Joshua Woolford, Live Performance at Tate Britain. Photo by Mika Kailes

How can sound be used to surface untold or hidden stories surrounding artworks? Does sound allow us to form new relationships with and connections to art?

Responding to these questions throughout a year-long artist residency, Joshua Woolford has created six new sound pieces for the Tate Britain collection. Throughout their residency, they have explored the potential of sound to create dialogues with artworks through talks, sound pieces and live performances.

Manifestation

Oscar Murillo

Manifestation (2019–20)

Tate

© Oscar Murillo, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner. Photo by Jack Hems

My name is Joshua Woolford and I’m currently the Interpretation artist in residence here at Tate. I’ve been working on a series of sound-based responses to some of the pieces on display around the gallery, of which this piece - Manifestation by Oscar Murillo - is one.

The sounds you can hear accompanying my voice are excerpts taken from the first Creative Storytellers workshop I hosted with Prim here at Tate Britain. During the workshop I guided a group of young people in responding to this piece through storytelling, electronic and acoustic instruments.

Manifestation belongs to a series of works by the same name which the artist has been working on since 2018. Oscar uses oil paint, oil stick, cotton thread and graphite which are all applied to a surface of canvas, velvet and linen which he hand-stitches together to create a mixed-media piece with a rich variety of textures. If you look closely you can see where the different materials have been sewn together, forming subtle vertical and horizontal lines behind the painting.

Oscar is known to work on the floor of his studio while creating large-scale pieces like this. This way of working introduces additional marks and traces such as dirt from his shoes which builds up on the surface as he walks across the piece during the painting process. He talks about the layering of visual information and traces as an ‘accumulation of energy’ which builds up over time.

Oscar was born in La Paila, Colombia and moved to the UK with his family as a child. His practice includes drawings, sculptures, films and performances which deal with themes of identity, community and binaries. He was one of the joint Turner Prize winners of 2019 alongside Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Helen Cammock, and Tai Shani. Together they decided for the first time in the awards’ history to split the prize in an act of community and joint recognition.

Oscar has described himself as being porous, he has dedicated a lot of time to studying art history in order to contextualise his practice and develop a deeper understanding of art-making and materiality. He explains how this knowledge can at times present obstacles for taking an experimental approach - that the knowledge may encourage you to lean more toward tried-and-tested methods. Because of this Oscar is actively pushing back to ensure his work remains intuitive and expressive.

While looking at this piece I experience the gestural marks almost like a layering of different mental states. The variation in colour and density of line work seems to embody this: from the lower-central section - which appears to offer a window through to the very beginnings of the piece, to this almost cyclical motion whirling around the rest of the canvas, dominated by black and dark burgundy. Sharp reds burst through on the left hand side of the canvas, and deep blue on the right. The exaggerated zig-zag form makes the piece appear to be in a constant state of motion.

Something I love about this piece is that it is extremely expressive. The large, dynamic movements and heavily saturated colours are loaded with energy. I imagine that each mark could contain a range of emotions. Or that each layer is like a page in a diary, documenting the experiences of one day at a time.

I also feel a sense of urgency, a choreography of movement and gestures which will have taken the full body to achieve. Demonstration and protest are important acts of resistance which the Manifestation series talks to which is where I think this sense of urgency comes from. There’s a seductive complexity in the variety of materials, marks, and emotions triggered. Little flowers are exposed through omission in the top centre-left, peeking through the red block, their delicacy and recognisable form contrasting the scrunched up oil stick packaging dotted around the rest of the piece.

While researching this piece and Oscar’s approach I was really drawn to the comparisons he makes between his creative processes and that of cooking or fermentation. He’s stated that ‘Like a ramen broth: the richer it is, the better the ramen will be.’ And has also compared the process to that of ageing good wine or cooking a stew. These analogies bring to mind the nourishing qualities of both food and art. It also brings up the significance of food in the global South which is where both mine and Oscar’s family heritage lies. Gathering around food is always a celebration.

So now I’m interested to turn it around a bit and ask you: What do you feel or see when you look at this piece?

Oscar is a practising artist, currently represented by David Zwirner gallery. From 20 July to 26 August 2024 Oscar’s new commission The Flooded Garden will be on display in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. Visitors are invited to participate in a large-scale collaborative painting over the month, so make sure to check it out!

Here I share my reflections on this piece alongside an overview of Murillo’s process and practice. Field recordings and electronic sounds have been paired with my words in order to create an acoustic environment, within which we can view the piece anew. It was originally written and presented during Black History Month at Tate in 2023.

Present Tense

Mona Hatoum

Present Tense (1996)

Tate

“The regime that emerged from the 1993 Oslo Accords had the effect of denying Palestinian self-determination, while allowing the expansion of colonial settlement and occupation. The occupation is far more entrenched today than when we went to Madrid in 1991. Settlements have expanded… The settler population has tripled during the so-called peace process. This ‘peace’ process in effect constituted another phase in the American-Israeli campaign against the Palestinians, its primary aim continuing to this day is to bring the Palestinians to accept their defeat in the long war that has been waged against them since 1917.”

- Rashid Khalidi The Hundred Year War in Palestine SOAS University of London

“Distance carries in its essence so many things, and the question is, is distance measured by kilometres, imposing apartness and determining longing, the greater the distance the greater the pain.. And less if the distance is shorter?

“Israel and the United States divided and subdivided ever-diminishing bits of Palestinian territories into smaller and less viable units for the unfortunate Palestinian authority to take over and misrule, all under the misleading - not to say willfully deceptive rubric of the "peace process."

- Souha Bechara, Untitled Part 1: Everything and Nothing(Translated from Arabic)

Was there ever any other intention at any time? I don’t think so. It wasn’t peace that they wanted, but pacification for a time. The Oslo accords were far too much of a whole with several prior decades of Palestinian dispossession, house demolitions, land expropriation and attacks on civil society. As against that, a moral and political solidarity building up between Palestinians all over the world-some of it was evident in the past weeks’ worldwide protests.”

- Edward Said at Ewart Hall, The American University at Cairo [2003]

Or the more I am close to the unjust, the more painful it feels? And the farther I am from injustice the less I suffer? If distance was essential for me and determined my feelings and decisions, we could not have continued on the road of resistance, which is a very difficult road.”

- Souha Bechara, Untitled Part 1: Everything and Nothing(Translated from Arabic)

“The great historian and theoretician of Colonialism, Patrick Wolfe, who sadly just passed away said the following: And I am quoting Patrick Wolfe:

‘Settler colonies were (are) premised on the elimination of the Native societies. The split tensing ‘where / are’ the split tensing reflects a determinant feature of settler colonisation. The colonisers come to stay. Invasion is a structure not an event.’

Rashid Khalidi The Hundred Year War in Palestine SOAS University of London

“Liberation of the land is the priority. And then continuing in political, economic, social, and cultural struggle. We have no boundaries, our boundaries should be the love that continues forward. If we want to define that movement, it goes beyond acceptance, beyond tolerance, it is the capacity to reach an empathy with the other, in a way that encompasses everyone. Democratically, with liberty, equality, and justice. And it’s the creation and maintaining of a system that asserts itself without attacking and without assaulting the other on a daily basis.”

Souha Bechara, Untitled Part 1: Everything and Nothing (In Arabic)

Sounds of Palestinian artisans making traditional soap by Handmade Palestine are woven between protest songs I recorded in London. These are heard alongside resources discussing the interconnected histories of Palestine, Lebanon, Israel and the UK sourced from Radio Alhara and Learning Palestine.

Excerpts include a 2001 interview with Soha Bechara by Jayce Salloum, a 2003 lecture by Edward Said at The American University at Cairo, and a 2016 lecture by Rashid Khalidi at SOAS University of London. An English translation of Soha’s words are included in the transcript (originally spoken in Arabic).

The Cost of the English Landscape

Ingrid Pollard MBE

The Cost of the English Landscape (1989)

Tate

Even the title of this work, The Cost of the English Landscape, and it’s like, what costs are being paid to uphold this [landscape]? And it’s even the same with like, even digital images, and every time we send an email - that’s having an impact and we don’t… We’re not encouraged to think about it basically, you know, so it’s very easily ignored.

And everything we do is being upheld, unfortunately, very often by people who are suffering in order to make these systems run. And how that is kind of excluded from our everyday - and that is [excluded from] images we consume if it’s Instagram, if it’s the news, if it’s shiny advertisements and they don’t show you, like, where these things come from and what’s actually involved.

And Ingrid’s work, she’s talking actually a lot about the nuclear sites that are built in the English landscape.

The Ministry of Defence are one of the largest landowners in the UK, so when you think about this beautiful English landscape and people’s access to the outdoors, realistically a very large proportion of that landscape is used by the army to train in violence so they can then impose that violence on other people in other geographies, and you know about the cost of war on a geographical and a climate level.

‘Throughout England there is a map being made, a map of the land and its people; it is large and is added to every day. This image map, this photographic collage of the country, makes and remakes our sense of place, puts us into place, delivers a sense of place and sometimes makes us feel out of place. This map which locates and dislocates us cannot be escaped. We are forever inside the image of the land, its culture and its naturalness.’

- The cost of the English landscape : new photography by David A. Bailey, David Fox & Tony Roberts, John Fraser, Ingrid Pollard.

It’s kind of how your outlook is like: are we asking permission to be in these spaces and to be accepted into these spaces? Or are we knowing that… Yeah. Asking or taking?

The idea of incorporating the Black figure within this landscape is, it is an omission of belonging, and that… It shouldn’t be juxtaposed and it shouldn’t be political but it kind of is, because it’s not something that we’re allowed to, um, have that connotation [that we do belong].

It’s the central figure of going over the border there, you are on public land so you are meant to feel like you can be there, but it’s how other people perceive you. What are you as a Black person doing outside of London, in the middle of nowhere, when you’re literally just frollicking trying to be at peace, trying to enjoy the landscape the way everyone else does.

Even like looking at the way, I think it’s Ingrid who’s stepping over this fence, um, but like the way that she’s been split apart and, actually there’s these really big bold texts ‘KEEP OUT’, ‘NO TRESPASS’, ‘PRIVATE PROPERTY’... And I think… I love being outdoors and in nature as well but there’s this feeling of disembodiment sometimes, of actually not feeling like I fully belong there.

‘In the age of the image we have to redefine imagination, to photograph blackness where the dominant colour is white, to photograph the North when the dominant space is South, to photograph idleness when the dominant practice is work, to photograph the pastoral when the dominant language is technical. All these practices find themselves caught in a communication system not of their own making.

It is therefore the task of the photographer to discover new ways of telling and showing, of marking space through new procedures.’

- The cost of the English landscape : new photography by David A. Bailey, David Fox & Tony Roberts, John Fraser, Ingrid Pollard.

Exploring the place of Black and queer folk within the English landscape, I hosted a reading group with PRIM. We discussed themes of geography, mapping, exclusion, art, photography and race relations in the UK among others, drawing on resources from Tate and iniva’s libraries and archives. Excerpts of the readings and discussions are combined here with sounds of the countryside which I recorded in London (Epping Forest and Hackney Marshes) and the ancient woodlands of Dodford, Worcestershire.

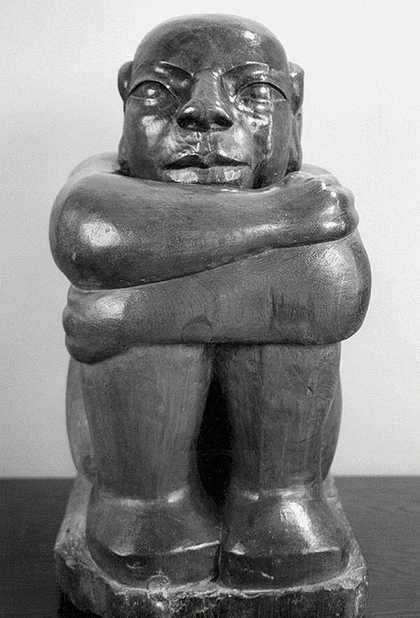

Ronald Moody

Ronald Moody The Onlooker 1958 teak, 65 x 32 x 38 cm

© the artist's estate

ALL EMPIRES, AS ALL THINGS MUST, WILL EVENTUALLY ROT AND DECAY.

Chapter 1:

Year 1500, Norman England

It’s 1500, Norman England, Feudal rule. The great council has recently been replaced by the Parliament of England leading to greater civil liberties. If you’re male, over 21 and own land you have the chance to influence the decisions in the country via a vote.

If you’re not, you don’t. It won’t be until 1774 that Ignatius Sancho votes in Britain - the first known British African to have done so.

Standing where we are right now, we’re surrounded by water. You’re wading through it.

For the Thames is much wider than you might be used to. So much shallower too.

You’re in Westmynstre, just under 2 miles away from London - the newly established capital of England whose city wall stretches just beside St Pauls Cathedral. Westminster will be absorbed into the city in around 1786.

You’re surrounded by marsh land. It’s infested with mosquitos, you hear them, don’t you? Between the sway of reed and gentle flow of the river between the Flood Plains.

4,000 miles away the Caribbean has recently been claimed by Columbus and is soon to be irreparably damaged by European colonialism and the plantation system being established. Fellow inmates from this very spot will be sold into the system of webs connecting Africa, The Caribbean, Australia and the United Kingdom. The very systems which funded the building of the Tate Britain galleries.

Chapter 2

Year 1651, Stuart England

It’s 1651 Stuart England and the smell of boiling bones fills the air as the production of glue is heavy under-way. You’re surrounded by the walls of Tothill Fields Bridewell Penitentiary. A space for those criminally inclined. The population of the prison has drastically swelled as 4,000 defeated Royalists are being temporarily imprisoned - held here - ahead of their being sold into a system of enslavement and trafficking. Sold to merchants trading in Africa and the West Indies.

The land you’re standing on, claimed from the flowing river maintains a current. Continued to be a place in motion. No longer a natural, gentle flow. Violently expelled and without mercy for some. For others, inhumanely kept and degraded. A final destination, no escape but dying.

Forced migration, trafficking, enslavement

What’s the worth of a human body? To toil?

Reduced to a provider of physical labour for the profits of a few.

The first full society of enslaved people was a recent English infliction on the island of Barbados, though chattel slavery has been established for nearly 20 years, and the enslavement of Africans on Sugar plantations has been enforced for over 100... The population of an entire continent regarded as no more than providers of labour, produce and wealth for Europe.

Over and beyond this period systems and structures of extraction and racialised prejudice are being implanted and engrained through many mediums. Art and visual representations of British colonies included.

4,000 miles away. Sugar plantation. Sweet sticky air. Blood sweat and tears.

Blood sweat and tears here, too. We see the bodies dropping.

Diseased and dying.

Chapter 3:

Year 1869, Victorian England:

It’s 1860, Victorian England. You’re now in London, as Westminster has been recently absorbed into the city.

Around 200 miles away Henry Tate, founder of the Tate Gallery, has gone into partnership with John Wright, a sugar refiner based on Manesty Lane, Liverpool. It will be another 20 years until the London-based Silvertown refinery opens. But profits are beginning to be made off the backs of formerly enslaved Caribbeans which later leads to the acquisition of this very land.

But you are here. Millbank Prison has been built around you. A failed Panopticon. A failed model prison. Having replaced Tothill Fields Bridewell Penitentiary and establishing itself as the largest prison in Europe. Deemed unfit for holding prisoners long-term due to its state of degradation. A state of Limbo. You’d have spent around 3 months here before being exiled to Australia along with tens of thousands other convicts over the years. The next stage would be transportation via the dreaded prison ships. Getting off lightly when compared to the sentence of death by hanging, or possibly not..

You could be here for many reasons, most likely theft of some kind. Crime produced a constant stream of free labour for Britain to expand and build its colonies. Since the Slave Trade act was introduced in 1807 and the Slave Abolotion Act in 1833 these streams needed to be maintained somehow. And who knows, after serving your sentence in Australia you may end up becoming quite the successful settler. A life better off, perhaps, than the city Slums of England.

Chapter 4:

Year 1948, Post-War England

It’s 1948 post-war Britain. You’re now standing in the newly renamed Tate Gallery.

Formerly the National Gallery Millbank and the National Gallery of British Art before that.

The gallery is preparing for an upcoming exhibition titled Contemporary South African Paintings, Drawings And Sculpture which will open in September this year.

The city of London’s population has been overtaken by New York, with many people leaving the city in search of greener spaces. At the same time, the British Nationality Act was passed, granting citizenship to the colonies. Not far down the Thames, in Tilbury, the Empire Windrush has docked, carrying one of the first large groups of post-war Caribbean folk, later to be known as the Windrush Generation.

This is the beginning of an influx of emigration from the Caribbean of people who would start to fulfil the role of workers needed to help with the post-war reconstruction of Britain.

The gallery has survived a major flood and two World Wars since its opening in 1897. The room you’re in is part of the original building containing just 8 rooms and 245 pictures, before being extended drastically to over double its original size. The environment around you is now much more familiar to what you might be used to. And extremely far from what it had been just 100 years earlier.

But to what extent is there, in fact, an overlap? Not in extremity of deprivation, but in intent. To time travel a bit and quote Shimrit Lee’s Decolonise Museums:

“The museum was considered an instrument towards such ends--a space of learning and personal growth for the working class that could counteract "the corrupt influences of the saloon and the race-track," as Boas put it. In this way, the museum served a similar function as the prison. Both were holding spaces-of objects and bodies, respectively-as much as they were highly surveilled institutions that promised personal salvation and rehabilitation.”

Perhaps this site holds fragments of its memories, unable to fully shake off its history?

Chapter 5:

Today

You’re back in 2024, but it’s not quite the same as it was... You’re no longer the same.

I invite you to look around again with new eyes and a new understanding. Can you see what I have seen? Unearthed place memories haunt these walls, the ground beneath our feet.

As with the majority of haunted places, Millbank is a place that has, in many ways, become somehow infected by what has happened within it.

The Onlooker guides you through the history of Tate Britain and the site it stands on. Plantations and colonisation in the Caribbean are connected with the historical marshland swamp, Millbank prison complex and finally Tate Britain gallery. Supernatural encounters and sonic reverberations merge past, present and future.

Repose on the Flight into Egypt

Glyn Warren Philpot

Repose on the Flight into Egypt (1922)

Tate

Divine triad, nuclear family … Welcome to Kemet - the Black Land…

The sand whispered the travelling family into existence. Through their tracks and trails, lifted up and carried through the wind. Joining a legacy of traces and displacements.

Land gently fades into water, along the bank of the Nile stretching from Lower to Upper Egypt.

Subtle, weighed against the vastness of the desert, the vastness of time past, present and future. But every detail, every grain of sand, just as important as the next…

WOMAN OF STONE:

My love, when are we again?

SPHYNX:

The family passes through.

Mother, father, child king…

WOMAN OF STONE:

Em Hotep,

Isis, Horus, Osiris. (overlapping)

SPHYNX:

Our Black Land, their Refuge

CENTAUR 1:

How many have passed,

How many more to come?

JINN 1:

How many Lifetimes?

JINN 3:

How many massacres?

JINN 2:

How many Revolutions?

JINN 3:

How many revolutions will it take?

SPHYNX:

Yes, oh, yes

Things shift.

CENTAUR 2+3:

We followed them down since Rafah, protecting them along the way.

SPHYNX:

Oh, how things shift.

There will come a day when even the swell of the banks are a distant memory.

High Damn, Low Damn, Aswan, Nubia.

Freedom of movement restricted by governance.

WOMAN OF STONE:

Even this, as all absolutes must, will dissolve…

CENTAUR 1:

We see the shifts,

Binaries introduced and reinforced,

This human species increasingly restricts themselves.

Even their categorisation of desire.

Why should pleasure have limits?

JINN 2:

If they allowed themselves to be themselves, and others to be others, their world would be a beautiful place.

JINN 3:

Not without its discontents

SPHYNX:

Individuality and society will be united.

I have seen it on a distant horizon.

JINN 1:

The seed is planted.

CENTAUR 1:

Just as the cactus blooms, every seed containing a world which will be recalled. When the environment allows.

WOMAN OF STONE:

The constant shift. Cyclical. Forever expanding, contracting.

Before your life times I have seen it too. Before desert - oasis.

Desertification before and because of them.

But back to that oasis we all return.

Even this body, my body, will be sand once more...

SPHYNX:

ad aequilibrium

An immense coil, each new beginning closer to its end than the last.

Through this piece I could connect with Ancient Egypt and related African histories, traditions and myths which were later adopted, replaced and retold through the Greek and Roman empires. These stories and their characters have been fetishised and white-washed which is something I want to interrupt with this new reading.

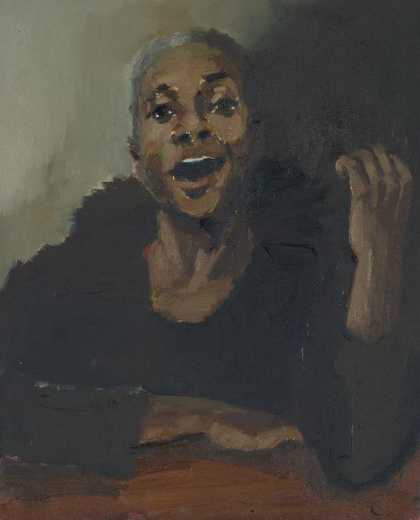

Razorbill

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Razorbill (2020)

Tate

With this piece I wanted to expand on the possible context the sitter exists within. What might she be saying? What sounds could surround her? Bringing together a collection of sound clips by Lie Ning, Tereza Delzz, Tawiah, Tia Simon-Campbell (Sippin’ T) and myself, we each offer a voice to the central figure in the painting.