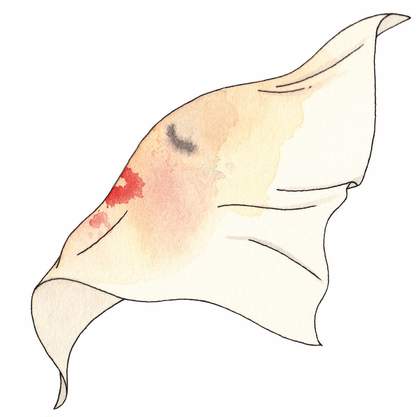

Illustration by Laura Callaghan

In the 1997 film Face/Off, John Travolta’s cop face floats in a vat of water. It’s been lasered clean away from his skull. He swaps faces with a crazed Nicolas Cage through a clear plastic face-transplantation device. It looks so gory and easy. When you take someone you know at face value, even if they started acting like a completely different person, the last thing you’d expect is that another has stolen their face and is impersonating them for plot purposes. If you were superstitious, perhaps you would assume they were possessed. Faces are taken as a matter of fact, of social currency. To ‘lose face’ means to suffer from public disgrace. Faces are judged in airport security, on the streets, on TV, in mirrors every morning.

In 2018 you can go on your phone and swap your face with whomever you like. Two faces float side by side in yellow, egg-shaped outlines. This swapping is painless and uncanny. The intended effect is light-hearted, comic. You can modify your face if you like. Add antlers or make your eyes go Disney-big. Dating apps mean you can flip through the faces of men and women in your city. Once I met a man at a bar whose face I thought I liked. When he told me he had lived in Japan and could speak Japanese, my face dropped. I am not Japanese, but my Asian face is a fetish, impersonal and skin-deep.

A news report comes out that skin creams containing paraffin have been linked to accidental fire fatalities. A spark from a cigarette reacting with a flammable emollient cream. Remember Venetian Ceruse, or the Spirits of Saturn, the milky, white face dye with white lead that caused lead poisoning in the 16th century? Why are there such nice names for bad things?

We hit puberty and our baby faces violently bloom. Nobody caresses puberty, except a select few. One suit of suddenly temperamental skin covers the top of your head, and all the way down to your toes. Hormones in a hurry. A clumsy collision. Pimples erupt. Eczema flares. Since age 13 I’ve been afflicted with stubborn blackheads that cluster on my nose like the grotesque achenes of a strawberry. When someone peers at my face too closely, I recoil in shame. A better name for those pore strips that you apply to a wet nose bridge, allow to dry and rip off ruthlessly should be shame strips. Shame torn from shame only inflames the thing.

For most of my twenties I was fecklessly and stubbornly in love with an ex; a preoccupation that spoke more of my mawkish tendency to romanticise and retread than any exceptional qualities of the former relationship. I kept seeing his face in crowds. Like a heightened version of ‘Where’s Wally?’, spotting and finding his face was the emotional crescendo, the self-absorbed but subject-fixated crux of an inchoate, yet essential gesturing. I affixed all longing and the cogitations of high emotion to the morphologies of his face, which became an avatar for: I want more. I’m bored. I feel things less vividly these days, with or without somebody. Would it be different if things had been different? What if? On a couple of occasions I identified him correctly and we exchanged a few strained pleasantries. Most other times it was just a shadow-twin, some stranger’s features shaped into fleeting recognisability. The shock of the known coalescing into the matter-of-factly unknown (or vice versa) never fails to be startling, hopeful and ultimately underwhelming.

‘You look tired’, other people sometimes comment. I have always taken this to imply that I look sad as well. I wear my feelings on my face. I have often been told that I cannot control my smiles or grimaces. I googled ‘how to stop my face looking so sad and tired all the time’ and a warren of links led me to an exquisitely beautiful woman teaching facial yoga. She makes all kinds of elastic, nightmarish expressions in her videos. If she popped up on your browser suddenly, mouth curled into an exaggerated oval, eyes squinted in clock-defying concentration, you’d scream. She looks great, but I’m dubious about whether this is due to her crazy exercises, or just genetics.

Have you ever met a sweet person with a sour face? Or a sour person with a sweet face? At what point do we sweeten or sour? Does this only happen in childhood, or can the taste of a face take turns and traumas to soften, to curdle, to thicken or thin? ‘Take the years off’ products say, and what this means is a promise to smudge the contortions of life and pain away. Who doesn’t want to look happy, trustworthy, clear of conscience, open to everything?

A beauty mask is a serviette soaked in serum, cut to accommodate the holes in your head. A sheet mask is an occlusive shield against the world. It’s meant to lock in moisture if you leave it on for the requisite 20 minutes. Overstay its welcome and it starts sapping the life out of your cheeks. This is inaccurately paraphrased advice, gleaned from translated Korean beauty packaging. Late at night, in a sheet mask, I resemble Michael Myers from Halloween, disarmed. Even homicidal maniacs need their downtime. You can’t be hell-bent on vengeance 24/7. Masks are spooky. Masks are silly, too. There’s something inherently vulnerable about how wet and trapped one’s eyes look, peering out darkly from behind a thin white mien.

Sharlene Teo is a writer, born in Singapore and living in the UK. Her debut novel Ponti is published by Picador.

Laura Callaghan is an Irish illustrator living and working in London.