Photograph showing a distorted image of Nigel Henderson, date unknown

© Nigel Henderson Estate / Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

I have been asked to write something about Nigel Henderson, my great uncle – the seminal British post-war artist, photographer, collagist, printmaker and teacher. However, he has always been a rather mythological figure for me, since I never really knew him in my own life, nor in his, as he died in 1985 – my second year on this earth. Yet I have known him in his death and through his death-making, which is to say his artwork.

Nigel continues to be animated within the family through stories and anecdotes (all larger than life and greater now seen in retrospect), and through the remains he left behind in negative, in glue, in print and paint, in pencil inscriptions in notebooks, in shadowy impressions left on light-sensitive paper. And I remember, on visiting the old family home in Thorpe-le-Soken, Essex, a feeling of a ghostly ectoplasm materialising itself among four enormous boards, intricately collaged from top to bottom from top to bottom with images and words cut from magazines and newspapers.

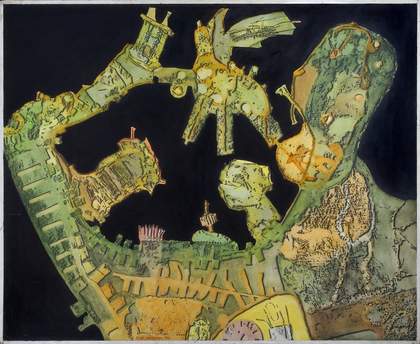

Nigel Henderson, Plant Delta No. 5 1961, mixed media on board, 125 x 155 cm

© Nigel Henderson Estate, courtesy MACBA Collection, MACBA Consortium

A layer of dust and the slow decay of the materials managed to incorporate themselves into the aesthetic organisation of the collage, producing new unseen forms that oscillated between nature and art: the mould in the corner of the damp board exuding new life as the image underneath deteriorated. Perhaps Nigel was haunting that moment, and reminding me that ‘… in the midst of death, we are in life’. This phrase (found in a prose poem in the Henderson collection in the Tate archive) is perhaps one of the most important keys to understanding his work.

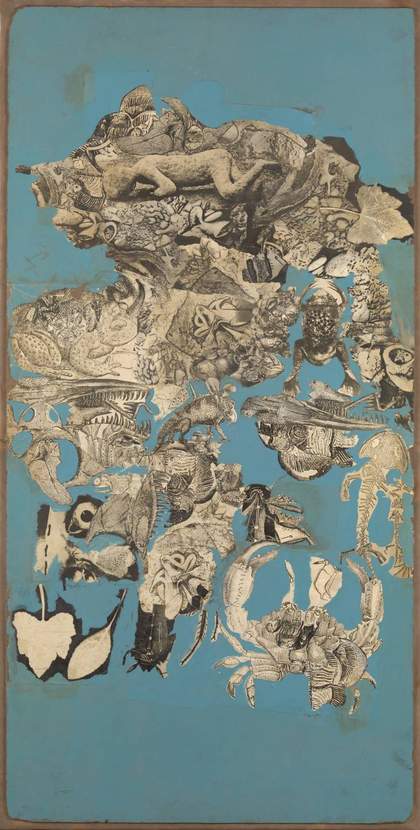

Nigel Henderson, Collage for ‘Patio and Pavilion’ (cycle of life and death in a pond) 1956, printed paper and paint on wood, 243.8 x 122.1 cm

© Nigel Henderson Estate, courtesy Tate Photography

There is much to be said about Nigel’s life, too much perhaps – and I feel that so much has already been written on his far-reaching and famous connections. All of this can be read in almost any piece of writing on Nigel, yet I believe it is more important to speak of his artwork and the way he approached his life through the making and use of images. And how his life as an artist was something he almost stumbled upon, as a way to keep himself moving, to keep his heart beating, as he once noted in a personal letter: ‘I just walked and walked and kept staring at everything. And it occurred to me after a while that I might try carrying a camera with me, but it wasn’t that I decided to be a photographer.’

Nigel moved to 46 Chisenhale Road in Bethnal Green in the East End of London after the Second World War with his wife, the anthropologist Judith Henderson (née Stephen), so that she could conduct research on the British working class: a social observation project called Discover Your Neighbour. He had been dismissed early from his services as a pilot in the RAF due to a nervous breakdown, and had been given an ex-serviceman grant to study art at the Slade. He spent his days wandering around Bethnal Green and Bow, neighbourhoods that had been very badly bombed during the war, yet he found life thriving among the fragmented and shelled city still resonating so strongly with recent death.

Nigel Henderson

Chisenhale Road (1951)

Tate

On these dérives Nigel photographed the activities that played out in what he saw as ‘the intimate box-like scale of the East London streets. Like little theatres’. This eventuated in his famous images of the surreal aesthetics of everyday life in post-war Britain: children playing hopscotch in the street, a window cleaner’s funeral, the skeleton of a bombed- out house, a woman’s face framed between mannequin heads on a market stall.

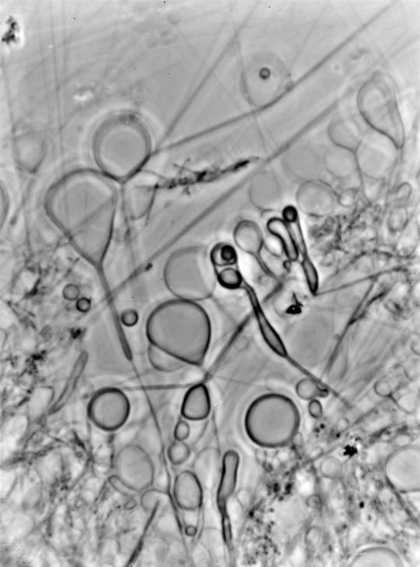

The photographs that he took were of images that pertained to the world, with their own natural/artificial systems of pictorial organisation, and as such they should be considered as objets trouvés, images created ‘as-found’. Perusing bombsites, he would pick up bits of rubbish, excavating waste such as pieces of wire, old rat-traps or broken milk bottles. These would end up in his first experiments of placing objects on to light- sensitive paper and casting their imprints with the light from a photographic enlarger. Ghostly shadows revealed abstract patterns of the world, reminiscent of the life forms Nigel had seen through the microscope when studying biology as a young student.

Photograph of a photogram of a milk bottle by Nigel Henderson, 1949–51

© Nigel Henderson Estate / Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Photograph of streptobacillus moniliformis through a microscope, found among the papers of Nigel Henderson in the Tate archive

© Nigel Henderson Estate / Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

All of this bears a relationship to a particular form of collage and the idea of finding images among materials that have been discarded by society. His work consisted of collecting what had been considered as waste, what had been left for dead, and allowing it to come together in a new space within which it would compose new forms of life, together in symbiosis, in sympoiesis. Metaphorically speaking, this practice is akin to making compost. Nigel was not merely a collagist, but a compostist. Compost can produce humus, a rich organic matter that helps cultures to grow. Humus – a Latin word that means soil, and that carries with it connotations of the burial of the dead, of the underworld, the world of the spirits, but also of being grounded, ‘down to earth’, humble (thanks to my dear friend F.C. for teaching me this). It is perhaps in this sense that Nigel was always destined only ever to exist in his death, and from the beginning he was working towards becoming a posthumous artist – an artist brought alive after burial.