Andy Warhol posing as Invisible Sculpture, New York City, 1985, photographed by Paige Powell

© Paige Powell

Who needs Andy Warhol in 2020? There’s an obvious answer to this deceptively simple question: Museums! Auction houses! The High Street! This trio, embedded in cultural clout and commerce, has almost always needed Andy, or at least been aware that they could consciously monetise him ever since his untimely death in 1987. Warholiana makes serious bank – whether it’s a rare masterwork at Christie’s, a Campbell’s Soup Can tchotchke or Marilyn Monroe T-shirt. As the decades have passed, Warhol’s ability to generate capital, draw an eccentric crowd, and generate reams of publicity (which he famously measured in ‘inches’) has only increased exponentially.

Thanks to his posthumous success, even the general public knows that Warhol transcends the traditional confines of the fine arts: his work, as countless exhibitions and books have shown, is a polymorphous, performative terrain that collapses painting, sculpting, filming, recording, publishing, shopping, hoarding, gadflying, model-for-hiring, diarizing and just plain living. And, just as the embrace of the market and persona is part and parcel of Warhol’s DNA, it is perhaps unsurprising that this giant of 20th-century art has snowballed into a 21st-century populist-monetary juggernaut.

But this side of Warhol is actually the least vital part of his story in an era now dominated by Kardashianism – a paradigm of empiric proportions that conflates business / art / persona and media, and which was prefigured by Andy himself in his late ‘business art’ period. The expedient answer to who needs Warhol, revolving around money and celebrity, does not address the urgency of rethinking him today.

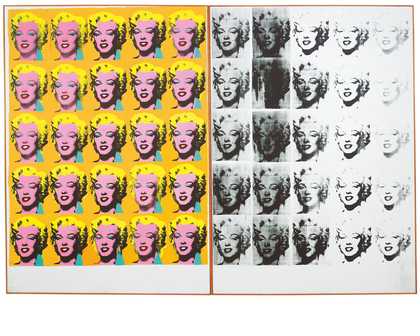

Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych 1962, acrylic paint on canvas, 205.4 x 289.6 cm

© 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London

We must rephrase our opening question: who really needs Andy Warhol now, at the start of the second decade of the 21st century, in our tumultuous age of Trump and Brexit? Putting blockbuster ticket sales, exhibition queues and auction prices aside, who could actually use Andy Warhol? Isn’t there a more poignant, personal Andy? Who might gain solace or fortitude from an artist and man who was able to reconcile himself to his humble roots as a first-generation American from Eastern Europe, a man who immortalised, and participated in the glamour of the rich and famous – and yet still maintained a deep devotion to his Catholic faith?

Andy Warhol with his mother, Julia Warhola, in 1958, photographed by Duane Michals

© Duane Michals, courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York City

Equal-opportunity Andy

Andy Warhol may have desired men, but he needed women. There are obvious types of Warholian women: the celebrity subjects, the underground film muses, the arm-candy socialites, and the aspirational paying clients. But there are also the unsung Warhol Women: a legion of equally essential protagonists who may have been pushed into the footnotes yet played a crucial role in every aspect of his practice.

From the heyday of the Silver Factory to the buzzing cross-pollination of Interview magazine (founded by Andy and journalist John Wilcock) and Andy Warhol Enterprises, there was of course a gendered division of labour in the Warholian sphere. ‘Andy surrounded himself with boys in the 1950s’ writes Wayne Koestenbaum in the most eloquent and insightful Warhol biography penned to date. ‘Beauties congregate with beauties … Bordered by beautiful men (and, later by beautiful women) he began to resemble them.’

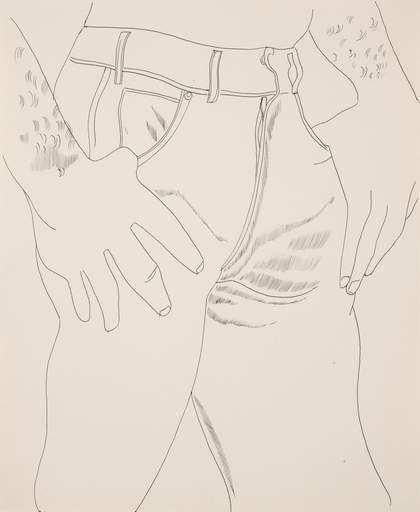

Andy Warhol, Male Torso 1956, ink on paper, 42.5 x 34.5 cm

© 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London

His band of nubile guys primarily fulfilled ‘management’ duties in the office, drumming up business as well as assisting with production in the studio. Warholian insiders and aficionados were on a first-name basis. But for every handsome Gerard, Billy, Paul, Fred, Vincent, Ronnie, Chris, and Bob, there was a gorgeous Edie, Nico, Brigid, Candy, Ultra Violet, Viva and Baby Jane. These mythologised co-conspirators and Factory family members were omnipresent: collaborating, performing, supporting, goading and documenting in a symbiotic relationship with Warhol’s borderless art / life maelstrom. Warhol wasn’t a gender ideologue. Man / woman, desire / necessity: these binaries spun out in his lifetime not as warring opposites, but as fluid interdependencies.

Edie Sedgwick (left) dancing with Gerard Malanga (centre) and David Whitney (right) at a party in full swing at Andy Warhol's Factory, New York City, c1965, photographed by Bob Adelman

© Bob Adelman Estate

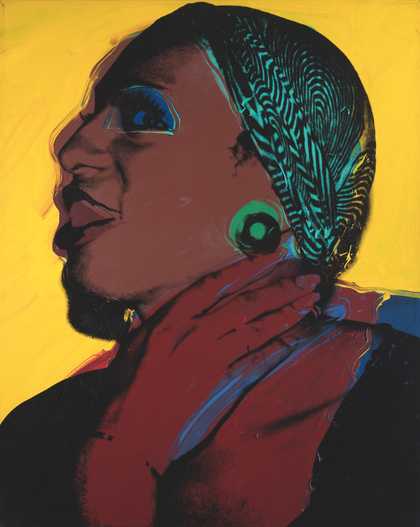

‘Was Andy Warhol Sexist?’ Revisionist readings and headlines generated by our present-day gender politics have dominated the most recent attempts to revise and re-evaluate the artist. Critics wondered if his society portraits – with their garish, painted maquillage and misogynist beauty standards – were reductive. Once again, writers opined that many of his female film subjects, most notably the tragic Edie Sedgwick, were exploited. And then there are the thorny issues around the trans women who have been ongoing subjects – from Warhol’s 1971 film Women in Revolt, which satirises feminist activism, with Holly Woodlawn, Candy Darling and Jackie Curtis playing the collective PIGs (Politically Involved Girls), to his controversial print series Ladies and Gentlemen 1975, depicting unnamed drag queens and trans women of colour. Fuelled by our ‘cancel culture’, it may be tempting for many to dismiss Warhol outright on the grounds of shifting social mores. While such posthumous accountability to contemporary politics is a vital part of the cultural debate, Warhol’s attitudes towards sexuality, gender expression and identity politics were rife with complexities and contradictions that we can delicately unpack with both the benefit of historical context and with deference to the sensitivities of today’s crucial debates on these issues.

On the flip side, recent scholarship has rigorously spotlighted Warhol’s queerness, labouring to foreground the homosociality of the Factory and the homoeroticism of his oeuvre – elements that mainstream art histories (and the conservative tastes of the art market) had previously squelched. While these queer histories are clearly valid and much-needed additions to Warhol scholarship, their readings often pay shorter shrift to a holistic vision of Warhol’s life / work complex that accounts for the manifold roles that women play both off, and on, the canvas and the screen.

Andy Warhol, Ladies and Gentlemen (Wilhelmina Ross) 1975, acrylic paint and silkscreen ink on canvas, 127 x 101.6 cm

© 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London

While he was no Judith Butler, Warhol had very early instigated his own kind of Gender Trouble (1990) that challenged rigid identity categories. As the opening epigraph from his book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975) suggests, the ‘Warholian project generally scrambled all available gender codes’ and subverted the male / female matrix well before there was the theoretical language or political will to do so. In other words, for Warhol, trans women were women, full stop. Though he expressed such ideas without recourse to our correct feminist and queer terminology, this expansive view of gender is key to understanding the agency of women within the Warholian project. When Warhol was filmed lying in bed talking to David Bailey as part of his incredible 1973 documentary Warhol, they make this inclusivity crystal clear:

Bailey: You attract a lot of those people in the studio and doing those films, no? Not closet queens, drag queens?

Warhol: The people we use aren’t really drag queens, because drags queens are people who just dress up for like eight hours a day. The people we use are people who think they’re really girls, and I think that’s so different.

Warhol’s trans-inclusivity is an important part of a larger story around the gender politics of Andy’s chosen family and oeuvre – the icons and celebs alongside the 1950s fashion editors, gallerists, queens, confidantes, and behind-the-scenes faithful collaborators. It becomes clear that, in his own subversive way, Warhol was an equal-opportunity Andy.

Madam Warhol

Endlessly mythologised, Andy Warhol’s Factory was a queer beehive of art and life that ran from 1962 to 1984, first in a vast loft on East 47th Street, moving to Union Square in 1968, then again in 1973 to 860 Broadway. At first, this was the temple of Warhol’s high-pop painting period; the site of production for his early masterpieces that, more often than not, immortalised famous women. But the story only begins with the canvases that enshrined Andy’s holy trinity of 20th-century American glamour: Marilyn, Jackie and Liz. His preoccupation with famous female icons is well documented in this period, but Warhol’s women are at their most complex and subversive off the canvas.

Andy Warhol with (foreground, from left) Brigid Polk, Candy Darling and Ultra Violet at the Factory, New York City, 24 April 1969, photographed by Cecil Beaton

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s

Exactly half of Warhol’s homegrown pantheon of Factory ‘Superstars’ were women. They included Pat Ast, Benedetta Barzini, Susan Bottomly (aka International Velvet), Jayne County, Jackie Curtis, Candy Darling, Isabelle Collin Dufresne (aka Ultra Violet), Andrea Feldman, Jane Forth, Cyrinda Foxe, Bibbe Hansen, Jane Holzer, Sally Kirkland, Ivy Nicholson, Naomi Levine, Elecktrah Lobel, Mario / Maria Montez, Nico, Brigid Polk, Edie Sedgwick, Ingrid Superstar, Cherry Vanilla, Viva, Holly Woodlawn and Mary Woronov.

‘The superstar was a kind of early form of women’s liberation,’ recalls Factory regular Danny Fields. ‘They were so smart, beautiful, aristocratic, and independent. They were like Garbo and Bette Davis in that system of the Thirties. They were indulged by everyone. They were as smart as any of the men around. Everybody, from little boys to old faggots, fell in love with them.’

The terminology (and stigma) of sex work has long circulated in critical discussions of the Factory – both in its early so-called ‘prelapsarian’ and late ‘worst of Warhol’ phases. In the 1980s, Warhol was often accused of ‘whoring about’ as well as ‘starfucking’. With both men and women, Warhol embraced transactional economies in business and personal realms.

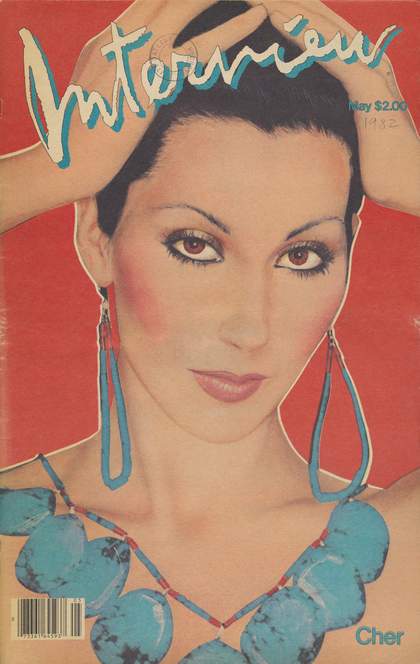

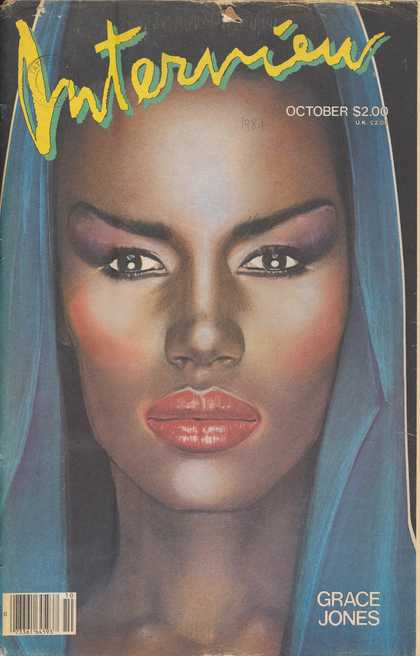

Cover of Andy Warhol's Interview magazine from May 1982, featuring Cher

Cover of Andy Warhol's Interview magazine from October 1984, featuring Grace Jones

Writing in 1971, critic Barbara Rose evoked the figure of the prostitute, fusing it with a reference to Warhol’s Catholic roots, writing: ‘It is possible future ages will see Andy in the image of Mary Magdalene; the holy whore of art history who sold himself, passively accepting the attention of an exploitative public which buys the artist rather than his art … a kind of Mary Magdalene “giving it away”.’

Queer theorist Jennifer Doyle observes: ‘Whores, hustlers, madams and drag queens are popular among Warhol critics as figures for Pop’s perversions – for how Pop flaunts the business of art.’ Doyle cites art historian Thierry de Duve’s disparaging assessment of Warhol’s Factory model: ‘Warhol was like a madam because he was “content to base his art on the universal law of exchange” and to “make himself the go-between for the least avowable desires of his contemporaries, each with his or her own ‘look,’ quirks, neurosis, sexual specificity, and idiom”.’

In this derogatory judgement of sex work, critics like de Duve would position his Factory as a “brothel” of gorgeous superstars that Madam Warhol manipulated. His book Popism (1980) and his Diaries (1989) capture his stoking of jealousies, his fuelling of rivalries and enabling of sexual exhibitionism – all captured by his voracious camera and tape recorders. In de Duve’s rather sexist estimation, this prostitution metaphor is purely pejorative: it ignores the possibility of interpreting sex work as a legitimate form of labour when it is consensual and fairly compensated.

A radical branch of feminism argues that the stigma of sex work is an extension of patriarchal subjugation of women’s bodies as well as their economic and sexual autonomy. In 1973, Margo St James founded COYOTE (Call off Your Old Tired Ethics), an alliance of prostitutes and feminist activists. St James proclaimed that ‘there is no immorality in prostitution. The immorality is the arrest of women as a class for a service that’s demanded of them by society.’

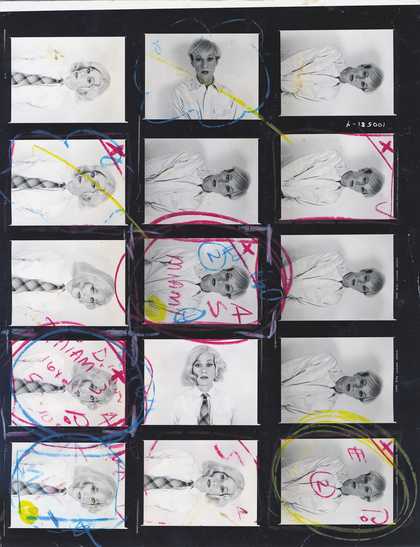

Contact sheet of photographs of Andy Warhol in drag, photographed by Christopher Makos

© Christopher Makos

Considered in this radical feminist light, the metaphor of ‘Madam Warhol’ emerges as an empowering and ethical figure. Madam Warhol – subconsciously evoked in Christopher Makos’s portraits of Andy in drag from the early 1980s – engendered a relatively safe, mutually beneficial space for his female and male collaborators. It was one built on transactional exchanges and consent – both during the early bohemian goings-on of the Silver Factory as well as in the late Business Art period. If, in 2020, we are comforted by the fragile humility of that Andy who, in the early 1960s went to church and adored his immigrant mother, we can also find vital empowerment in this incarnation of Madam Warhol who, like a contemporary Kardashian ‘momager’, harnesses and shamelessly deploys the power of sex work in order to protect and provide for her big queer family. As these possible retellings of the Andy Warhol story reveal, we have never needed Andy more than we do today.

Andy Warhol is on at Tate Modern, 12 March – 6 September.

Alison M Gingeras is a curator and writer based in New York and Warsaw.