[T]hings things always and memories I say them as I hear them murmur them in the mud

Samuel Beckett, How It Is (1964)

Miroslaw Balka

How It Is 2009

Film still

© Tate Media/James Price

Miroslaw Balka

How It Is 2009

Film still

© Tate Media/James Price

Two Houses

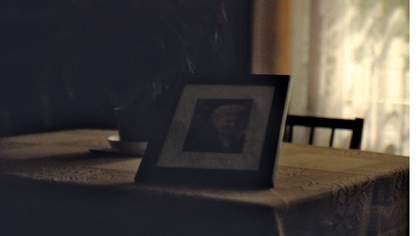

The first: built by the artist’s grandparents in the 1930s, provisionally out of wood. Only later, when the family could afford it, was the house clad in brick. It was here that Miroslaw Balka grew up, in a forested suburb of the town of Otwock, 24 kilometres south east of Warsaw. Recently, though he has lately also acquired a workspace in Warsaw, this house has functioned as his studio. The second: built by Balka’s parents in the modest, gated grounds of the first house in 1979. It was large by local standards, though it rose to only one storey above its spacious cellar. Outside, the walls were finished with fragments of marble and coloured glass – against this rough surface, the young Balka sometimes grazed himself. Inside, a local painter contrived a delicately veined simulacrum of golden-brown marble on the lower half of the walls. The furniture and décor in this house have hardly altered since it was built. His father still lives here. In the five years since Balka’s mother died, the museum of his childhood has simply faded slightly under a thin layer of dust.

Privacy

In neither house, recalls Balka, was there any privacy. It was, he says, a “primitive” existence; even after the move to the new house, the sounds and smells of proximate bodies were inescapable. The original house was shared with his parents, his older sister and maternal grandparents. For most of his childhood, there was the constant presence of illness: his grandfather had been partially paralysed in the 1940s. He remembers the persistent smell of urine. He recalls an incident when he was very young: playing with matches, he set fire to a plastic toy car, and might have burned the house to the ground had his grandfather not roused himself and begun a kind of slow-motion dance to put out the flames. When his grandfather died, he was laid out in a small room at the end of the house and for three days neighbours called to pay their respects.

Treasure

Certain objects persist from that life divided between the two houses: a hoard of “treasures”, of which he will be the last curator. An ornamental glass apple that fascinated him as a child. A squat clay “sculpture” of two indeterminate creatures with cave-like mouths, bought from a nearby shop where his grandmother told him he could have any object he wanted. The tiny plastic record player he acquired as a teenager. A solid and polished Sleza radio that still works after almost 30 years. Crucifixes, pictures of the Virgin, and the small square Solidarity badge that his mother placed high up, like an icon, on the kitchen wall. A thin metal stool with a blue latticed seat – it was among the first plastic items the family owned. A cellar room stacked with empty glass jars, dutifully saved by his father although there is nobody now to fill them each autumn with jams and preserves. The broom belonging to his grandmother, with which at the end of each working day he sweeps out the old house, adding another touch, a friction and some heat to the cool grey floors.

Materials

He comes from a lineage of collectors, and discovers poetry in what they did out of necessity: his grandmother’s hoarding of scraps of soap, a cellar stocked with potatoes, cucumber pickle and raspberry juice. To this inheritance, he has added his own store of things and substances that patiently wait their turn at the edges of his art: a pile of old shoes, a box filled with his own white t-shirts, dozens of frayed labels from the cheap wine he drank as a youth, floorboards reclaimed from a Warsaw gallery, a photocopied snapshot of his mother that he has pinned above a door, a shelf laden with delicate glass casts of vessels and receptacles from the old house, including a shallow metal bowl once used for the washing of bodies. Each year, he records the “undressing” of the Christmas tree, collects and labels its fallen needles. He feels a duty of care to these materials, a sense – which is not, he insists, a type of fetishism – that something inheres in them of the continuous past that will end with his own death. (It is unlikely, he notes, that his own children will inherit this responsibility towards such material remains.)

Gestures

It took him a year, he says, to become used to the studio that was once his home, to know how to move in it and to divine the proportions of the work that might be made there. It was a question of living with the limits of sculptures that would have to find their way out of the house through doors and windows, a matter (like much of his art) of bodily proportion. In this, he was perhaps guided by the evidence of certain gestures once made inside the old house. By a window that looks out now on trees laden with cherries and walnuts, a patch of ancient brown linoleum has been worn through to the wood beneath. He remembers that his grandmother sat here in the last years of her life, one softshoed foot moving rhythmically as she prayed, till she had gently dug this hole, this commemorative absence, into the fabric of the house.

Miroslaw Balka

How It Is 2009

Film still

© Tate Media/James Price

Miroslaw Balka

How It Is 2009

Film still

© Tate Media/James Price

Miroslaw Balka

How It Is 2009

Film still

© Tate Media/James Price

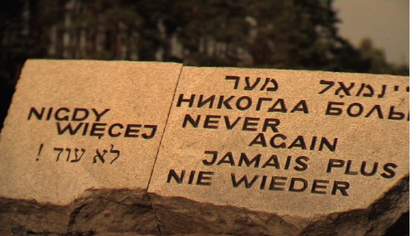

Museum

Balka’s grandfather was a memorial mason, his father a part-time engraver of headstones; a few slabs of dark grey stone still lie scattered in the garden. In the outbuildings by the perimeter of the property, among the rusted tools and the remains of the artist’s first bicycle, is the evidence of his own early career as a sculptor: here he can retrace his movement from the life-size to the monumental, from figuration to abstraction. Early on, he says, it was a matter of recycling: the rough wooden armatures of his sculptures are stacked in corners; a large plaster head of the Polish novelist Bruno Schulz sits atop the detritus; crude homemade packing cases in which Balka’s early works were transported are filled with friable decaying foam. The materials, he recalls, were almost as hard-won as the work itself.

Environs

Beyond the rusted iron gates, Otwock itself is a kind of museum, albeit a forgetful one; only obscurely or uneasily aware of the histories it contains. In places, the ornate wooden houses of its formerly Jewish population are still extant. Otwock was once a therapeutic resort; its woods were thought congenial to sufferers from tuberculosis, and they are still dotted with the ruins of elaborate sanatoriums. Their proprietors and patients were mostly Jewish; even in the early days of the Second World War, those with sufficient funds or influence might briefly escape the city for a sojourn here, before the fencing off, two streets away from the Balka family house, of the Otwock ghetto.

Years ago, in a nearby scrapyard, the artist came across a curious portion of rusted metal that he concluded could only have been part of the ghetto perimeter. Such, he says, is the nature of historical memory here: as a child, he knew nothing of the vanished population of the town, nor of the shameful appropriation of their empty houses by some of their fellow citizens. Even now, few among his father’s generation will speak of the events of those years; he consoles himself, at least, with the knowledge that the house that is also his studio was built by his grandfather before the war.

Transportation

On 19 September 1942, the Jews of Otwock were ordered to ready themselves for transportation. The many who refused, or went into hiding, were swiftly rounded up and summarily shot on Reymonta Street. (At the local mental asylum, 100 staff and patients were murdered on the same day; the psychiatrist in charge committed suicide.) The vast majority of the Jewish population – some 8,000 souls – were assembled on the platform at Otwock station before being taken to Treblinka. A single photograph, taken from a passing train, records their presence: a grey mass of blurred figures huddled on what is today the station car park. The railway line on which they travelled, long unused, still runs into undergrowth beside the modern platform and tracks. Since the early 1990s, an annual procession of perhaps 50 people has remembered the brief passing here of three-quarters of the town’s population, but for the most part it is as if they had never been.

Camp

Within a year of the murder of the Jews of Otwock, the camp at Treblinka had begun to disappear. Panicked at the thought of the discovery of their crimes, and in response to an uprising in August 1943, the Nazis covered the burial and burning pits, destroyed the gas chambers and other buildings, and installed a single guard and a sham farm to deflect attention from what Balka calls “the pain in the land”. When he walks this territory now, it seems to him that the proper memorial response is of the order of a certain flatness or horizontality. In the early 1960s a memorial made of massive concrete slabs that correspond to the sleepers of the railway line was installed; more fitting in its minimal (now decaying) relation to the land than the agglomeration of upright stones and explanatory plaques that marks the absent centre of the camp.

Animals

Among the structures that have vanished at Treblinka is the zoo erected by the camp commandant for the relaxation of SS officers and guards. A photograph of the wooden buildings, which housed foxes on the ground floor and doves above them, sits on a window sill at his childhood home. When he visits Treblinka, Balka says, it is often the animals that will stay in his memory after he leaves: birdsong from the trees, a flock swirling towards sunset, a lone fox caught in his car headlights, and during his most recent visit a noisy carpet of digger bees, burrowing their way into the sand around the stone monuments and leaving tiny mounds behind them.

Traces

Balka’s is an art, he says, of traces. At its most monumental, it conjures architectural horrors that recall (though obliquely) the absent structures in the woods at Treblinka: ominous concrete portals, wooden walkways that conceal their destinations. But it is an art, too, of the domestic, and of the proportions of the human body as it moves through space and leaves something, however frail and scarcely recoverable, in its wake. Its materials are as likely the steel and concrete of a larger and more vexed history as the wood, ash, soap and linoleum of the space in which he works and through which, like a child dispatched down to a darkened cellar for provisions, he is slowly retrieving the essential items for which he was not sent.