Is Black Wall (Tate T00514) one sculpture made from many parts, or should each of its parts be understood as a sculpture in itself? By 1963 Nevelson could claim that the ‘single box’ was something that did not ‘interest’ her.1 But when Black Wall was made its combination of multiple boxes was still a relatively new innovation for the artist. This development might have even been the outcome of practical, rather than artistic considerations. As art historian Laurie Wilson has described, it was the logic of storage that appears to have initially prompted the artist to ‘stack and arrange the separate pieces as compositions just to make working space’.2 It is clear that Nevelson carefully arranged the contents of each box, but to what extent did she control the arrangement of the work as a whole? Such seemingly simple questions open up a complex field of enquiry concerning the history and identity of Black Wall. This chapter addresses such fundamental questions about its status as an art object, reconstructing its complex early history and changing form.

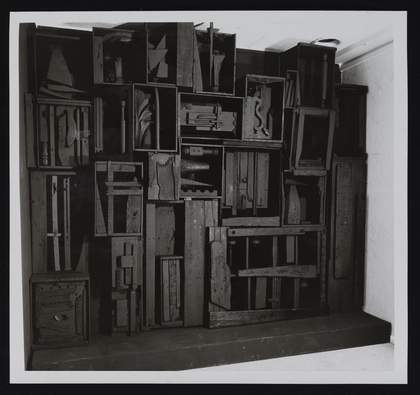

Fig.1

Louise Nevelson

Sky Cathedral 1958

Painted wood

3439 x 3054 x 457mm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Louise Nevelson

Before Nevelson’s grouped arrangements came to be fixed, a variety of sources suggest that their quantity and arrangement were inherently variable. ‘At least at the start’, as critic Hilton Kramer has described, Nevelson’s walls brought together ‘forms that had formerly existed as separate conceptions’.3 According to Wilson, it was only in the early 1960s that Nevelson began to ‘preserve the combination of boxes that made up the walls by screwing them together’.4 In line with the early date of Black Wall, the documentation that Tate received from Nevelson’s New York dealer specified that ‘units are never to be nailed together’, such that it remained possible that the form of the work could be modified.5 While Nevelson’s gallery asserted that ‘the units of a wall relate exactly to one another’, and even supplied photographs so that the installation of her work could ‘duplicate exactly the concept of the artist’, they also admitted that ‘re-arrangements are possible for the particular situations and places’.6 Period observers of her work equally understood the mutability of her forms; in the year Black Wall was made a writer for Art International described Nevelson’s walls as constructions of ‘interchangeable units or boxes which can be rearranged and extended indefinitely’.7

However, the unitary identity that the title Black Wall implies is supported by the suggestion in Tate’s cataloguing files that the work represents the ‘first wall she ever made’.8 It is a statement that serves to subsume the making of individual boxes within the totality of a single work. The original source for this claim appears to have been a representative from the London gallery from which the work was purchased, a source no doubt aware of the appeal of such origin stories for museums and art historians alike. But in her 1963 interview with the critic David Sylvester, discussed in the following chapter, Nevelson made an apparently similar but in fact rather different claim for Black Wall, describing it as the ‘first wall ever sold’.9 In 1969 Tate wrote to the artist herself to clarify the work’s status, and received the following response: ‘My black wall in Tate’s collection was indeed the first finished wall’.10

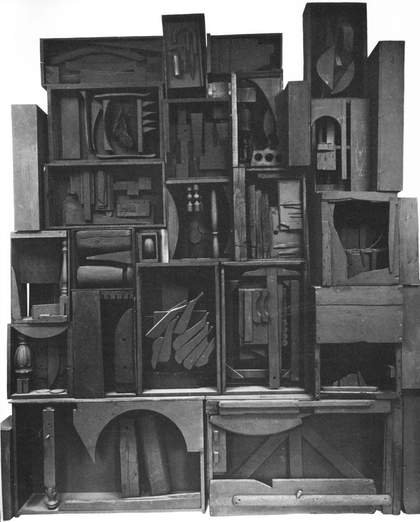

Further investigation problematises this claim. It is certainly contradicted by the many other Nevelson walls catalogued with earlier dates. In the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, for instance, Nevelson’s Sky Cathedral (fig.1) is dated 1958.11 This work was originally part of the installation of boxes that snaked around the walls of Grand Central Moderns for Nevelson’s exhibition Moon Garden Plus One, which opened in January 1958. Many other walls began life as part of this same installation. To understand Black Wall as a kind of first, it would have to be thought of as a unified sculpture, distinguished from earlier and otherwise similar looking works that originated from larger improvisational installations. The component parts of Black Wall would, in other words, need to be understood as integral elements of single composition with a fixed form.

When Tate pressed Nevelson to recall ‘whether the stacking of the boxes was an afterthought’, Nevelson’s response – or at least that which was typed on the letterhead of her gallery – veiled the making of Black Wall in the mystical cloak of creation:

I am compelled to tell you that I do not think in afterthoughts. I am cloaked in psychic phenomena so how can I answer your question. My creative life is creative energy plus physical energy; your question is primate and factual – a mathematical problem. I appreciate your concern but I cannot answer the question.12

Nevelson might have corroborated the originary status of Black Wall, but in dismissing further investigation into its making as a mere ‘mathematical problem’ she also avoided the more complicated questions that her claim raised. Are all of its boxes of the same date? Were they all made specifically for this wall? In the case of Black Wall, further research reveals that Nevelson had a good reason to avoid such questions, for the arrangement of the boxes changed several times in its early history, as did the precise number of boxes it contained. Several of its boxes had even been shown as part of an entirely different sculpture. This complex history defies expectations that modernist sculpture should maintain a stable, singular and unified form. For Nevelson, these complexities were to be subsumed within unexplainable ‘psychic phenomena’, repressing the innovative formal instability of her sculpture in favour of a more romantic image of the work as the realisation of her unique creative energy and personal vision.

Because the changing form of Black Wall echoed its transfer through the hands of several dealers in the years after its production, its history is also entangled with Nevelson’s escalating commercial success. By the time the work arrived at the Tate in July 1962, less than three years after its stated date of production, the sale of the work had drawn the involvement of four commercial galleries in three countries. The work was shown in a group exhibition at the Hanover Gallery in London from June until September 1961, where it was on consignment from the Paris-based Galerie Claude Bernard, whose director Bernard Haim had bought the work in early 1960 through Nevelson’s New York dealer Martha Jackson.13 Although the sale was invoiced through Jackson’s gallery, a letter from Jackson held in Tate’s files records that Haim ‘originally acquired this Wall directly from Mrs Nevelson’.14 A further note in Nevelson’s papers records that the work was ‘sold thru David Herbert’, indicating the involvement of another New York dealer (with whom Nevelson had also exhibited) in the negotiation of the sale.15

The work does not appear to have been shown publicly in New York before it was sent to Europe. In an inventory of Nevelson’s records, dated 6 January 1960, the wall slated for Haim was, at that point, located on the top floor of Nevelson’s new Spring Street studio.16 While the Haim sale was being finalised, Martha Jackson was simultaneously negotiating a sale of Nevelson’s work with competing Paris gallerist Daniel Cordier, who would go on to become the artist’s main European representative. A December 1959 letter from Jackson to Cordier disclosed the progress of the Haim sale: ‘We think you should know that Haim purchased two small walls from us, one for his own collection and one for his American show’.17 While it is not clear if Haim exhibited Black Wall at his gallery, or if he purchased a second wall, the first public showing of Black Wall in Europe appears to have been in an exhibition at the Musée d’Art et d’Industrie in Saint-Etienne, which opened in March 1960.18

Fig.2

Louise Nevelson

Black Wall 1959

As reproduced in Sculpture and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, Hanover Gallery, London, June–September 1961

© Louise Nevelson

Photo © Hanover Gallery

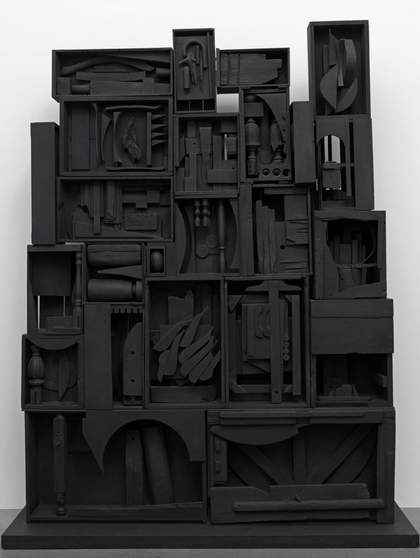

Fig.3 Louise Nevelson

Black Wall 1959

Tate T00514

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016

Just as the sculpture itself travelled internationally, so too did its photographs, making it difficult to correlate each image with a particular exhibition or location. What they reveal, however, is that in less than two years several different arrangements of the sculpture were photographed and reproduced. In the catalogue for Hanover’s 1961 exhibition, Black Wall was listed as having twenty-seven units, although the accompanying image appears to contain approximately thirty units, with additional outwards-facing boxes stacked on either side of the work (fig.2).19 Accounting for the variation between the catalogue image and the work as it came to be displayed at Tate (fig.3), Hanover Gallery explained that the photograph depicted an ‘earlier version’ of the work’.20 ‘The reproduction was from a photograph given to Mr Claude Bernard Haim bearing the stamp of David Herbert Gallery’, explained Hanover Gallery’s Erica Brausen in a 1964 letter, further confirming Herbert’s initial involvement in the sale of the work.21 Rebuffing the insinuation that a dealer might have siphoned off boxes for separate sales, Brausen emphasised that the reduction of the work to twenty-four units occurred before it was sent to Europe and was ‘according to Miss Nevelson[’s] own decision’.22

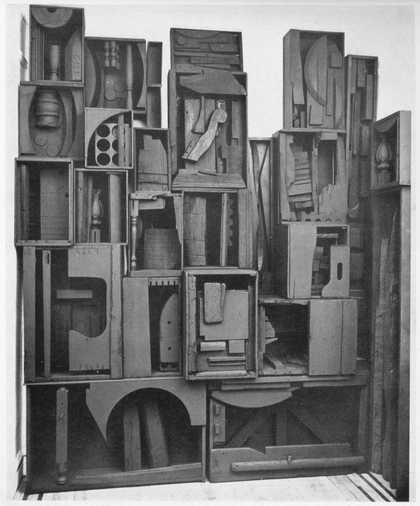

Fig.4

Louise Nevelson

Black Wall 1959

As reproduced in Cent Sculpteurs de Daumier a nos Jours: Catalogue par Maurice Allemand 1960, exhibition catalogue, Musée d’Art et Industrie, Saint-Etienne

Louise Nevelson papers. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

In fact, the shifting form of the work was even more complex than even this explanation revealed. The catalogue for the exhibition at the Musée d’Art et d’Industrie reproduced the work in a further variation (fig.4).23 This image is also held in the archives of the Hanover Gallery, and so probably shows the work as it was installed at one of these two venues.24 While the number of boxes in this image appears to match the number now held at Tate – corresponding with the shipping note that records twenty-four boxes being sent to France – they appear here in a wholly different arrangement.25 The box located just below the top left unit of the wall appears instead at the bottom of the composition, wedged between the two largest units of the sculpture. All of the other boxes appear in different positions and orientations. The composition is, as a result, wider and shorter than the current arrangement of the work, and the irregular stepped appearance of the left side of the sculpture provides a less orderly shape. While one reviewer of the Hanover show noted of Black Wall a ‘lack of distinction in its overall shape’, they also understood the work to comprise ‘a number of wooden units which can be assembled in various ways’.26 While Black Wall now appears as a sculpture of fixed arrangement, clearly at least some of its period viewers understood its design to be entirely more malleable.

The improvised arrangement of Nevelson’s sculptural units into expansive constructions posed problems for Nevelson’s dealers, according to Glimcher, as they were ‘not really compatible with the concept of collecting separate examples of an artist’s work’.27 The multi-part nature of her constructions made it difficult to keep track of the precise contents of each sculpture. In one instance, a dealer called Nevelson ‘with great excitement and anger’ to report that he had discovered ‘one piece of this sculpture that is missing’.28 ‘There was one piece of wood that I had taken off’, Nevelson admitted, explaining that she had made it ‘years before’ it was exhibited, such that ‘time had given me two versions of the piece’.29 But when a museum director wished to acquire ‘the first version’ of the work, Nevelson agreed that this was ‘justified, since it was dated at the time it was made’. The artist found the missing element in her studio and reattached it, allowing this unnamed New York museum to acquire the work.30

Fig.5

Louise Nevelson

Wall – Night Reflections c.1958, No longer extant

As reproduced in Art International, III, No. 3–4, 1959, p.49

© Louise Nevelson

Photo © Art International

Fig.6

Louise Nevelson

Sky Cathedral Variant 1959, Formerly known as Wall

As reproduced in Nevelson, exhibition catalogue, Martha Jackson Gallery, New York, 1961. Plate XI.

Louise Nevelson papers. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

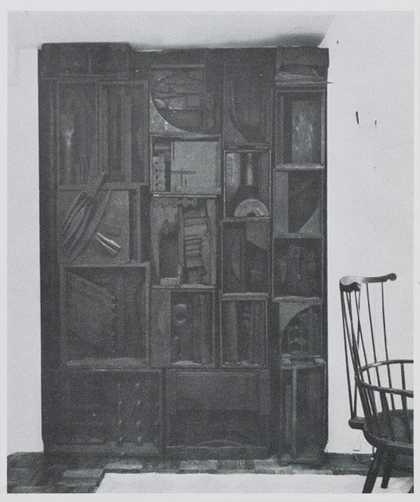

The unstable form of Black Wallis further complicated by an image of a related work reproduced in Art International in 1959 captioned ‘Wall – Night Reflections’ (fig.5). Close examination of this image reveals that several of the boxes from this work ended up in Black Wall. The two lowest boxes provide the same base for Tate’s wall, and at least four of the other boxes are common to both compositions. The half-covered box on the right-hand side of Tate’s work appears in this image on its side in the equivalent position. Many of the remaining boxes in this earlier arrangement can be traced to still other walls. Five boxes ended up in the wall owned by Jean and Howard Lipman, now known as Sky Cathedral Variant 1959 (fig.6), while another three boxes ended up in the large wall installed in the Rockland Hotel in Maine, operated by Nevelson’s brother – a sculpture now known as Sky Cathedral #2 1957 (fig.7) and held in the collection of the San Jose Museum of Art. In the catalogue of Nevelson’s 1961 exhibition at Martha Jackson Gallery, both of these related works are each listed with the more prosaic title Wall, suggesting that the title of Tate’s work originated from these earlier generic designations, perhaps appended by the gallery rather than the artist, rather than the more poetical titles Nevelson usually favoured.31

Fig.7

Louise Nevelson

Sky Cathedral #2 1957, Formerly known as Wall

Painted wood

3785 x 1448 x 406mm

San Jose Museum of Art

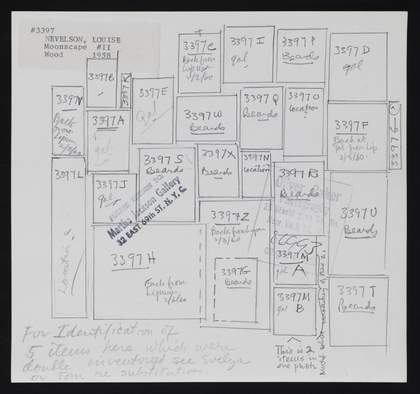

Black Wall was far from unique in being made from portions of pre-existing works. After it was awarded a prize at the Art USA 1959 exhibition, Moonscape II1958 (fig.8) was also disassembled and redistributed. A photograph of the work held in Nevelson’s archive is marked with a complex diagram on its reverse (fig.9), which indicates that most of its units ended up in the wall owned by New York collectors Lucille and Milton Beards. A note underneath the diagram acknowledges that several boxes were of unknown whereabouts, while others still were ‘double inventoried’. Further boxes are marked as being ‘Back from Lipman’, suggesting that in some instances boxes could be added and withdrawn from several walls.32

Fig.8

Louise Nevelson

Moonscape II 1958

Louise Nevelson papers. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Photo © Oliver Baker

Fig.9

Diagram of Moonscape II c.1960

Louise Nevelson papers. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Evidence suggests that Nevelson’s collectors exercised considerable autonomy in determining the precise arrangement of the works they purchased. Jean and Howard Lipman, for example, installed Sky Cathedral Variant in a niche, and it is possible that their work was composed to specifically fit this location in their house. To the same ends, collector Emily Tremaine told the artist that she had decided against separating the units of her small Nevelson construction, and instead asked for permission to add a small platform to her work to prevent it being ‘dwarfed’ by the architecture of her new Philip Johnson house.33 A 1962 letter from Martha Jackson concerning the Lipmans’ purchase records that their wall did indeed contain ‘one or two different boxes’ from its original form, requesting that Nevelson approve the final composition by ‘writing a note to that effect’ on the rear of a photograph.34

Black Wall was dispatched to Bernard Haim before a diagram or inventory could be completed, but records suggest that Nevelson’s dealer was still concerned to ensure that the full extent of the work was preserved.35 Haim had, according to a letter from Martha Jackson, ‘agreed not to break them up into separate sections for sale’.36 But as curator Brooke Kamin Rappaport has noted of Nevelson’s work of the late 1950s, the artist herself had a ‘propensity for disassembling and reassembling her sculpture’.37 And according to Laurie Wilson, some ‘collectors who owned more than one had been encouraged to move the boxes around at their discretion’.38 While Nevelson and her New York dealer took advantage of the formal (and commercial) flexibility availed by the modular format of the walls, they also wanted to avoid these works being deconstructed into single units. Despite this, the various versions of Black Wall that were exhibited, and its inclusion of boxes from an earlier work, makes it difficult to accept the sculpture as ‘the first’ example of Nevelson’s wall technique.

Nevelson saw Black Wall at Tate on several occasions after its acquisition. According to the minutes of the November 1963 meeting of the trustees, the artist had visited the gallery earlier that month to see the work, ‘which she also sprayed with a fresh coat of black paint.’39 When Erika Brausen from Hanover Gallery sought to clarify the variations of the work in a 1964 letter to Arnold Glimcher, Nevelson’s new representative at Pace Gallery, her letter sought to scupper ‘rumours … going round in New York that Louise Nevelson is very unhappy about the present state of Black Wall’.40 As Brausen noted, ‘Louise Nevelson was in London earlier this year’ when she ‘went down to the Tate Gallery twice to look at the wall and never mentioned anything to any of us at any time’.41 These visits were followed by the artist’s donation of An American Tribute to the British People 1960–4 (fig.10) to the Tate in 1965, an act that might appear to confirm the artist’s satisfaction with the state of Black Wall, or at least her disinclination to modify the work as it had come to be displayed at the museum.

Fig.10 Louise Nevelson

An American Tribute to the British People 1960–4

Painted wood

3110 x 4424 x 920mm

Tate T00796

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016

It is not entirely clear what arrangement of the work Nevelson would have seen when she visited Tate Gallery. It now appears that two further alterations were made to Black Wall after the work was photographed upon acquisition. Sometime between 1962 and 1965 the half-covered box near the lower-left corner was flipped, and the semi-circular unit with an arrow-shaped element was removed from the backboard of the lower right-hand box and reattached upside down. These differences become visible by comparing a current official view of the work (fig.3) with that taken in 1962 (fig.11). No documentation for either intervention exists, and through the process of this research project Tate conservation staff determined to leave both elements as they were rather than risk further damage to the work.

More broadly, the almost impossible to track histories of the individual units of Nevelson’s walls adds considerable complexity to the dating of the artist’s early constructions. Despite Tate’s wall being dated to 1959, based on inscriptions on the rear of two of its boxes, it has been shown that seven other boxes had already been included as part of Wall – Night Reflections, a work already reproduced in a magazine in 1959, and perhaps completed earlier than this date. Several other boxes from this earlier work ended up in Sky Cathedral #2 (fig.7), now dated 1957. Cataloguers of some other works have indicated the longer history of their component parts by providing date ranges: as an extreme example, Sky Cathedral Presence (fig.12) in the collection of the Walker Art Center is dated 1951–64.

Fig.12

Louise Nevelson

Sky Cathedral Presence 1951–64

Painted wood

3105 x 5080 x 606mm

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

© Louise Nevelson

This practice of combining and recombining boxes of differing dates continued throughout the 1960s, as exemplified by An American Tribute to the British People, which is now dated by Tate to 1960–4, but which arrived at the gallery with the date of 1965, despite containing boxes individually dated 1960, 1961 and 1962. Given how frequently Nevelson’s early walls were recomposed and recombined, efforts to seek an authentic composition or conclusive date of production for them are, at best, challenging. The artist’s own remark that Black Wall represented her ‘first wall’ belies the reality of her working practices at the end of the 1950s, the simultaneous production of many boxes destined for several different works, and the unstable form taken by many of her large-scale sculptural constructions.

In the 1960s Nevelson’s output relied increasingly on pre-fabricated boxes of a more consistent shape than those used in Black Wall. Eventually, as she began to collaborate with sculptural fabricators to make multiple editions and monumental outdoor sculptures, the more geometrical grids and industrial materials on which her work came to rely suggested equivalents between her work and the bland repetitions and architectural correlates of minimalist sculpture. ‘From the vantage point of the present,’ wrote Dorothy Gees Seckler in 1967, ‘we can see that almost a decade ago she had arrived at all the formal concepts that were to become important in the 1960s.’42 Elyse Speaks has shown how the spatial and temporal properties of Nevelson’s early environments also suggest their connections to minimalism.43 As the shifting material history of Black Wall suggests, Nevelson’s inherently modular constructions, seemingly able to be extended and recomposed at will, presents her art as an unwitting progenitor to the altogether more austere modular forms of mid-1960s sculpture.