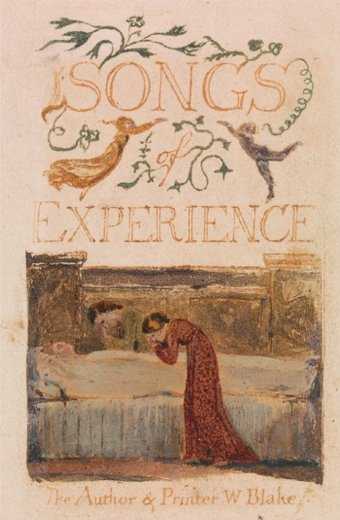

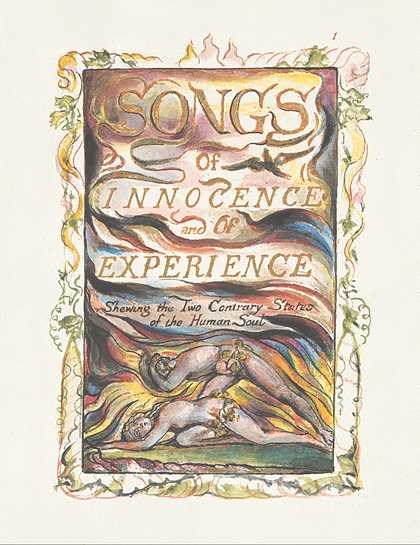

William Blake, title page of Songs of Innocence and of Experience Shewing the Two Contrary Sates of the Human Soul 1794, 54 relief etchings, hand-coloured with watercolour, with some gold, bound in calfskin, 11 × 7 cm (page size)

Photo © Tate

Both my parents loved poetry; my Jamaican father had tapes of Louise Bennett, more commonly known as Miss Lou, and would play them to me. My father was always adamant, too, that Bob Marley was a poet and a prophet. Meanwhile, my English mother loved William Blake, whom she would also speak of, with equal verve, as a poet and prophet.

One of my earliest birthday gifts from her was a copy of Songs of Innocence and of Experience alongside a cassette tape of Bob Marley and the Wailers. It would be years before I realised the kind of grounding my parents were giving me with the presence of these poets and prophets. But to think specifically about Blake and how his work spoke to a British-Jamaican boy growing up in 1990s Hackney, I have to go back to an incident that happened after a day at my primary school.

I was 10 when my mum overheard me singing a song: ‘Christopher Columbus was a great hero!’ Mum was in her bedroom making jewellery. Her pliers dropped: ‘WHO TAUGHT YOU THAT SONG?’ ‘School!’

My Dad’s response was to put a picture of Marcus Garvey on the wall and tell me about the pride Garvey has given to black people. He then played me a song by the Wailers called, ‘You Can’t Blame The Youth’, written by Peter Tosh but sung by a young Bob Marley: ‘You teach the youth about Christopher Columbus / And you said he was a very great man’, which is sung with seething irony, while my mum showed me a William Blake poem called ‘The Little Black Boy’ (1789) and used this poem to model an English voice, a poet and conscientious abolitionist writing at the peak of the transatlantic slave trade.

Blake, like Marley, would certainly not have agreed that ‘Christopher Columbus was a great hero’ – that in fact the cruelty of the slave trade had distanced Europeans from divinity. It has to be stressed that Blake wrote this poem before the abolitionist movement was popular in England. Both Thomas Clarkson and William Wilberforce (credited for popularising English anti-slavery sentiment) were young men when Blake was writing.

The black presence in the education I got at home from my Rastafarian father included Samuel Sharp and Nanny of the Maroons in Jamaica, as well as Toussaint Louverture in Haiti; all were important for washing out the taste of the ‘white saviour’ line that I was fed in my English state school. But Blake, too, didn’t reach for the white saviour narrative.

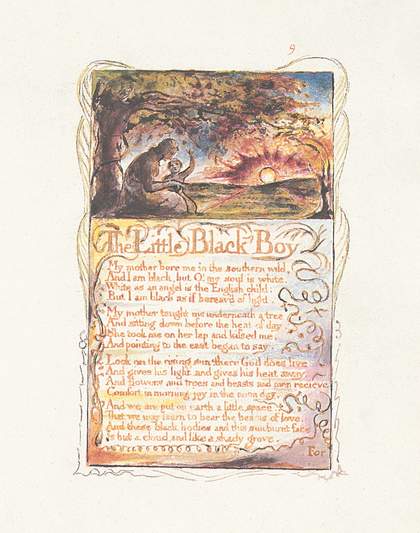

William Blake, Songs of Innocence and of Experience 1794 open at ‘The Little Black Boy’

Photo © Tate

Blake’s poem, ‘The Little Black Boy’, revises white supremacy. The most charged colours in the poem aren’t the polarising white and black but ‘gold’ and ‘silver’, which, in Blake’s spiritual and anarchistic realm, transcend their materialistic value and instead represent wisdom and moral soundness (‘golden tent’ and the ‘silver hair’).

‘The Little Black Boy’ himself also speaks without being reduced to victimhood. In fact, he bears a gift, his own wisdom, which he offers to a ‘little English boy’. ‘I’ll shade him from the heat till he can bear / To lean in joy’. The heat, the sun and the boy’s blackness are all framed as gifts without becoming one-dimensional symbols of persecution.

In fact, Blake wrote another poem, ‘The Chimney Sweeper’, the same year, which addressed the plight of English children who were sold and forced to work in chimneys and mines, where many of them suffocated and died. That year a bill was pushed through Parliament to make it illegal for children under eight years old to be forced into child labour (which remained legal for another 60 years).

This is what my mother was trying to show me in Blake’s poetry: that it was important to create more nuance and imagination when thinking about our national history, that my identity did not have to be defined solely by persecution and British colonisation. Marley sings this too, that ‘none but ourselves can free our minds’ – and our minds can’t be free without knowing how complicated the stories of imperialism and resistance are. We need visions of our own, our ‘Zion’s’ or ‘Jerusalem’s’, our ‘Demons’, our ‘Duppies’.

That lesson was in me somewhere when I next heard my father playing Bob Marley’s ‘Redemption Song’ on his sound system, while Blake’s book of poems vibrated on the shelf. Both Blake and Marley, poets and prophets, meeting somewhere inside me, their songs of innocence and experience, their emancipation from ‘mental slavery’.

William Blake, Tate Britain, 11 September – 2 February 2020, curated by Martin Myrone, Senior Curator, Pre-1800 British Art and Amy Concannon, Curator, British Art 1790–1850, Tate Britain. Supported by Tate Patrons and Tate Members.

Raymond Antrobus is a London-born poet, author of To Sweeten Bitter and The Perseverance. This year he won the Ted Hughes Prize for poetry as well as being the first poet to be awarded the Rathbones Folio Prize.