Discussing the design of the F-117 stealth bomber at the time of the Gulf War (1990–1), French cultural theorist Paul Virilio made the point that the shape of the plane was dictated by the way it resisted representation: the plane was intended to be undetectable by radar and so the absence of a mark representing the plane on the radar screen was the anticipated outcome of its design.1 The peculiar, angular shape of the F-117 is engineered to deflect radar waves, every access panel irregularly saw-toothed and the skin of the aircraft made up of small, flat surfaces that act like mirrors to scatter incoming radar signals. Engines and weapons are positioned inside the fuselage, and the plane’s external surface is coated with radar absorbent materials. So aerodynamically ungainly that it was nicknamed the ‘Wobblin’ Goblin’, the F-117 must be flown using a so-called ‘fly-by-wire’ electronic flight control system. The form of representation, then, determines the form of the object, reversing the conventional expectation that representation re-presents a preceding object. This is more than camouflage, where the pre-existing form of the object is preserved through a concealing disruption of surface; rather, the form of the stealth bomber is determined by its intended unrepresentability. The mode of representation and its limits are the primary factors in deciding the shape the object is given.

How plausible might it be to extend this logic to entire landscapes? Is it conceivable that representations might govern topography? If radar determines the form of the bomber, do photographs produce the material spaces that they also reproduce? This article considers how the history of landscape photography, and Western US landscape photography in particular, contributed to the large-scale restructuring of terrain by military-industrial interests after the Second World War. The appropriation of millions of acres of Western land for military purposes after the attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941 (under the principle of eminent domain, whereby the federal or state government is able to claim private land for its own use), removed huge areas of one of the most photographed landscapes in the world from public scrutiny. Landscape photography of the American West has historically been about showing what is there (natural resources, available land, sublime geomorphology) and what is not there (no cities, no people, sublime vacancy). The installation of bombing ranges, experimental research facilities, test sites, waste dumps, and all the paraphernalia of advanced military-industrial power in the West makes use not only of abundant, under-populated space but also of the notion of ‘emptiness’ itself, which is mobilised as a resource in the concealment of military activity. The archive of representations that encodes the Western landscape as empty in this way makes a vital contribution to national security.

It is precisely because it has been, and continues to be, endlessly photographed that this militarised landscape has remained hidden, not just because photographs of ‘wilderness’ act as a camouflaging screen behind which military activity can take place or because the landscape functions as a screen upon which romantic projections of openness can be thrown, but because the military has shaped its presence according to what it will look like as a photograph. In other words, the form of militarised space has been determined by what the mode of representation will and will not show. Although this strategy of open concealment is not confined to the American West and is arguably typical of military and industrial enterprise where the un- or de-populated spaces favoured by landscape photographers are also the most available (because they are unwanted, cheap and remote) for exploitation, the particular convergence of photographic and military-industrial histories in the West makes it especially pertinent as the site upon which issues of visibility and hiddenness have been played out in recent decades. If landscape photography since the Second World War has sought to address, with varying degrees of criticality, the force exerted by romantic and modernist sensibilities on the representation of Western space, it has also had to contend with the fact of military occupation as a present absence. Where the explicit purpose of Western photography has been to show what is hidden there, as it is in the work of Peter Goin, Richard Misrach, Trevor Paglen and others, the question of what exactly there is to see in an ‘empty’ landscape is complicated by the fact that landscape photography as a mode of representation is to a large extent an enabling function of concealment. Landscape photographs of military and militarised places must somehow engage in showing what cannot be seen – in showing hiddenness itself.

Excessively obvious

The title of this article borrows from the famous detective story by Edgar Allan Poe, ‘The Purloined Letter’ (1844), where a stolen letter is concealed by being placed in plain sight. Poe’s tale is about questions of seeing and reading, about spatial apprehension and models of analysis. The American West can be described as a purloined landscape because much of it has been withdrawn from public access (some might even say stolen), but it has also been left open, apparently untouched and as nature intended. The truth about what goes on in this landscape, like the letter, remains hidden because it is right there, rendered invisible by being thoroughly exposed to the field of vision. Poe’s tale provides a rich and complex interrogation of duplicity and power, crime and detection, and the doublings, repetitions, and degrees of blindness and insight addressed in the story speak directly to contemporary issues of state secrecy and the possibility of resistance and accountability. Most troubling, perhaps, among Poe’s insights in this and his other foundational detective tales – ‘The Purloined Letter’ is the last of Poe’s celebrated trilogy of ratiocinative detective stories, after ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ (1841) and ‘The Mystery of Marie Rogêt’ (1842) – is the proposition that the most effective work of detection demands a mind and sensibility indistinguishable from those of a criminal. Only from the inside of monstrous ingenuity, according to Poe, can the motivations and manoeuvres of such an intelligence be properly grasped. What this means in the context of military-industrial power and landscape photography is that the line between concealment and exposure, hiding and seeing, is not a line at all; rather, site and representation are each concealing and exposing at once.

In the 1970s Poe’s ‘The Purloined Letter’ became a central text in post-structuralism – the theoretical approach which had first emerged in France in the 1960s – because of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s famous seminar on the story (1957/1972), followed by the philosopher Jacques Derrida’s response to Lacan (1975), the literary critic Barbara Johnson’s assessment of the Poe/Lacan/Derrida triptych, and the subsequent flurry of articles generated by this heavyweight interrogation.2 These readings approached Poe’s tale as a parable of the act of analysis, and while it is not the intention of this article to rehearse those complex and labyrinthine discussions, it is worth noting that the splitting and doubling, the reversals and absences that drive ‘The Purloined Letter’ and the critical commentary produced on it, are as much about deferring resolution as they are about solving puzzles. Although the riddle of how the hidden letter is found is revealed to the reader, the content of the letter itself is never disclosed. This absence at the heart of the story – the content that is the essential motivation for concealment and theft, and yet utterly disregarded and unimportant for the telling of the tale – is what generates the proliferating interpretations that are themselves circling an unknowable cause. In a similar fashion, photographs of militarised landscapes that ostensibly confront the fact of secrecy are more often than not images of absent content, in the sense that what they show is military power’s hiddenness rather than the content of what is hidden. Like the undisclosed content of Poe’s letter, the invisible sites of military power can only be detected through their effects.

As Dennis Porter (a specialist on French critical theory who translated Lacan’s writings) has acknowledged, ‘The Purloined Letter’ is a parable of analysis as power, and the struggle for the letter is played out between different modalities of power/knowledge. These are embodied in the story by the politician (the Minister D–, whose ‘lynx eye’ spots the Queen’s private correspondence and steals it), the police (the Prefect charged with finding the stolen letter), and the poet/detective (Dupin, the one who ultimately locates the letter turned inside out in a letter rack).3 Power here does not reside in an object (the letter) but circulates through the network of functionaries and institutions as they manoeuvre for position. ‘The Purloined Letter’ is about different readings of space, different modes of reading and seeing, and the struggle between these modes for insight into the motives and strategies of others. In the end, the Euclidean model of analysis represented by the Prefect’s gridding and dividing of space, despite being the officially sanctioned investigative method, fails to grasp what the admixture of mathematics, poetry and politics characteristic of D–’s and Dupin’s approach is able to achieve: the successful theft of the letter and its subsequent discovery. Outstripping the normative power of understanding as represented by the police, the real power play takes place between the politician and the detective, the monstra horrenda or ‘unprincipled [men] of genius’ who work in the warped spaces inside and beyond the law.4 What ‘The Purloined Letter’ offers is an allegory of how secrecy relies upon the notion of transparency as a virtue, how transparency is shaped by the demands of secrecy, and how, ultimately, any apprehension of the secreted must involve a move beyond normative assumptions of the self-evident.

In order to explain how he came to spot the letter, Dupin uses the analogy of a ‘game of puzzles’ played on a map. One player, he says, invites another to find a word, ‘the name of town, river, state or empire’, for example, ‘upon the motley and perplexed surface of the chart.’ While a ‘novice in the game’ thinks that the biggest challenge is to ask an opponent to find the ‘the most minutely lettered names’, the skilled player selects those words that ‘stretch, in large characters, from one end of the chart to the other.’ Words denoting vast areas ‘escape observation by dint of being excessively obvious; and here the physical oversight is precisely analogous with the moral inapprehension by which the intellect suffers to pass unnoticed those considerations which are obtrusively and too palpably self-evident.’ Thus, the best way to conceal the letter is by ‘not attempting to conceal it at all’ because its ‘hyperobtrusive situation’ is part of a ‘design to delude the beholder into an idea of [its] worthlessness’.5 Scale, here, works as concealment not by hiding away that which is intended to be missed, but through a degree of amplification that makes the information occupy the entire field. Openness is a function of hiddenness and Dupin’s explanation is caustic in its assessment of the failure of the player who cannot see the big picture: ‘physical oversight’ (simply not seeing) is also ‘moral inapprehension’ because the intellect allows the too-obvious to pass unnoticed. Successful concealment, then, is less about finding properly secret places, since the fine-grained investigation of space, as the Prefect’s searches demonstrate, will show everything but reveal nothing, and is all about delusion. It is by ‘delud[ing] the beholder’ that D– is able to keep the letter out of the Prefect’s grasp while at the same time keeping him busy pursuing the logic of his own expectations.

The large words on the map, of course, recall the acquisition of territory through naming and mapping, the conversion of space to text and the power of possession contained within that textualising act. For many years the territories that would become the Western United States were designated on maps of the region as the Great American Desert, the word ‘desert’ here signifying semi-arid terrain and also emptiness and worthlessness. Through the course of the nineteenth century, the West was explored, mapped and documented in order to provide information for industry, commerce, scientific and military interests, and, increasingly with the expansion of the railroad, for tourism – driven in no small part by the circulation of photographic images of the Western landscape.

The mountains, rivers, forests and deserts of the Western United States have been subject to the photographer’s relentless attention since the invention of the camera, and Western landscapes have become global iconic signifiers of American space and American values. Indeed, the Western landscape is bound up with the rise of photography as a scientific and military technology, through the work made by, among others, Timothy O’Sullivan, Carleton Watkins and Alexander Gardner during the government surveys conducted after the American Civil War, and with the rise of photography as an art form through the influence of, to name only the most prominent practitioners, Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. The survey photographers were retrospectively incorporated into the canon of American landscape photography as precursors of the so-called ‘straight’ aesthetic of crystalline, thickly detailed, deep focus prints typical of the Adams-Weston school during the 1920s and 1930s, at the point when photographs were being collected and exhibited in museums and galleries as artworks.6 Serving to articulate, during the years of American economic and military ascendancy following the Second World War, a set of national virtues presented as incarnated in the land itself, the work of Adams, Weston and others became the default mode of US grandeur, as seen for example in Ansel Adams’s Half Dome from Glacier Point in Winter c.1940 (fig.1). While the growth of military-industrial power in the post-war West drove a radical reconstruction of social life through the expansion of cities and suburbs, massive population growth, demographic mobility, and the explosion of commodity consumption, the pristine abstractions of Adams’s and Weston’s monochrome Western sublime stood as advertisements for an authenticity sharpened (rather than contaminated) by representation, as if the image did not distance but instead brought closer the real power of places as natural fact. Shorn of any contextualising information, foregrounding the triumph of technique and the language of abstract natural form, the ‘straight’ Western photograph simultaneously delivered artistic ‘vision’ and documentary information in a form that was at once plain-spoken and open to any number of symbolist-inspired extrapolations. Packed full of empirical visual data but formally available to subjective interpretation, the Western landscape photograph managed to combine the inventorial drive of the technocrat with the libertarian impulse of the expressive subject. In this way, the Adams or Weston print manages to hold together in sleek propinquity the agonistics of an emerging US Cold War identity: total administrative command of the object world coupled with a notionally limitless freedom for individual self-realisation.

Fig.1

Ansel Adams

Half Dome from Glacier Point in Winter c.1940

© Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust/CORBIS

The Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank, traveling across the United States in 1955 on a Guggenheim fellowship, delivered a deliberately awkward riposte to the Western sublime with The Americans (1959), an 83-image distillation of over 28,000 photographs made during his road trips. The US response to The Americans was initially underwhelming. Frank’s indifference to the aesthetics of the fine print and the rules of proper composition drew negative reviews, which were critical of his grain and blur, the general clutter of the framing and the collection’s apparently nihilistic approach to blank American spaces and their bored, stupid or existentially lost inhabitants. Yet even Frank’s assault on Eisenhower-era ennui could be recuperated in a relatively straightforward fashion, with Jack Kerouac’s introductory essay giving The Americans Beat Generation kudos, and the images positioned more accommodatingly as personal expression rather than radical critique. Indeed, Frank’s work, read as subjective documentary, became a model for an emerging generation of auteur photographers whose ascendancy was marked in 1967 with the ‘New Documents’ exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, curated by John Szarkowski, which showcased the work of future stars such as Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and Gary Winogrand.

The real challenge to the Adams-Weston nexus came not from Frank and his descendants, whose idiosyncratic portraits and street scenes have more in common with high-end reportage than the protracted stillness of the landscape view, but from an ostensibly more formally conservative quarter. The ten photographers gathered in the ‘New Topographics’ exhibition – curated in 1975 by William Jenkins at George Eastman House in Rochester, New York – shared with Adams and Weston a commitment to the ‘straight’ photograph, but the outcome was strikingly different. Like the modernist landscape photographers, the New Topographics photographers favour the unmanipulated print, long depth of field, thick detail, classical composition, pristine reproduction and largely depopulated vistas. In works by Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke and others, the same Western landscapes made iconic by Ansel Adams and Weston are revisited but this time the vernacular architecture of urban sprawl and commercial exploitation fills the frame. This is ‘straight’ photography put through the wringer of historical self-reflexivity, whereby technical excellence is deployed to craft hard images of engineered entropy and where the abstracting tendency of deep focus reproduces the serial forms of manufactured homogeneity.7 The ‘New Topographics’ exhibition offered a model of landscape photography released from the expressivist tendency the ‘New Documents’ group had inherited from the masters of modernism. Instead, the New Topographics delivered a blank style, however crafted, that echoed the indifferent gaze of the camera-as-recording-device utilised by surveyors, geographers and other non-artistic agencies.

While the New Topographics photographers focus largely on the domestic transformations of Western space that were a consequence of post-war militarisation, the 1980s saw the emergence of a group of photographers who more directly addressed the military-industrial landscapes adjacent to New Topographic suburbia. Robert Del Tredici, Carole Gallagher and other members of the Atomic Photographers Guild (an international grouping established in 1987) shared, as Del Tredici explained, ‘a documentary bent and a hunger for unseen evidence … an eye for innuendo, a taste for paradox and the ability to walk among conspiracies and phantoms’.8 Alongside the more traditional documentary concerns of Del Tredici and Gallagher, the rise of colour photography during the 1970s, pushed by Szarkowski at MoMA and already evident in Stephen Shore’s contribution to the New Topographics exhibition, marked, in the work of Peter Goin, Richard Misrach, John Pfahl and Terry Evans, among others, a distinctive shift away from the fine monochrome prints of the modernist tradition while amplifying the connection to the nineteenth-century Western sublime characterised by painters like Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church. Pfahl’s work on power plants, missile sites and other so-called ‘altered landscapes’, Goin’s images of nuclear test sites and engineering projects, Misrach’s layered interrogation of desert land use, and Evans’s Midwestern military-industrial pastoral all combine the chromatic range of Western US landscape painting with the blank gaze of the New Topographics.9 Through the reactivated Cold War years of the Reagan presidency (1981–9) and into the 1990s, as relaxing security restrictions began to allow access to more sites, American photographers produced a body of images that comprise an archive of secrecy, dissimulation and ‘peacetime’ devastation on an unprecedented scale.

There was a brief moment when the photographic record of secret military places looked like the backwash of history, but since 9/11 the work of Goin, Misrach and others from the 1980s and 1990s has come to appear more like a prelude to the deeper and more extensively securitised landscapes of the present. Alongside the lockdown of twenty-first century US militarised space, the inaccessible war zones of Iraq and Afghanistan (visually managed through the exclusion of all but ‘embedded’ photographers) and the swathes of hidden territory that service globalised trade have become the focus of landscape photographers determined to address the limits of visible power. The interrogation of military and/or industrial secrecy is a dominant concern for photographers like Michael Light and David Maisel, who deploy aerial views to explore large-scale environmental exploitation; in Trevor Paglen’s pursuit of ‘black sites’, rendition flights, military satellites and drones; and in the work of the Canadian Edward Burtynsky (see, for example, Oil Spill #2, Discoverer Enterprise, Gulf of Mexico, May 11, 2010 2010, Tate L02996) and German photographers like Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth, who focus on the catastrophic proportions of globalised industry. The development of digital photography has enabled the production of huge, overwhelmingly detailed prints, and part of the power of Burtynsky’s, Gursky’s and Struth’s images lies in their use of scale to saturate the visual field with mountains of waste, endless production lines, monstrous machines or oceans of shipping containers.

Among conspiracies and phantoms

The ‘hunger for unseen evidence’ in much landscape photography since the New Topographics coincides with the collapse of the post-war consensus in the United States and Europe (the New Topographics exhibition opened in January 1975, between the resignation of Richard Nixon and the fall of Saigon, marking the end of the Vietnam War) and the rise of neoliberalism. If the Cold War established a global field where everyone everywhere is already a target and also potentially a double agent, neoconservative eschatology has served to ramp up periodically the paranoia through the manufacture of nebulous, almost metaphysical enemies, from Ronald Reagan’s ‘evil empire’ to George W. Bush’s global war on ‘terror’. The thick scrim of screens and filters through which security is notionally maintained has produced a sensibility sceptical of appearances and permanently aware of secrecy as the medium through which daily life is experienced. Indeed, once secrecy becomes the default mode of security, openness is no longer a sign of liberty but either a suspicious bluff misdirecting attention from a greater secret or evidence of dangerous exposure to threat. Rather than celebrating openness as proof of transparency, then, the most effective demonstration of legitimating power is to display secrecy openly. This is what the political scientist Michael Rogin called, with reference to Reagan’s Central American counterinsurgency actions during the 1980s, a strategy of ‘covert spectacle’ – whereby secret military operations are played back domestically as a confirmation of hegemony – and what the cultural theorist Jack Bratich has more recently termed ‘spectacular secrecy’.10

For Bratich, ‘[s]ecrecy has become integrated into (no longer expelled from) the spectacle … This spectacular form generalizes secrecy into public and private domains, making revelation no longer the end to secrecy, but its new catalyst’.11 In terms of a photography hunting ‘invisible evidence’, what this means is that the resulting images no longer locate evidence by making visible what was concealed but are instead more ambivalently evidence of invisibility. While Del Tredici’s and Gallagher’s documentary projects sought to bring to light the hidden apparatus of a dispersed nuclear arms industry (Del Tredici) and populations exposed to radioactive fallout (Gallagher), in the end their work relies upon a commitment to an optics of exposure that does not entirely address the collapse of secrecy into openness that the purloined landscape has achieved.12 Weapons factories and communities blighted by contamination may not have been as visible before these projects but they were known to have existed; they were not exactly secret but were underexposed. What is different about Goin’s and Misrach’s nuclear landscapes and Paglen’s black sites is that the images are less concerned with exposing what is concealed and more invested in interrogating the limits of what the photograph can deliver in terms of evidence. This reflexivity is an attempt to move beyond what Dupin (to return to Poe’s story) calls the ‘moral inapprehension’ of mistaking openness for transparency in order to operate in full awareness of power’s duplicity. To make this move, however, as Poe demonstrates, requires the detective to think like the criminal; only through reproducing the methods of the deceiver can the nature of deception be properly apprehended.

The massive increase in military spending during the 1980s was accompanied by heightened secrecy concerning what the money was being spent on, even as the federal government belatedly accepted responsibility for earlier policies of open secrecy, such as the internment of Japanese-Americans during the Second World War and radiation exposure during uranium mining and overground atomic testing.13 The fact that photographers like Goin and Misrach were able to access high security US military sites during the 1980s might suggest a slackening of Cold War security restrictions, although any concession to transparency must be understood as part of a broader strategy of concealment which continues the delusion of openness by showing in order to hide. What this doubleness means is that, like Dupin, the photographer has to work according to the logic of the deceiver if the nature of concealment is to be addressed. As Paglen writes, discussing the observer effect: ‘To observe something is to become a part of the thing one is observing.’ In the case of the secret world, ‘the more you look at it, the more you learn to see. At some point you see it all around you and realize that you’ve somehow become a part of it’.14 The dilemma for Dupin, and for the photographer of military secrecy, is how to become part of the duplicitous world without merely reproducing the monstrous ingenuity of the adversary. As far as Dupin is concerned, it is hard to say whether he succeeds in distancing himself from the Minister D– as much as he might wish. After all, it is not enough for Dupin to find the letter; he is compelled to write a cryptic response for D– as revenge for ‘an evil turn’ the Minister had once committed upon the detective, suggesting that his own motives are not untarnished by arch and selfish impulses.

In a similar fashion, one of the dangers of a photography that would address the politics of landscape representation and the concealment of power is that it ends up serving the covert spectacle it appears to challenge. Not only does the work of Goin, Misrach and Paglen seem to provide evidence that it is possible to see, however obliquely, something of the secret state, but also the means they deploy – the ‘straight’ aesthetic of the landscape tradition with its reliance upon classical composition and the history of the retinal sublime – is never far away from complicity with the diversionary tactics of military-industrial self-erasure. There is, though, as Poe’s story makes clear, no ‘outside’ from which to objectively engage with the perpetrator of crimes; indeed, the belief in a myth of an ‘outside’ is already a failure to engage. The Prefect has much work to do, but it is all worthless since his methods are merely bureaucratic. Only from the inside of deception can D–’s power be encountered at all.

‘It’s easy to imagine’, writes Paglen, ‘that the antidote to state secrecy is more openness, more transparency in state affairs. That is, no doubt, a crucial part of a democratic project. But transparency, it seems to me, is a democratic society’s precondition; transparency alone is insufficient to guarantee democracy’.15 ‘Straight’ photography cannot deliver the kind of disclosure that transparency appears to offer, but it can put transparency to work. The kind of ‘straight’ photography produced out of, and about, secret places has to bend back on itself, like the letter folded inside out, in order to reveal the ways in which transparency is part of the lexicon of concealment.

Dominion every where

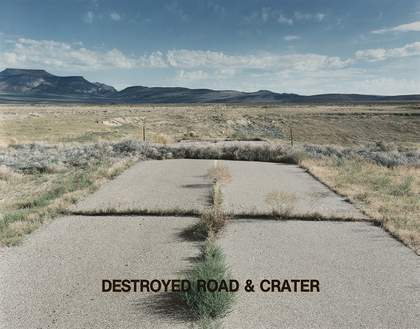

Goin’s Nuclear Landscapes series from the 1980s shares with British political photography of the same period, by artists like Willie Doherty and John Kippin, the strategy of placing brief statements across the image in order to disrupt the illusion of transparency and to insist upon the constructedness of the photograph as text. Doherty’s monochrome image/text pieces depicting the militarised landscapes of Northern Ireland use pointedly provocative language, such as ‘Remote Control’, ‘God Has Not Failed Us’ and ‘Last Bastion’. Kippin similarly signposts broader critical contexts in his photographs of British military and heritage sites, where statements like ‘Hidden’, ‘Nostalgia for the Future’ and ‘Shakespeare Country’ ironically jar with the content of the image. In Goin’s colour work, flat descriptive titles name the objects and spaces depicted in a kind of charred umber across the bleached desert surface: ‘Collapsed Hangar’, ‘Destroyed Road and Crater’, ‘Site of Above-Ground Tests Yucca Lake’ (fig.2). These are less committed to narrative and irony than Doherty and Kippin, and instead of opening up the photograph to interpretive contexts beyond the image, they tend rather to stunt allegorical or rhetorical unpacking. More than captions, these statements directly aggravate the blankness of the images, sometimes providing specific information about location and history, but more often than not merely repeating what the visual information already provides. Although the written text is a reminder that photographs are always coded, always read, the words are a form of excessive information, doubling the codes in semiotic overkill.

Fig.2

Peter Goin

Destroyed Road & Crater from Nuclear Landscapes 1987

© Peter Goin

Nuclear Landscapes shares with much American art of the 1980s a fascination with the banality of the strapline and the poetics of redundancy. The dumb reflexivity of the so-called ‘Pictures Generation’ (a title used to describe artists in the 1970s and 1980s who appropriated consumer slogans and mass media images), from John Baldessari’s West Coast pop-conceptual irony to Jenny Holzer’s LED truisms and Barbara Kruger’s masscult platitudes, is here put to work in flattening the spaces of the nuclear sublime and the visual rhetoric of Western landscape photography into a blunt what-you-see-is-what-you-get self-evidence. But this is the empty promise of openness that enables the maintenance of the open secret, since affectless denotation shows in order to hide, like Poe’s letter perched above the mantelpiece. What is missing from Goin’s photographs is the content of the letter, the power that is sustained by not being used. The text upon the surface of the photograph repeats in written form what is in the picture, but the circuit is closed since the written message does not reach beyond what is already there. The absent weapons, the departed personnel, the invisible fallout, the technological and administrative infrastructure, the government agencies, the arms race and the Cold War are unseen, but nevertheless remain the atmospheric conditions of possibility for the photograph and what it can show.

Richard Misrach’s photographs of the Bravo 20 bombing range in Nevada feature similar scenes of abandonment, the terrain hammered with craters and littered with rusted shell casings that look like beached sealife, actual dead fish strewn mysteriously across the desert flats, burnt-out school buses, and lurid ponds of unidentified effluent (fig.3). ‘The landscape’, writes Misrach, ‘boasted the classic beauty characteristic of the desert’, but it is also ‘the most graphically ravaged environment I had ever seen’.16 The Bravo 20 photographs were made during the late 1980s and their exhibition coincided with the US prosecution of the Gulf War, the work being shown in Las Vegas (November–December 1990), Reno (January–February 1991) and in San Francisco (September–December 1991). Misrach’s show was America’s homeland Desert Storm, the photographs offering on-the-ground evidence of US firepower that was largely unavailable from sources in Kuwait and Iraq. The long catalogue essay accompanying the photographs by the writer Myriam Weisang Misrach (Richard Misrach’s wife) reinforced the sense that the devastation in Nevada is by no means a 1950s Cold War remnant, by providing an account not only of the history of the bombing range, but also of the ongoing struggle between residents and the military over land use and compensation. If the Pentagon preferred to circulate live images made by cameras attached to Scud and Patriot missiles in the Gulf as evidence of US military vanguardism, Misrach deployed the conventions of American landscape photography to depict a perpetual war on the home front bereft of the sublime techno-futurism that was being offered to the global media as a triumphant post-Cold War ‘Revolution in Military Affairs’, to use a label which became especially prevalent after the Gulf War.

Fig.3

Richard Misrach

Personnel Carrier Painted to Simulate School Bus 1986

© Richard Misrach, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York and Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Los Angeles

On 26 February 1991, the day after Misrach’s Bravo 20 exhibition closed in Reno, Paul Virilio wrote that electronic battle and live coverage by the media ‘is nothing other than the strategic organization of a gigantic making-over of facts: that is, of a menacing blinding, a blinding of which everyone, civilian or military, is the potential victim’.17 In the face of the spectacular real-time secrecy of the Gulf War, Misrach delivers the open secret of the West as domestic battlefront, the power of the images residing less in what is revealed of military testing and more in the network of associations they generate. Misrach’s West recalls not only the tradition of Ansel Adams and the redemptive sublime of the Western landscape, now supercharged in post-apocalyptic polychrome, but also the invisible distant deserts of Kuwait. Bravo 20 collapses time and space, and speaks to the ‘menacing blindness’ that is achieved by the open secret; the bombing range signifies a domestic space screened off by Adams’s sublime and an overseas space screened off by Pentagon spectacle. The Nevada site is simultaneously close at hand and distant, identifying military violence at home and abroad that in each case has been withheld from view.

Goin’s and Misrach’s work, begun during the Reagan years, entered the public domain at the threshold of a new era for the US military, the moment when the heavy lifting of Cold War deterrence gave way to increasingly dematerialised, digitally mediated conflict. As Virilio noted at the time, the Gulf War revealed a new order of warfare that would produce new security challenges and new modes of deception. Nevertheless, what the recent work of photographers like Paglen demonstrates is the powerful continuities between Cold War secrecy and its contemporary iterations.

In Blank Spots on the Map (2009), Paglen’s account of his research into so-called US ‘black sites’ – locations where highly classified military activities take place – which took him from Nevada and Washington DC to Honduras and Afghanistan, the operating assumption is, like Dupin’s, that the hidden has to be somewhere. In other words, however secret, the laws of geography and physics must still obtain; through a process of elimination the spaces of the hidden can be located, if only in outline. When, for example, Paglen explains, ‘the government takes satellite photos out of public archives, it practically broadcasts the locations of classified facilities. Blank spots on maps outline the things they seek to conceal’.18 If the twists of Poe’s tale are wearisome, it is because maintaining and detecting secrecy is a game of proliferating complexity. ‘To truly keep something secret,’ Paglen continues, the outlines on the map ‘also have to made secret. And then those outlines, and so on. In this way, secrecy’s geographic contradictions (the fact that you can’t make something disappear completely) quickly give rise to political contradictions between the secret state and the “normal” state’.19 New modes of secrecy have to keep being invented in order to ‘contain those political contradictions’, and this is why secrecy ‘tends to sculpt the world around its own image’.20 Like the American poet Wallace Stevens’s famous jar in Tennessee, secrecy makes ‘the slovenly wilderness’ rise up around itself, ‘no longer wild’. And like the ‘gray and bare’ jar which, by being placed, alters all around it, secrecy takes ‘dominion every where’, sculpting, as Paglen writes, the world around its own blankness.21

Paglen has collected the code names and uniform patches of secret projects, gathered the signatures of fictitious identities used by operatives involved in rendition flights, pointed astronomical cameras at remote military installations and ‘black’ prisons, and photographed the trails of military satellites with the help of amateur sky-watchers. Among the images from this last project, called ‘The Other Night Sky’ and begun in 2007, are a number of photographs taken at iconic Western US sites, including the Tufa rocks at Pyramid Lake, Nevada, Half Dome in Yosemite National Park, California, and Monument Valley, Utah. Places like these are the staples of Western landscape photography and bound up with the iconography of the West from O’Sullivan’s and Watkins’s nineteenth-century survey photographs through Ansel Adams to the New Topographics, Goin and Misrach. Taken at night, the long exposure time necessary for Paglen’s images has streaked the stars into a series of short arcs all following the geometrical logic of the earth’s movement – except one, which cuts the other way. This is the satellite following its own trajectory, the countervailing scratch confirming Paglen’s point that the laws of physics can be made to yield secret intelligence (fig.4).

Fig.4

Trevor Paglen

KEYHOLE IMPROVED CRYSTAL from Glacier Point (Optical Reconnaissance Satellite: USA 186) 2008

SFMOMA

© Trevor Paglen

Like Goin’s text that is also part of the image it describes, Paglen’s satellite photographs taken from iconic vantage points are versions of the message in Poe’s story that Dupin archly pens on the discovered letter – a letter, once found, that he leaves in place for D–. The message Dupin sends is that he is D–’s double and knows what D– knows; as such, he returns the letter inside out and encoded with the sign of a code already cracked. What Paglen’s Western landscapes do is what so much of the work since the New Topographics has done, which is repeat the conventions of landscape photography, inserting themselves into that tradition and in the process altering the coordinates of that tradition. In the case of the military landscapes shot by Goin, Misrach and Paglen, one of the consequences of this retroactive intervention is to pull into the foreground the always already militarised condition of Western landscape photography, and the ways in which the manufactured national sublime has, from the start, been underwritten by space sculpting military-industrial interests. The landscape has been shaped according to the needs of the mode of representation, and the value of landscape photographs – a value transposed onto the terrain itself from its composition as images – so often lies in what they leave out: indigenous inhabitants, industrial devastation, military installations, prisons, toxic contamination, and the rest. Power resides in the circulation of images of sublime wilderness evacuated of content and that power is derived from an original act of theft.

But this still begs a question: ‘For a purloined letter to exist, we may ask, to whom does a letter belong?’22 Theft presupposes ownership, yet as Lacan wonders, ‘[m]ight a letter on which the sender retains certain rights then not quite belong to the person to whom it is addressed? Or might it be that the latter was never the real receiver?’23 In the case of the Western landscape as a set of images codified as a set of values (openness, liberty, democracy), the question of ownership must also pertain. Who owns those images – not to mention the places that the images depict – and those values that they might be purloined? And if secrecy sculpts the world around its own image, as Paglen argues, there is no destination for the letter that is not already the location of the addressee, no outside the condition of being purloined from which to read its full extent.

Lacan’s etymological investigation of the word ‘purloin’ yields a combination of the prefix pur- related to the Latin pro- (‘in so far as it presupposes a rear in front of which it is borne, possibly as its warrant, indeed even as its pledge’); and the old French word loigner: ‘a verb attributing place au loing (or, still in use, longe), it does not mean au loin (far off), but au long de (alongside)’.24 From this, Lacan understands ‘purloin’ to mean ‘putting aside’, and concludes that ‘we are quite simply dealing with a letter which has been diverted from its path; one whose course has been prolonged (etymologically, the word of the title), or, to revert to the language of the post office, a letter in sufferance [i.e. held up in delivery]’.25 So, a letter that is not quite the property of the sender nor of the receiver is held up, delayed, its final destination unreached. Thought of this way, the purloined landscape of the American West is a set of values put aside, held up in delivery. The values conventionally attributed to images of the Western landscape are suspended in the images but not received.

In learning how to track secret satellites from hobbyist Ted Molczan, Paglen is struck by Molczan’s explanation for his commitment to the project, which he describes as being ‘about democracy’:

There are elements out there who want to keep everything secret. I try to put pressure in the other direction. I try to put checks on that power. When people ask me about what gives me the right to make these decisions, I say, ‘Citizenship in a democracy gives me the right to make these decisions.’ I don’t break in, I don’t steal stuff. I assert my right to study the things that are in orbit around the earth and study them with the belief that space belongs to all of us. I exercise my right to know what’s there.26

Molczan is here claiming his right to read the letter by intercepting it from its suspended condition, hidden in plain sight. For Barbara Johnson, there is, in fact, no final destination for Poe’s letter since, like any message, it is received every time it is read, however unintended the recipient: ‘[e]veryone who has held the letter – or even beheld it – including the narrator, has ended up having the letter addressed to him as its destination. The reader is comprehended by the letter: there is no place from which he can stand back and observe it … The letter’s destination is thus wherever it is read’.27 In terms of the militarised West as an open secret, this suggests that the condition of secrecy interpellates the reader, calling him or her into being as a function of that secrecy. Molczan has become so accomplished at finding the satellites, and the systems are sophisticated enough to know when they are being tracked, that satellites start to hide specifically from Molczan. Strangely, the democratic hobbyist here has not only addressed power’s hiddenness, but power has also shown itself to hide in response to that address. Wherever it is read, the letter has reached its destination. There is no outside the purloined landscape, but Molczan’s endless manoeuvring for position might stand as a model for the photographic project, shared by Goin, Misrach, Paglen and others, of showing the hidden in the act of hiding. Virilio’s assessment in 1991 that the revolution in military affairs had achieved ‘a gigantic making-over of facts’ through ‘a menacing blinding … of which everyone, civilian or military, is the potential victim’ is a democracy of sorts, one where everyone is equally blinded and dominated. Molczan’s retort to Virilio’s pessimistic assessment is to pursue Thomas Jefferson’s famous argument that the price of freedom is eternal vigilance, however hard it is to see the object under scrutiny. It is this commitment to ‘know[ing] what’s there’ that underwrites the photographic project of depicting the hidden, but as Poe’s story makes clear, this is never a straightforward process of revealing what has been concealed. It is through a redeployment of secrecy’s technologies of domination that the letter, and its menace, must be returned, interminably, to sender, folded inside out and back to front in endless refusal.