The importance of themes in the visual arts has steeply declined in the last few decades, so much so that titles, which are given to abstract paintings and sculptures, often sound fake or pompous. Yet the narrative component is still important – even when it is subliminal or metaphorical like in music. Sometimes a title applied to a painting allows even the more objective viewer to ‘add’ something to the conceptual content of the work, to attribute metaphorical or allegorical meanings to that tangle of lines and colors, which otherwise would have ‘signifier’ without ‘signified’.

Gillo Dorfles1

Fig.1

Norman Lewis

Cathedral 1950

Oil on canvas

1168 x 635 mm

Tate L03741

© Estate of Norman W. Lewis; courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

In his review for the influential magazine Domus, Italian critic Gillo Dorfles praised the curator of the US pavilion of the 1956 Venice Biennale, Katharine Kuh. According to the critic, her thematic approach gave the show, entitled American Artists Paint the City, more coherence and unity than the other national pavilions that year. More importantly, the theme of the American city made American abstraction newly accessible. Dorfles mainly focused on the work of what he considered the most prominent artists in the exhibition: Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Mark Tobey, John Marin, Lyonel Feininger, Edward Hopper, Georgia O’Keeffe, Stuart Davis and Ben Shahn. He also mentioned some of the other notable names, which he identified as ‘more or less abstract painters’, but he failed to mention African American artist Norman Lewis.2

Dorfles’s silence on Lewis should not come as a surprise. With just one painting in a show including thirty-five artists and forty-six artworks, Lewis had little chance to leave a mark, especially because he was less well known than other artists in the exhibition, and Marin, Shahn, Hopper, de Kooning and Pollock had recently had major solo exhibitions in Italy. What is remarkable, in retrospect, is that Lewis did get noticed. Although he was not mentioned in Dorfles’s review, his 1950 painting Cathedral (Tate L03741; fig.1) was one of the few works to be reproduced and therefore widely seen in the pages of Domus.3 Why was Cathedral reproduced, and without accompanying comment? What did the painting stand for in the context of the 1956 Biennale?

This essay examines the pivotal yet under-studied role that the exhibition American Artists Paint the City had in the European reception of American abstract expressionism, and considers the significance of Lewis’s participation with his painting Cathedral. The exhibition received an overwhelmingly positive reception in Europe due to good timing – an openness at that time towards America and its art – and the effective curatorial approach of Kuh. Yet its role in the international success of American art has never been studied in depth. The only scholarly study is Mary Caroline Simpson’s 2007 article ‘American Artists Paint the City: Katharine Kuh, the 1956 Venice Biennale, and New York’s Place in the Cold War Art World’, which situates Kuh’s show within the American debate about abstract expressionism and its reception.4 Starting from Simpson’s solid analysis, my essay explores the European side of the dialogue and therefore understands the exhibition and its story as a two-way exchange.

As this essay will show, American Artists Paint the City aimed to make American art, and especially abstract expressionism, accessible and acceptable to the European public, and it largely succeeded in doing so. Lewis’s work played an important role in this, yet it also received superficial critical attention and fell into oblivion immediately after the show. Similarly, both American Artists Paint the City and Lewis’s painting were consistently excluded from the subsequent art historical literature on the promotion of abstract expressionism in Europe, which tended to identify the movement with a handful of (white, male) artists that came to represent the canon. By studying the circumstances and agenda behind Kuh’s exhibition and its reception, this essay has a twofold objective: to recognise the importance of Kuh and Lewis in the understanding and acceptance of abstract expressionism outside of the United States; and to gain a more nuanced comprehension of the crucial moment, immediately before the crystallisation of reductionist narratives surrounding abstraction, when diversity was a crucial value for the promotion of America and of American art internationally.

A precedent

Fig.2

Norman Lewis

Celestial Navigation 1952

Location unknown

Although Lewis had not exhibited in Europe before as other artists in Kuh’s show had, he was not completely new to that scene. The Italian art magazine Arti Visive had already discussed and reproduced his work in an influential essay: Ann Salzman’s ‘The Contemporary Non-Figurative Art Scene in America’ of 1954.5 This article had a key role in linking the art scenes of New York and Rome. It also provided the Italian public with the first overall mapping of and critical perspective on post-war abstract painting in the United States.6 An American art critic who travelled frequently between the two cities, Salzman facilitated exchange and reciprocal knowledge.7 Mapping post-war abstraction in the United States, she reproduced Lewis’s 1952 painting Celestial Navigation in black and white in her essay (fig.2) and grouped him together with William Baziotes, Mark Rothko, Theodoros Stamos and de Kooning. She called them ‘Expressionist Biomorphic’, describing their painting as ‘a shadowy and insubstantial world in which biomorphic objects hang in a state of suspension and uncertainty’.8 Salzman indicated two sources of inspiration, both of which were European: the German Blaue Reiter group and the Italian Metafisica artists. Avoiding references to major French movements such as cubism and surrealism was likely her way of seconding the Italians’ touchiness regarding the international prominence of the School of Paris. Salzman explained these artists’ Americanness through the ‘American obsession with science and industry’, and, more specifically, ‘the great emphasis in America on Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis’:

A struggle is evident between the forms (objects) and its [sic] environment which Stamos, Rothko, and Lewis conceive as a mysterious hazy atmosphere which seems to annihilate the form which is struggling within; an environment which seems to be the misty amorphous regions of our collective unconscious. Today the objective reality of the material world has receded. Mass has disappeared, become fields of energy. As science continues to delve into the mysterious regions of the atomic world, our world is becoming more and more obscure and abstract.9

Beside her Jungian references to the collective subconscious, which by the 1950s had become a commonplace mode of interpreting abstract expressionism, Salzman’s language reflected the dualism with which post-war American popular and intellectual culture approached the potentiality of the atom: anxiety and fascination, and emphasis on both its destructive and its creative power.10 In doing so, Salzman’s text introduced Lewis as one of the key protagonists through which Italian artists and critics accessed post-war American abstraction and its cultural context. But her essay came two years too early, and although it reached an influential group of artists and critics involved with Arti Visive, it failed to have the widespread impact that the same magazine had in 1956, when it discussed the work of Arshile Gorky and Pollock.11

Italy’s post-war Americanisation

Contrary to traditional accounts of the ‘triumph’ of abstract expressionism in Europe as immediate and inevitable almost at the inception of the movement, recent scholarship has shown that the Europeans, and especially the Italians, remained largely indifferent to the New York School until around 1956.12 Although visitors to the Venice Biennale had been exposed to abstract expressionist artists on a regular basis since 1948, when Peggy Guggenheim exhibited her collection in the Greek pavilion, it was in fact only during the second half of the 1950s that indifference and skepticism gave way to interest and acceptance.13 ‘American art has truly come of age’, wrote Italian critic Lionello Venturi in his catalogue text for Kuh’s show at the 1956 Biennale, and several reviewers echoed his judgment.14 Back home, Daniel Catton Rich, the director of the Art Institute of Chicago who served as the Commissioner for the Biennale’s international jury, triumphantly reported to the Associated Press: ‘Europe is imitating our paintings for the first time’.15

This change in attitude was in part due to a creeping disenchantment with communism and a growing interest in the American consumerist culture of the post-war boom. The combined effect of the 1956 Soviet Army’s invasion of Hungary and the end of McCarthyism in the United States from the mid-1950s corroded widespread anti-Americanism among Italy’s cultural elite, which had been largely affiliated to the Italian Communist Party.16 The overcoming of post-war hardship and the beginning of an economic boom led to a process of Americanisation of everyday life due to a new flood of imports of both goods and culture. As a consequence, an American economy of desire penetrated Italian society. It spread through both the industrialised cities of northern Italy and the rural areas of the south as an ideology or ethos before it changed actual behaviour, a phenomenon sociologists refer to as ‘anticipatory socialisation’.17 Italians, who in the 1950s were poorer than their Northern European counterparts, could not generally afford consumer goods. They nevertheless absorbed the culture and values associated with them. It was through American cinema, which was widely distributed and popular in Italy beginning immediately after the end of the war, that these goods and a new American-style consumer culture became accepted in Italy as synonymous with modernity. In a 1956 hit, popular musician Renato Carosone captured this new attitude. His song, ‘Tu vuo’ fa’ l’Americano’ (‘You Want to Act Like an American’) made fun of a young man from Napoli who affects American consumerist behaviours by dancing to rock and roll, wearing branded jeans and smoking Camel cigarettes, without having the money to afford this kind of lifestyle: ‘those cigarettes that you smoke leave mama broke’. Sung in popular movies by cinema stars Totó (1958) and Sophia Loren (1960), ‘Tu vuo’ fa’ l’Americano’ became the soundtrack of the economic boom.18

This wave of Americanism dovetailed with the ‘neo-Atlanticist’ foreign policy of Italy’s new political leader, Amintore Fanfani, who served as Prime Minister five times between 1954 and 1963.19 Italy’s physical and psychological reconstruction after the war had been characterised by Europeanism – the turn towards Europe as a frame of reference for the country’s new political and cultural identity. This was now superseded in the mid-1950s by the new rhetoric of a ‘bridge over the Atlantic’, which dominated Italian foreign politics and cultural diplomacy during the economic boom. Fanfani’s party, the Democrazia Cristiana, had formerly used the ‘communist menace’ as an argument to solicit political and economic support from the United States. Starting in the mid-1950s, this threat lost credibility and contractual power, and Fanfani adopted a new strategy.20 He presented Italy as a positive example of Americanisation. In particular, Fanfani saw the diplomatic crisis over the Middle East between France and Britain on the one hand and the US on the other, which culminated in the Suez Crisis of 1956, as an opportunity for Italy to become America’s privileged ally. He even proposed to the American president, Dwight D. Eisenhower (in office from 1953 to 1961), to use the recent reconstruction of Italy through the Marshall Plan as a successful model to ‘expand the area of prosperity’ throughout the Mediterranean.21 Italy presented itself as the preferential link between Europe and the United States.

The Venice Biennale followed a similar pattern of a change towards Americanism and an openness towards American art that was part of a larger opening up to the world. Art historian Nancy Jachec has documented how the Italian administrators of post-war Biennales had consistently focused on a cohesive Western European cultural identity and promoted gestural abstract painting as the lingua franca for achieving this. The 1956 edition, however, expanded its international boundaries far beyond Western Europe: the Soviet Union participated for the first time in twenty-two years; seven Asian countries joined in, as opposed to just one in the previous years;22 Argentina, Czechoslovakia, Egypt and Switzerland also exhibited for the first time.23 In this increasingly global landscape, Italy situated itself as the preferential cultural link between Europe and the United States in line with Fanfani’s Atlanticist rhetoric. While the French regarded the rise of New York as a menace to the centrality of Paris as the world’s cultural capital, the Italians, who had traditionally attributed the marginality of their own modern art in the international context to the monopoly exerted by the School of Paris, welcomed the rising power of the New York art scene as an opportunity for the international recognition of Italian art. As such, Lionello Venturi, a well-known and authoritative Italian art critic and a staunch supporter of artistic exchange across the Atlantic, wrote the foreword to the catalogue of the US pavilion. The same happened for the catalogue to the Italian pavilion, but in reverse: prominent Italian artist Afro Basaldella (known as Afro), whose work was included in the pavilion, obtained a text by Andrew C. Ritchie, the Director of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York. Ritchie had curated the US pavilion at the previous edition of the Biennale in 1954 and had organised The New Decade at MoMA in 1955, a show that gave Afro institutional recognition in the United States. Ritchie now presented Afro at the Biennale, where he received the top prize for Italian painting – that is, Afro’s first major recognition in his own country. It was the first time that an American critic had influenced the reception of a contemporary Italian artist in Italy.24 In the past, the Italians had merely considered America as a profitable market for their own art, but they were now becoming receptive to and influenced by American art, critics and institutions as well.

The Italians’ interest in transatlantic exchanges was reciprocated on the other side, as American artists, critics and galleries valued Italy, and especially the Venice Biennale, as an important entryway to Europe. US cultural diplomacy was changing too as the government started to embrace modern art as a means of promoting America and American values abroad. Only a few years before, in 1952, MoMA had had to publicly defend modern art from remarks by Congressman George Dondero, who deemed it communist and un-American.25 By 1956, however, the attitude had changed from hostility to support. Not only did MoMA purchase the US pavilion of the Biennale and establish the International Council (IC), whose aim was to tour exhibitions of modern art overseas, but the government finally recognised the importance of modern art to promote the American way of life abroad.26 In May 1955, as American Artists Paint the City came together, George Kennan, a former director of the State Department’s Policy Planning Committee and former Ambassador to the Soviet Union, urged MoMA’s IC to ‘show the outside world both that we have a cultural life’ and that ‘we care enough about it, in fact, to give it encouragement and support’.27 In other words, the Italians were open to American art like never before and the American government was supporting the exporting of modern art shows to Europe for the first time. What was needed now was a strategy to do that effectively.

Experiencing the city

Fig.3

Katharine Kuh with the organisers and sponsors of the 1956 American Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 1956

Left to right: Daniel Catton Rich, Arnold Maremont, Eileen Maremont, Piero Guadagnini, Italian Consul General and Kuh (seated)

Katharine Kuh Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., reel 267, frame 220

The 1956 Venice Biennale represented a turning point and an opportunity to redefine the way the European public perceived American art. Into this situation came Katharine Kuh, the curator of American Artists Paint the City. When MoMA invited the Art Institute of Chicago to organise the exhibition at the US pavilion, the trustees and Daniel Catton Rich, director of the Institute, immediately selected Kuh as the organiser of the show (fig.3).28 Recently appointed Curator of European Art and Sculpture at the museum (in 1954; she was the first woman to hold that position), Kuh was deemed the perfect candidate for the Biennale. As was emphasised in a press release that the Institute sent to Venice, Kuh had solid experience as a curator, having directed her eponymous gallery in Chicago from 1936 to 1942 and having worked at the Institute since 1943, where she organised an important exhibition of Louise and Walter Arensberg’s collection of modern art (1949) and a major Fernand Léger retrospective (1953), among other shows.29 If most of her previous efforts aimed at translating European art for an American audience, her job in Venice was to do the opposite: to bring American art to a European audience.

Even more than curating, the experience that prepared Kuh to do so was her lifelong engagement as an educator. The same news release stressed that since 1943 she had been in charge of the experimental Gallery of Art Interpretation of the Art Institute of Chicago, ‘where new methods in visual techniques are developed’. It also listed her successful didactic book Art Has Many Faces (1951) and her unpublished teaching manual Looking at Modern Art (1955). A former student of Alfred H. Barr Jr at Vassar College, Kuh shared his vocation as a missionary for modern art. In particular, she embraced the young Barr’s goal to make even the most esoteric forms of art relatable. ‘He never isolated art. He tied it up to everything – movies, design, industry, life’, she recalled.30 Kuh worked especially hard on her methods to persuade the public as to the relevance of the kind of art that she was presenting. As a Chicagoan and as a woman, she had to fight two battles: against the hostility towards modern art of a mostly conservative art world in Chicago; and against the indifference of a male-dominated and New York-centric modern art world.31 The methods she developed to do so proved especially useful at the Biennale.

Her strategy in Venice stood somewhere in between the emphasis on the general diversity and liveliness of the American art scene, which had characterised earlier Biennale exhibitions, and the more focused promotion of abstract expressionism that would characterise those of the late 1950s.32 This strategy was key in educating the European public about abstract expressionism and paving the way for its success in the following years. Not unlike Salzman, Kuh too gave prominence to Norman Lewis’s work, which was at the core of the mediating function of her show on many levels.

Through her curatorial choices in American Artists Paint the City, Kuh effectively capitalised on the newly favourable climate for American art. While her survey of a diversity of styles and generations was similar to previous exhibitions of American art at the Biennale, Kuh differed from her predecessors in her thematic approach. The theme of the city dictated the narrative of the show, which avoided traditional curatorial choices based on style or chronology.33 Artworks from different periods and movements were shown together without following a chronological order. Even the exhibition labels and catalogue captions omitted the artworks’ dates. Traditionally, the Americans promoted their art at the Venice Biennale within stylistic frameworks. The European public measured the importance and success of American artists by comparing their work to European art through the main criteria of stylistic influence and originality: the resulting judgment was, most of the time, tepid if not dismissive.34 Through the theme of the city, however, Kuh could present American art as the expression of a uniquely American urban landscape and social environment while still acknowledging the stylistic influence of the early twentieth-century European avant-gardes. Kuh, therefore, did not choose one of Lewis’s most recent canvases for the Biennale; she picked Cathedral 1950, which, in her view, incorporated some of the unique characteristics of the American city emphasised in her show.

Fig.4

Fernand Léger

The City 1919

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

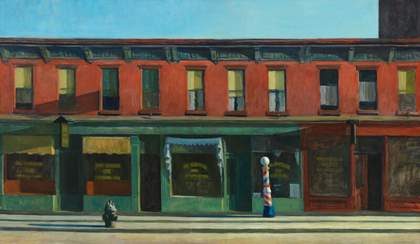

Fig.5

Edward Hopper

Early Sunday Morning 1930

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

© Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper

Kuh was not new to a thematic approach as a way to reach a public that was new, and in some cases even hostile, to the kind of art that she presented. In her pioneering work in museum education of the previous years at the Art Institute of Chicago, Kuh carefully avoided ‘the secret language of art specialists’ and always referred to real life and widely shared experiences.35 Through her work as an educator she came to realise that the general public did not have patience for ‘names, dates or “isms”’; on the contrary, thematic, non-chronological presentations gave her the freedom ‘to explore modern art in relation to contemporary life, using the familiar world around us as the point of departure’.36 In her books, shows and lectures conceived for the American public, she had already treated the city as a defining and easily relatable modern experience; and she presented it as a major source of inspiration for artists who, not differently from anyone else, reacted to the urban environment in a variety of ways. In Art Has Many Faces she contrasted, for instance, the reaction to the city displayed by Fernand Léger in The City 1919 with that of Edward Hopper in Early Sunday Morning 1930 (figs.4 and 5): ‘one man sees the city as an exciting stimulant, the other, more romantically, as a source of loneliness and isolation’.37

In the context of the Biennale, this theme took on a new didactic function, as a tool to explain the uniqueness of American art to a European audience. The American metropolis, and especially New York, was already part of the Europeans’ imagination and understanding of the United States, through countless books, magazines and films, and it was now reaching a peak of popularity with the mid-1950s wave of Americanism.38 As Kuh wrote in a press release, ‘The one contribution of America to world culture which is universally respected for both its visual and technical aspects is the architecture of our skyscrapers.’39 Kuh could, therefore, use a familiar and recognisable setting – the American metropolis – to contextualise art from a different continent, and especially abstract expressionism, in a way that was both accessible and appealing to the European public.

Lewis’s work suited Kuh’s goal to contextualise abstract expressionism through the theme of the American city both formally and conceptually. A non-representational painting, Cathedral evokes the cityscape of New York through its main formal qualities –grid composition, verticality and luminosity – without illustrating it. By comparing the American metropolis to a cathedral, the title linked the American cityscape to an architectural tradition that was familiar to the European public; but it also expanded the idea of ‘painting the city’, which was announced in the exhibition title, beyond the literal meaning of actually representing it. In the catalogue Kuh discussed Lewis together with Joseph Friebert and Mark Tobey as artists focused on luminosity and new perceptions of space that were distinctive in the American city: ‘American cities, in contrast to those of Europe, are visually more alive at night than during the day. The interplay of lights snapping on and off combines with streaming traffic to transform hitherto accepted dimensions. Positive becomes negative; perspectives flatten out and up.’40 This idea of a new spatial experience in the American city was instrumental to her explanation of abstract expressionism. Whereas art critics would commonly resort to the specialised vocabulary of formalism, phenomenology or existentialist philosophy to address abstract expressionism’s interest in scale and the body, Kuh explained, ‘Men like Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning in no sense paint city scenes but their work emerges from New York … One senses that these canvases are intended less to be looked at than entered into. They envelop one with the same insistence as the city itself.’41 Through New York and its current appeal among the Italian public, Kuh made the notion of space in abstract expressionist painting accessible, attractive and American. Lewis had an instrumental function in this process but was ultimately left out of Kuh’s main emphasis on Kline, Pollock and de Kooning.

The luminous colours of Cathedral helped Kuh introduce an important aspect of the experience of the American city to the European public. Lewis’s painting evoked simultaneously the stained-glass windows of a cathedral and the advertisements of Times Square. Still, his use of multiple layers of black paint and of bright colours deceived the eye, in Kuh’s interpretation, making it impossible for viewers to determine the exact painting process and to distinguish positive and negative, figure and ground. The resulting effect was one of pulsing lights and inverted perspectives described by Kuh as quintessential characteristics of the American city. All this, once more, served Kuh’s purpose to provide a context and an interpretive key for another artist that she promoted more strongly than Lewis: ‘This emphasis on the miracle of light’, she wrote, ‘has best been expressed by Mark Tobey who actually invented a new kind of painting called “white writing” which celebrates the iridescence of our cities’.42

Emphasising diversity

Fig.6

Jacob Lawrence

Chess on Broadway 1951

Private collection

© Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Art Resource, NY

Kuh focused on diversity as another key feature of the American metropolis. Within this framework she gave prominence to Lewis by naming him among only a few other artists in the press release for the show:

The earliest work is by John Marin, painted in 1910, of New York; the latest a still unfinished picture by Ivan Albright … The exhibition includes such unknown painters as Charles Oscar, George Mueller, and Fred Berman, as well as world-famous American artists like Mark Tobey, the late Lyonel Feininger, Willem De Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Edward Hopper, and two young, brilliant Negro artists, Jacob Lawrence and Norman Lewis.

Ignoring stylistic tendencies, here Kuh emphasised the diversity of age, degree of recognition and race in her show. The exhibition used the rhetoric of the American metropolis as a vibrant and multifaceted environment with multiple cultural roots, which resounded with European expectations and simultaneously resisted anti-American tropes: Kuh used the cliché of the American melting pot, which became popular in the 1950s, to counter European intellectuals’ frequent accusations of racism and segregation as ingrained in American society.43 Diversity showed in the iconography of the exhibition through some of its most often reproduced paintings: Bernard Perlin’s depiction of orthodox Jews (Orthodox Boys 1948, Tate N05956),44 Shahn’s representation of the San Gennaro procession in Little Italy,45 or Lawrence’s portrayal of black people and white people playing chess together (fig.6). The roster of invited artists emphasised diversity as well. The inclusion of two female artists (Hedda Sterne and Georgia O’Keeffe), although very small in number compared to the thirty-three men in the show, still exceeded previous post-war shows of American art at the Biennale, which had featured only men. More importantly, the prominence given to Sterne was exceptional: her painting New York 1955 (private collection) was one of only three colour illustrations in the entire catalogue and it appeared in the frontispiece. Artists with Italian origins were especially emphasised: Joseph Stella, Conrad Marca-Relli and Nicolas Carone (all Italianised as Giuseppe, Corrado and Nicola).46 In this scheme, Kuh identified Lewis as one of two African Americans – a statement repeated in a number of reviews.

Kuh, however, did not discuss Lewis’s experience of the city and the work inspired by it as conditioned by the fact that he was black and that he grew up and worked in Harlem. This was in part due to the artist’s own rejection of specifically African American subject matter and of social realism in his paintings. Although he never abandoned African American political activism, he divorced it from his work, stating: ‘I used to paint Negroes being dispossessed, discrimination, and slowly I became aware of the fact that this didn’t move anybody, didn’t make things better.’47 On the other hand, Kuh emphasised the centrality of African American subject matter in Jacob Lawrence’s work: ‘Lawrence frequently used his own people as subjects. With strident color and staccato shapes he extracts pathos, suffering and gaiety from life in Harlem and the South.’48 In Lewis’s case, she emphasised the ambiguity of his work: ‘Lewis tends toward a subtle technique where suggestion replaces representation. Melting and evasive forms are characteristic of both his drawings and paintings.’49

Recent scholarship has suggested that reflection on blackness has in fact never disappeared from Lewis’s work. Art historian Mia Bagneris has argued that even after his turn to all-over, abstract painting in the late 1940s, Lewis still referred to black culture in two main ways: in his iconography and titles, through direct references to black culture, especially night life in Harlem; and formally, by literally exploring black as a colour in his most well-known series, the Black Paintings (see, for example, America the Beautiful 1960, private collection).50 Art historian Andrianna Campbell has convincingly shown the interconnectedness between race and the nuclear theme in Lewis’s work, with its dualistic value of progress and destruction.51 Kuh, however, did not select one of Lewis’s many canvases dedicated to jazz music, for example; she chose a painting by Lewis with a clear visual reference to the theme of the American skyscraper as a new cathedral.

It could be argued that the show’s organising principle of diversity allowed Lewis’s work to be noticed by an already receptive audience. Yet that idea of diversity was precisely what made Lewis’s work remain noticed but not understood: partly because Lewis was not overtly taking on African American subject matter and partly because the implicit connections between his work and African American culture were hard to tease out. While ambiguity was, undeniably, Lewis’s deliberate choice, it was used instrumentally by Kuh for her own agenda: Lewis and his painting Cathedral helped her connect various parts of her narrative and especially the unique experience of the American metropolis (perceptions of space, luminosity and diversity) with American abstract expressionist painting.

The reception of Kuh’s show

Designed with the European audience in mind, American Artists Paint the City was extremely unpopular with American audiences. In Chicago, artists and critics disapproved of the prominence that Kuh gave to New York and the New York School. The New York Times criticised her decision to stage a large survey show as opposed to a more in-depth presentation of fewer artists, explaining that Kuh’s choice ‘practically precluded any chance of an artist being considered for a prize’.52 Milton Gendel, writing in Art News, disagreed with the selected theme (‘artists do not paint the city, they paint pictures’) and accused Kuh of flirting with Italian clichés about America: ‘they have given the local press an opportunity to air such venerable commonplaces as “melting pot” and “hectic rhythm of New World life”.’53 Even the notoriously taciturn Pollock spoke up in order to reject Kuh’s reading of his work as emerging from New York City: ‘What a ridiculous idea,’ he said, ‘expressing the city – never did in my life!’54 As for Lewis, he was not heavily involved in the organisation of the show as the loan of his work was done through his gallerist, Marian Willard, and his participation in the Biennale, despite being an important opportunity in his career, did not leave much trace in his archives.55

Yet Kuh’s intended audience – European critics from a wide variety of backgrounds – were very impressed with the show. At first glance, they appreciated its thematic clarity in an environment in which this was rarely on offer. With 34 countries and 663 works, the 1956 edition of the Venice Biennale was by far the largest and most diverse thus far. On top of that, visitors complained about the ‘sampling’ method used in most pavilions – Italy included – with which the organisers intended to illustrate the most important artists and movements of each national art scene, but which for most commentators felt chaotic and diffuse (the term ‘Babel’ was a recurring one). As such, many reviewers appreciated single-artist pavilions and, even more so, the American one, which presented the only group show in the entire Biennale with a cohesive theme.56 Most people admired the diversity of the US pavilion and frequently contrasted it with the Soviet Union’s display, which they criticised as monotonous – despite the inclusion of no fewer than 72 artists – for its homogeneity of style (socialist realism) and its celebratory tone. By contrast, the United States was widely praised as the best pavilion of the year for its combination of clarity and diversity.57

![Fig.7 Photograph illustrating Piero Girace’s review ‘Guardiamo nel Labirinto delle Città’, Il Popolo di Roma[?], 17 July 1956](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/fig.7_images_of_american_life_1956_crop.width-420.jpg)

Fig.7

Photograph illustrating Piero Girace’s review ‘Guardiamo nel Labirinto delle Città’, Il Popolo di Roma[?], 17 July 1956

Scrapbook, Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, IC/IP, I.A. 587

While stylistic variety had characterised previous American exhibitions at the Biennale, Kuh’s show was especially valued for its emphasis on cultural diversity. Particularly concerned with the apparently subordinate condition of the Italian American population in the United States, many Italian reviewers appreciated the inclusion of three artists with Italian origins. One critic praised it for the prominence given to women.58 A few writers were pleased with the presence of two black artists, as emphasised in the press release, while one reviewer celebrated the diversity that emerged from the show and compared the American city’s multi-centred vitality to a ‘giant beehive’. The same reviewer illustrated his text not with a work in the show but with a photograph of African Americans in an unspecified night club (fig.7), oddly captioned: ‘Images of American life: in every night club, people dance to rock and roll, a dance imported from Africa.’59

Vocal supporters of the exchange between European and American art, like the Italian Venturi, the French critic Michel Tapié and the British writer Herbert Read, eagerly celebrated the US pavilion as the best of the entire Biennale. But Kuh also won the most unlikely supporters. Francesco Arcangeli, who promoted Northern Italian Informale painters with a localist emphasis on the ‘naturalist’ tradition of Caravaggio (1571–1610) and Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1665–1747), appreciated Kuh’s thematic choice as a similar interpretive strategy: ‘it indicates real and poetic reactions of the American artist and man to the world where he lives’.60 Even Marxist critic Mario de Micheli, an advocate of socialist realism, praised Kuh’s show in his review for L’Unità, the official newspaper of Italy’s Communist Party. He predictably appreciated figurative artists within the exhibition, such as Hopper, Jack Levine, Shahn, Arthur Osver and Perlin. However, looking through Kuh’s thematic lens, he also liked the abstract artists: ‘they have a more authentic tone, I would say, more adherent to a real situation, less gratuitous than, for example, those in the Italian pavilion’.61 Kuh’s interpretation helped Italian critics see American abstract expressionism as ‘real’ – or at least more real than types of Italian abstraction, which they regarded as inauthentic or rarified.

Kuh’s show succeeded where previous shows had failed in that it provided the Italians with a context and a viable interpretive key for American art in general, and for abstract expressionism in particular. Arcangeli contrasted the disorienting effect of an earlier encounter he had had with Pollock’s work with his experience of the current show: ‘Biennale after Biennale, the situation of American art became more clear.’ He described his confusion when he first encountered Pollock’s painting in 1950 (a ‘vertigo’), then Hopper in 1952, and Shahn and de Kooning in 1954. ‘But it was only with this Biennale’, he concluded, ‘that the presence of thirty-five painters gives, although imperfectly, a lively and fervid picture of the multifaceted panorama of artistic energies active today in America.’62 In Arcangeli’s account, a lack of context, both cultural and artistic, made the earlier displays of American art feel disorienting. Kuh’s show provided Italian critics with a varied yet cohesive survey of American art.

Provided with this context, Arcangeli could call Pollock and de Kooning the most interesting artists of the entire Biennale.63 In his review for the popular magazine L’Espresso, Venturi stated further that: ‘the United States sent a show including interpretations of the city made by their artists – almost all of them abstract – of which Pollock and Tobey are the most important.’64 As we have seen, many praised Lewis and some of the most authoritative critics reproduced Cathedral, but they failed to discuss his work directly.65 In retrospect, Lewis’s historical role, like that of Kuh’s show, was to facilitate the success of other abstract expressionist shows held in the following years.66

In the next two years, a series of exhibitions helped to establish a canon of American abstract expressionism.67 The most influential shows in Italy were the retrospective of Pollock’s work at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome and the large survey The New American Painting at the Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna in Milan, both of which opened in 1958. That same year the Venice Biennale’s Grand International Prize went to Tobey, who was the first American to win the award since James Abbott McNeill Whistler in 1895. The success of these events among artists and critics was accompanied by a new interest among Italian collectors.68 None of these institutions and private collectors, however, exhibited or collected Norman Lewis. Yet while his work and the exhibition American Artists Paint the City were soon largely forgotten, they had made a strong contribution to the international acceptance and success of abstract expressionism in 1956.69