropriate and transmit in their turn, according to the principle of relay. I will give you an example. At the moment of the Pinochet affair, I made some drawings. I called them El gran burundum. I showed them to a poet and he spent a whole night writing on the drawings. He managed to produce something of his own, thanks to these drawings. He did not passively contemplate them and say: ‘Ah, that is beautiful.’ This poet was Raphal Alberti [the great 20th-century Spanish poet, 1903–1999, author of To Painting, 1947–67, a series of poems dedicated to the three elements of painting: the artists, the paintings and the materials]. What he wrote is very interesting. This is what art should be.

Resistance is in each of us. We resist by exercising our creativity. That is true poetry…to resist is to be a poet and to live an uninterrupted metaphor.

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

The CD-ROM’s format also respects and authorises the non-linear. This is what struck me when I saw your architectural drawings: these pluri-dimensional, non-linear cities. They are a premonition of things to come in urbanism.

Roberto Matta

We never know what will happen but I always had the impression that what was coming would be something terrible. We should reread Marx now. What did he want to say in his time? I think we should reread him because what we know of his ideas was transmitted to us by the unions in order to help the working class: I believe that he wanted to say that capital is communism. It belongs to everyone. And we should not touch capital. There should be enough so that everyone can have something. It is a completely different concept. And if you remove the interest of capital, you hurt capital. And there, we fall into absolute fascism. We cannot govern. We cannot give social security and all of these things. And the population will submit by laziness.

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

In this context, what does ‘resistance’ mean to you?

Roberto Matta

Resistance is in each of us. We resist by exercising our creativity. That is true poetry – when we seek new comparisons, other ways of looking and conceiving of things. Many people believed that resistance was only a union thing, a struggle that profited the unions. But unions organised the working class with promises that could never be achieved. We lived for a century with a bad interpretation of Marx.

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

That brings us back to the question of utopia. Can we establish a link between these ideas and your early projects of utopic urbanism?

Roberto Matta

I developed the project when I was a student at the catholic university with the Jesuits. At that time, in Switzerland, there was the League of Nations and I had this project, which was a sort of League of Religions. All the religions, all the theologies, all the interpretations of the question ‘Why is man on earth?’, would be united in order to find out who was ‘more right than the other’. I was 19 or 20 years old and I had this idea to make the delegations of all of the world religions converge towards the same point. Of course, I did not know all of the religions but I wanted to construct a common temple so that they would enter into discussion. There was a residence for each delegation. It was therefore an architectural project. I called them ‘aerodynamic architectures’ because, at the time, we had started to talk about aerodynamic cars. I drew models of cars after racing cars of the period. Later, I said that everyone would have a car like that - aerodynamic. Everyone said: ‘But you are mad, that will never happen.’

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

Did you write many texts?

Roberto Matta

All that I thought was transmitted by oral means. And everyone interpreted the things that I said differently. Nothing is fixed on paper. It’s better like that. To act as creator, to look for comparisons between things in order to capture them, is to invent. Otherwise, it is recitation. You repeat others. It is not what I have said that is important, it is the way that you heard it, that you understood it and the way that you will, starting from that point, move forward with your own work.

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

It is a form of education.

Roberto Matta

The problem is that in France there is a culture, a civilisation almost, of recitation and repetition. There are many scroungers. Do you know what a scrounger [glandeur] is? People who pick up the ideas that are left lying about by others and do what they can with them. The School of New York were scroungers. They took what was left from the 1920s and 1930s – a little Man Ray, a little Max Ernst – and with that they made Warhol. The only ones who count are those who create – those who propose non-Euclidean geometry, such as Einstein. But nobody does that. To do that would be to change things a little. But when you take a little Man Ray and then take a photo of Marilyn Monroe, you are nothing but a scrounger. It is the philosophy of ‘pick and mix’ that was mostly adopted from the 1920s and 1930s. So, to resist is to be a poet and to live an uninterrupted metaphor. That means doing and saying different things all of the time and each time.

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

Did you know Gilles Deleuze [philosopher, 1925–1995]?

Roberto Matta

I knew him a little but I knew Flix Guattari [psychoanalyst and political activist, 1930–1992, author with Deleuze of Anti-Oedipus: Captialism and Schizophrenia, 1972] very well. Because since the beginning, I have spoken about psychological morphologies. For a long time, I have known that geometry is not within everybody’s psychology. They read, as it is possible for them to read, by projecting their own images. They read with their own images and not with the images that the author wants to impose on them when he writes. I have a quite logical example. Slaves and the church say that the woman is a flower. But she is not a flower because each woman is an erotic dream. Even the Virgin Mary was an erotic dream, who called the Holy Spirit and finished up having his child [laughs]. It is true! And thus, each one has his erotic dream. But what do we know? We can only imagine what the dreams of others are by looking at our own. It is the same thing with trenches [in war]. How do you represent them? How do you imagine the trenches? They were sewers, because it rained all the time. Do you see it like that?

Roberto Matta

Is there a link between your vision of the trenches and the analogy that you made between the trenches of the First World War and the modern world?

Roberto Matta

Yes there is; first of all, because cities are constructed in the countryside. This is also more or less what Le Corbusier thought. Only Corbu was unlucky and they transformed public housing into barracks. He had a completely different idea, he said: ‘We must give the earth back to pedestrians.’ Cars and the rest, he did not really know where to put them. His answer: ‘At any rate, not in the streets.’ Architecture should rest on the ideas of Einstein and new geometry. Man is constantly changing and everyone should understand that others change as we change. So, there should be no edifices, no possessions – there should only be the ephemeral. It is like football.

Hans-Ulrich Obrist

Like football? What does that mean?

Roberto Matta

What I mean is that when you play football, you win a match but that does not mean you have won for all of your life. Next time, you might lose. But we have difficulty understanding that. We tend to believe that once we have obtained something, it is ours forever.

The artist’s biography

Roberto Sebastian Echaurren Matta was born in 1911 in Santiago, Chile. After earning a degree in architecture, he travelled to Paris where for two years he worked in Le Corbusier ‘s studio. During a visit to his aunt in Madrid in 1936, Matta met the poets Pablo Neruda and Federico Garca Lorca, who introduced him to Salvador Dal and Andr Breton. Breton was impressed enough to buy several of Matta’s drawings and in 1937 invited him to join the Surrealist group, which led to his participation in the 1939 International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris. Influenced by his association with the Surrealists, Matta began to develop his own visual language and, with his early works, the Inscape series and the Psychological Morphologies, which explored themes of cosmic creation and destruction. The outbreak of war in 1939 drove Matta into exile in New York. Alongside Max Ernst, he began working with Art of the Century, Peggy Guggenheim’s influential gallery, where he exerted a strong influence on the emerging Abstract Expressionist painters. During the 1940s, Matta’s work featured machine-like and invertebrate shapes interacting in a dynamically charged cosmic space. In 1948, Matta returned to Europe and parted from the Surrealist group. He went first to Rome before settling in Paris in 1954. During the 1960s and 1970s, Matta travelled extensively in Africa and South America. His works can be found in many of the world’s most important museums and he held solo exhibitions at MoMA, New York, the Hayward Gallery, London, and at the Muse National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, among others. Although he is best known as a painter, Matta also worked with alternative media. He died in Italy, on 25 November 2002.