Fig.1

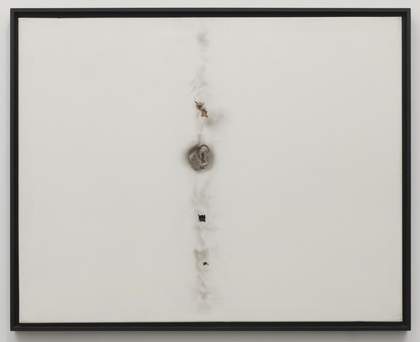

Henk Peeters

59–14 1959

Oil, burn holes and plaster on perforated canvas

455 x 450 mm

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

© Estate of Henk Peeters

Fig.2

Henk Peeters

Burn Hole 1961

Plastic and wood

800 x 1010 mm

Tate T13407

© Estate of Henk Peeters

At first Peeters’s ‘pyrographies’ (fire drawings), were made from burning holes into stretched canvas (fig.1). All-natural fabrics, such as the cotton from which artists’ canvas is made, have a distinct texture, derived from the way the fibres are woven together, and they will also have minor imperfections, such as loose threads or little knots. These very small inconsistencies can be obscured under layers of size and primer, which once dry can be sanded or smoothed before paint is applied, but a ‘tooth’ on the canvas surface will usually remain and is very useful for drawing paint from a brush. It served little purpose for the hands-off practice of burning, though. Conventional artists’ canvas, known as cotton duck (from the Dutch doek, meaning linen), also varies enormously in colour and can in fact be very brown. Bleached cotton varieties are available in quite bright shades but will always have a natural tinge. The plastic used for Burn Hole 1961 (Tate T13407; fig.2) had no such problems of textural unevenness and it also came with its colour already embedded in the material. As is examined in detail in Carla Flack and Emma Richardson’s contribution to this publication, the greater variety of ways that PVC responds to an extreme heat source will also have made it attractive to Peeters.1 Furthermore, just as Burn Hole represents Peeters’s transition from abstraction to reality, as is shown elsewhere in this In Focus, so its material potentialities encompass concepts of immateriality that were extremely current elsewhere in avant-garde practice of the time.2

As an example of the interconnection of material and immaterial qualities in Burn Hole, we can consider the work’s whiteness, which relates to the kind of effects Peeters described in a letter sent to the artist and architect Charles Karsten in January 1961, around the time that the work was made. Karsten was the secretary of an artists’ collective called the Liga Nieuw Beelden (New Images League), which had an annual exhibition in the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Peeters pitched him an idea for an exhibition, titled Nieuwe Konseptie (New Concept), explaining that it would give an overview of ‘contemporary movements in painting and sculpture, which are identified by the names of “informel” or “monochrome” art and which are characterised by the endeavour to supersede contrasts, colour effects and composition, and thereby attempt to give form to silence, emptiness, space or the sense of scarcely breathing.’3 The exhibition was to have included some forerunners in the form of art informel, tachisme and expressionism, ‘in so far as they incline to simplification, silence and emptiness.’4 White plastic, the colour of which is entirely consistent and which has no variations in texture, certainly cut down the amount of ‘noise’ that had still existed on the surfaces of Peeters’s informel paintings, no matter how ‘silent’ in terms of content they otherwise seemed to be.

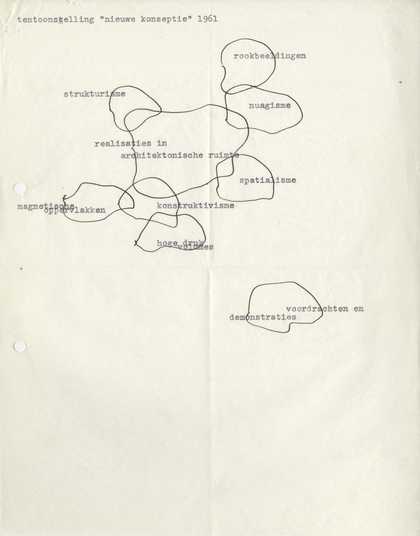

Fig.3

Henk Peeters

Diagram of the exhibition Nieuwe Konseptie, 1961

Henk Peeters Archive, Netherlands Institute for Art History, The Hague

© Estate of Henk Peeters

In his exhibition proposal for Karsten, Peeters also included a diagram that could be read either as a concept for the physical layout of the exhibition or as an explanation of the ways in which the various tendencies represented in it related to each other conceptually (fig.3). Like a wobbly Venn diagram, Peeters sketched it in a manner that has a powerful visual connection to Burn Hole, as a series of indistinct bubbles, clouds or perhaps even holes that overlap and circulate around each other. In some of them Peeters wrote the names of more familiar artistic movements, such as ‘constructivism’, which he presented alongside less well known or even completely fabricated ones, such as ‘spatialism’ and ‘magnetic surfaces’. Drifting off in the top right, as if into space, Peeters drew bubbles representing ‘nuageism’ (cloudism) and ‘smoke pictures’. As is the case with all the ‘sets’, the latter two terms represent something substantial (the works of artists to be shown in the exhibition) but do so in a completely indistinct way.

Again, the reference to ‘smoke pictures’ is another reminder of the importance that smoke played in Peeters’s pyrographies. It was not simply a by-product of the act of burning. The ethereal, wispy presence of smoke on the surface of a work such as Burn Hole does much to connect the kind of concerns Peeters expressed to Karsten – with emptiness, silence and space – to the material condition and object qualities of the work itself. In this regard, it is worth noting that the Dutch word for ‘material’, stof, has numerous meanings. On the one hand, it is used for things that are very concrete, such as ‘matter’ and ‘fabric’, akin to the English word ‘stuff’ but, on the other, also refers to that which is much less substantial, such as ‘dust’ and ‘powder’. The particles of ash that sully the pure white surface of Burn Hole are a physical, material residue but at the same time seem elusive as shadows to the eye.

The title of Peeters’s exhibition proposal, Nieuwe Konseptie, was in fact a Dutch translation of the subtitle of a previous exhibition, Monochrome Malerei (Monochrome Painting), which had been held at the Städtisches Museum in Leverkusen in the spring of 1960. Peeters effectively wanted to restage it in Amsterdam.5 Although he had not made it to Leverkusen in time to see the show, Peeters had been allowed to look at the works in storage. They included some of the first cut canvases by the Italian artist, Lucio Fontana, who had gone a step further than the perforated works that he had been producing for around a decade and which he exhibited en masse at the Venice Biennale in 1958, where Peeters saw them in the flesh for the first time. In place of the previously patterned arrangements of perforations, Fontana was now slicing open his bare canvases in brutal gashes. Fellow Italian artist, Piero Manzoni, was also represented in Monochrome Malerei by some of his ‘achromes’, all white works that emphasised their mute materiality. Peeters was already aware of these works, as Manzoni had shown similar ones in the Netherlands as early as 1958, at the Rotterdam Kunstkring, and had taken part in a Nul exhibition with two of Peeters’s Informel Groep colleagues that travelled from Rotterdam to Rome.6

Most controversially, Monochrome Malerei had also included four works by the French artist Yves Klein, who had first shown eleven all-blue paintings of identical dimensions at the Galleria Apollinaire in Milan in January 1957. Klein not only objected to being exhibited alongside the other artists as an equal, rather than as the originator of the monochrome; he laid claim to the very word itself.7 He made a formal complaint to the museum’s director and also organised for letters to be sent to the local mayor, demanding that his works be removed from the exhibition and that his name be disassociated from it. Given that one of his contributions was a Zone of Pictorial Immaterial Sensibility, an invisible work, the only physical trace of which was the receipt a buyer would receive, this seems a rather ironic position to take.

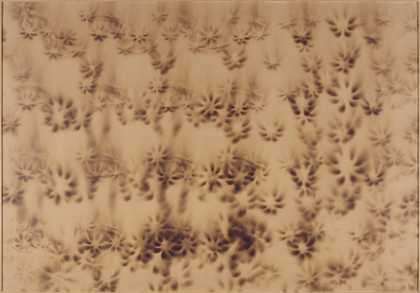

Fig.4

Yves Klein

Untitled ‘Fire Painting’ from the ‘fire wall’ at the exhibition Yves Klein: Monochrome und Feuer, Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, 1961

Charred paper on board

685 x 995 mm

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Klein was deadly serious, though, and reiterated his objections to Monochrome Malerei in correspondence with Peeters in July 1960, which he signed as ‘Yves Klein Le Monochrome’.8 Such claims for priority and exclusivity ran counter to Peeters’s worldview, which, as noted earlier, was rooted in left-wing politics and in ideas of collectivism. Around the very same moment that Peeters began his pyrographies, Klein also started conceiving works that involved fire.9 These first took the form of fire fountains and fire walls, such as were realised on a major scale at the exhibition Yves Klein: Monochrome und Feuer (Yves Klein: Monochrome and Fire) at the Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld in January 1961. Here a ‘fire wall’, made up of fifty Bunsen burners arranged in a grid, was used to create a series of ‘Fire Paintings’; large sheets of paper mounted on board were brought into close proximity with the burners, which left petal-like scorch marks all over them (fig.4). Although their correspondence carried on in friendly terms through 1961, Klein was to object vehemently to the formation of Nul and forbade Peeters to use either his name or any of his works – ‘material or immaterial’ – in connection to it.10

While it seems that, on the face of it, Peeters and Klein were treading very similar ground, Burn Hole cannot be mistaken for a work by the French artist and Peeters did not share Klein’s attraction to mysticism and oriental philosophy. Monochrome Malerei originally included one of the ‘monogold’ works that Klein began producing in 1959, a monochrome with an all-gold surface. Klein saw these works as connected to the ancient practice of alchemy (the search to turn base matter into gold) and to the golden Buddha figures he had seen in Japan.11 In many of his public statements Klein echoed the concern with ‘reality’ that Peeters would also regularly espouse, but the routes he chose to access it tended towards the transcendence of the here and now.12 The connection between the sensuous blue monochromes of Klein and celestial space, for example, is quite different to the prosaic qualities of Peeters’s white plastic. In 1965 Peeters stated unequivocally that ‘my work is something like 2% op-art and even that is too much for me.’13 It was not that Peeters had little interest in stimulating the senses, only that appealing to vision exclusively was contrary to his mission. It is worth recalling his route to the monochrome through informel painting where issues of tactility remained very important. This is yet another way to consider the materiality of Burn Hole; it exchanged the distanced and insubstantial world of the visual for something much closer to hand.