John Baldessari

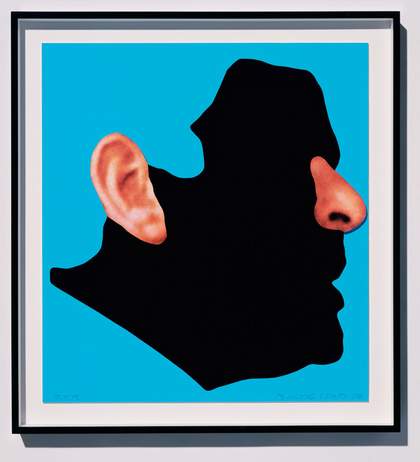

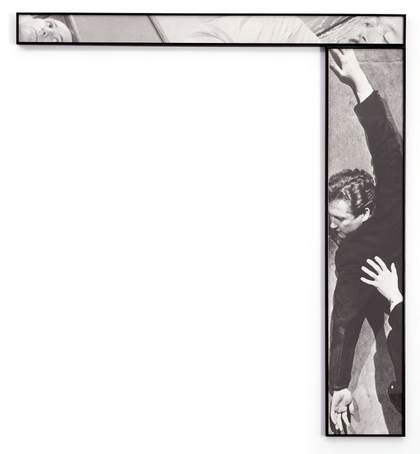

Two Voided Blocks 1990

Black-and-white photographs, vinyl paint

157 x 245 cm each

Courtesy 2009 John Baldessari Studio © John Baldessari

Jessica Morgan

You grew up in America as the son of immigrants, an Austrian father and Danish mother. To what extent were you influenced by your parental background?

John Baldessari

I certainly noticed that my parents were different from my friends’ parents. We ate different food, for a start. My mother was very health-conscious and made all sorts of healthy things, such as brown bread, yoghurt and tomato juice with yeast in it. I remember drinking a tea made of alfalfa and thinking: ‘Why can’t I have Lipton’s like my friends do?’ I was born at the end of the Great Depression, and my parents had become totally self-sufficient. They grew all their fruits and vegetables, had rabbits and chickens and made their own wine. We would fill five-gallon water bottles with spring water every Sunday. There was a huge compost pit, long before anybody else had one. My mother and father came from different social backgrounds. My mother was middle class, and my father had grown up with eleven brothers and sisters in a house where the family lived up top and the livestock below. He left as soon as he could cobble together some money for a passage to America.

John Baldessari

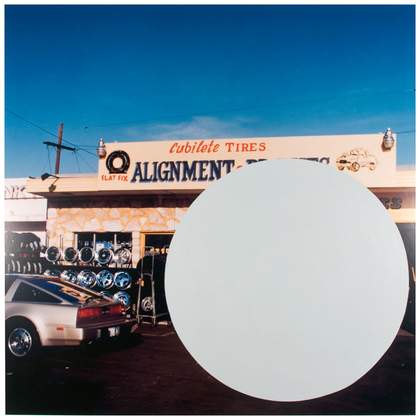

National City (w,1,2,3,4,5,6,B) D details – 2 and 3 (1996–2009)

Colour photographs with acrylic paint

46 x 46 cm

Courtesy 2009 John Baldessari Studio © John Baldessari

John Baldessari

National City (w,1,2,3,4,5,6,B) D details – 2 and 3 (1996–2009)

Colour photographs with acrylic paint

46 x4 6 cm

Courtesy 2009 John Baldessari Studio © John Baldessari

Jessica Morgan

He was the only one who left?

John Baldessari

Yeah. All the other brothers were killed in the war.

Jessica Morgan

And how did he meet your mother?

John Baldessari

That’s a mystery. He must have been a charmer though. He worked for a while in a Colorado coal mine, and made extra money picking up cigarette ends, breaking them open, re-rolling them and selling them. Somehow he got to California, where my mother was working as a private nurse. He had a restaurant for a while, but soon moved into the salvage business. He would tear down houses and recycle all the materials. I remember I would help out – taking nails out of lumber. He got enough money to buy a building site, and then he would use that stuff to build a house and buy what new materials he had to. He’d sell that and then keep on going. He was an entrepreneur, a self-made man. Near the end of his life he had enough to build a movie theatre, an office building…

Jessica Morgan

The movie theatre that used to be your studio? The one I have seen pictures of stacked with paintings?

John Baldessari

Yes, that was my studio after the theatre became vacant.

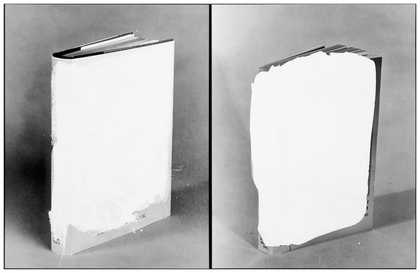

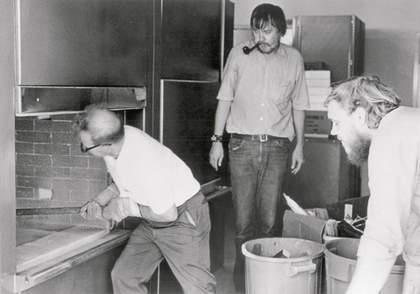

John Baldessari's studio with work displayed for the last time before burning in Cremation Project in 1970

John Baldessari (centre) overseeing Cremation Project !970

Jessica Morgan

Was there any art in your parents’ house?

John Baldessari

We had one painting, which was a bad copy of Caravaggio’s Boy with a Basket of Fruit c.1593. However, my mother was insistent on culture, so my sister and I took piano lessons. I get my love of classical music from that.

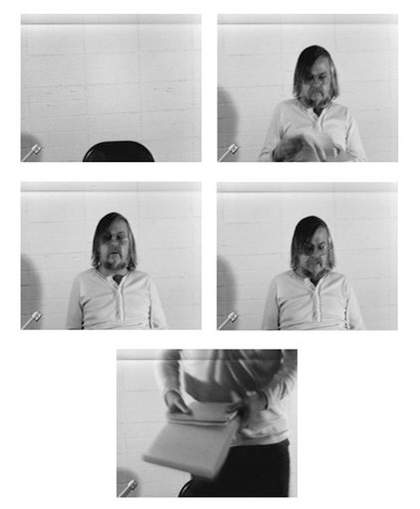

John Baldessari

Stills from Baldessari Sings LeWitt 1972

Black-and-white video, sound, 15 min

Courtesy 2009 John Baldessari Studio/New Art Trust, San Francisco © John Baldessari

Jessica Morgan

You also have a strong interest in literature, and language and words feature strongly in your work. Where did that come from?

John Baldessari

My mother would have novels sent to her from Denmark. I remember the feel of the book – the way you had to slice open the pages. I got a real love of books that way. They were all in Danish, of course. My father’s attitude was different. He would say: ‘Why are you spending all your money on buying books, I can get them for you for ten cents apiece.’ He could barely get through reading the newspaper at night.

Jessica Morgan

Was there a difference linguistically?

John Baldessari

Her English was quite good, but his was not so good, even later in life.

Jessica Morgan

Do you think those two elements affected the way you read language, or the way you used language in your work?

John Baldessari

Well, no, but it is a good point. I think something that got into my system was having to explain things to my father because of the language barrier. I’d try one way, and if that didn’t work, I’d try another. It was a strange experience. Certainly, I have used the same method in my art and in my teaching.

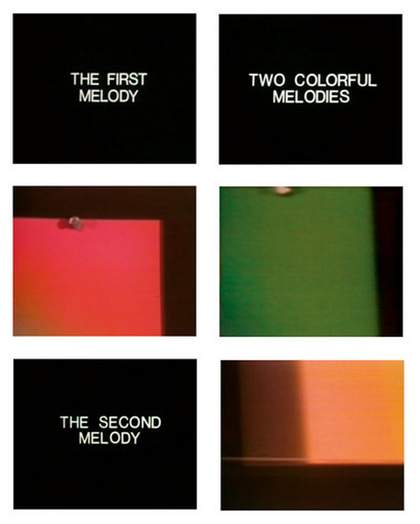

John Baldessari

Stills from Two Colourful Melodies 1977

Colour video, sound, 5.30 min

Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix © John Baldessari

Jessica Morgan

What were your first influences in art? Did you have any pre-school training?

John Baldessari

No. National City was such a poor area. I took art classes – pastels, watercolours of flowers. I guess I was good, because there was something called the National Scholastic Art Award in the US, and my art teacher encouraged me to enter. At that time I was experimenting with photography, so I put in a photograph, and I won. That’s where it all began. My father’s response was: ‘Oh that’s nice, did you make any money?’ He wasn’t mean-spirited; for him it was about survival.

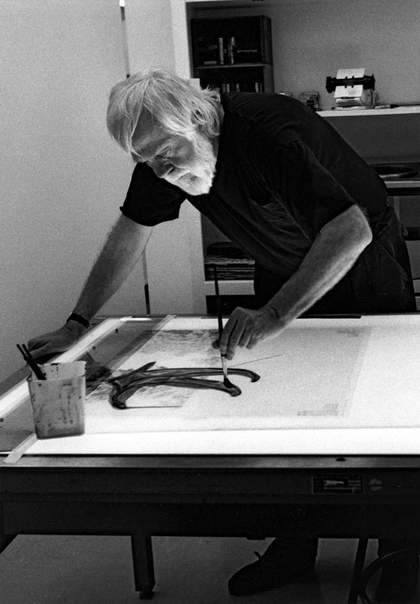

Sidney B. Felsen

John Baldessari in his studio 1992

Photograph

Courtesy 2009 John Baldessari Studio © John Baldessari

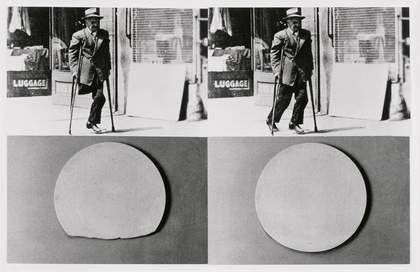

John Baldessari

Repair/Retouch Series: An Allegory About Wholeness (Plate and Man with Crutches) 1976

Four black-and-white photographs, mounted on board

38.1 x 61 cm

Courtesy 2009 John Baldessari Studio © John Baldessari

Jessica Morgan

So when were you first aware of art and the history of art?

John Baldessari

My sister encouraged me to go to San Diego State College, so I went there in 1949. I nearly chose to major in chemistry as I really liked the subject, but I decided to study art instead. I didn’t have a clue about art history. I didn’t know anything about Picasso or Matisse. I remember seeing Matisse in a history of art course for the first time, and I was appalled and said so to my instructor. He said, well I bet in a year you really like him. He was right. In a year I was copying him.

Jessica Morgan

How was the teaching then?

John Baldessari

They were teachers first and artists second. I had this one instructor I liked a lot who seemed to be serious about painting. He suggested I submit a slide to a local competition – and I got in. That’s where I got my first review. The LA Times critic said mine was one of the best paintings. Later, in 1954, I enrolled in summer classes at UCLA, where the star attraction was the hot LA artist of the time called Rico Lebrun – a Neapolitan who had moved to America. He seemed like a real artist. He would come over to see my painting, always bringing a visitor – one time it was the composer Lucas Foss, another it was the painter Bill Bryce. Lebrun gave a weekly public lecture. The last one he gave was all about my work, which really surprised me. Afterwards, he asked if I had thought about being an artist. I said I hadn’t. He then advised me to enrol at the Jepson Art Institute run by his friend Herb Jepson – it became the Otis Art Institute. I was there from 1957 to 1959. It was a very traditional place where you drew or sculpted from the model. When I was there I entered another competition in Los Angeles. The LA Times said about my drawings: ‘It’s nice to see that somebody in Los Angeles can draw.’ I thought, okay, now I don’t need to draw any more, so I gave that up and got a teaching job.

Jessica Morgan

At this point you were still teaching high school?

John Baldessari

The period for me was good because I was isolated from any influences of Los Angeles, although I would make monthly treks to look at shows. I kept applying for college teaching jobs and getting rejected. So it just became clear to me that I would continue teaching high school. I knew I would make my father happy if I got married and had children. That’s all he cared about. I was trying to find out in a Cartesian way, I suppose, what art really was at some ground level, so a lot of my early work was about that. But I got tired of people saying my kid can do that, and I decided, well, why not just use language, why not use words.

Jessica Morgan

Was there anything that you’d seen containing text that interested you?

John Baldessari

Yeah, certainly Braque, Picasso and Lichtenstein.

John Baldessari

Man Fallen In S-Curve (With Man Looking Down And Man Looking Up) 1984

Black-and-white photographs

122 x 132 cm

Courtesy 2009 John Baldessari Studio © John Baldessari

Jessica Morgan

How did you make the leap to teaching at art school?

John Baldessari

My big break in my life came when the University of California decided to open a campus in San Diego. One of my part-time jobs was at the UCLA extension, as it was called, and I got to know Paul Brach, who was chosen to be the chairperson of the new art department. We hit it off – he has a bad sense of humour like mine. One day he called me and said would you teach in my faculty two days a week, I’ll give you a studio and I’ll give you more salary than you’re getting now. I said, whoa, of course I will.

Jessica Morgan

At this point in the early 1970s you were making the text and photo works. Where does the text come from?

John Baldessari

It is all found text, although now and then I might change a word. I would take the idea to local sign painters and give them instructions. I would say: don’t try to make it decorative. I got them to use all the colours that I liked – so some are grey, some are kind of icky pale green, pink, or yellow.

Jessica Morgan

In 1970 you made a radical gesture – you cremated most of your paintings. Why did you do that?

John Baldessari

Well, you said you’d seen photographs of this movie theatre full of paintings. I was drowning, inundated by paintings. I was getting more and more doubtful that only painting was art. The fun of it was doing it, and I thought I don’t really have to own these things, nobody’s ever going to buy them. And I had a slide record of everything… One of my first ideas – which may have come out of watching too many Bond movies – was to photograph each one and make it into a microdot. I would put them under stamps and mail them to friends, but that seemed too labour intensive. Then I thought about the idea of my work as a cycle – an eternal return – so all these materials, pigments and canvas that came out of the ground would return to it. It was a body of work, and I said what if these works are me, and so I’ll cremate them literally as a body. I found a crematorium that would do it. The guy that did the actual cremating studied art and was really into the idea. We had nine and a half boxes filled with the ashes of my work.

Jessica Morgan

Around this time you made a series of video works which have now become iconic pieces – such as I Am Making Art 1971, where you make very simple movements with your body; Baldessari Sings LeWitt 1972, in which you put Sol LeWitt’s theoretical reflections on art to music; and Teaching a Plant the Alphabet 1972.

John Baldessari

Yeah. By that time I was teaching at the Californian Institute of Arts (CalArts). The Sony Portapak had come out and at CalArts we had 26 of them. Can you believe that? So every artist started making videos.

Jessica Morgan

Your choice of subject matter seemed like a spoof on other artists.

John Baldessari

I would make these videos on a Sunday, and they were meant just for me and my students.

Jessica Morgan

They made very conscious references to the art of the time though…

John Baldessari

I thought conceptual art at that time was too pedantic. There were many ways artists used language, so why not try some other way? I was, of course, aware of the idea that an artist makes choices – if I made any little body movement in I Am Making Art, that was a choice, so I’d just made art. I love pushing things to their logical extreme, which at some point becomes ridiculous if you go with it far enough. Teaching a Plant the Alphabet was done during the hippy times. There were books about how to communicate with your plants. I thought, okay, I guess’ll start with the alphabet and then we’ll talk…

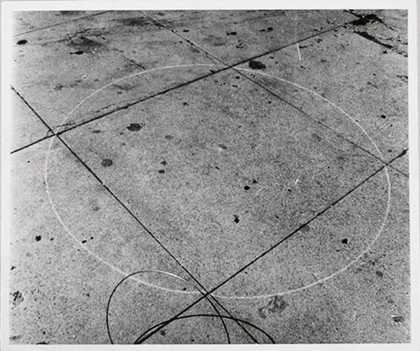

John Baldessari

Trying to Roll a Hoop in a Perfect Circle (Best Sequence 216 Frames) 1972–3

Nine black-and-white photographs and pencil

Details – 1 of 9, 12.7 x 15.2 cm

Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and Paris © John Baldessari

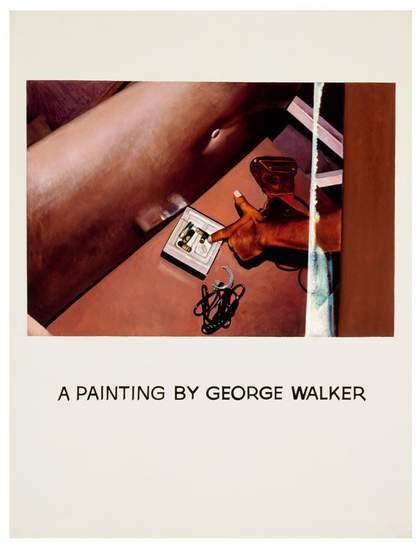

John Baldessari

Commissioned Painting: A Painting by George Walker 1969

Oil and acrylic on canvas

150.5 x 115.6 cm

Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery © John Baldessari

Jessica Morgan|

How did the Commissioned Paintings come about?

John Baldessari

David Antin and I both had a fondness for amateur art. I felt that art didn’t have to be about the touch of the artist, you could be an art director, or strategist – so why not just commission some of these amateur artists to paint my work? I had seen their pictures – Mexicans asleep under a cactus; a ship in moonlight – at the county fairs that my father used to take me to. I decided to give them new subject matter. At the time I was doing this other project with a friend walking around pointing to things in a visual field that caught his attention, so I combined the two ideas. I went to the Sunday painters with a dozen or so slides and said: ‘Listen, I’ll pay you X amount of dollars to paint this. I don’t want you to make art out of it, just render the slide as faithfully as you know how on the canvas.’ I would give them the canvas with the area masked out and they painted it.

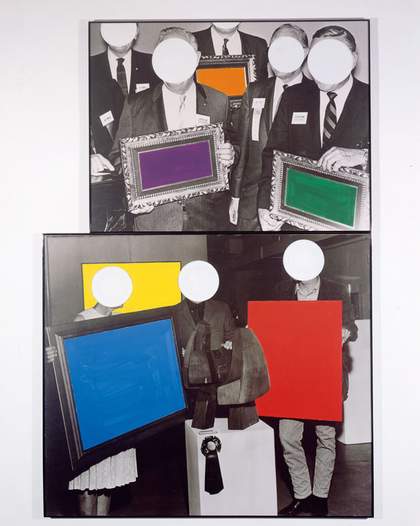

John Baldessari

Frames and Ribbon 1988

Black-and-white photographs and vinyl paint

213.6 x 142.2 cm

Courtesy Simon Lee Gallery, London, and L&M Arts, New York © John Baldessari

Jessica Morgan

Around this time you started to introduce appropriated photography into your work? What led you to use these images?

John Baldessari

I was trying to be artless. I thought the more I’m involved with art, the more artful I’m becoming, so how do I get myself out of that? Well, have other people do things for me, or just use other people’s imaging.

Jessica Morgan

How did you develop the idea of making works out of multiple photographs?

John Baldessari

It was very simple. Nikon had launched a camera with a motor so you could do sequences of photographs. At the time I was making work with video and film, but I had a little epiphany on a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I saw the paintings hung down the wall, and I realised they looked like a strip of film. So if a van Gogh painting was one frame, what would the frame before or after that be like? I was thinking art photographically. My early videos and films looked like still photography, and my still photography looked like films. But then I also began to think that central to life is not stasis but flux. I didn’t want to be a kinetic sculptor, but I thought somehow the idea of movement should be addressed.

Jessica Morgan

Much of your appropriated photography is not contemporary. Why is that?

John Baldessari

Because the pictures were cheap at the time. What I discovered about images from the movies – and this was only afterwards – was that people carry them around in their head. Sometimes they even control the person’s behaviour. I can use that image bank that people have and begin to tweak it and change the meaning. I suppose if I had an image bank of more recent stuff, I would do the same thing. For a while I had a guy working in a movie house and he was giving me stuff. Some of those photographers back then… they were really good at doing production stills.

John Baldessari

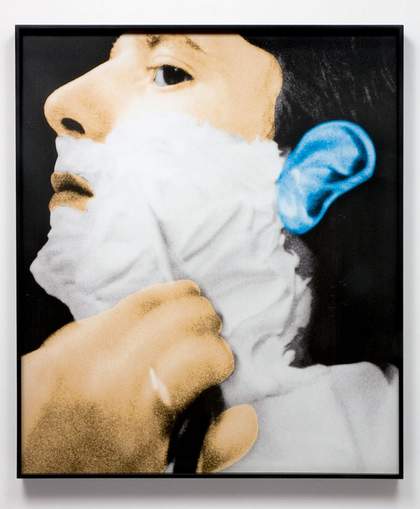

Noses and Ears, Etc (Part Three): Altered Person Being Shaved 2007

Archival inkjet print mounted on Sintra

128.9 x 110.5 x 7.6 cm

Courtesy 2009 John Baldessari Studio © John Baldessari

Jessica Morgan

To what extent do you think the process of your work is reflected back into your teaching – and vice versa?

John Baldessari

One seems to mirror the other, which is something that started with trying to make things clear with my father. I think that even if I have an audience of one, art is about having somebody to talk to.