TateShots visits St Ives to look around the Peter Lanyon exhibition at the Gallery in 2011. Lanyon was one of the most innovative figures in twentieth-century British art and saw himself as remaking the tradition of landscape painting, using landscape to express ideas about states of being and the human condition.

The exhibition’s curator Chris Stephens takes us on a tour of the show, and explores two of Lanyon’s most famous works: The Yellow Runner and St Just 1946

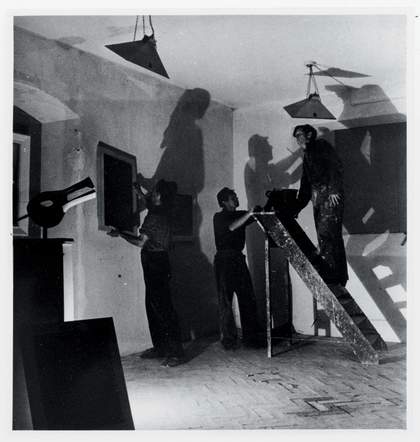

Lanyon saw himself and explicitly associated himself with the landscape tradition, with the tradition of Constable and Turner in British art. But crucially, he didn’t paint landscape as seen from a particular place, not as seen as if through a window or through a lens; he wanted to paint landscape both from many points of view, many visual perspectives, but also conceptually from different perspectives. So his painting of St Just, for example, is about the history of that place, about the people of that place, about the exploitation of the miners, about the sense of landscape as carrying in it the history of its people. He names it after the town of St Just, which is the centre of the tin-mining industry in West Cornwall, and at the centre of it, one of the last things he paints is this long black shaft, which he says refers to the mineshaft in the landscape around the place. But he also says it’s like a crucifixion – the shaft becomes the cross, the barbed wire at the top of the mineshaft becomes the crown of thorns.

The landscape also attracts him in that he is fascinated particularly by the cliffs. He talks about being drawn to places where solids and fluids meet, and I think there is a great clue to his art there, his fascination with points of conjunction and distinction, sea and cliff; also where two bodies meet. There is often a figure embedded in Lanyon’s paintings. And again, his fascination with the phenomenological experience of being in a place, his fragile body being out in extreme weathers, and then ultimately gliding, soaring into space like the gulls that he had watched for many years. It’s very much, again, about that meeting of solid and fluid, his fragile solid body and this great amorphous space. And of course, tragically, that is the cause of his death – Lanyon died in August 1964 as the result of a gliding accident, aged only 46.