This is not a dream, or a nightmare: you’re in a glider about 1,500 feet above the ground, searching the sky for an elusive current. If you find it, you will be able to continue flying; if not, you will have to land in about six minutes’ time. Nearby you see a promising cloud and head for the air directly beneath it, checking your position and hoping for lift. Time slows. Then suddenly and quite violently the right wing tip is kicked up. That is the fringe of a thermal, where rising warm air scuffles with falling cool air. Peter Lanyon compared that moment with meeting a barking dog. Immediately you turn hard right, banking steeply, using the wing tip to feel out the contour of the thermal. You are now in a wheeling turn being buffeted by the rough air at the outer part of the thermal, but you keep pushing the wing and then the whole aircraft further and further into the thermal, and as you do the air becomes smoother. Here, at its core, it lifts your half-ton glider in an upward spiral at more than 800 feet a minute. And that is what you’ve been looking for.

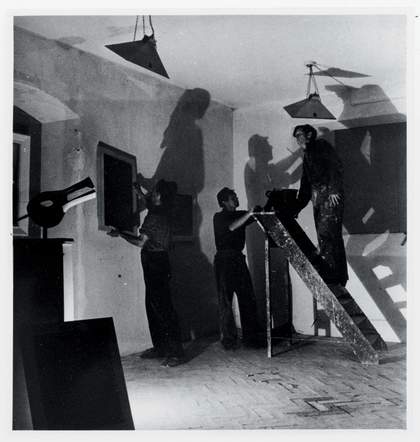

View of Porthtowan beach from a glider, September 1960, photographed by Peter Lanyon

© Estate of Peter Lanyon

Put simply, a thermal is a huge bubble of rising warm air generated by temperature differences on the earth’s surface – a colossal and largely invisible force that carries an estimated 1.4 trillion tons of moisture into the sky every day, where much of it condenses into cumulus clouds. On the ground, if one can see it at all, it appears as no more than a thin and fragile haze. Higher up, as the differences in temperature within the air increase, the warm air, which is less dense than the cool, gathers itself and rises with great force. Glider pilots are very familiar with this phenomenon, because to fly a glider is to become intimate with the interior life of the lower troposphere. There the sky is like the sea: endless, constantly active, prone to sudden and extreme changes. It can be nagging, boisterous, violent and suddenly calm. And the pilot seeks these moods and exploits them. For Lanyon, who started gliding in 1959, it was a revelation that led to a remarkable group of works, of which Thermal, produced in the spring of 1960, is one.

Peter Lanyon

Thermal (1960)

Tate

In the painting the thermal is forming in the lower left, where the thin grey-blue paint, vertically stroked, passes through the white chicane and begins to rise. Immediately above, where it meets a white mass, grey-blue condenses into a swirl of dark blue, and then, as it continues to rise, develops into the large pocket of grey in the upper left. Lanyon described this as ‘terrific turbulence – action going up on the left-hand side’.

In normal flight the air beneath the wings supports the glider, and in a thermal that sensation of being supported becomes a definite sense of being lifted. To fly into a thermal’s opposite and attendant force, sinking air, is different; then it feels as if the air, suddenly enfeebled, has dropped the glider. In fact, what is happening is that a block of cold, heavy air is taking you down with it as it falls through the sky. That sensation of a sudden loss of power finds an equivalent in the slower, more diffuse motion on the right of the painting, where marks elide, shapes loosen and colours darken into a heavier register.

Lift and sink; naissance, maturity and demise; vigour and frailty; battle, support and abandonment; loss. Before he learned to fly, Lanyon wrote of the sea that it was ‘closest to our human instability, waywardness, fickleness, mood and temper – it is perhaps an echoe [sic]’. Through gliding he entered the inside of the sky and discovered another mutable realm, less charted by artists than the sea, but as rich with metaphorical meaning. When John Constable commented that the sky was the ‘chief organ of sentiment’ in landscape painting, he wrote not just as a painter discussing a matter of composition, but also as a man who saw the work of God within the natural world. Lanyon, living in a less religious age, heard therein an echo of man’s complex self.