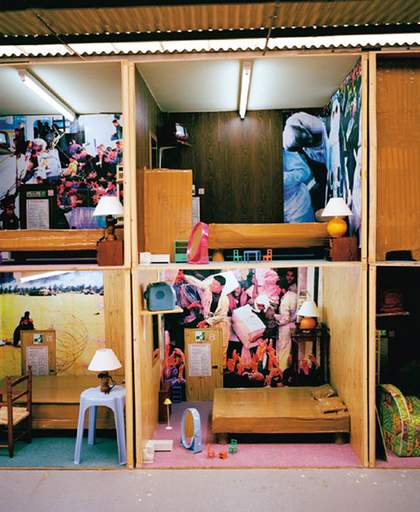

In his Paris studio Thomas Hirschhorn is putting the finishing touches to a model hotel. But it’s not like any place you’d want to stay in. Propped up on an uneven foundation of pallets and trestles, the two-storey structure exudes a rather clumsy shabby chic, fusing the look and feel of a home-made doll’s house and the poster-plastered walls of a teenager’s bedroom with the spatial sensibilities of a battery chicken farmer. You might argue that the model emphasises content rather than form, but while the rooms are filled with furniture and the walls papered with images, the end result is an awkward and unsettling mix of styles and scales. Some of the beds appear to be carefully crafted miniatures; others are blocky objects made from cardboard and masking tape. (Not to mention one rather indescribably shaped armchair-type object.) Thomas Hirschhorn is the ultimate cowboy builder.

Thomas Hirschhorn

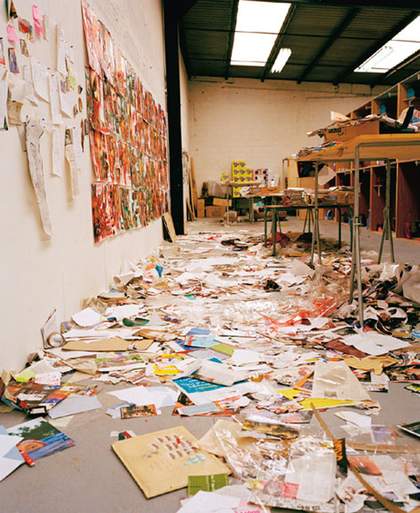

The artist's studio in Paris

Photograph by Norbert Schoerner

Over the past decade and a half the 46-year-old Swiss-born artist has created a series of structures – among them kiosks, altars, huts, assorted monuments and even a launderette – out of seemingly amateurish accumulations of cardboard, plywood, plastics and tinfoil. Most of them are held together by a paranoid, almost frenzied, application of masking tape (rolls and rolls of it). But ironically this serves more to emphasise the work’s fragility than to provide it with any structural strength. ‘I am not interested in “quality”,’ says Hirschhorn. ‘I am interested in “energy”.’ And while you wouldn’t want him supervising your loft conversion, his cheaplooking ramshackle constructions have made him one of the art world’s rising stars.

According to Hirschhorn, ‘art exists as the absolute opposite of its time – as the absolute opposite of the reality of its time.’ And through his own work he seeks to show that there is more to this opposition than the fact that the context of art makes it possible to celebrate the kind of shoddy building that people living in the real world would not tolerate at all.

Thomas Hirschhorn

Photograph by Norbert Schoerner

Thomas Hirschhorn

Photograph by Norbert Schoerner

World Airport, created for the 1999 Venice Biennale, is one of Hirschhorn’s biggest and best known artworks. And it draws together many of his central concerns. At its heart is a world map, redrawn as a rank of crudely made model aircraft, each branded with the colours of a different national airline. Around it all is a somewhat bewildering network of texts, images and handmade objects, incorporating representations of commercial brands that dominate the world economy – a giant Nike trainer and ranks of anonymous Ford motor cars – alongside tributes to socialist martyrs and campaigners for workers’ rights – such as Rosa Luxemburg and Antonio Gramsci.

As a whole it is overwhelming and rather difficult to take in, but perhaps that provides a more accurate snapshot of the world and its troubles than the more simplified daily image of cheap flights, instant global connectedness and a never-ending supply of factory-made consumer goods ever could. Somehow Hirschhorn’s comic constructions have a habit of appearing more real than reality ever does. Perhaps indeed he is telling us that in the real world we tolerate too much. Irritatingly though, it only takes one more look at his crappy construction style to make you wonder if that might be interpreting too much.

Before becoming an artist in the mid-1980s, Hirschhorn had trained and worked as a graphic designer. Yet despite the ease with which he has managed to turn everyday materials and plenty of masking tape into a signature visual style, and the fact that he describes his work using design words such as ‘displays’ and ‘layouts’ rather than the more conventional (but perhaps less meaningful) art term ‘installations’, he claims that his graphics training did not have any direct impact on his art. ‘No training helps you make your work as an artist,’ he says. ‘No training helps you to take decisions. No training helps you to make a choice. I decided to work as an artist because only as an artist can I be totally responsible for what I do. The decision to be an artist is the decision for freedom. Freedom is the condition of responsibility. To be an artist is not a question of form or content; it is a question of responsibility. To work as a graphic designer means to do what certain people want you to do. To be a graphic designer means not to be totally free and absolutely responsible for what you do.’

Thomas Hirschhorn

Hotel Democracy, detail

Photograph by Norbert Schoerner

Thomas Hirschhorn

Hotel Democracy, detail

Photograph by Norbert Schoerner

The model in his studio is called Hotel Democracy, one of two new works that will be shown in Common Wealth at Tate Modern. Its rooms are lined with media images relating to struggles for democracy around the world. And it is in such struggles that Hirschhorn finds a parallel for his art.

At one point during Tate’s studio visit his reflection in one of the hotel room mirrors stands in for the fighters and protesters that fill the rest of the walls. ‘Freedom is what I am fighting for,’ he says, ‘and I think you only get freedom when you are fighting for it. The artist is a fighter for absolute freedom.

‘The decision to be an artist is absolute and for eternity,’ he continues. ‘That has nothing to do with romanticism or idealism. It is a question of courage. I want to be courageous. An artist has to be courageous. Because he or she fights for the impossible, he or she has an impossible mission. It is impossible because there is no exit. No exit out of the world.’ The emergency exits in Hotel Democracy utterly shatter the illusion that it might represent anything real. They are nothing more than crudely drawn outlines on the building walls.