David Noonan

Untitled 2009

Screenprint on linen

62 x 44 cm

Courtesy Hotel © David Noonan

On a drowsy English afternoon, in his bedroom in an old country house, a small boy called Kay Harker is pondering the whereabouts of a treasure hoard, property of his ancestors, now missing, presumed stolen. In the stillness, and by daylight, the fixtures and fittings of the room are less frightening: the hearthstone, for example, beneath which the bones of a murdered man are supposed to lie; or the highwayman’s pistols, wired to the wall; or the wainscoting in which, at night, additional doors appear. The boy is then taken by magic to a neighbouring estate, and to the upstairs corridor of another remote country mansion, as somnambulant in the afternoon quiet as his own. Here, in a clearly ceremonial but plain room, a Head (for that is its name) is being conjured by necromancy to answer questions – subject, treasure – by a sinister gentleman magician, name of Abner Brown. The Head stands on a pedestal, part a piece of occult technology, part Modern Movement robot, and speaks in a thin metallic voice. Abner, senior in his coven, is also a gangster.

Such is an episode in John Masefield’s richly poetic novel for children, The Midnight Folk, first published by Heinemann in 1927. The story weaves magic through the manners and landscape of the English county families of the Jazz Age: talking cats, a loquacious fox with the cheery humour of a bachelor sportsman; family portraits as portals to the past; gatherings of witches in the dining room, uproariously carolling (“Chorus, dear Sisters please…”) their equivalent of an old school song: “When midnight chimes in the belfry dark, and the white goose quails at the fox’s bark, we mount the horse that is hoofless…”

There is an intensity of atmosphere and imagination to Masefield’s writings for children which derives as much from the quietude of deserted places – a derelict and overgrown stables on a summer afternoon, for example, or the dry and undisturbed coverts of a private, seldom visited wood – as it does from descriptions of active and operational magic. As a poet, foremost, Masefield evoked a heady confluence of time and place, nature and the supernatural, through which agents of good and evil, past and present, could concentrate on their appointed rounds. This was a particularly English notion of the occult, the patterning of which also runs deep across certain twilit corners of twentieth-century British art: that magic is related to the spirit of place as much as to sigils and spells, and to the imprints on landscape of earlier rites and rituals, and the slipstream of spirits and enchantment. Twenty years earlier, the Bloomsbury novelist E.M. Forster had employed such notions of magic in successive works of fiction. He was interested in the relationship between emotional honesty and cosmic destiny, as it concerned the manners and social conventions of the English middle and upper middle classes in the years preceding the First World War. His first love, as a scholar, being a kind of Cantabrian Anglo-Hellenism, the device most frequently used – despite occasional side steps into pure fantasy – was that of landscape as a theatre of destiny, with direction supplied by barely glimpsed but alert and deeply felt spirit activity.

Journey to Avebury 1971

Super 8 mm blown up to 16 mm

Film still

Courtesy James Mackay © The Estate of Derek Jarman

Derek Jarman

Journey to Avebury 1971

Super 8 mm blown up to 16 mm

Film still

Courtesy James Mackay © The Estate of Derek Jarman

In his novel The Longest Journey of 1907, for example, Forster takes a vexed constellation of his principal characters to a (fictional) ancient site in the Wiltshire countryside: Cadford Rings – two grown over concentric circles of entrenchments, within which stands a single tree. It is within the psychic force field of this place that one character is presented with traumatising information about himself, which will subsequently shape his destiny. With his customary technique of clothing matters of the highest spiritual importance in the language of domestic familiarity, this fundamental shift in the novel’s tragic course is marked solely by one line, delivered by Mrs Failing with ominous sweetness: “This place is full of ghosties… Have you seen any yet?”

In Forster’s concept of the occult and the supernatural, there is much that can be recognised of the later exploration of such themes by British artists during the first half of the twentieth century. Above all, there is a deeply intimate relationship with landscape as an historical accumulation – with the geological materiality of the land, as well as with the sacred and religious structures and totems of early (and earliest) settlers. And within this relationship there is a sense of the modern quotidian running parallel with, and at times overlapping, the presence of the supernatural and the paranormal. Forster’s description of Cadford Rings is exemplary in this respect:

The Rings were curious rather than impressive. Neither embankment was over twelve feet high, and the grass on them had not the exquisite green of Old Sarum, but was grey and wiry… But Nature (if she arranges anything) had arranged that from them, at all events, there should be a view.The whole system of the country lay spread before Rickie, and he gained an idea of it that he never got in his elaborate ride. He saw how all the water converges at Salisbury; how Salisbury lies in a shallow basin, just at the change of the soil… And behind him he saw the great wood beginning unobtrusively, as if the down too needed shaving; and into it the road to London slipped, covering the bushes with white dust. Chalk made the dust white, chalk made the water clear, chalk made the clean rolling outlines of the land, and favoured the grass and the distant coronals of trees. Here is the heart of our island: the Chilterns, the North Downs, the South Downs radiate hence.The fibres of England unite in Wiltshire, and did we condescend to worship her, here we should erect our national shrine.

Michael Ayrton

Skull Vision 1943

Oil on panel

64.8 x 83.2 cm

Photo: 2009 Amango Photography

Courtesy Jill Pomerance

The imprint of the supernatural upon nature would be of special importance to the loose knit and somewhat haphazard grouping of British artists and writers known as the Neo-Romantics (and as Dr David Mellor has described in his 1987 exhibition and survey volume, A Paradise Lost: The Neo-Romantic Imagination in Britain, 1935–55, Neo-Romanticism also extended to film and photography, and even Nigel Kneale’s television drama series Quatermass). A precursor to the Neo-Romantic sensibility can be found in the art and writings of Paul Nash.

Paul Nash

Monster Field 1938

Photograph

17 x 30 cm

Photo: Tate © Tate Archive

Nash maintains a poised course between the known world and the worlds of the subconscious, the mystical and the supernatural. His concerns are first and foremost those of how, as an artist, he approaches questions of artistic interpretation. But there is often – as for Forster – the presence of other-worldly strangeness and the mysterious. Writing for Country Life magazine in May 1937, Nash addresses the notion of inanimate natural forms possessing, in particular from the Surrealist point of view, their own sentience: “Here, therefore, is an immense background for research and speculation upon the mystery and mysticism of the ‘living inanimate’.” He adds later: “Now it will be obvious to the least observant that a number of forms in Nature have apparently accidental resemblances to human or animal features. Such oddities seem to me only interesting in a quaint way, and are popularly, and quite rightly, mostly attributed to the Devil. To attain personal distinction, an object must show in its lineaments a veritable personality of its own. It may be a stone which looks like a bloodhound, as the Avebury megalith; but it must not have only an amusingly canine look: it must be a thing which is an embodiment, and most surely possesses power.”

Cerith Wyn Evans

11.08.99, Munich (Total Eclipse) 2004

C-print

49.6 x 33.3 cm

Courtesy Jay Jopling/White Cube (London) © Cerith Wyn Evans

For Nash, artistic thinking combined a Wordsworthian communion with nature with Surrealist enquiry. From this emerges a particularly heady notion of Romanticism, in which, as the critic Myfanwy Evans wrote of the artist’s fascination with the ancient site of Avebury in Axis magazine during the same year, 1937, there was “no interest in the past as past, but in the accumulated intenseness of the past as present”. Nash’s work establishes a relationship with the landscape as history, and the identification of a slippage between two states, the past and the present, that becomes a central tenet of British art’s relationship with the presence of magic in the modern world.

John Piper

The Moon Over the Lake, Renishaw 1942–3

Ink and watercolour on paper

38.1 x 50.8 cm

Private collection

The Neo-Romantic sensibility had some occasional links to the world of contemporary operational magic; the artist Michael Ayrton, for example, became interested in the occult during the early 1940s and in the writings of Aleister Crowley, “The Great Beast”, who by this time was more of a Fitzrovian casualty and proto-Beat than a persuasive magician. The sickly, troubled temper of Ayrton’s paintings in the 1940s – Skull Vision 1943, for example – reflect in part his admiration for Henry Fuseli (1741–1825), who had been described by Reynolds (as Malcolm Yorke notes) as “Principal Hobgoblin Painter to the Devil”.

The mood of T.S. Eliot’s invocation of semi-derelict, genteel spiritualism (magic and occultism as lingering haute bourgeois or aristocratic interests left over from the formal European civilisation finished off by the two world wars) is also present in British art’s shadowy yet distinct relationship with sigils, Tarot and the unseen. Leslie Hurry’s dreamlike and semi-grotesque portraits have been likened by David Mellor to the shuttered decadence invoked by Huysmans’s novel of 1884, Against Nature. The English country house and its overgrown estates become, to use Mellor’s bravura definition, “obscured places where the curses of history and hysteria spoke together”. Such, too, would be communicated by John Piper’s eerie paintings of the Sitwell family seat at Renishaw Hall, or, in broader more apocalyptic terms, by Graham Sutherland’s darkling visions of a war-doomed landscape.

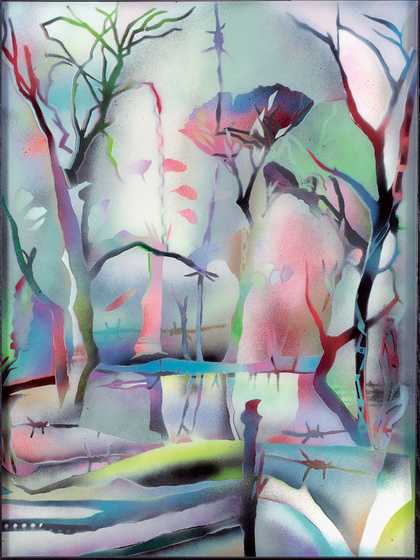

Simon Periton

Sordid Sentimental 2008

Spray paint on glass

82.5 x 62.5 cm

Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London © Simon Periton

The uptake of these themes by contemporary artists has maintained and extended the presence of the magical and the occult within British art. A linking figure between the Neo-Romantic sensibility and contemporary British artists is the artist, stage designer, filmmaker and writer Derek Jarman (1942–1994), whose interest in operational magic was a significant strand within his work, and who made visits to such sites of Neo-Romantic enquiry as Corfe Castle, Ely Cathedral and Avebury Ring itself. In his uneasy punk fantasy Jubilee (1977) and his film interpretation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1979), Jarman (whose assistants would include the artist Cerith Wyn Evans and the future film director John Maybury) employed an awareness of magic which he linked to both the technical processes of film-making and a semi-mystical sense of art. Fascinated by John Dee – court magician to Queen Elizabeth I – and by the Occult Philosophy of Cornelius Agrippa, in the “Spiders” section of his journal Dancing Ledge (1984), he writes of filming The Tempest: “My seventeenth-century copy of the Occult Philosophy was open on Prospero’s desk – its first English edition. On the floor the artist Simon Reade drew out the magic circles that were blueprints of the pinhole camera he constructed in his studio next to mine at Butler’s Wharf, thereby making a subtle connection.” The entry concludes: “As for the black magic which David Bowie thought I dabbled in like Kenneth Anger, I’ve never been interested in it. I find Crowley’s work dull and rather tedious. Alchemy, the approach of Marcel Duchamp, interests me much more.”

Clare Woods

Monster Field 2008

Enamel and oil on aluminium

274 x 732 cm

Courtesy Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London © Clare Woods

In addition to the aphoristic elegance of Cerith Wyn Evans’s engagement with magical and hallucinogenic thought processes in his work, one can also trace the lineage of Neo-Romanticism, and of an artistic vision combining the worldly and the unseen, in contemporary work as varied as Simon Periton’s recent paintings on glass and Clare Woods’s revisitations of Paul Nash’s Monster Field. Whether in gothic reaction to the encroachment of saturation technology, or as continued enquiry into the relationship between consciousness and place, the presence of magic as a subject, metaphor and even medium for artmaking remains in place. In his poem The Tower, W.H. Auden addressed the strange, portentous psychological crease in which such thinking resides: “Here great magicians, caught in their own spell, long for a natural climate as they sigh, ‘Beware of Magic’ to the passer-by.” As at Cadford Rings, once in, it is difficult to leave.