Edward Onslow Ford (1852–1901) was born in London but trained as a painter at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp and then at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich where his tutor encouraged him to take up sculpture. On his return to England in 1875, Ford began making sculptures of various sizes and in a diverse array of materials, producing an eclectic body of work that included furniture, imperial monuments, portrait statues (including ones of Queen Victoria and the statesman Gladstone), portrait busts (notably of his fellow artists) and decorative objects incorporating precious metals and stones.

A successful and influential sculptor, Ford’s works were sold to clients across the world. He was also much liked by his fellow artists. His friend John McLure Hamilton described him as ‘gentle and amiable … born to enjoy much and to suffer much’, as well as someone devoted both to family life and to art.1 Today, however, Ford is perhaps best known as the sculptor of a number of statuettes depicting adolescent girls. In the late 1880s and early 1890s Ford worked on two such pieces that, although not made at the same time, can be seen to be closely related, in part because of their references to ancient Egypt. First shown at the Royal Academy, London, in 1889, The Singer (fig.1) depicts a young nude female harpist performing a song, while Applause (fig.2), made and exhibited in the Royal Academy’s summer show in 1893, depicts a similarly nude girl clapping, perhaps accompanying a dance or a song.

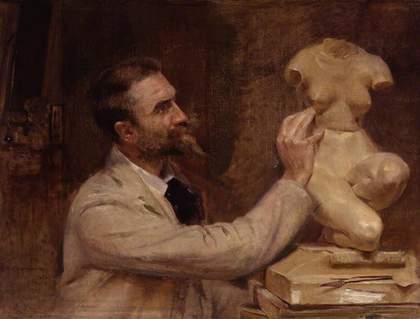

Fig.3

John McLure Hamilton

Edward Onslow Ford 1893

NPG 1866

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The neo-Egyptian iconography of the statuettes, not to mention their hieroglyphic inscriptions, indicate that Ford must have researched ancient Egyptian imagery and consulted experienced Egyptologists before employing life models to pose in his studio, from which the statuettes were modelled in clay. Studio assistants would then have cast the clay models in plaster, which Ford would have touched up using a range of small tools in order to sharpen up the details and textures of the statuettes. (The 1893 portrait by John McLure Hamilton shows the artist working on Applause before its head and arms were added; fig.3). The finalised plaster casts would then have been sent to a foundry (possibly either in Frome in Somerset or in Thames Ditton in Surrey, the most popular British foundries for sculptors of Ford’s generation), where the statuettes were cast in bronze before being returned to Ford’s studio. Here he added coloured resin paste, silver, turquoise, garnets and other semi-precious stones to the statuettes’ pedestals and accessories. Given their small scale, The Singer and Applause were evidently intended for domestic interiors of the wealthy upper and middle classes, rather than for grand halls in aristocratic country houses.

At the Royal Academy both works caused a sensation. The Singer was described in 1889 as having a ‘beautifully-modelled body’,2 to be ‘full of charm’,3 and ‘full of grace and exquisite finish of detail’,4 while one critic commended the way it combined sculpture and ‘orfèvrerie’, or precious metalwork.5 In 1893 similar praise was heaped upon Applause, which was described as the ‘most graceful – one might almost say most Grecian – piece of sculpture’ on display at the Royal Academy that year.6 Praise was given for the figure’s ‘spontaneity of movement and perfect modelling’,7 while another critic lauded the ‘graceful and sustained’ lines Ford employed, and drew attention to the way in which ‘song and music’ had ‘left their mark’ on the figure’s face.8

There was, however, some dissent. Writing about The Singer, one anonymous critic felt that Ford’s figures suggested ‘rather too strongly’ the influence of fellow Victorian sculptor Alfred Gilbert,9 while another thought that Ford had been too ‘faithful’ to his model, causing the figure’s legs to appear weak, her hips too high, and her throat ‘over muscular’.10 Criticism was also levelled at Applause, a piece commissioned by the mountaineer and collector Clinton Dent (1850–1912), for the way in which Ford had not ‘very thoroughly or searchingly modelled’ the figure.11

It is thought that the sugar merchant and philanthropist Sir Henry Tate (1819–1899) bought The Singer from the artist in 1894 with a view to including it in his gift of works to the planned National Gallery of British Art, which opened in 1897.12 (In 1932 the gallery was renamed the Tate Gallery in honour of its founder.) It is not known when but at some point in the object’s subsequent history The Singer was covered with a thick layer of dark beeswax. A likely explanation is that the original layer of oil on its surface had become mottled, and somebody thought it best to try to unify the appearance of the surface by adding the brown wax. This decision is undocumented because the Tate Gallery did not employ its own sculpture conservators until 1986; before then its sculptures were looked after by staff in other museums. They may have taken the decision to add the wax; alternatively, a Tate ‘maintenance team’ may have done so. Reflecting modern taste and an aversion to the late nineteenth-century fascination with colourful mixed-media works, the decision hid the true nature of The Singer for some decades.

Fig.4 The Singer exhibited 1889 (detail of front of plinth mid-restoration)

It was not until the early 1990s that, in the course of a research project, Tate conservator Pip Laurenson rediscovered and restored the sculpture’s colours (fig.4). Laurenson’s research also led her to find Applause in the collection of the descendents of its original owner and resulted in its later gift to Tate in 2008. As soon as the two works were compared, it became clear how closely related The Singer and Applause were, and why contemporaries had frequently described them as a pair. In her 1999 study of The Singer Laurenson concluded that Ford’s work should be repositioned within the ‘context of the highly decorative nineteenth century’.13 This In Focus aims to take up the challenge set by Laurenson’s research by examining this and other contexts for Ford’s works in greater detail.