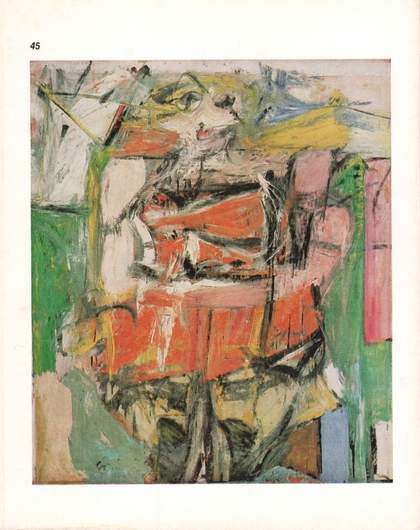

Fig.1

Cover of the catalogue for Two Decades of American Painting, 1967, showing Willem de Kooning’s Woman VI 1953

© Willem de Kooning Revocable Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In 1967, the travelling exhibition Two Decades of American Painting (hereafter Two Decades), coordinated and curated by the international program of the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA), toured to the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne (NGV) and the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney (AGNSW), having finished runs in Tokyo and New Delhi (fig.1).1 The exhibition was certainly important; a large number of artists and students active in Australia during the late 1960s visited the show, and it has become, for many aging baby-boomers in the Australian visual arts, an indelible memory.2 Indeed, Two Decades was one of the two most-remarked upon international exhibitions of contemporary art in the history of Australian art.3 But despite its enormous impact on the levels of public appreciation for contemporary art, the pop art and abstract works in the show were appearing belatedly, most of them too late to genuinely have an influence on advanced Australian artists’ practices, except at the level of measuring size and ambition. The world had already moved on, well beyond abstract expressionism and almost beyond pop art. Even so, the muteness of Ad Reinhardt’s ‘black square’ works, and Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup 1965 and Jackie 1964, carried considerable incendiary charge, offending conservative artists and public alike. The significance of the exhibition came not from an influential instance of cultural transfer, but from the fact that Two Decades was a watershed event at the end of one idea of Australian art and the start of another. Working with archival sources, the first part of this paper will provide an account of the exhibition’s Sydney and Melbourne instalments – their genesis, planning, events and finally their reception.

New York school painting and its associated criticism have been connected to Australia in terms of a transfer of influence from the cultural centre to the supposed ‘periphery’ of the art world; this forms part of a larger narrative that sees the ‘advancements’ of North American art disseminated to ‘provincial’ locations in large, revelatory exhibitions. In the second part of this paper, I will frame the exhibition differently, as one interaction in the shared transnational experience that had been marked by the proliferation of gestural abstraction and was now converging towards global conceptualism. In this, I draw largely on the conceptual framework of multiple international contemporaneities developed by Reiko Tomii in her ground-breaking 2016 account of ‘marginal’ or ‘peripheral’ art worlds in provincial 1960s Japan.4 I therefore wish both to downplay the narrative that the exhibition introduced artists to new art and to understand Two Decades within the framework of the idea of international contemporaneity. With this in mind, I explore the exhibition’s aftermath as a succession of contacts and resonances – as well as missed contacts – between New York and Australia, both of which were representative of the international contemporaneity that was then emerging. Revealing the contemporaneity to which I refer requires a bottom-up approach to local art histories, defying the outmoded tendency of North Atlantic art historians to expect to see derivative art elsewhere and to label it according to imported ideas of how art would develop, an idea which has been challenged in Australia by scholars of modern and postmodern art for well over a decade.5

Cosmopolitanism and Meadmore’s rolodex

This account of the genesis of Two Decades must first pay attention to the role played by the Cold War and US foreign policy in promoting American cultural activities overseas.6 MoMA had initiated its International Program in 1952 to export its exhibitions around the world, and the programme was strengthened from 1957 by sponsorship from the International Council, one of MoMA’s circles of benefactors.7 The Australian patron of the arts Lady Maie Casey, who was to open Two Decades in Melbourne, had become a MoMA International Council member well before the exhibition; her frequent contacts with MoMA dated from the tenure of her husband, Sir Richard Casey, as head of the Australian Embassy in Washington, D.C. in the early 1940s.8 During the 1950s and early 1960s, the US Information Service (USIS), which was part-coordinator of Two Decades, and MoMA’s International Council were indisputably linked to CIA personnel through cultural sponsorship aimed at projecting the prestige and power of American art.9 Such explanations for the genesis of Two Decades, however, would be incorrect. USIS and CIA sponsorship was trailing off by the time of the exhibition and in the end USIS had little involvement. It had managed the small exhibitions prepared by MoMA’s International Council that had arrived in Australia in the 1950s and 1960s, but these earlier exhibitions were far too humble to overwhelm home-grown culture; even the much-reduced British Council was more effective and thorough in projecting national prestige to Australia. So, against the Cold War grain of an exciting but over-easy assumption that there must have been masses of covert money behind Two Decades, it should be more plainly remembered that it was Australians who proposed that the exhibition travel to Australia, and who largely paid for it, only later being supplemented by American philanthropic largesse.

Two Decades was more the result of the cosmopolitanism of three internationalist individuals: the director of the NGV, Eric Westbrook; his exhibitions officer, John Stringer; and Daniel Thomas, an energetic young curator at the AGNSW. Without their cosmopolitanism, wide reading and peripatetic travel, this exhibition would not have been seen: they operated within a web of international contacts. A key intermediary was the Australian expatriate sculptor, the urbane Clement Meadmore, who had moved to New York in 1963. Although he rarely returned to Australia, he willingly shared his extensive New York address book with compatriots, providing introductions for the increasing number of Australians who were now making the pilgrimage to New York. In August 1964, Stringer visited New York and Meadmore urged him to persuade the NGV to tour a recent, landmark exhibition, Post Painterly Abstraction, curated by the critic Clement Greenberg. It was too late for this – the exhibition had already finished, the works had returned to their lenders, and in any case the costs would, it seemed, have been far too high for the NGV to bear. ‘But’, Stringer recalled, ‘fortune smiled and we ultimately did even better’.10 Meadmore threw a party to welcome Stringer to New York, and the young Australian curator found himself chatting to Greenberg, Jules Olitski and Barnett Newman, who in turn introduced him to Waldo Rasmussen, the Executive Director of Circulating Exhibitions for MoMA’s International Program. This, according to Stringer, was ‘a fortunate and timely connection that ultimately enabled the Gallery to snare his thrilling and authoritative Two Decades of American Painting direct from The Museum of Modern Art itself’.11

Next, Waldo Rasmussen found himself responding to a letter from Pamela Warrender, Chairperson of the Board of the small, precariously funded Museum of Modern Art and Design of Australia (MoMADA) that the patron John Reed had established in Melbourne. Rasmussen described to her an exhibition tentatively titled ‘Two Decades of American Painting’.12 The planning for the exhibition was already well advanced and Rasmussen was able to say there would be about one hundred paintings by thirty-five artists. It consisted of some key works from MoMA’s own collection but comprised a larger number sourced from other American art museums, a range of excellent private collections, art dealers, and directly from the artists. Many important works were, discreetly, available for sale. MoMA would put potential collectors or art museums in touch with dealers and the works could be acquired for what were, in retrospect, extraordinarily low prices. As the planning then stood, the show was to travel to the Japan Foundation in Tokyo in October 1966 and the Lalit Kala Akademi in New Delhi until April 1967. It might then conceivably be available for Melbourne in June 1967. Rasmussen’s letter detailed the costings and obligations of hosting the exhibition. He was very helpful, simultaneously writing to the American Embassy in Canberra and to the US Department of State, requesting sponsorship of the exhibition in Australia, even though he was unclear about where and what MoMADA was.13

Meanwhile, Warrender wrote a letter to the NGV to investigate the possibility of housing the exhibition, cheekily suggesting the NGV donate its own space, staff and resources to MoMADA for the show, and even collect and transfer to them the money from admissions and catalogue sales.14 But by the time Rasmussen next wrote to Stringer at the NGV, he had realised that MoMADA was not in any position to host the exhibition, and that the only practical option for sending it to Melbourne was to deal with Victoria’s principal state art museum, the NGV. This was now quite straightforward. As yet, however, Rasmussen had not had any formal expression of interest from the NGV.15 Rasmussen began his letter to Stringer by saying that he had met and spoken to Thomas, who he knew was a curator at AGNSW then visiting New York, and noted that Thomas hoped that Two Decades could also go to Sydney. He told Stringer that the exhibition could go to both Sydney and Melbourne only if it travelled from India or Japan by air, rather than by sea, because of the time constraints of loan agreements – many paintings were on loan from private collectors. The problem was further compounded by the size of some of the paintings, which were so large that they might not have fit in commercial aircraft and may have needed to be sent in military planes. It was clear that the exhibition needed the endorsement of both the US and the Australian governments. Westbrook replied enthusiastically on 5 August 1966, pointing out that MoMADA no longer had ‘any real existence’ and would be completely unable to host a show.16 He added that the NGV would need government assistance from the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board to meet the cost, and that this would be more likely to be forthcoming if the show also travelled to Sydney. His solution to the time constraint was to suggest that the Americans bring the exhibition straight to Australia from Japan, omitting the Indian venue. This was not something that MoMA were prepared to do.

‘Dear God, not the Poons!’

From here on negotiations took a far less tentative note and arrangements for the exhibition dates were quickly firmed up. Australia needed to find the money to pay for the tour, with the main sticking point being the cost of transport. The logjam was broken in December 1966 when American philanthropist Harold Mertz, who had recently formed a collection of contemporary Australian art to tour the United States, offered to underwrite this cost from his Mertz Art Fund.17 Two Decades, though, still presented the Japan Foundation and the Lalit Kala Akademi, and now NGV and AGNSW, with the logistics of transporting one hundred paintings from New York to Tokyo, New Delhi, Melbourne, Sydney and then back to New York within a tight schedule, all of which was necessary if the works were to be returned within the agreed loan period.

Fig.2

Installation view of Two Decades of American Painting at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1967, showing Barnett Newman’s The Third 1962

© Barnett Newman/ARS, New York

Photo © Geoff Parr

The largest painting was almost three and a half metres by seven metres, and some were approximately four and a half metres square. Barnett Newman’s The Third 1962 (fig.2), stood at two and half metres by three metres, which was a typical size for many of the works. They were thought to be far too large for normal commercial airfreight, which was why Rasmussen had sought military aircraft, but in the end the cost was far too high. Eventually, they were shipped by sea from India to Melbourne, by truck to Sydney, and then by Qantas flights from Sydney back to the US. No paintings were damaged until they reached India where the New Delhi galleries of the Lalit Kala Akademi proved to be less than ideal from a conservation point of view. Franz Kline’s Siegfried 1958 fell off the wall and was damaged. It was too large to be flown back to New York and so was sent on to Australia with the other paintings. The display spaces were not sealed off from the verdant gardens outside, and Adolph Gottlieb’s Pentaloid, Number 2 1963 and Ellsworth Kelly’s Orange Blue 1 1965 were both damaged by bird droppings inside the gallery. One crate (Case 23) was damaged during loading onto the ocean liner Oronsay in India for transportation to Melbourne. Rasmussen sent detailed instructions to Stringer about the handling of the paintings in a letter dated 19 May but there was more to come.18 When the exhibition was in transit back to New York from Sydney, crates containing three paintings were left out in tropical rain and heat in Brisbane by Qantas airfreight handlers. The damage included irreparable harm to Larry Poons’s delicate Richmond Ruckus 1964, with its thin, minimal, easily marked paint surface. Stringer wrote ‘Dear God, not the Poons!’ when he was informed of the catastrophe.19 Qantas paid for the damage.

It was clear at the time that MoMA primarily wished to send the exhibition to Japan and India, and in the context of the turbulent mid-1960s, it is obvious that there were powerful strategic and foreign-policy reasons why American cultural diplomacy to those nations mattered. From Kennedy’s presidency onwards the US had attempted to forge a closer relationship with India (the Russia-leaning leader of the non-aligned nations bloc at the United Nations); there was also still considerable anti-American feeling in the US’s closest East Asian ally, Japan. But even in India and Japan, both of which were more important to the US than Australia, local agencies had to find considerable sums of money to cover costs. Financial negotiations of this kind were and are normal among art museums and their overlords at ministries of culture. It is far from clear that Australia mattered enough – based on the correspondence between MoMA and American and Australian government agencies – for the Americans to have registered any pressing need to be involved in the expense of such costly cultural projection. Australia, after all, had been willingly involved in Vietnam since 1962. The Australians would have to pay for the exhibition themselves, and that was doubtful up to the last minute.20 The show therefore arrived more by lucky accident, individual curatorial persistence, newly available capabilities for airfreight and traditional North American philanthropy, rather than by US politico-cultural design.

‘The most important exhibition ever seen in Australia’?

Fig.3

Installation view of Two Decades of American Painting at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1967, showing Ad Reinhardt’s Abstract Painting 1960, Abstract Painting 1962 and Abstract Painting 1963

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2019

Photo © Geoff Parr

The Governor-General’s wife, Lady Casey, opened the exhibition in Melbourne with great pomp and ceremony on 6 June 1967. It was elegantly installed in the classically proportioned galleries of the great Victorian-era building on Swanston Street usually occupied by the NGV’s permanent collection, which had been moved out for the occasion. The grand nineteenth-century spaces suited the paintings, allowing them to be installed with plenty of space between them and framed by grand perspectives. The surroundings also gave their presentation a reverence and authority usually reserved in the NGV for old masterpieces, rather than more contemporary experiments. There were the expected howls of protest in the letters columns of the city’s newspapers: ‘Those art critics who pretend to rave over this collection are merely spinning elaborate phrases in describing something without meaning’, read one letter.21 Critical reception, however, was largely positive. The critics John Henshaw and Ronald Millar published equivocal but generally approving reviews and the young critic Patrick McCaughey wrote two impassioned, deeply complimentary reviews of the exhibition for the Age.22 So too did Daniel Thomas, who, on top of his curatorial position at AGNSW, was also the art critic for the Sydney Morning Herald.23 In an article published two days before the exhibition opened in Sydney, Thomas happily declared Two Decades to be ‘the most important exhibition ever seen in Australia’, commenting on the ‘enthusiasm and awe’ among the ‘fantastic traffic jams’ of people who had seen the exhibition in Melbourne. He then cut to the chase, addressing the main cause of popular complaint in many letters to the editors of Melbourne newspapers: three austere, almost blank, black-on-black paintings by Reinhardt: Abstract Painting 1960, Abstract Painting 1962 and Abstract Painting 1963 (fig.3). These were the most challenging, reductive works in the show, and turned out to be the ones that resounded most with young artists, as well being the most offensive works to some members of the public.

Fig.4

Installation view of Two Decades of American Painting at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1967, showing Andy Warhol’s Jackie 1964

© Andy Warhol/ARS, New York

Photo © Geoff Parr

Fig.5

Installation view of Two Decades of American Painting at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1967, showing Helen Frankenthaler’s Cape, (Provincetown) 1964

© Helen Frankenthaler/ARS, New York

Photo © Geoff Parr

The Ad Reinhardt paintings that Thomas wrote about were not for sale, but no Australian museum was brave enough to consider any of the other radical paintings. The works they passed up included: Warhol’s Electric Chairs 1964, which could have been acquired for US$6,065, and his Jackie 1964 (fig.4); Kline’s Shenandoah Wall 1961, which had an admittedly forbidding price tag of $100,000; Kelly’s Orange Blue 1 1965, priced at $3,200; Alex Katz’s then little-known paintings, such as Smile Again 1965, which was available for $3,560. In the end, the NGV and AGNSW both purchased easel-sized Josef Albers works from his series Homage to the Square. The NGV also acquired a much larger, important, landscape-like abstraction by Helen Frankenthaler, Cape (Provincetown) 1964 (fig.5); the AGNSW bought Morris Louis’s grand, austere but safely classic abstraction Ayin 1958. Louis’s and Frankenthaler’s stained paintings on unprimed cotton canvas had been the bridge to newer colour-field painters, and Greenberg had championed the work of both artists. Besides well-known paintings by Jackson Pollock, Jasper Johns, Newman and Warhol, also included in the exhibition was a major painting by Cy Twombly, who was then scarcely known. Rasmussen had to lobby very hard for the inclusion of now celebrated artists like Warhol and Twombly, who were still edgy at the time. The ever-prescient Thomas tried to interest AGNSW in more ambitious purchases and found out from Rasmussen that many more major works were potentially available than had previously been thought. He was not, however, able to act on this. Interest from private collectors was almost non-existent; with rare exceptions, the Australian art market was almost completely oriented around local names. The only notable private purchase was by the Sydney-based modernist architect Harry Seidler of another of Albers’s Homage to the Square works.

Visitors queued in Melbourne winter rain and the NGV extended its opening hours. Two Decades attracted a staggering number of visitors for a public exhibition in 1967 – 115,000 visitors in Sydney alone. These were numbers consistent with the success of later imported blockbuster shows of modern and contemporary art, a sequence of which followed. For though MoMA itself was becoming increasingly detached from contemporary art, the succession of exhibitions that reached Australia from the museum’s International Program – Two Decades in 1967, Surrealism in 1972, Some Recent American Art in 1974 and Modern Masters: Manet to Matisse in 1975 – gave Australian audiences unprecedented access to major works of hitherto unseen international art.

Two Decades was a carefully selected touring exhibition, assembled by MoMA from many well-known and important lenders. It was not merely part of a collection exported during an institution’s downtime. It was a substantial exhibition but, even so, was disconnected from any discourse of the time about contemporary art, containing no new thesis about its art at all. The catalogue allocated a double-page spread for each artist, consisting of illustrations facing a checklist and a short biography. There were three very short essays. The first, by young art historian Irving Sandler, foreshadowed the tone of his landmark book The Triumph of American Painting, which was to be published three years later.24 It concentrated on abstract expressionists and colour field painters, enthusiastically echoing the then virtually hegemonic taste of Greenberg. Through Rasmussen, Greenberg offered to come out to Australia for a speaking tour associated with the exhibition, but his demands for a first-class air ticket and considerable fees far exceeded the Australian budget and he was turned down.25

The second essay was by Lucy Lippard, about to become a pioneering promoter of feminist and post-minimalist art. Her focus was on the rather restrained minimalist component of the exhibition, represented by Ad Reinhardt and Frank Stella. Since it was an exhibition of paintings, there was nothing by minimalist sculptors Donald Judd or Dan Flavin, nor anything by any of the other, already famous, more conceptual minimalists such as Carl Andre or Sol LeWitt. Judd, Flavin, Andre and LeWitt were all featured in the follow-up exhibition, Some Recent American Art, which toured to Australia in 1974. The third essay for Two Decades, principally on pop artists James Rosenquist and Robert Rauschenberg, was by maverick critic Gene Swenson, a tireless promoter of pop art who had been working freelance at MoMA for a couple of years on special exhibitions.

The appearance of contemporaneity

When Two Decades appeared in Melbourne and Sydney, the ‘moment’ of the art it featured was already past, even if its ambition was not. The hopes Daniel Thomas expressed in his review regarding the far-reaching benefits the show might have for painting in Australia were anachronistic.26 Since the works belonged to the recent but rapidly receding past, they were ultimately irrelevant in the creation or diffusion of new art. Epochal though the works in the exhibition were, and though the exhibition was widely visited by Australian artists, by mid-1967 the circles of ambitious young artists who were to centre around Pinacotheca Gallery in Melbourne and Central Street Gallery in Sydney were already moving past these received influences, forming their own, tight-knit groups whose art was contemporary and not at all belated.

In her ground-breaking 2016 account of ‘marginal’ or ‘peripheral’ art worlds in provincial 1960s Japan, Radicalism in the Wilderness, Reiko Tomii elaborates the art historical idea of multiple appearances of contemporaneity.27 Tomii eloquently sets out the same problems that historians of Australian art face, including that of revising accepted wisdom. She goes on to explain that making a simple acknowledgement that a local artist’s practice is pioneering, and then arguing that it should be added to a global list of key artists, is inadequate. In the mid-1960s and well into the 1970s, Americans saw the proliferation of gestural abstraction as the triumph of North American painting whereas others saw it as a shared transnational experience. In fact, Tomii suggests, we might think of abstract expressionism as one local manifestation of gestural painting.28 She asks how we can create transnational art histories that bridge the inevitable silo of national art history, connecting the local to the global.29

As Tomii points out, the caveat is that although such a framework can be global in its ‘resonances’, Australian artists and writers largely ‘connected’ with North Atlantic art and art writing in practice in their lived writerly and artistic experience, though not exclusively.30 The US and Europe, in other words, constituted their principal frame of reference and the benchmarks against which they measured themselves. So, in Australia as in Japan, Tomii argues, ‘neither the perception nor the reality of “center-periphery hegemony” ever disappeared’, even though Bernard Smith had attempted in the latter pages of his foundational text, Australian Painting, 1788–1960, to formulate an alternative – a complex hybrid of regionalism and two-way centre-periphery diffusion.31 On the other hand, as I have shown in my work with Anthony Gardner in Biennials, Triennials and Documenta (2016), curators also consciously created Third World and then pan-Asian networks from 1955 onwards.32

I am insisting on the contemporaneousness of art made in the provincial centres of Melbourne and Sydney compared with the equivalent provincialism of the city that was then the transatlantic art world’s largest centre, New York. A vastly larger art world province than Sydney or Melbourne, New York was supercharged in its pretensions to universalism courtesy of the Cold War and its unbroken projections of North American economic and political might. But from the late 1960s, Australian art became contemporaneous with North American and European art – as did art in Japan, Eastern Europe and South America – with work as innovative and significant as anything in New York then being produced. Until recently, this has not been recognised and, at the time, indifference was mistaken for provinciality.

Waldo Rasmussen flew to Australia for Two Decades’s Melbourne opening and then travelled to Sydney. He wanted to collect an archive of Australian art for MoMA’s reference library and was also interested in acquiring works for the collection. In Melbourne, John Stringer took Rasmussen to visit several artists, most of whom were about to be associated with charismatic art dealer Bruce Pollard’s avant-garde gallery, Pinacotheca. Through Stringer, Rasmussen was able to see the impressive, early, oddly shaped minimalist works of Trevor Vickers and Paul Partos in their inner-city studios. In Sydney, Daniel Thomas took Rasmussen to visit several galleries – notably Central Street Gallery and Watters – and artists’ studios. They spent three days looking at paintings, sculptures and architecture across the city and its inner suburbs. The artists Rasmussen visited with Stringer and Thomas were featured in Melbourne the following year in The Field, curated by NGV Curator of Australian Art Brian Finemore along with Stringer, which was the inaugural exhibition at the NGV’s new premises on St Kilda Road.33 These artists’ austere aesthetic, at that point beginning to incorporate shaped and modular formats, had already moved past most of the works in Two Decades.

Although letters between Stringer and Rasmussen show that these visits were stimulating and that the US curator was deeply impressed, they did not add up to much in terms of concrete outcomes. Stringer’s career, however, blossomed, and he moved to New York in 1970 to take up a position at MoMA as Rasmussen’s assistant director for the International Program. Otherwise, the lack of Australian follow-up and the generally apathetic attitude of many Australian artists and their dealers to Rasmussen’s attention is striking. Rasmussen wrote to Stringer in Melbourne and Thomas in Sydney in October, nearly five months after his June visit, asking for slides of artists’ works as they had arranged:

I’m anxious to report to a curatorial committee in the museum on work by Australian artists in the early part of November, and I still haven’t received any from Sweeney Reed of [Col] Jordan, [Ken] Reinhard and [Sydney] Ball, nor gotten any from Robert Jacks … I’m afraid my report will lose its point if I can’t show the material soon.34

None were supplied. Incidences such as this might lead us to doubt those confident assessments that trumpeted the impact of Two Decades, let alone any scandal.35 John Stringer’s perhaps unexpectedly sceptical recollection of the exhibition’s impact, as he raced through his studio visits and selection for The Field the following year, is worth quoting:

While the more informed were generally impressed and very supportive of the exhibition, far more significantly, the young found they had an unprecedented opportunity to pass judgement on the entire preceding generation of painters.36

But the artists themselves were already – casually, but nonetheless insistently – aware of their own contemporaneity. Robert Hunter was escaping colour field painting via a highly original fusion of decoration and austere minimalism in white-on-white, repetitive grids (and then masking-tape, gridded geometries applied direct to gallery walls) that his international peers recognised immediately. Rasmussen, who continued in his position at MoMA with international exhibitions well into the 1990s, directed the US participation with Robert Ryman, Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt in the 1970 Delhi Trienniale-India. It was here that Hunter, representing Australia, met Andre. The two became good friends and Andre helped Hunter to have his breakthrough works shown in New York. London-based expatriate conceptualists including Ian Burn and Mel Ramsden were fiercely dismissing both abstraction and minimalism as old fashioned and irrelevant, having already arrived at their conceptualism before their friends at home ever bought bright acrylics, masking tape and unprimed cotton canvas. The incompatibility of subsuming such different practices into a coherent national Australian art was not very clear in 1967, not even to energetic curators such as John Stringer. For different, hard-to-decipher strands – aesthetic, critical, historical – underlay new Australian art, which both differed from and intersected with American art of that exact moment.

Contrary to the image projected by the glamorous, impeccably installed exhibition and press fervour, the prestige of American painting was already exhausted under the weight of the already anachronistic dogma of formalism. Stringer himself was always careful to point this out. His example was Melbourne painter Janet Dawson who, Stringer remembered, was ‘one of Melbourne’s most respected progressive artists,’ but who ‘had already abandoned her brief flirtation with hard edge painting prior to the advent of Two Decades of American Art’.37 Trevor Vickers and Paul Partos, who were among the artists Rasmussen visited with Stringer, were both making monumental paintings that edged through minimalism, a style that had been profoundly hostile, from the moment of its appearance in New York with Donald Judd and his art criticism, to Clement Greenberg’s idea of colour field painting. This incompatibility was lost on local art critics. Although Vickers had been one of the first Melbourne colour field artists, he was moving beyond his earlier works to large, modular constructions, incorporating irregular shapes and voids, but smothered in thick, glossy, viscous acrylic paint and resins; paintings by Peter Booth also had similar surface effects.

The young Sydney art critic Terry Smith was at this moment beginning to formulate a powerful case for this art’s contemporaneity. This would become his essay, ‘Color-Form Painting: Sydney 1965–1970’, which remains key to understanding the art of the period and was among the first instances of art history written on contemporary art and art criticism in Australia with a historiographical self-consciousness.38 Smith’s argument was that painting made in Sydney between 1966 and 1970 by artists associated with the Central Street Gallery constituted an innovation that he called ‘Color-Form Painting’. Furthermore, he proposed that the Central Street Gallery group constituted an Australian avant-garde. The artists he mentioned by name were Tony McGillick, Rollin Schlicht, Royston Harpur, Gunter Christmann, Dick Watkins and Joe Szabo. He omitted the artists of the Pinacotheca group in Melbourne – Dale Hickey, Robert Hunter, Trevor Vickers, Peter Booth – whose works he was not as familiar with. Arguably, in the case of Robert Hunter’s paintings on paper and ephemeral paintings made directly onto walls, Trevor Vickers’s modular, fibreglass resin polyptychs and Dale Hickey’s translations of painting into ready-made installations, they were just as relevant to Smith’s thesis. The task remains to embed all these artists – especially McGillick and Hunter – within an international canon of contemporary art history alongside the several other important developments in painting outside New York’s and Artforum’s purview, including the French Support-Surface group.

Two Decades was, at first sight, a simple example of cultural transfer from centre to periphery. I have been arguing that the truth was more complex. Younger Australian critics – including Terry Smith – understood that this new American painting, demanding the removal of subject, content and emotion, contained nothing that made it obviously either provincial or metropolitan. The Central Street Gallery and Pinacotheca Gallery artists saw the unique advantages of such a stripped down language, such elimination of local signifiers, and according to Smith ‘they believed that their kind of painting had only to be shown and it would convert the Sydney art world’.39 But the project failed to produce art that was internationally successful, apart from Melbourne painter Robert Hunter’s minimalist wall drawings at the Delhi Triennale-India and then his participation in curator Jennifer Licht’s group exhibition at MoMA. Indeed, Smith was underwhelmed rather than confirmed in his analysis by the apparently indiscriminate proliferation ‘as style’ of such art in The Field, a mere year later. This was driven home by Greenberg’s disappointing indifference to the work of the Central Street artists when he visited Sydney in 1968.40 The same was true in Melbourne. Terry Smith called Greenberg’s response a ‘pin-prick’ but it must have been a disappointment for the ambitious Central Street artists, whom Smith argued had developed a strategy that they hoped would enable them to break into the international art world.41 Not only that, but Greenberg’s visit should have been the perfect opportunity for at least one of them to be picked up and swept off to international art world stardom, as had the Canadian Jack Bush, or even for regional US artists like Morris Louis and Anne Truitt, both of whose careers were transformed by visits to Washington, D.C. from a younger and less jaded Greenberg.

Conclusion

Two Decades was an exhibition important for what its reception demonstrated: Australian art had arrived at a watershed. This is why the exhibition is remembered with such intensity – one world was fading and another was emerging into focus. Two Decades appeared within the broader political and social context of the Cold War, the Vietnam War and worldwide anti-American feeling, as well as protests against Australia’s longstanding, deeply conservative state and federal governments. Making and understanding Australian art as ‘regional’ art – landscape or Antipodean-style allegorical figuration – was an exhausted and now reactionary tradition. Leftist, social realist artists despised the exhibition, such as Noel Counihan who deplored its ‘dehumanised values’.42 A range of artists, from Herbert McClintock (‘It is contempt. Contempt for the cultural achievements of mankind’) and Rod Shaw (‘I find it disturbing to see human beings gazing at Reinhardt’s black squares with reverence and awe, as if a prophet had emerged’) to neo-Romantic Francis Lymburner (‘Utterly boring. Complete rubbish … I think it has no relevance whatever for Australian art’) all lamented the absence of a recognisable, sympathetic humanism in Reinhardt, Alan D’Arcangelo, James Rosenquist, Larry Rivers and Katz.43

Fig.6

Back cover of the catalogue for Two Decades of American Painting, 1970

This had been Smith’s lament in Australian Painting, his famous account of Australian art. But they all failed to see that the superficially distinctive, landscape–figure themes of Arthur Boyd and Sidney Nolan – of self-consciously national contemporary art – represented only one stream of Australian art and neither this, nor its 1940s antagonists, any longer compelled innovative artists. This failure, rather than philistinism, was why older artists and writers on art were so suspicious of the imaginary excesses of a great exhibition of already dated but indisputably epochal American painting.

Contemporaneity had arrived in Australian art, more or less at the same time as it was arriving in New York, just as the sombre humanism of Two Decades’s abstract expressionism and the apparent cynicism of its pop art masterpieces (with their pathos invisible to older critics and artists) was itself already under attack from yet more advanced artists both in New York and in Melbourne and Sydney. Two Decades of American Painting was less a catalysing event for Australian art than, in its polarised or else strangely casual reception, the demonstration of the passing of the idea of Australian art itself, and thus a watershed moment.