Soldiers in gas masks, c1915

Courtesy Archive of Modern Conflict

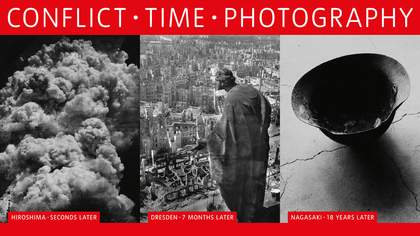

It is still a surprise to recall that the figure of the soldier is introduced by Charles Baudelaire as a personification of modernity, placing the soldier alongside the dandy and the prostitute in his essay The Painter of Modern Life. For Baudelaire, the fashioning of the modern warrior was a compound product of dress and bodily language which stemmed from what he called ‘the pageant of military life, of high life, of loose life… [the] showy apparel his profession clothes him in… a mixture of calm and boldness… soldiers are beings who have the indestructible appearance of returning from afar’. This cross-section selection of photographs – by turns forbidding and always ostentatious, all supplemented by metallised weaponry – are drawn from the collection of the Archive of Modern Conflict. Within them it is possible to glimpse a series of distinctive types and invented roles connected with the imaginary warrior across the planet over the course of the past century.

Constructions of the warrior have been foundational to global culture. As Omer Bartov has written: ‘War has always created a tension between its representation as an arena in which the individual warrior could display his heroic qualities and its reality of anonymous slaughter where the individual counted for very little. Yet notions of individual heroism and soldierly chivalry persisted in Europe well into the 20th century. The Great War seemed to totally shatter any illusions regarding individual worth and heroism.’

Students from Bedford Physical Training College, 1910

Courtesy Archive of Modern Conflict

Khevssurian warriors, c1908

Courtesy Archive of Modern Conflict

And yet in this 20th-century moment of the destruction of residual 19th-century martial romanticism, there is a brute recrudescence and schematic re-fashioning at the hands of soldier or airman writers such as Ernst Jünger, TE Lawrence, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and Guy Gibson. In this re-fashioning military-industrial technologies are embedded in the body, which acquires a fabulous glamour. We could think here of the impossibly baby-faced, transcendentalised German pilot portrayed in front of his Fokker D.VIII, the ‘Flying Razor’, which entered service in the last full month of the Great War. In another link to the revivification of the chivalric fantasy, applied to aerial warfare, the Fokker D.VIII was the aeroplane which won the last single combat dogfight against the Allies in the skies over the Western Front.

The fantasy of the Amazon – the female warrior – erupts within this predominantly male roll-call. With shields raised, two bobbed-hair women students at Bedford Physical Training College from the era of the suffragettes mime this, as if on a stage at the Arts Theatre, Cambridge, participating in an episode from Greek drama. A similar scenographic fiction is also at work in the Canadian carte de visite produced a couple of decades earlier. In this a genteel white Anglo settler woman has successfully maintained her hauteur while decked out as a native North American warrior with feathered headdress and bow and arrow. Her masquerade forms a point of comparison with the actual, non-masquerading Maasai tribesman from Kenya, who has been mapped as a living element of imperial ethnography.

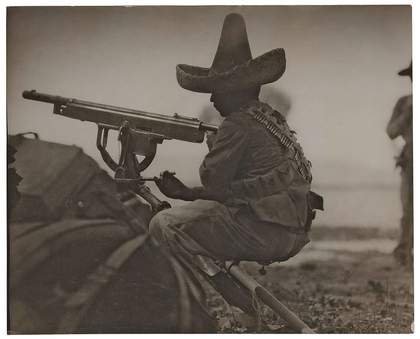

Rebel machine gunner, second Battle of Torreon, Mexican Revolution, April 1914

Courtesy Archive of Modern Conflict

Canadian carte de visite, 1880s

Courtesy Archive of Modern Conflict

As the Great War begins and industrialised killing comes to the marshes of Eastern Europe and the fields of Flanders, multiple temporalities are exposed and multiple versions of warriorhood displayed. Quite apart from the logic of an advanced war machine, survivals were to be found of past forms of martial styles which proliferated with anachronisms on all sides. For instance, the functionalist white robes and parkas of the winter camouflage of sharp-shooting elite Ottoman ski-troops evoke orthodox male Islamic dress. In 1908 five Khevsurian infantrymen from the Caucasus region, toting rifles and swords, posed in an apparition which, to Western European optic, resembled a variant of crusader-period armoured dress. The artist and poet David Jones agonised in the 1930s to find a way to superimpose the experience of front-line combat with that ‘medieval look’ of the British infantry uniform, with its steel helmet, overlaying it with the citational templates of archaic Celtic and Arthurian literary forms.

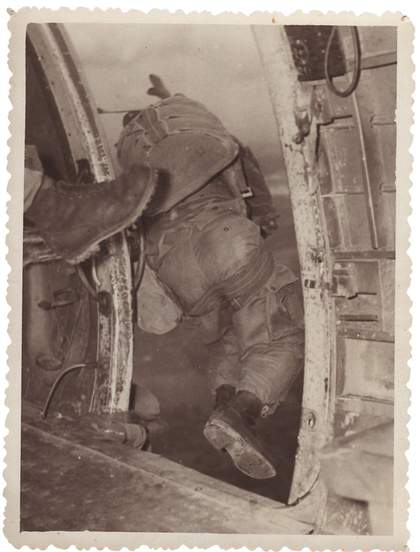

Paratrooper jumping, Second World War, US

Courtesy Archive of Modern Conflict

But some more hurried, instantaneous, documentations of warriorship rendered the unspeakable shocks of mobile, high-explosive warfare. Robert Capa’s reportage from Omaha beach, in the first wave of the Allied invasion of occupied Europe, was – in the view of Life magazine – marred by being ‘slightly out of focus’. Involuntary body movements had blurred the registration of the photographic image, while at the same time faithfully tracing the concussions of shellfire. Shock – a critical component of Baudelaire’s modernist method – reconfigured views of the world of war which were mediated by the photographer’s own recording body under siege. In what is at first sight a darkly comic photograph of a French parachutiste coloniale being booted out of a Dakota troop carrier in the mid-1950s, there is an acute metaphor of the military imposition of brute muscular force. The same narrative had previously caught up with Capa as his landing craft beached at Omaha on the morning of 6 June 1944. He had hesitated, under fire, and was for a moment distracted by his obligations to start taking action photos; then from behind him came a hefty encouraging kick from a US sergeant’s boot which pitched him into the foam and pebbles of Normandy.