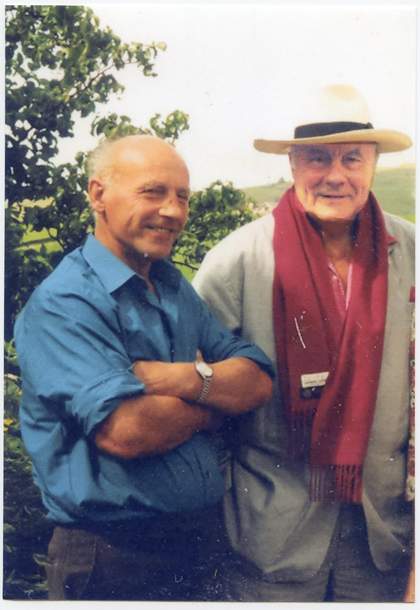

Patrick (right) and Giles Heron in the garden at Eagles Nest in Cornwall

It is the prerogative of younger brothers of public figures to prick the bubbles of reputation. So I have chosen to commemorate Pat’s supreme gifts of indecision and procrastination. You must excuse me calling him Pat, whom most of you probably think of as Patrick. To our family, both parents and siblings, he was always Pat or Paddy, or even Pandy. ‘Patrick’ was reserved for formal occasions and the next generation.

It was comparatively early in Pat’s career, early enough for it to be a great honour, that he was invited to speak in New York. After several weeks, when he still hadn’t answered, the American Embassy repeated the invitation, giving a deadline for reply. Pat was in agonies of indecision. He consulted Delia, but she knew better than to urge her own opinion. At last he decided, if that is the right word, that he would write a letter of acceptance, which he did. But he delayed posting it until it was too late. So he had to go down to Grosvenor Square to deliver it in person. It seems that the sight of all the Cadillacs and other out-size opulent cars surrounding the embassy triggered an incipient Yankee phobia. Instead of handing in his letter of acceptance, he found a phone box round the corner and rang to give his formal refusal.

In 1963 Pat had agreed to select the Welsh Arts Council’s annual exhibition of paintings and sculpture. He set off from Eagles Nest in Cornwall to drive all the way to Cardiff - with a sore throat. Just past Redruth he turned back, for half a mile, then thought better of it and resumed his journey. On Bodmin Moor he repeated his vacillation, again turning homeward for half a mile, before, as he said, pulling himself together. At Taunton, 150 miles from home, he went to buy some throat lozenges. He got such a look from the chemist he just turned round and drove all the way home.

It was inevitable that someone who found it so difficult to make a decision and stick to it should torture both himself and his beloved when he came to the brink of getting engaged. Falling in love didn’t involve any decision. Getting engaged did. Delia waited on Pat. Pat just waited. At one critical moment, when he was teetering on the brink, I remember our anxious mother ushering them out of our front door to go for a walk in the woods and saying to me: ‘When it’s your turn lad, for heaven’s sake be quick about it.’ Perhaps I owed it to Pat that years later Mary and I got engaged in less than a month after first meeting each other.

Anecdotes of Pat’s indecision and procrastination could go on all day, for each of you will have your own fond examples, and doubtless we should be greatly entertained. But this is no trivial matter. No merely trivial trait could have persisted throughout his life, exerting such influence over even the most vital aspects of it. One might say that there was method in his madness, only that would suggest a degree of conscious deliberation that was often not the case. Insofar as he was conscious of the processes at work -and I think very often he was - he was recognising what was happening rather than determining it.

But here I abandon knowledge and embark on conjecture. In some people indecision may result from limited awareness and understanding. Not so for Pat, with his extreme sensitivity and intellectual grasp of the full complexities behind every option. In his case one is more tempted to blame cussedness or lack of self-discipline. I would also add as contributory causes a kind of incorruptible honesty and a refusal to take the easy road out.

Why did he who said he preferred his tea or coffee hot, always let it go cold? What was he so stubbornly deferring by picking the finest crumbs off the recently swept kitchen floor while others waited for him outside with the car engine already running? Or why did he begin to readjust the pots and cushions in the sitting room, long after midnight? We can only guess. It seems clear that he was gaining time, time that perhaps he felt he needed because he wasn’t ready; unready, not for the immediate issue, but for something else.

Certainly it was a sort of protective device. It preserved him from habitual action which might preclude the spontaneous, the creative. Of course it didn’t save him nervous energy. On the contrary, it raised the temperature – his and other people’s. Maybe that was the point. Isn’t ferment more conducive to creativity than is compliance?

Procrastination can prolong room for manoeuvre, whereas decision curtails imagination. Perfectionism – a quality we all recognised in Pat – is the pursuit of the unattainable. Procrastination can prolong the illusion that the perfect is just around the corner.

All this is, as I said, mere conjecture. For you to test its validity let me indulge in one last anecdote. I had the extraordinary good fortune to be with Pat during most of what was to be the last week of his life. We had a wonderful time together, in holiday mood, going out somewhere different each day, always in the sun. The Tuesday morning, however, we earmarked for painting, so when the slow, protracted routine of bath, dressing and breakfast was at last accomplished, Pat prepared to paint. He washed a great array of brushes; he laid a clean sheet of paper on the table; and then he called Linda and me to go around the garden with him. This we did at a snail’s pace. We revelled in the dappled sunlight on the camellias. We inspected the greenhouse, which inevitably demanded a lot of watering. Of course it was lunchtime before we returned indoors, and the afternoon was already bespoke, for a professional engagement, mark you!

That garden stroll had prevented his painting in more than one sense. It seemed to me that what I was witnessing was not wilful or weak-minded avoidance of work, but slavish obedience to it, and that the garden experience was an inescapable part of the painting process. I suggested to Pat that this was the case. ‘Of course!’ he said.

When I returned for the funeral the following week there was the new gouache on the floor of the little front room where he painted latterly. It had captured the radiance of light and brilliance of colour we had been soaking up that morning when he hadn’t been ready to paint.

One final comment by way of epilogue. It has been observed that Pat’s death occurred with uncharacteristic speed. There was no indication of procrastination or indecision here. I cannot help thinking that this time he was ready.