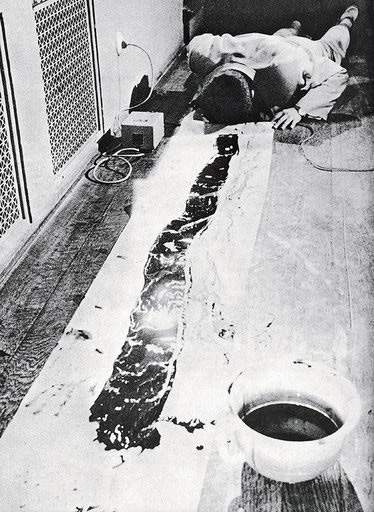

Nam June Paik performing Zen for Head at Fluxus Festspiele neuester Musik in Wiesbaden 1962

Photo: Harmut Rekort

Courtesy Kunsthalle Bremen © The Estate of Nam June Paik

In May 1999 the American magazine ARTnews included Nam June Paik in its list of the century’s 25 most influential artists, alongside Picasso, Duchamp and Rauschenberg. He had come a long way since 1962, when he presented One for Violin Solo at the Fluxus event Neo-Dada in der Musik at the Düsseldorfer Kammerspiele and shocked his audience in the darkened space by smashing his violin on a table. How did Paik go from enfant terrible to being the first professor of video art at Düsseldorf Academy (in 1982) and a universally respected star of the museum world? How did he manage to be both anti-artist and artist in one, to be a theoretician and practitioner of our networked world at the same time as he kept his distance as an ironic humanist? From the start his aim was not only to harness technological progress in communications media as an acceptable artistic tool, but also to use his own imagination to spur on that progress and, in so doing, to break down the seemingly rock-solid barriers between the different realms of art, including the ‘serious’ and the ‘popular’.

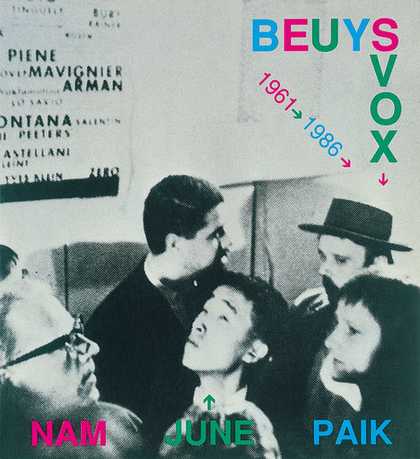

Cover of the catalogue for Nam June Paik’s Beuys Voice shown at documenta 8 1987

Courtesy Collection Peter Wenzel © The Estate of Nam June Paik

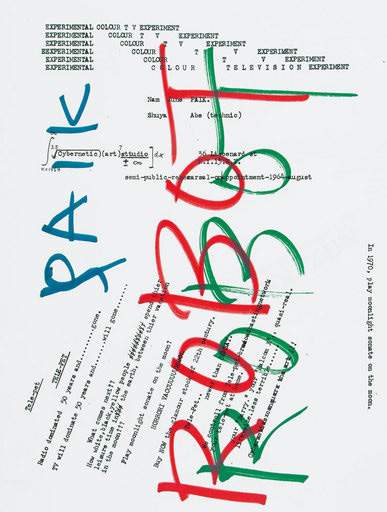

Invitation to John Cage’s Experimental Colour TV Experiment, overwritten by Nam June Paik 1993

Courtesy collection Peter Wenzel © The Estate of Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik (pronounced pike) studied in Japan, where he read Hegel in German and wrote a musicological thesis on Schoenberg. He often made the point that in 1957 Germany was particularly attractive to him because it was the centre of contemporary music. Still in Japan, he identified Wolfgang Fortner in Freiburg as his chosen teacher; however, it was at the Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik in Darmstadt that he was to encounter John Cage and the latest interdisciplinary advances in music. From there it was but a small step to Cologne and the hub of progressive musical activity that was the studio of the painter Mary Bauermeister and her then partner Karlheinz Stockhausen, the leading composer at the electronic studios of the WDR broadcasting station. The artists and intellectuals who gathered at the studio around 1960 were united in their determination to create a brave new Gesamtkunstwerk (total artwork) combining music, artistic action and literature.

Time and motion, sound and action, structure and shock all featured in the innovative output of these artists, who included such diverse figures as the architect Stefan Wewerka, the sculptor Christo, the Argentinean composer Mauricio Kagel, the writer Hans G. Helms, the ‘labyr artist’ Arthus C. Caspari, the musician Gottfried M. Koenig, the gallerist Haro Lauhaus, the restorer Wolfgang Hahn and the publisher Ernst Brücher. Their vision of a new Gesamtkunstwerk also embraced film and electronic developments in the field of acoustics – so it seemed only logical for Paik to make the transition to visual electronic art, where he set about introducing into the realms of visual art his experience of a new electronic audio world where sounds could be endlessly manipulated.

Paik would open up a whole range of possibilities in the new medium of video art: in March 1963, in Exposition of Music – Electronic Television (a wonderful, programmatic title for an exhibition), he first used television sets, responding to input from the viewer, to create electronic paintings (Participation TV). He was the first to demonstrate publicly and verifiably all sorts of different artistic uses for the medium of television, and this marked the beginning of a career during which he, more than any other visual artist, foresaw and actively influenced the technological, philosophical and social development of the new media – television, video, computers and lasers.

In 1965, in New York, he made his first video tapes. In 1969–70, with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, he constructed his first video synthesizer, for the television station WGBH in Boston. From 1974 onwards he started making large-scale multi-monitor installations, such as TV Garden 1974, initially seen in Philadelphia and re-created for Documenta 6 in 1977. For the opening of Documenta 6 he created the first live satellite broadcast with artistic works (by Joseph Beuys and Douglas Davis). By 1985 he was making figurative video sculptures (including Family of Robots); in 1987 he made his first compact multi-screen wall (Beuys Voice, for Documenta 8); and in the mid-1990s he started to combine lasers and video technology (on the grand scale for the Guggenheim Museum, New York, in February 2000).

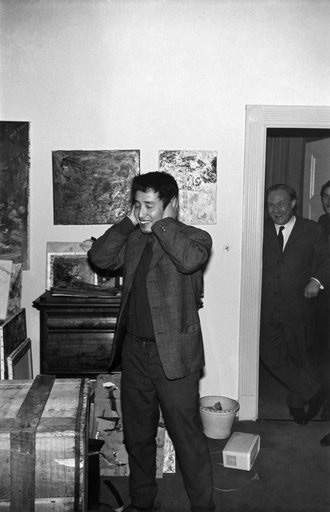

Video still from Nam June Paik’s contribution to Karl Stockhausen’s Originale performances, filmed by Wolfgang Ramsbott 1961

Courtesy Kunsthalle Bremen © The Estate of Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik during his Exposition of Music – Electronic Television 1963

Galerie Parnass, Wuppertal

© The Estate of Nam June Paik

Over the decades his work met with immediate acceptance from fellow artists and art historians alike. Although we know that the artists who come up with something new, who devise new methods and media, may not necessarily later turn out to have been decisive artistic personalities, Paik was to be both innovative and influential, because in his art he always also incorporated the polar opposite to technological progress – namely reduction, minimalisation and resistance. His output is notable for the fact that works with too much coexist with others that have too little.

The proud list of artistic technological premieres outlined above illuminates only one side of Paik’s art – the other was determined by his refusal to deploy new technologies. In 1963 he placed a TV set face-down on the floor, exposing the brand name, Rembrandt Automatic. In 1974 he created a piece where an antique statue of Buddha is seen watching itself on closed circuit television; in another a burning candle replaces the inner, electronic life of a monitor; and in One Candle the subject of the title fills an entire room by virtue of a technologically complex six-fold projection. These works raise issues that are a far cry from high-tech art: the poetry of artistic vision plays ironically with the rich possibilities of technology.

In one of Paik’s most revealing, complicated comments, in an interview with Russell Connor in 1975, he remarked that he loved ‘anti-technological technology’. And when he presents us with tiny real fish swimming in aquariums inside TV casings (Video Fish 1975), or a solitary goldfish in a converted TV set (Sonatine for Goldfish 1975, once part of the Sammlung Hahn, Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna), he is toying with the illusion created by the broadcasters that they are transmitting a wealth of endlessly changing programmes. Fifteen years later a German TV station, ORB, adopted this same image to fill the gaps in its schedule. And nowadays there is even a company selling DVDs of soothing little fishes in a TV aquarium.

A highpoint of Paik’s anti-technological technology has to be his 160cm Robot K-456 of 1964 (just a little shorter than the artist himself ). It was constructed with the help of the engineer Shuya Abe, a friend of Paik’s with whom he also later collaborated on the development of the video synthesizer. Although the remote-controlled robot perhaps looked a little helpless, somewhat fragile and cobbled together, it could fulfil various functions, such as walking, which is in fact the trickiest activity for a two-legged robot. It could also transmit music and excrete white beans. The robot made its first appearance in Wuppertal in 1965 at the 24-hour happening 24 Stunden.

Ten years later, in 1976, it could no longer stand upright and was exhibited in a crate, before being restored. In 1982, during his retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, Paik took Robot K-456 for a walk down Madison Avenue and staged the ‘first accident of the twenty-first century’ in the form of a collision with a car. In the age of high-tech robots designed to relieve human beings of certain tasks both at work and in the home, this rather human robot – like some of Jean Tinguely’s machines – conveys an ironic longing for a form of preindustrial, self-controlled technology that is, in fact, no longer viable.