Frank Auerbach in his London studio, 2001, photographed by Kevin Davies

© Kevin Davies, courtesy National Portrait Gallery

While posing, facing the back of the easel and looking off to one side, it is impossible to guess what is happening on the canvas. During my two hours in his studio Frank Auerbach is as active, in an extreme and strenuous way, as he was when I began sitting for him in May 1978, the month his retrospective opened at the Hayward Gallery. At the time I found him a highly intelligent, articulate artist, but already a reclusive one. He thrives, in his words, when he can make art in a self-forgetful state, wanting the resulting image to stand up for itself, not prone to looking back.

With a portrait his aim is not exactly to convey likeness, more an experience: how the person looks (including under the skin); what’s going on in their life (and his); the conditions of that evening. Like an apparition, something totally unforeseen, possibly lasting for just seconds, may spring from making a few brush strokes, establishing an area of truth which ‘might actually expand into a whole truth’. The goal is a set of connections between the masses, the space, the sensations and a picture with a tense surface character. After each session he scrapes off the paint and begins again. A single painting might take months, even years, before something appears that he hadn’t predicted and he hopes means the work is finished. (There is an analogy between Auerbach standing up, gesturing and drawing with a loaded brush, and a great actor’s days of endless rehearsals and then unexpectedly inhabiting the character, the performance perhaps unrepeatable.)

Frank Auerbach

Head of Catherine Lampert II 1985

Charcoal and chalk on paper, 756mm x 721mm

© Frank Auerbach, courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London

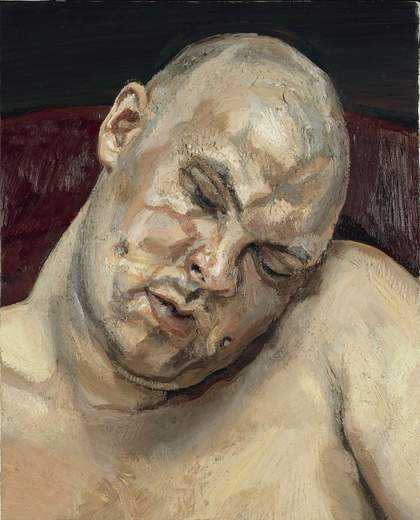

Frank Auerbach

Head of Catherine Lampert 1988

Oil on canvas, 610mm x 711mm

© Frank Auerbach, courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London

Frank Auerbach

Head of Catherine Lampert 2003–4

Oil on canvas, 514mm x 559mm

© Frank Auerbach, courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London

To prepare for the conversation printed in the catalogue for the Hayward exhibition, I went to see paintings in private and public collections and spoke to early collectors such as Frank’s school friend the filmmaker Michael Roemer and David Wilkie, who commissioned the pictures after Titian in the 1960s that are now owned by Tate. Reading through various archives, I could tell that Auerbach responded with some impatience to those tasked with writing entries for new acquisitions. In reply to Penelope Marcus’s and Anne Seymour’s questions regarding Primrose Hill 1967–8, and in a letter to Sir Norman Reid, then Tate director, the artist protested at this painting being described as a visual record of the motif over time. Despite the existence of 50-odd sketches, made each morning on site for over a year, he explained that the work is a single indivisible image: ‘There is no one-to-one relation of mark to object (such as lamp post, branch, puddle, etc)’, the goal is ‘to put down the mind’s grasp of their relationship’, the experience more haptic than retinal. He reminded them:

Art is the performance of remarkable feats and requires exceptional efforts… Painting is a dumb activity, it has its own language, and it is, of course, essential to watch what the conjurer does and not listen to his patter.

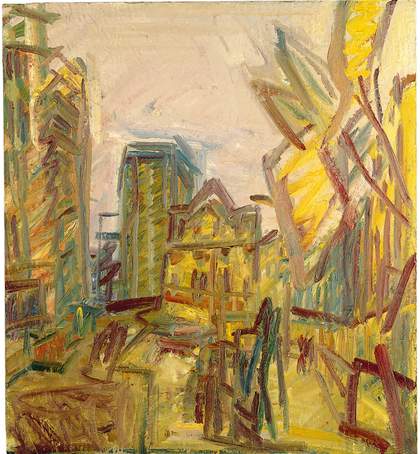

Frank Auerbach

Primrose Hill, Spring Sunshine 1961–2/64

Oil on board, 1125mm x 1400mm

© Frank Auerbach, courtesy Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

Frank Auerbach

Winter Evening, Primrose Hill Study 1974–5

Oil on board, 1067mm x 1372mm

© Frank Auerbach, courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London

TJ Clark, author of the essay in the 2015 Tate catalogue, looked closely at the Primrose Hill landscapes, and in front of the dark Winter Evening, Primrose Hill Study 1975 suggested to the reader that here nature ‘may leap into being, with emptiness and coldness always haunting it, but what matters most about the leap is that it – the thing itself, the scrawled contingency – is beautiful’. And, above all, ‘the feeling of seeing is his subject’. Auerbach once used as an analogy a phrase by Robert Frost about his own verse:

"I want the poem to be like ice on a stove – riding on its own melting.” Well, a great painting is like ice on a stove. It is a shape riding on its own melting into matter and space; it never stops moving backwards and forwards.

Frank Auerbach

Hampstead Road, High Summer 2010

Private collection © Frank Auerbach, courtesy Marlborough Fine Art Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.

Frank Auerbach

Mornington Crescent Looking South 1996

Oil on canvas, 635mm x 508mm

© Frank Auerbach, courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London;

What continually amazes me is how mobile his paintings remain, in the sense that they change with the angle and the light. You are drawn deeper and deeper into the soul of the subject, the inflections and the drawing so expressive. The urban landscapes mirror the times – labourers with wheelbarrows in the 1950s, and in the past decade a jogger with a backpack. If Auerbach hadn’t stayed in the same studio in Mornington Crescent, Camden Town, since 1954 and wasn’t working every day, for many years from the same five people and nearby locations, and if he hadn’t uniformly resisted professional appointments or invitations to speak, he might have become a pundit, or indeed an artist with an international life. But equally he might never have arrived at the large 2014 interior with a phantom self-portrait in the corner.

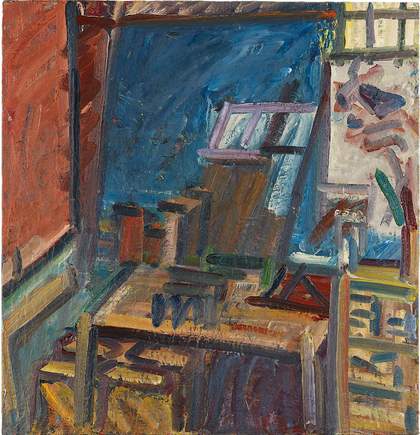

Frank Auerbach

In the Studio IV 2013–4

Oil on canvas, 1225mm x 1175mm

© Frank Auerbach, courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London

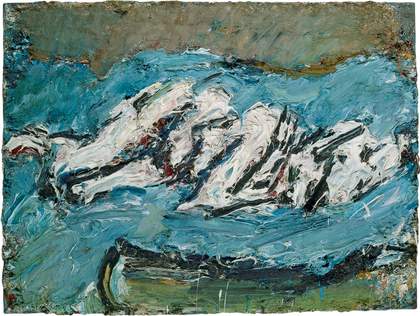

A few years ago, looking at a reproduction of a painting of Stella (the model referred to consistently by Auerbach as E.O.W.) on her blue eiderdown from 1965, Frank remembered:

I would have lots of paint around me, with the painting resting on a very, very paint-y chair. I never found these conditions irksome, to be on my knees and not able to get too far away from the painting, because, finally, all that thing of unity is in one’s head as much as it is found by looking. Like time travel, these things unlock memories for me, sometimes more, sometimes less. It certainly takes me back to a time which, after all, is 50 years ago. It does that thing that painting is supposed to do, that is to drag the past into the present and reanimate it.

What a remarkable and resilient thing painting in oils can be, in the most daring and persistent of hands.

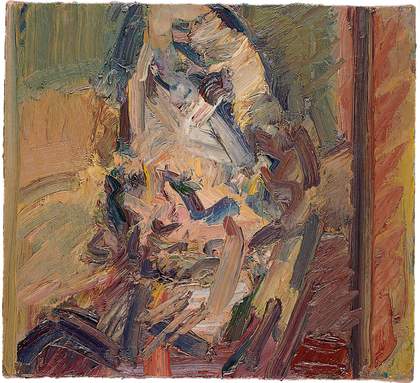

Frank Auerbach

E.O.W. on Her Blue Eiderdown 1965

Oil on board, 59.7 × 81.3cm

© Frank Auerbach, courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London