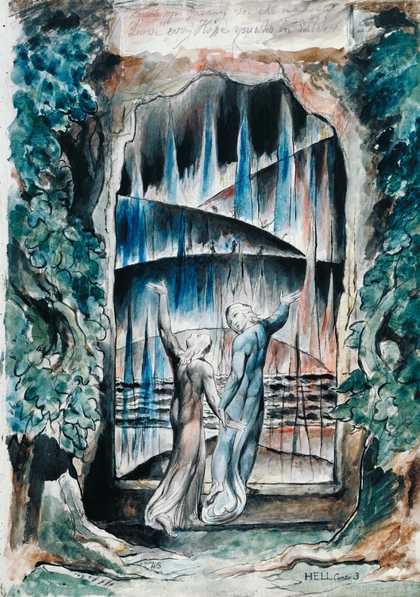

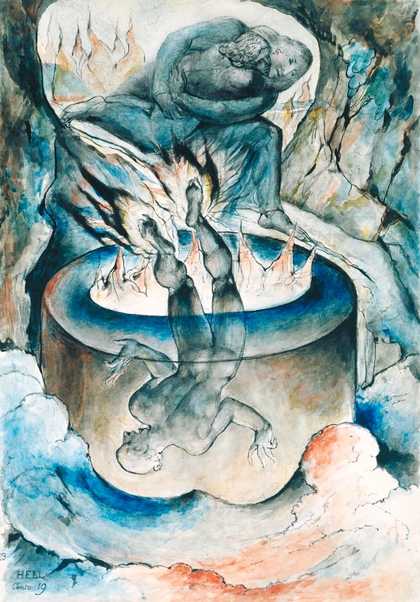

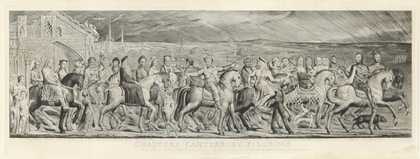

Dante Alighieri 1800–1803N

© Manchester City Galleries

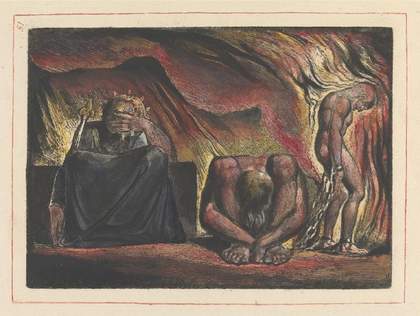

In 1824, Blake’s friend the artist John Linnell, commissioned him to make a series of illustrations based on Dante’s Divine Comedy. Blake was then in his late sixties. A contemporary account informs us that he designed 100 watercolours of this subject ‘during a fortnight’s illness in bed.'

Here you'll find seven illustrations from Hell, Purgatory and Paradise. Each picture is accompanied by an explanation and an original audio recording from the 1812 translation of Dante that Blake himself used when making his designs. So this is your chance to learn not just about Blake, but also about the Florentine poet Dante Alighieri (1265–1321).

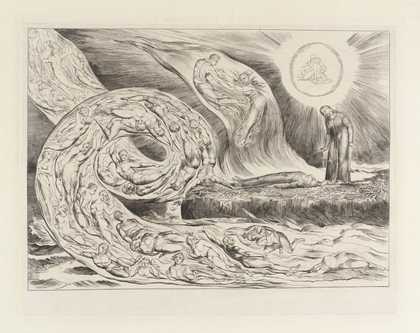

Hell, Canto 1

William Blake

Dante running from the Three Beasts 1824–7

© National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia

…My weary frame

After short pause recomforted, again

I journey’d on over that lonely steep,

The hinder foot still firmer. Scarce the ascent

Began, when, lo! a panther, nimble, light,

And cover’d with a speckled skin, appear’d;

Nor, when it saw me, vanish’d; rather strove

To check my onward going; that oft-times,

With purpose to retrace my steps, I turn’d.The hour was morning’s prime, and on his way

Aloft the sun ascended with those stars,

That with him rose when Love Divine first moved

Those its fair works: so with joyous hope

All things conspired to fill me, the gay skin

Of that swift animal, the matin dawn,

And the sweet season. Soon that joy was chased.

And by new dread succeeded, when in view

A lion came, ’gainst me as it appear’d,

With his head held aloft and hunger-mad,

That e’en the air was fear-struck. A she-wolf

Was at his heels, who in her leanness seem’d

Full of all wants, and many a land hath made

Disconsolate ere now. She with such fear

O’erwhelm’d me, at the sight of her appall’d,

That of the height all hope I lost.