I’ve never given Tracey Emin much real thought. Until a few weeks ago I passed her off as the artist who displayed her bed in the Tate and lurched about pissed on TV. I’m of a mind to blame celebrity for this, because of course Tracey Emin is a celebrity. A big one. The kind who only has to sneeze to make it into the red tops. I’m not immune to her fame. I’ve had my fair share of celebrity thoughts about her. They’re not all that interesting. Here are some: ‘She looks like Frida Kahlo’, and ‘I wonder what she’d be like in bed?’ and ‘She must be worth a bloody bomb’ (I did warn you). But as for real live-and-kicking ideas, actual neural sparks, genuine considered opinions about Emin as an artist, well, they have been a bit thin on my intellectual ground.

So here’s where I begin. These thoughts aren’t entirely worked out yet. I’m still in a process of discovery. But then you probably are too. So what you’re about to read is a sort of travelogue of ideas, a trip across my mind as it considers Tracey Emin. You’ll add in your thoughts and feelings and if we’re lucky we’ll get somewhere by the end.

My first thought isn’t very out of the ordinary. You might have had it too. In fact, if you’re reading this, you probably have. It’s this:

I don’t know whether Tracey Emin is a great artist.

I say this thought isn’t very out of the ordinary, but you won’t see it written down in many places. On account of her celebrity, Emin gets very little serious or considered attention from the art world. What you will see is a lot of knee-jerking.

Crude, primitive, uninteresting, ill-informed, objectionable. All these words have been used in print to support the opinion, held by many, that Tracey Emin is a worthless con-artist. These words: fresh, primitive (again), direct, genuine, have all been used in print to support the opinion, held by many, that Tracey Emin is a genuinely great artist. So I will not use any of those words myself and I will not tell you whether I think Tracey Emin is a great artist. Because, as I’ve said, I don’t know.

What I do know is this. Since I’ve started thinking about Tracey Emin’s work, I’ve come to appreciate it more than I thought I would. A lot more. Certain of Emin’s monoprints are etched in my head. Her blankets have popped up in my mind’s eye while I’ve been sitting on the bus. But then, Emin’s insistence is part of her power. She demands to be regarded. And this explains why the Tracey Emin Celebrity Phenomenon gripped me long before I allowed her art to do the same. Her power unnerved me. I didn’t know what to do with it but to unhook it and hang it on a safer peg.

Honey Luard, Emin’s exhibition organiser at White Cube, her London gallery, says, ‘Tracey’s art presents the world in a way you haven’t seen it,’ which is true but not quite the whole truth. At its best, Emin’s art presents the world in ways you’ve always known about but never admitted, or you’ve never wanted to admit, or never perhaps until that moment articulated. If it’s any good, art does this. It acts as the key to an unopened cupboard in some remote corner of your heart, a cupboard you once filled then locked some time so far distant the memory of it is like mist. Once the cupboard is open you can’t close it again. The memories and objects and images it contains have already spilled out and are lying there in a confused and half-familiar tangle.

Not all Emin’s work draws me like this. But when it does, my sense memory is summoned in ways that are emotionally challenging, even dangerous. Emin is dangerous. She shouts, she often bullies, she will not let you look away. At the same time, her work radiates vulnerability. At times it is even delicate. A sense of accompanied loneliness pervades the monoprints and blankets; the remote, often truncated figures struggling to claim their place on the paper, the raging words sewn on to pretty fabric backgrounds. Paradoxically, its intimacy comforts me. Here’s the thing about Emin’s art. It is comfortingly dangerous. It is at one and the same time subversive and conservative. I like this contradiction. I don’t fight against it. It gives her work its dynamism and context. It allows her to reach beyond the academy. It tells of life the way life is. Most of all, it keeps me interested.

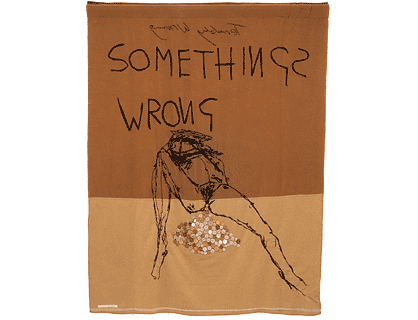

Since giving Emin’s work the time it deserves, I have been very taken with a series of monoprints from 1997 entitled Something’s Wrong. Here there are forlorn figures surrounded by space, their outlines fragile on the page. Some are complete bodies, others only female torsos, legs splayed and with odd, spidery flows gushing from their vaginas. They are all accompanied by the legend ‘There’s Something Wrong’. The series sets off in me an overpowering anxiety, a sense that we cannot always think our ways out of our bodies, that our bodies are uncertain companions. These drawings, and their lost, vulnerable legend, conjure memories of times when my own body – and specifically those mysterious parts of my own body that are concerned with creating new, other bodies – has behaved in unexpected and unmanageable ways. They remind me of how intensely lonely it can be to live inside a body. And I don’t think their power is wholly female. They bring back memories of stories I have heard about other bodies, reminding me of something a lover told me a long time ago. As a child, this man found a cyst on his penis. Troubled by the thing, he eventually squeezed it out and kept it for years in a matchbox. He would look at it from time to time and worry that it was his penis’s brain. The worry became an obsession, and the idea that he had lobotomised his own member lived deep inside the boy and refused to leave him. The cyst was always there in its box to remind him of his foolishness and his very secret betrayal. There, you see? For the past ten years or so that story has been in the mental cupboard that was opened when I looked at Emin’s monoprints. And now it is out.

The source of these drawings’ power is the mysterious and slightly sinister connotation of the phrase ‘There’s something wrong’. What’s the something? We don’t know. It’s just a sense, some rather murky aura emanating from the image. What’s wrong? Anything and everything? Emin only hints. It is up to us to imagine. I want to think some more about Tracey Emin’s artistry as a writer. Why does this aspect of her work get so little attention? Perhaps it’s because the literary and visual arts are so often held apart, two arms of a compass destined to travel in the same direction but never to meet. For the most part, writing appears in visual artworks as typography. When visual art appears in the midst of writing we assume it’s just illustrative. Emin closes up the compass. She challenges us to think of writing as visual art and visual art as a kind of text.

There’s no doubt Tracey Emin loves words. She is quite maternally protective of the alphabet. When I visited her in her studio for this piece, she was gathering all the ‘spare’ letters she had cut from fabric over the years and not yet used and sewing them on to a blanket so as not to waste them. Emin had allotted her letters an orderly space on the blanket. She had arranged the letters alphabetically and had cut out a ‘G’ and a ‘Q’, which had been missing, to accompany the rest. Looking at that blanket I felt I’d learned a great deal about the considered and conservative fashion in which Emin constructs art from the giant, and sometimes ugly, tangle of her life. Words, letters, writing are Tracey Emin’s order.

It’s not easy to write as open-endedly as Emin does without losing the sense of the language. It’s not easy to scoop out such numinous sentences. Here too, Emin is comfortingly dangerous, insisting on the meaningful authority of both the words and their author, but also displaying a more subversive recognition of the importance of what is not said, of what can only be felt through the space between the letters. Her sentences are celebrations of words and their shapes, and because this is Tracey talking, anxiety creeps in and out of those shapes as clearly as if the words themselves were watching their backs:

Did you see Tracey?

Yea, she was Running Over black friars Bridge – it was

12 at night – she was wearing a Face Mask – And a small

oxygen tank – on her back.

Aprarently [sic] she swims with it.

Does she still Look beautiful?

NO SHE LOOKED STUPID

No she looked LIKE A FOOL

So here’s Tracey doing her thing, chasing over London’s Blackfriars Bridge and looking ridiculous. And this brings me to something important about Emin and her work. It’s important but it’s difficult to say without being misconstrued. You see, Tracey Emin is narcissistic. And by that I don’t mean that she loves herself. I mean that Tracey Emin loves an image which may or may not be herself but of which she can never be sure. I mean that Emin only half recognises her own projection. And this, of course, is why her work is so lonely, so furious and so demanding of attention. When you look at Tracey Emin’s work you see the artist struggling to reach herself, compelled by her own self-consciousness to fail and condemned by the self-same thing to begin again. What you see up on the wall or in the bed or on the screen is Emin’s own reflection, exiled.

As a result Emin has been criticised for being nothing more than a biographical documentarist, concerned only with the mundane minutiae of her narcissistic personality. ‘It’s so unmediated, I wonder if it’s art,’ says Julian Stallabrass, a critic of Emin’s work. But that is both to misunderstand and to miss the point. While it’s true that little of Emin’s work is a commentary on the business of art itself, Emin is herself the mediator between her experience and its expression. The human world consists in individual lives lived and the connections between them. By exposing her own life to public view, Emin makes those connections. Anxiety, neediness, powerlessness, exhilaration, tenderness, the fear that one is condemned to live inside a reflection of oneself, attached only to the image. Who hasn’t felt these things? Who hasn’t looked in the mirror and thought, ‘There’s something wrong’?

A while back the press pounced on Emin for her monoprint We Killed the Fucking Dinner Lady 1995, which suggests that she conspired with a friend to polish off Mrs Edwards, the dinner lady at her school in Margate. In various interviews Emin had talked about having done the same. But a journalist discovered that Mrs Edwards had not in fact been killed. And that maybe there wasn’t even a dinner lady at that school called Mrs Edwards. And so the journalist concluded that Emin was a fake. I can imagine Emin herself was faintly amused and disgusted by this. Just because her art appears to be literal, who says it’s to be taken literally? Her work draws on shifting impressions, on memory and the exigencies of narrative. She edits, reinvents, imagines. She is above all a storyteller and her stories are embroidered, both literally and metaphorically. As Emin herself says, ‘Of course everything I do is edited, considered and its final production very much calculated.’

It is partly this unapologetic insistence on her own status as an artist that gets Emin into trouble. I spoke to a number of critics for this article. When I asked them, ‘Is Tracey Emin a serious artist?’ many of them replied, ‘Well, she thinks she is.’ I was offended on Emin’s behalf by such aggressive condescension. It was as if, by her own very un-English and unfeminine immodesty, Emin had somehow given up on the right to be taken seriously. The critical establishment appears heavily divided along gender lines. Male critics tend to be more puzzled by Emin than their female counterparts, and more likely simply to write her off. Reading the clips by male commentators, I was struck by how effortlessly and habitually they patronised her. In Philip Hensher’s review of Emin’s show You forgot to kiss my soul in the Mail on Sunday last year, he wrote: ‘All perfectly nice’, ‘rather sweet’, ‘ditsy charm’ and ‘adorable’. (He didn’t like the show, incidentally.) Often the condescension comes over in small, almost indiscernible ways. Two male critics I spoke with insisted on mispronouncing Emin’s name. She became ‘Ermin’ and ‘Eemin’ respectively. My sense was that these were unconscious gestures, but whether they were or not, they were indicative of some covert desire to discount the woman and, by implication, her work.

Emin tends not to rouse such negative passions elsewhere in Europe or in the United States. Plenty of critics outside the UK don’t rate Emin’s work, but neither do they seem compelled to launch personal attacks upon her. Thinking about this, I wonder if class hasn’t got something to do with it. Tracey Emin’s virulent working-classness confuses the British art world. She’s often labelled inarticulate, even stupid. This is then used in evidence against her as an artist. When I spoke to Sir Roy Strong about Emin, he said, ‘Whenever I’ve heard her interviewed she sounds illiterate and ill-informed.’ There’s often a kind of desperation to these accusations. During one of my discussions with a critic who’d best remain nameless, I mentioned the 19th-century working-class poet John Clare, who more or less taught himself to read. I’m a great admirer of Clare’s work and I used his case to impress on the critic that a formal education doesn’t of itself constitute artistry. The critic took a deep breath, sighed, and snorted that although s/he knew more or less nothing about Clare, s/he was absolutely sure Clare had read Shakespeare and the Bible (King James’s version, natch) and listened to lots of classical music. I had a good laugh about that! Of course it’s true that Emin does not express herself in the same way as someone middle class or with a university education. And she is the first to admit that her knowledge of art history is limited. But, as she regularly proves by her appearances on radio and TV, she is perfectly articulate when she wants to be.

The fact is that Emin infuriates the British art critical world because she plays up to it while at the same time disregarding it. And while she doesn’t flaunt her money, she doesn’t exactly keep quiet about it either. Emin is very well off. She relishes her commercial success with all the enthusiasm of the once-impoverished. And we in Britain don’t like that. In the arts especially, it’s still not quite done. Unsurprisingly, Tracey Emin is no respecter of these kinds of polite, bourgeois sensibilities. She is charmingly proud of her ‘architect-designed studio’, her AEG washing machine, and her home, a 450-year-old Huguenot house in Spitalfields, east London, which she shares with artist-boyfriend Mat Collishaw. (There’s a weaver’s cottage at the back where Emin’s ex-boyfriend, the curator Carl Freedman, lives. I didn’t ask her, but I’d be willing to bet Freedman doesn’t pay much to live there. Emin is notoriously loyal and generous towards her friends. A few, including ex-lover Billy Childish, who sold private photographs of Emin, have not returned her loyalty. It is a measure of her emotional spaciousness that she continues to think well of people until they give her good reason to think otherwise.) She has done ads for Bombay Gin and Becks beer. She will tell you quite openly that the reason she hasn’t finished her long-overdue book is that she can make more money from her blankets. Which is not to accuse Emin of being greedy or unconcerned with her artistic reputation. It is simply to say that she sees no necessary contradiction between being good and being rich.

That said, I think Emin’s work isn’t always good (though I do think it is always interesting). The piece that made her famous, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-95 1995, leaves me cold. I have thought about why I don’t like it. It’s the tent. For me, the tent is too crudely symbolic. The tent is womb, home, exile, intimacy, loneliness done out in nylon. Where’s the mystery in the tent? I’m not altogether keen on a handful of Emin’s video pieces, either. Some are ill-disciplined and a couple straightforwardly bullying. In How It Feels 1996, she rambles formlessly on about her abortion, a particular trauma in her life, as though entitled to bore and have the viewer attend. But, then again, there are other video works I find astonishing. Emin’s sketch Why I Never Became a Dancer 1995 is a Roman candle of a work, evanescent and charming, so redolent of lost childhood I found it agonising and wonderful to watch. And it hasn’t left me even now.

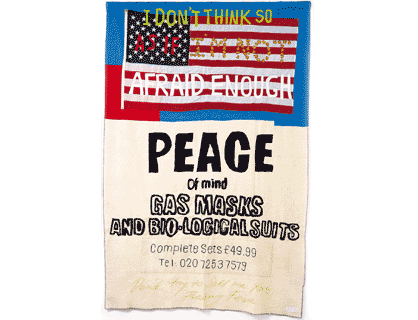

When I went to see Emin in her studio, she was hard at work at a blanket based on an incident that happened just before her birth, when her heavily-pregnant mother had been spat at in the street in her home town of Margate and called a nigger-lover (Emin’s father is Turkish). Beside this blanket lay another, waiting to be shipped off to New York for Emin’s September show at the Lehmann Maupin Gallery. It was this blanket that attracted me because it seemed to signal a shift away from Emin’s habitual autobiographical terrain. She said herself that it was ‘not like the things I usually do’. She had titled it Don’t Try to Sell Me Your Fucking Fear, and it was intended to be her comment on September 11. On it she had sewn the words of a flyer for biohazard suits and gas masks which someone had handed her on the concourse of Liverpool Street Station just after the attacks. I asked her to explain exactly why, of all the images of September 11 that were and are available, she had settled on this one. She told me she’d pictured herself and Mat walking down the road in biohazard suits, then remembered their cat, Docket, and saw herself trying to fit Docket into the biohazard suit only to have him scratch his way out. She’d then grown fearful for Docket’s health and imagined having to have him rendered unconscious so that he wouldn’t escape. But what if the attack went on for a while? It would scarcely be fair, even if it were possible, to keep Docket unconscious all that time. So a special biohazard suit would have to be procured for Docket, which is when she thought ‘Don’t sell me your fucking fear’.

I mention this because I think it says a lot about the way Emin is likely to develop. Only eight years ago the artist was assembling a collection of memorabilia called, straightforwardly, A Wall of Memorabilia for her first solo exhibition at White Cube, My major retrospective 1994. Though the title of the show was clearly a pun, A Wall of Memorabilia was itself not particularly visually arresting (Emin is not, by her own admission, the most visually gifted of artists), nor was it particularly artistically coherent. I think Don’t Try to Sell Me Your Fucking Fear demonstrates that she has moved on some way since then. Her art remains located somewhere between the search for a self and its performance, but she seems to be willing and able to formulate her experience more broadly now, without having to produce its physical signifiers. Emin isn’t likely to leave her life behind any time soon, but she is beginning to integrate other, wider elements into its expression. That is how a story about a leaflet and a cat becomes a comment on the atrocities of September 11, and a powerful one at that. Which, in turn, brings me back to my first thought: I don’t know if Tracey Emin is a great artist – but I know she’s taking a long, strange trip through my mind.

A handwritten text published in Tracey Emin: I Need Art Like I Need God (London: South London Gallery, 1997).

About the artist

Margate’s most famous daughter, Tracey Emin was born in London in 1963. She graduated with a first in fine art at Maidstone College of Art in 1986, and was awarded an MA in painting by the Royal College of Art in 1989. Her first solo exhibition, at White Cube, London, in 1994, was entitled My Major Retrospective, and she opened the Tracey Emin Museum in Waterloo the next year. Her solo exhibitions have included Stockholm, Brussels, Istanbul, Helsinki, Paris and Berlin, and she was nominated for the 1999 Turner Prize. Her most recent solo exhibition, You forgot to kiss my soul, was at White Cube last year.